Motor training

Motor training in this chapter includes ‘hands-on’ treatment procedures called physiotherapy suggestions and therapeutic activities by anyone daily involved with a person with cerebral palsy, called management, or treatment and management. The therapist needs to select and supervise methods for others assisting a person, according to what is relevant to their situation and skills. As discussed in Chapter 2, a therapist clarifies what a child and parent or carer want to achieve, what are the joint therapy aims and methods, with joint evaluation of which methods are appropriate. Selection of aims and methods by a therapist is based on the assessment framework discussed in Chapter 8.

Aims and methods are for the following interrelated aspects:

The direct training of developmental motor functions often simultaneously minimises the constraints by impairments. It is the appropriate selection of methods for direct training of active motor function with its components that can increase strength, improve joint ranges, decrease stiffness of hyper-tonus, modify hypotonus, reduce residual infantile responses and some involuntary movements. As motor training increases a child’s repertoire of movements and postures, there is less need to use abnormal performances.

Therefore, the emphasis on motor function and simultaneous improvement of performance in this chapter does not separate treatments of impairments from training of function. They can be integrated. However, this does not imply the disappearance of the cerebral palsies but rather an improvement of function as much as is possible for each child.

Chapter 11 on deformities suggests treatments of specific impairments which are not adequately modified by functional methods. This is particularly needed in severe conditions when active function is very poor or absent. There are also treatments of secondary impairments.

Motor training in daily life activities

Although this chapter concentrates on the motor problems and locomotion for daily life, there are also preparation for other activities in a child and older person’s lifestyle. In Chapters 2, 10 and 12, motor training is more explicitly presented as part of training daily life activities. Chapter 10 further summarises the motor functions trained in this chapter in the context of feeding, dressing, washing, toileting and playing. Reviews are given of motor function and perception and motor function in communication, speech and language. Occupational and speech and language therapists specialise in these aspects, and collaboration with them is essential.

Learning motor function only in these whole daily life activities and contexts can be too complex. Motor function needs to receive specific concentration on the deficient motor apparatus. Similarly, perceptual problems, speech and language difficulties and special problems of hearing and severe visual impairment need to have structured separate sessions of specialised treatment and teaching. However, as Neistadt (1994) points out, the specialised training of perceptual problems does not transfer to other contexts. Like motor training, they apparently need to be trained in different contexts as well.

Thus, therapy and management have four main related procedures:

Developmental levels and techniques

The therapist will use the developmental channel most appropriate to the posture in which a child might manage to carry out the chosen daily activity. This might be standing for transfers, sitting for eating and socialising or lying for bed mobility and getting out of bed. The therapist’s assessment of the developmental stages of a child’s postures reveals which each child can use independently or with appropriate support.

The following are important points for the developmental motor training:

General plan of the developmental programme

Initially therapy plans start with the developmental sequences in prone, supine, sitting, standing and hand function as guidelines. Typical components of functions and whole functions are developed in these sequences. As a therapist gets to know each child, modifications may or may not be needed. With experience of a child’s needs, together with careful observation of each individual, modifications become obvious. The developmental sequences are therefore flexible and not a dogmatic scheme.

Using the assessment findings of what individual children can and cannot do, plan a programme to:

Establish motor functions already achieved, so giving a person confidence that there is something he can do. Build on these motor functions in the next developmental levels.

Establish motor functions already achieved, so giving a person confidence that there is something he can do. Build on these motor functions in the next developmental levels. Attempt motor functions at the next developmental levels not just current level of child. This is to check any flickers of response to assess readiness of a child to try a more advanced motor item(s). Parents are encouraged to report when their child seems ready for a more advanced developmental motor function. These are also called ‘transition stages’ and thought to be the times when intervention is most beneficial (Bodkin et al. 2003).

Attempt motor functions at the next developmental levels not just current level of child. This is to check any flickers of response to assess readiness of a child to try a more advanced motor item(s). Parents are encouraged to report when their child seems ready for a more advanced developmental motor function. These are also called ‘transition stages’ and thought to be the times when intervention is most beneficial (Bodkin et al. 2003). Consider any developmental omissions/gaps as possible contributions to compensations, resulting in abnormal performance. Omissions are not always important owing to individual variations.

Consider any developmental omissions/gaps as possible contributions to compensations, resulting in abnormal performance. Omissions are not always important owing to individual variations.Age of child and techniques

Select techniques according to a child’s next developmental level and not according to chronological age. Use a similar approach when treating deformity. For example, asymmetry or persistence of prone flexion is normal for a child developmentally delayed to levels 0–3 months. Select methods for 3–6 months. Commence functional training of feeding, dressing, washing for a baby and for a severely and profoundly affected child, adolescent or adult using whatever developmental prerequisites of sensation, understanding or motor abilities that an individual may have, no matter how minimal (see Chapter 10). Communication to babies, children and older persons with learning disabilities have to be given according to their level of understanding (see section ‘Motor function and communication, speech and language’ in Chapter 10).

It is unfortunate that some workers still think physiotherapy should be cut down in older children and more time given to education as motor progress is no longer expected by them. In some individuals, motor controls may only mature much later and unless stimulated will remain dormant. There is controversy and different views on the need for training walking (see subsection ‘Prognosis for walking’ in this chapter).

Different environments. For any age group, an individual’s teachers and other personnel in their life need to be shown how to include motor activities so that precious school time is not lost from their education. The physiotherapist at the child’s school can work out ideas with teachers and classroom assistants for motor activities appropriate for classroom, playground or in physical education. At all ages, school children and older people with cerebral palsy need to be kept as physically fit as possible. Extra effort also needs to be made by a therapist to maintain contact with a school child’s or adolescent’s parents (see Chapter 7 for adolescents and adults).

Onset and techniques

Response to therapy sometimes seems much quicker if the onset is sudden on a previously normal nervous system. However, ultimately spontaneous recovery and motor development in acquired brain lesions may be as unpredictable as in babies born with apparent brain damage. Children with either congenital or acquired lesions warrant appropriate therapeutic procedures given in this book so that the potential of any of their nervous systems is given every chance to reveal itself. There are more behavioural problems in many children following a traumatic brain injury, which may interfere with therapy. Psychologists need to be consulted for advice concerning these problems. Expectations of better results in children who have ‘already known normal movements’ may be more of a frustration than a help. It is not so much the memory and experience that matters but the amount of damage and the capacity of any particular damaged system to compensate for the abnormalities.

Diagnosis and techniques

The techniques are not devised for particular diagnostic types but for motor problems of developmental delay and abnormal performance. Different diagnostic types of cerebral palsies may have similar functional levels and some similar abnormal performances described in this chapter. Other diagnostic conditions causing only motor delay may exhibit abnormal performance also seen in cerebral palsy, for example rounded backs, hyperextended knees or pronated feet. This is especially so if abnormal performance is a compensation for delayed balance (postural mechanisms).

Application of techniques

These should be carried out by qualified paediatric physiotherapists and occupational therapists and for daily management jointly selected with anyone caring for the child or with an older person with motor dysfunction. Selection depends on an individual’s abilities, time and changing family situations.

Repertoire of techniques in this book cannot possibly include all those available. Firstly, not all individual problems and different situations could be included together with possible techniques. Secondly, it is difficult to describe techniques without demonstration and only those techniques which could be described have been included. Thirdly, those techniques which have been frequently used have been selected. There are many more. Techniques in this book are thus suggestions not recipes.

Lack of response to any technique given in this book indicates the need to try others in this book or in other publications or preferably from clinical colleagues. Check that if the child scarcely responds to any technique, it is not due to:

As visual impairment has a significant impact on motor function, this is now discussed in more detail.

Motor development and the child with severe visual impairment

Motor delay will occur because of the visual impairment in otherwise normal children. When cerebral palsy is also present, the delay will be augmented. Intellectual disability may be present or only appear to be present as the child is limited by the multiple disabilities. The therapist should learn what influence the visual problems have on motor development as they do not only delay but also create unusual patterns and sequences of motor milestones. Abnormal movements or blindisms such as hand flapping, waving over light sources, eye poking, rocking and other bizarre patterns are seen in children, especially in some of the children referred late for training and parental advice. These will need special methods advised by psychologists, paediatricians or specialist teachers for children with visually impairment.

The methods for motor developmental training in this book can be adapted for children with severe visual impairment provided that the following factors are kept in mind.

Hypotonia, motor development and the postural mechanisms

As discussed throughout the book the postural mechanisms are undeveloped in children who are hypotonic (see the subsection ‘Postural mechanisms’ in Chapter 1 and the subsection ‘Hypotonicity’ in Chapter 11). Blind as well as sighted children who are immobile may be hypotonic. Jan et al. (1977) discuss floppiness or hypotonia associated with lack of movement in blind babies. Assessment and development of the postural mechanisms in the visually impaired baby and young child have been studied by the author and found to be delayed. As vision is an important factor in detecting the vertical in the child’s world and in appreciating any tilt of his world, it is not surprising that the blind baby’s postural control is absent or poor (Sonksen et al. 1984). Blind babies prefer to lie safely on the ground and avoid the challenges of gravity. The development of the postural mechanisms is the story of motor development against gravity and changes in gravity. Their absence inevitably delays this gross motor development. Motor development is discussed below. The visually impaired child, with or without cerebral palsy, will need careful assessment and training of the postural mechanisms using auditory, tactile and increased proprioceptive and vestibular stimuli.

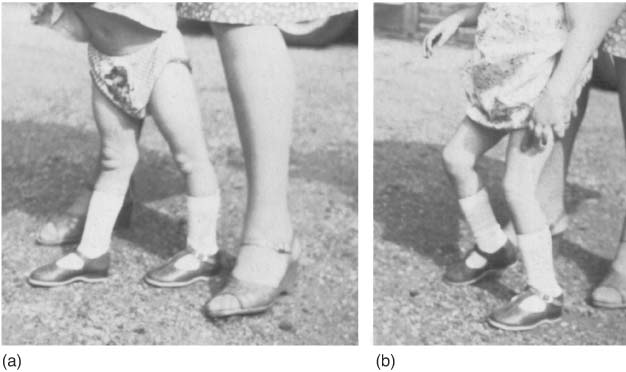

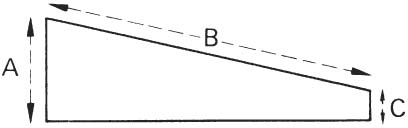

Postures such as rounded backs in sitting and standing, hyperextended knees and flat feet are common in young hypotonic children, particularly in visually impaired babies and children (Fig. 9.1). The specific delays in postural stability, counterpoising, forward tilt and posterior saving reactions are often observed to accompany the presence of round backs and shoulders (Levitt 1984).

Vision stimulates and monitors the postural mechanisms. Sugden (1992) reviews the various studies on this aspect. It is the exciting object or person that a typical baby catches sight of that provokes him to look up. This then stimulates the head righting and postural stability of the head. It is also the effort to understand the visual stimuli that further activates exploratory movements and increasing postural control whilst exploring. Methods to develop the postural mechanisms or the motor functions cannot be isolated from a child’s total development (Zinkin 1979; Sykanda & Levitt 1982; Levitt 1984, Chapter 14; Sonksen et al. 1984).

Total child development and motor training

Mother–child relationships. The shock and stress felt by the mother who does not even receive the primal gaze from her blind baby (Goldschmied 1975), as well as his unusual reactions to her feeding and cooing, must be understood by any therapist attempting to help. All motor developmental training needs to be designed to build up mother’s and father’s confidence in parenting their child. Many of the gross motor activities in play help enormously in creating bonds with the child. The techniques in this book should all be adapted to take place on mother’s lap, close to her body and face so that her kisses, touch and stroking and talking to the baby not only help motor development but also body image, movement enjoyment by the baby and demonstrate to the baby love and security which he needs so much. Clinging to mother in an unknown or puzzling world should be allowed for longer than in sighted babies and children. The weaning of the child with visual disability to a physiotherapist needs to be carefully done after mother–child bonding and confidence is established. Introducing more than one therapist or developmental worker may be disconcerting to the child and even the parents. Other disciplines advise one therapist rather than all handle a child themselves. Such a child is particularly sensitive to touch and voice, and needs to be handled by a few familiar people until confidence is established. Family participation in helping and especially in enjoying the motor programme with a child who is visually impaired is planned by therapists. If mother is under stress, it is important not to overload her with exercises, but rather use corrective movements and postures within the daily living activities of the child. Social workers and other counsellors work closely with therapists to help the family (see Chapter 2).

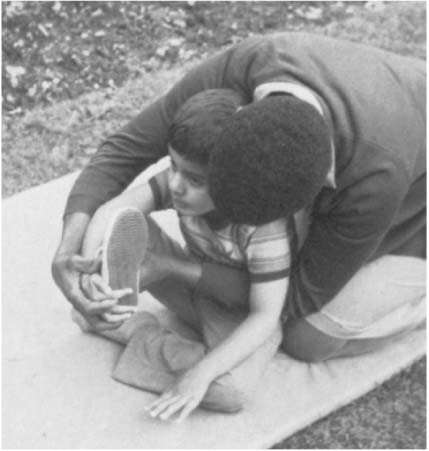

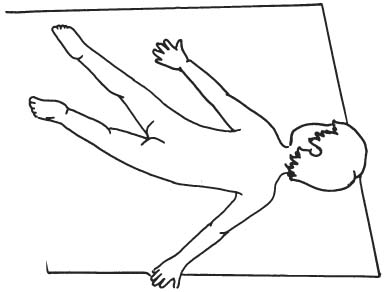

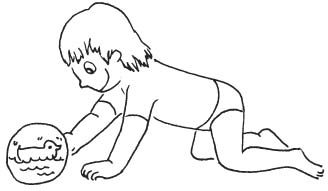

Motor function and the child’s daily life (Chapter 10) is usually the priority in the developmental motor training programme for a child with visual disability, not only from the parent’s viewpoint but also from the child’s viewpoint. The purpose of motor function needs to be emphasised when conveyed to each baby and child (Fig. 9.2). If not, he or she could be trained in basic motor patterns but never use them. He or she cannot see their purpose!

The assessments of the child’s developmental stages in feeding and other self-care, play or sen-sorimotor understanding and in exploration of the world must be obtained in order to introduce the corrective motor patterns appropriately. There are special stages and sequences for severe visual impairment (Reynell & Zinkin 1975; Kitzinger 1980).

Use of compensatory stimuli for motor development. As vision is not available, it seems obvious to use auditory and tactile stimuli to facilitate motor development. However, it is vision which normally teaches the baby what makes sounds, where they come from in direction and in distance, how humans communicate and the association of sounds with situations such as mealtimes, bath times and so on. Therefore, first train a baby what sounds mean before they can really motivate him to move. Also use existing movements to confirm what sounds mean.

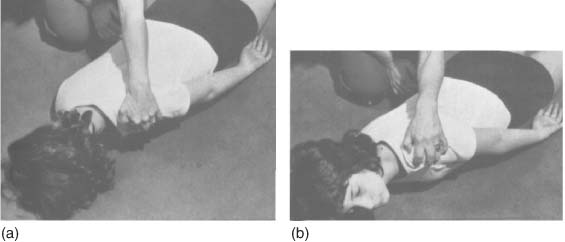

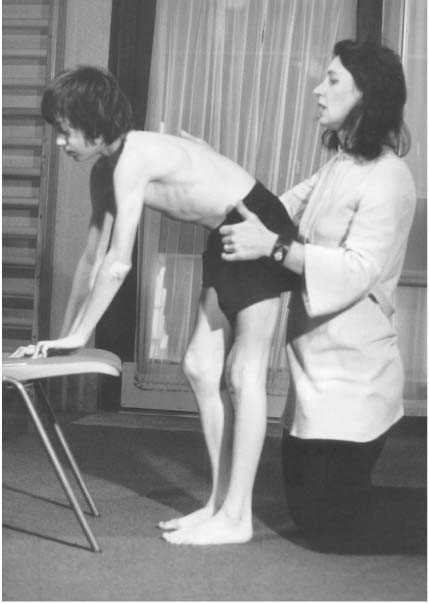

Figure 9.1 Hyperextended knees (a) being corrected (b) by training pelvic control (postural stability and counterpoising).

Figure 9.2 Movements for dressing.

Auditory development is followed as observed in the normal child (Sheridan 1975) but with special adaptations for the visual impairment (Sonksen 1979). First, the baby is trained to listen, then to turn to sound and after that to reach for sound. A very young child will first localise the source of sound near his or her ears horizontally and then above and below the head. Each child is helped kinaesthetically to search for the sound kept stationary nearby. Developmentally this will be at ear level, horizontally, above, below and then behind the child. The child will only achieve reach for sound when his conceptual development includes the permanence of objects and their sounds. It is at about these stages that reach and move towards a sound will only be worth using to stimulate roll over, creeping, crawling or bottom shuffling. Until the permanence of objects is conceptualised, help the child locate sound and move towards it by providing tactile and kinaesthetic stimuli. Reaching for an object making the sound is easier if a child’s hand moves along a surface on which the object is placed.

Similarly the appreciation of tactile stimuli, localising and searching for them, has to be developed. Linking tactile with sound stimuli is carried out.

Encouraging a child to create sound independently is also included as he bangs a mobile, rattle, tambourine or a surface with hands or feet. The motor programme cannot be planned without these aspects that are devised by teachers, psychologists or developmental paediatricians together with the therapist.

Mother’s voice and her touch rather than the therapist’s will be more successful in the early stages. Vibration, smell, taste and air currents can be introduced and associated with real objects, and situations link sound, touch, proprioception and vestibular stimuli. All these aspects are part of the child’s conceptual development (Sonksen et al. 1984).

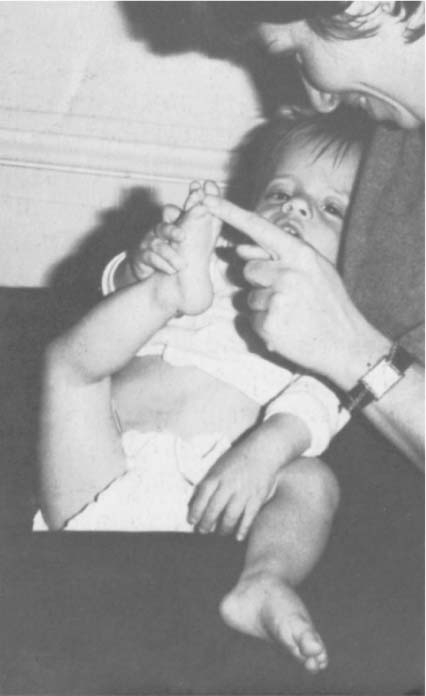

Body image development. Poor body image is related to poor motor experiences and not seeing body parts static or moving. Use of tactile stimuli on a baby’s body helps to develop the body image. However, it is the baby’s parent’s hands as well as the baby’s hands that are best to do the touching first. Hands of the baby are notoriously slow to move and explore because of many reasons, not least of which is the absence of hand regard. Help the baby bring his hands together in midline, pat-a-cake hand to hand, touch hand to mouth, to face hand to body and hand to feet (see Fig. 9.3). Later use as many other stimuli to his body such as rubbing with towels, soap, creams and powder at bath time. Use vibrating toys, bells and playthings placed for him to find on his tummy or limbs and invent similar ideas. The sections on stages of hand function development in this chapter and section ‘Motor function and perception’ in Chapter 10 offer ideas for the sighted child in this book. For the child without sight, these stimuli offered in play activities need to be emphasised and also presented more slowly and stage by stage. Do not bombard the baby with too many stimuli at once. Confusion or fear could be aroused if stimuli are not sensitively given. Thus, carefully introduce different surfaces for the child to roll on, creep, crawl and walk on with bare feet.

Always give a child time to experience tactile and auditory stimuli and allow the child to reach and find out about toys and objects with such stimuli and as independently as possible. Create opportunities for movement so that a child can feel his own body movements and how he actively produced them. If a child cannot or does not move alone, parents can move him and change positions for him. A child enjoys feeling his mother move about by being slung close to her body in a baby pack. Body image depends on proprioceptive and vestibular function.

Figure 9.3 Body image development.

Proprioceptive and vestibular function. These aspects are also part of total child development. They are compensatory stimuli for visual impairment and also develop body image. All the postural reactions are dependent on these stimuli in a developmental context discussed in this book. Touch, pressure and resistance can be correctly given to stimulate movement giving clues as to direction and degree of muscle action. Opportunities are also given for a child to lift, push and pull objects of different weights, which also increases proprioception and strength.

However, as with all therapy methods, give a child time and observe whether the child understands and is not confused by what is expected of him. Do not use therapy techniques with handling, pressures or other stimuli from behind him as he may well lean back or use his extensor thrusts to reach the stimuli or the familiar voice behind him!

Visual development. Not all blind babies are totally blind. Even reaction to light only can be used and perhaps developed to the child’s full, if limited, capacities. An assessment of the developmental use of residual vision is given by the developmental paediatrician and specialist teacher and relates to vision available for exploration and learning. This guides the therapist in her motor plan for the individual child. The therapist needs to learn how large an object can be seen by the child, how far away, whether it can be seen if stationary or moving and which visual fields are present. The therapist also needs to know whether there is equality of vision in each eye and the acuity as well as any other special visual defects which may affect a child’s motor development and use of therapy methods. The development of a child’s visual potential is easily integrated with the methods for head control, hand function and all balance and locomotor activities discussed in this book. The appropriate level of visual ability needs to be related to a child’s motor programme. There are times when one may have to accept unusual head position and other patterns which make it possible for the child to use residual vision. There may then be muscle tension or aches to be treated with exercises and massage.

Language development. It is important to talk and clearly label the body parts used and the motor activity if this does not distract a child’s attention on body image and motor training. A child may also not yet be able to understand words. Delay is normal for a child who cannot yet understand the meaning of sounds, words and conversation as he cannot see what they mean, cannot see gestures and cannot link the stimuli from the external world. Psychologists and teachers work closely with the therapists to plan the language and speech programme. This enables therapists to give general encouragement of language development and be advised on communication systems for a child and by a child with severe visual impairment.

Hand function development. The development of hand function is obviously the most important area for the child whose hands are his eyes on the world. The chapter on hand function in this book should be adapted to use compensatory tactile, auditory and proprioceptive stimuli before motor actions can be expected to follow the normal rate of development. Do not force objects into the child’s hand but train him to search for the nearby rattle, to orientate his hand to take it and to develop a variety of searching actions or finger moulding and feeling actions. Bilateral hand function will take more work than with a sighted child. Encourage both hands together in midline, holding and especially exploring both sides of a cup, bowl, ball or toy and transfer of toys. Train losing the toy and finding it. Offer toys which involve a child having to take them apart, and constructing them again. Also, find objects and toys which activate crude and fine voluntary grasp and release. Offer playthings which depend on hand and fingers pressing a switch to activate a sound, music or vibration or fan blowing air, the latter supervised by an adult.

All these actions do not only promote motor development but integrate with concepts of cause and effect, object permanence and other intellectual development of the child. Remember that index finger pointing and associated index/first finger grasp is very much a visual conceptual skill and will be delayed. Offer toys and food to promote finger actions as mentioned in the chapters on hand function, motor function and play, feeding and other self-care activities.

Gross motor development. Prone development is not popular with the baby with visual problems as there is no interest there, sounds cannot be heard as easily and he may be far removed from family and especially mother. There are no visual lures to provoke him to look up and progress to creeping and crawling. It is often noted that crawling is not used by blind children and that they prefer shuffling on their bottoms and then walking. It is, however, possible to train prone development on mother’s lap, on a soft cushion with attractive noises, especially that of mother’s or father’s voice with their gentle stroking of their child’s back. The advantages for a child having activities in prone are increased head and back muscle strength due to head and back extension. When a child pushes up on hands, this adds strengthening of shoulder girdles for arm and hand function. Balance on hands and knees leads to additional exploratory skills of crawling through space, feeling the ground and gaining additional body image experiences. The round backs and shoulders often seen in children with visual impairment benefit from stronger back extensors together with additional postural training in upright sitting and by using the arms to reach up for toys and especially to play with father or mother’s face and hair.

Crawling is not of course essential for the acquisition of walking, as bottom shufflers demonstrate. However, creeping, crawling, rolling or any mobility across space helps spatial learning and especially that the floor is continuous. This enables a child to be less afraid and be more motivated to walk alone. Walkers with wheels all around the child should be avoided as he will not develop his own postural and locomotive reactions. The child often sits or leans onto these walkers, stepping his legs but not learning to take weight through his legs and so learn to walk. Baby bouncers and rocking chairs are also undesirable if used for a long period when someone is not present. A child can withdraw into a rocking or bouncing world which engenders disinterest in the environment. Baby bouncers may provoke abnormal leg patterns, excessive ‘on toes’ postures (blindism) and increasing spastic shortening and dyskinetic patterns. Short supervised sessions in any equipment do often produce more desirable results, especially if parent–child interaction is happening.

Blind babies without other disabilities develop stationary postural control slightly later or within the ranges of sighted developmental levels (Fraiberg 1977). However, there is more of a delay of moving into, out of or forward from these postures. Thus, this book on developmental levels should be used as guidelines and neither as rigid rules for developmental ages nor as strict sequences for severe visual disability. The postural mechanisms of stabilisation, counterpoising, tilting and saving (protective) reactions and the methods given are in the sections on motor training of developmental functions below, but delays and modifications will be required according to a child’s particular vision and hearing development and his or her emotional and social situation.

As fears are common, the techniques should be adapted to build confidence and provide fun and a sense of adventure. Large balls, rolls and swings should only be used after confidence has been established in relation to the levels of development of the postural mechanisms present or just commencing in the individual child. Rising reactions will require extra care as all workers in this field demonstrate how much visual lures promote posture changes. All other motor developmental training from 0 to 5 years presented in this book should be offered and learned by a child to decrease the frequent clumsiness associated with visual impairment. Coordination exercises, balance tasks, music and movement, dance, games and physical education are of great value to children with visual disabilities. The older child will also be receiving mobility training from those employed for this work by the Royal National Institute of the Blind (United Kingdom). Teachers for severe visual impairment will integrate their work on this and other aspects with the therapists, as there is a need to create a whole programme for each child and family.

Prone development

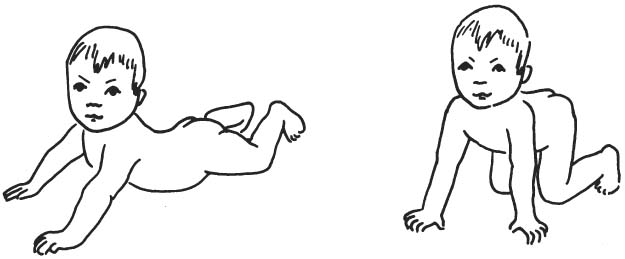

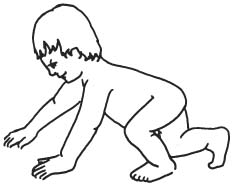

The following main features need to be developed at the individual’s developmental stages:

Postural stability of the head (Fig. 9.4a–d) when lying prone (0–3 months), on forearms (3–5 months), on hands (4–6 months), on hands and knees (6–9 months), in half-kneeling hand support (9–11 months) or on hands and feet (12 months). Head held in alignment with spine (4 months), with chin well in (5–6 months).

Postural stability of the trunk. At first a baby in prone is often in flexion with hips off the surface and then tips over into side lying with weight bearing continuing forward on cheek or side of face and shoulders (0–3 months). Weight then shifts towards the legs. As head, shoulder and trunk stability develops the child can control side lying and symmetrical prone lying (6–9 months). The back becomes straight and then slightly extended on forearms (3–5 months) becoming fully extended on hands (6–7 months). In ‘pivot prone’ (5–10 months) the trunk stabilises well in extension. When a child is on forearms, he shifts his weight backwards and forwards and to each side (3–5 months) and similarly when on hands (6– 7 months). Weight shifts are later used if creeping along the floor. When on hands and knees, weight shifts continue with a straight back held against gravity and adjusting antero-posteriorly for rocking, then using this with lateral and diagonal shifts during crawling.

Postural stability of the shoulder girdle (Fig. 9.4a–d). When taking weight on forearms (3–5 months), on hands with elbows semi-flexed (4–6 months) and elbows straight (6–7 months), weight bear on hands and knees (6–9 months) and in prone lying with arms held stretched forward along the ground to hold a toy (5– 6 months) or later when holding an object in the air (6–7 months). There is ‘pivot prone’ (begins 5–6 months and established 8–10 months) with weight on abdomen and pelvis with extended trunk and legs in the air as well as with arms held abducted-extended in the air to stabilise shoulder girdle (‘high guard’ position). Shoulder girdle stability is promoted with trunk stability in extension. In other positions, stability develops further during half-kneeling or in upright kneeling, leaning on hands (9–12 months) and during grasping a support, within all prone developmental stages, especially around 9–12 months.

Postural stability of the pelvis (Fig. 9.4d) on knees with hips at right angles (4 months), on elbows and knees (4–6 months) and on hands and knees (6–9 months). Stability of pelvis and hips on the surface (6–9 months) enables on hands with straight elbows, stabilises in half-kneeling and upright kneeling with support (9–12 months) and without support (12–18 months).

Postural stability and counterpoising of limbs are closely related.

Counterpoising of the head takes place in activities which include head partial raise and turn (0–3 months) and head movements whilst holding the head up against gravity (3–5 months). Free head movements are counterpoised in prone-kneeling postures (6–12 months).

Figure 9.4(a) Postural stability of head and shoulder girdle (on forearms).

Figure 9.4(b) Postural stability of head and shoulder girdle.

Counterpoising the arm movements in prone abdomen on the ground, creeping actions (3– 5 months), when weight bearing on one forearm whilst reaching with the other (5–7 months) or leaning on a hand reaching with the other (7 months) (Fig. 9.4c). Reach in all directions increases counterpoising abilities. All reaching is preceded by weight shifts in all positions in base and then away from moving arm, later towards a reach well out of base. Arms are counterpoised in crawling (9–11 months) and on hands and feet (12 months).

Counterpoising leg movements takes place in prone lying during creeping actions (3–5 months), leg movement on knees with upper trunk and arms being supported (5–6 months), leg lift when on hands and knees (6–8 months). Weight shifts precede leg movement first within base laterally and in rocking forward and back, leading to counterpoising limbs for crawling. This is together with the counterpoising of arms in crawling (9– 11 months) and in bear-walk (12 months). Stand lean on hands on low table (modified bear-walk position), weight shift laterally develops to allow counterpoising of leg lifting and also prepares for cruising at low furniture. This overlaps into the development of cruising in standing at normally 9–12 months levels in this chapter.

Figure 9.4(c) Postural stability and counterpoising arm reach.

Figure 9.4(d) Postural stability on hands and on hands and knees.

Figure 9.5 Rising from prone.

Figure 9.6 Tilt reaction in prone.

Figure 9.7 Saving reactions in the arms.

See Stages in Prone Development in Figs 9.8–9.22.

Treatment and management at all developmental levels

Rolling and rising

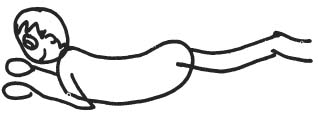

As rolling development takes place from supine to prone, prone to supine or a complete roll with side lying as an initial transition position, techniques are all outlined in the section ‘Supine development’ below.

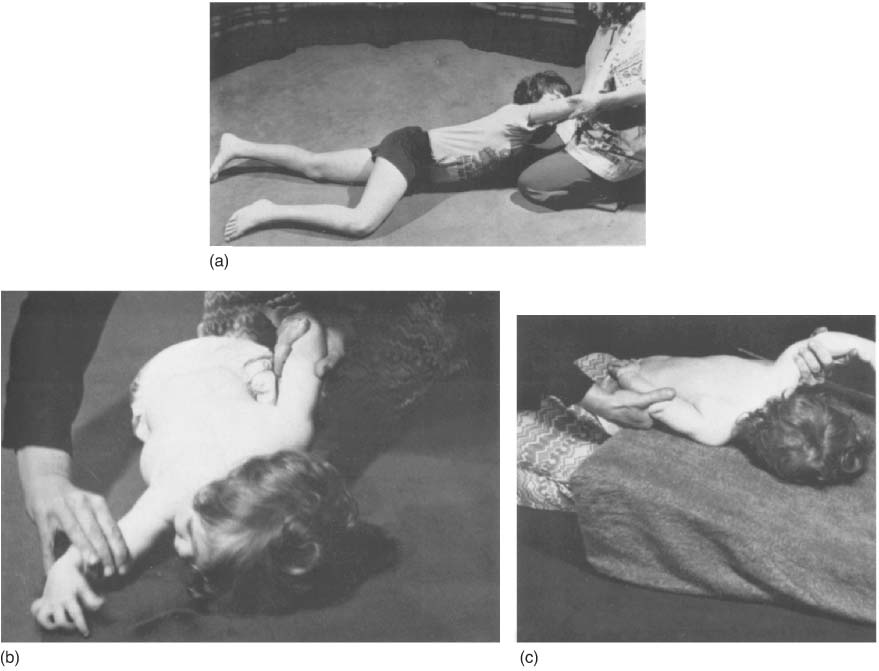

In this section, strategies are presented for rising directly from prone onto arms, onto knees, onto hands and knees and eventually into various sitting and standing postures in the prone developmental levels. The active and active-assisted sequences of rising strengthen muscles, stretch and increase ranges with a minimising of the tightness of hypertonic muscles.

0–3-month normal developmental level

Some common problems

Dislike of prone position. This may be due to early breathing difficulties, inability to turn the head and free the nose, inability to lift the head up, excessive flexion creating discomfort in prone, post-gastrostomy, severe visual impairment or even lack of opportunity given to lie on the stomach. Later a dislike of prone may be due to a child’s inability to use the hands in prone.

Delayed development of head control and on forearms (on elbows) posture. There may be no head raise or partial head lift and even no turn to free nose and mouth. Head turn is initially associated with body turn and later head turns keeping the body still. Head control may be poor when rising up on forearms and taking weight on forearms.

Abnormal performance (Fig. 9.23). Many of the motor patterns of a normal neonate and baby of 1–3 months may persist as abnormal performance in older children. This includes flexion posture or persistence of asymmetry in lying, with or without a Galant’s reflex on one side. There is abnormal asymmetrical head raise, rising on only one forearm, asymmetrical stabilisation on elbows. There may be more flexion–adduction in one leg than the other as the hips lift off the surface into flexion. Only one leg may flex and abduct into a forward creeping pattern with hips flexed or flat on the surface. Children with bilateral or hemiplegic impairment can begin to creep flexing the better or unaffected side whilst the other affected leg is less active in extension and internal rotation. This is seen especially when the child raises his head and turns to the less affected or unaffected side. Creeping pattern is limited without head control and use of arms.

There may be excessive flexion and adduction of both or either of the arms, with shoulder retraction, pelvis and hips in posterior flexion rather than lying flat. There may be flexion of the trunk or legs, or all of them. The head may be overextended with chin poking in lying and when raised. Extensor thrusts may persist. The child’s weight is taken onto his face, chest, knees and sometimes on feet when flexion is less. On head turning weight may not shift to the opposite side and body weight does not shift towards legs due to lack of head raise and flattening of pelvis. Weight shifts are needed for creeping along surface.

Figure 9.8 Flexion posture decreases. Head turn (0–3 months).

Figure 9.9 Head raise and hold (0–3 months).

Figure 9.10 Head raise, weight on forearms (0–3 months).

Figure 9.11 On forearms and/or weight bearing on knees (3–6 months).

Figure 9.13 Roll from prone to supine (3–6 months).

Figure 9.14 Weight bearing on hands (6–9 months).

Figure 9.15 Weight bearing on hands and knees (6–9 months).

Figure 9.16 Lean to one hand reach with the other (7 months).

Figure 9.17 Extend head, shoulders, hips pivot in prone position (8–10 months).

Figure 9.18 Hands and knees, lift arm, leg or both (8 months).

Figure 9.19 Crawling. Rise into crawl position (9–11 months).

Figure 9.20 Half-kneeling lean on hands (11 months).

Figure 9.21 Kneeling supported (11 months).

In hypotonia, particularly in very young children there is flexion–abduction of arms and legs with flattened pelvis into the frog position. In hypertonia, independent head raising in individual children may be associated with overflexion of stiff arms, stiffness of legs in extension–adduction–internal rotation. This persists into the next level when abduction and external rotation is normally expected.

Figure 9.22 Bear-walk (elephant walk) on hands and feet (12 months).

Treatment suggestions and management

Acceptance of prone position. Accustom the child to prone by placing him slowly on his stomach and on soft surfaces, such as sponge rubber, inflatable mattress, over large soft beach ball, over your lap (adding a cushion if your knees are bony!). Check that his nose is over the edge. Rock and sway him to a song.

Gently roll the child from side lying towards prone either on the soft surface or suspended in a blanket. Roll him back and forth slowly, keeping his nose free and observing whether he accepts going towards prone. Try using the incentives for head raise and turn, given below, to make prone lying more acceptable.

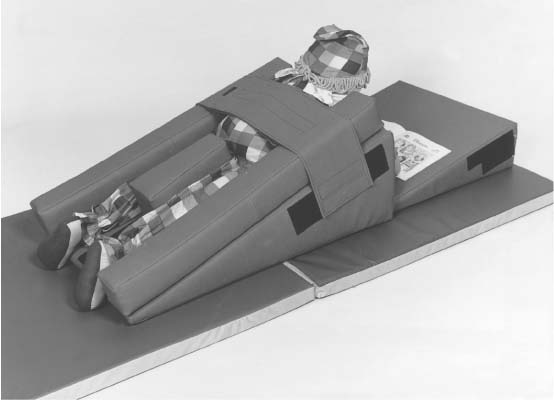

Severe conditions in older people. Prone is more acceptable in prone standers (Prone standing frames) in which the angle of the forward incline can be adjusted according to the person’s ability to just raise, hold or turn his head. The rest of the body is well supported by the frame so that head control can be trained. Interesting mobiles, television and social contact are among ideas to make this position worth doing by the person with cerebral palsy (see discussion on ‘Aims of standing equipment’ below). The aims are primarily for head control at this developmental stage

Figure 9.23 Some abnormal postures in prone.

Note: Some children continue to strongly refuse to go prone and should not be made to do so. They may be like those able-bodied children who are rollers or bottom shufflers and a few others who do not use prone development in their motor development (Robson 1970). Cultural influences may affect use of prone.

Head control. Train the following aspects of head control:

Raising the head (righting).

Raising the head (righting). Holding the head steady (postural stability).

Holding the head steady (postural stability). Turning the head from side to side (counterpoising the movement).

Turning the head from side to side (counterpoising the movement).Suggestions are as follows:

Figure 9.27 Head control and weight bearing on forearms (on elbows). Prone, on forearms over low wedge, roll cushions. Keep legs apart and turned out in those cases where legs press together and/or twist inwards. Use a pommel, toy, small wedge or cushion for legs.

Fgure 9.28 Wedge with lateral supports, adjustable strap to prevent twisting of trunk, sliding or rolling off wedge. Abduction block to separate adducted legs. (With permission from Jenx, Sheffield, UK.)

Figure 9.29(a) Child needing head, shoulder and trunk control.

Equal weight on forearms. Weight bearing is often better on one side.

Remember: Always try removing any supports given by your hands or equipment to check whether the child can lift the head or take weight on forearms on his own momentarily or reliably.

Physiotherapy suggestions

Abnormal postures. These are corrected within the treatment suggestions above. Physiotherapists select methods that parents or carers can manage and find relevant to their situation. Special methods and equipment for deformities may be needed (see Chapter 11).

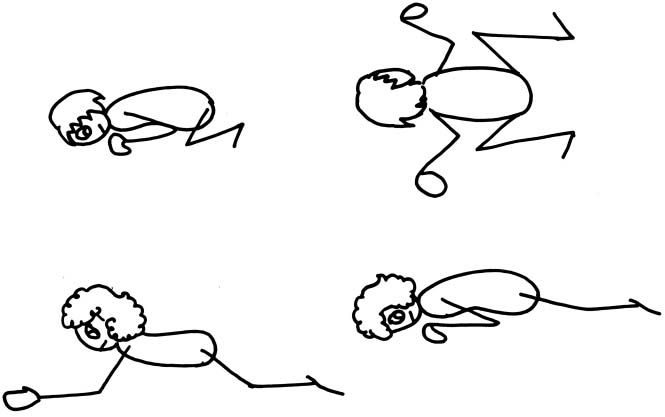

Creeping patterns. It is difficult to describe these patterns without demonstration. Some aspects will be described as these techniques are particularly helpful to decrease flexion in prone, for muscle strengthening, lengthening and for activating early creeping on abdomen. Babies or severely involved older children are most responsive and may use the automatic actions under their own control later.

The face arm is elevated into shoulder abduction–external rotation (Fig. 9.30b). The occiput arm is brought down into shoulder extension–adduction–internal rotation (Fig. 9.30c). The child may lie flat on the surface or over the edge of a roll, small pillow or wedge.

Modified creeping over mother’s lap or down a slippery wedge/incline is enjoyed by children. Once automatic creeping is experienced by a child, he needs to use it actively to reach an object or person he wishes to touch.

Train active rising on to both forearms or later hands at the same time. Hold the child’s head by spanning his occiput between his ears. Ask him to raise his head up against your manual pressure. This pressure and sometimes manual resistance facilitates rising on to his forearms or hands and teaches him to initiate rising with head action.

Augment head holding and forearm support by asking a child to maintain head posture as you gently push his head. Encourage child to pull his chin inwards getting a long neck. Also give manual nudge or push to front, side, back of shoulders, as child is told to ‘stay there’ or ‘don’t let me push you down’ or simply ‘hold it’.

Note: Use of resistance is particularly recommended for stabilising and strengthening the child with dyskinesia, ataxia and hypotonia. In all types of cerebral palsies, manual resistance needs to be appropriately given so that there is no abnormal overflow such as increase of involuntary movements, extensor or flexor spasms.

Figure 9.31 Rising onto knees and arms.

Figure 9.32 On hands and knees unsupported (6–9 months).

4–6-month normal developmental level

Common problems

Delay in acquisition of rising on knees, rising on to hands with extended trunk and flat pelvis. Weight bearing on knees, knees and forearms and on one forearm; reaching for objects; inability to lie prone with both or one of the arms stretched out to reach overhead; unable to roll over to supine or unable to creep on abdomen, on elbows or using a variety of creeping movements of both arms and legs.

Abnormal performance. Asymmetric, abnormal positions of limbs, clenching hands during the activities, beginning mermaid crawl (see 6–9-month level), asymmetric weight bearing.

Abnormal rising patterns in prone such as abnormal rolling patterns within rising. A child may use either excessive hyperextension of head and trunk, or flexing hips and knees under the abdomen on forearm support, then pushing up onto the hands or only rising onto the knees, leaving head, arms, hands and trunk fixed in flexion. Some children cannot use the arms at all or a child manages to push up on semi-flexed arms with hunched shoulders and then sits back on heels with legs bent inwards (W sitting).

Although useful for a child who has struggled to achieve these rising patterns, more mature and less effortful patterns can be trained.

Treatment suggestions and management

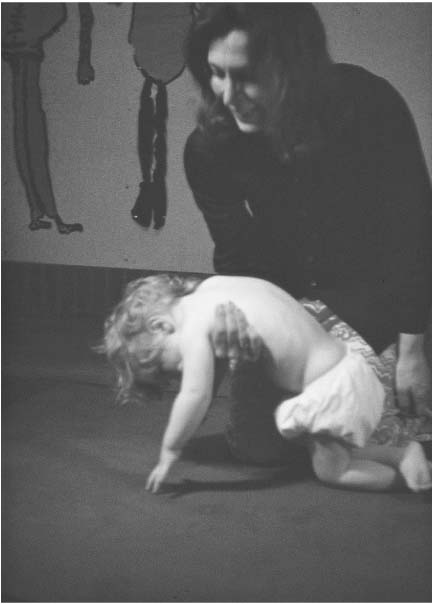

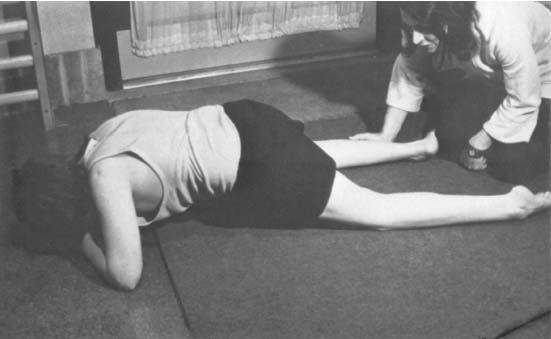

Rising on to knees, forearms and knees. Encourage the child’s rising onto knees instead of your lifting the child each time. Place one leg in creeping position and hold firmly or fix the foot against a heavy box, tip the child’s opposite hip and pelvis up and back with a slight touch and wait for active rise on to knees, first on to the one that is fixed. The other leg creeps forward on to its knee. Carry this out without giving the child a tip-up at his hip, if he can manage alone as shown in Fig. 9.31. Use instruction ‘Knee forward and get up!’ Rising onto forearms, and later, hands are usually activated as well.

Weight bearing on knees, on forearms and knees (4–6 months), on hands and knees, on hands with abdomen on the ground, or on hands over a wedge (6–9 months) (Fig. 9.32). Place the child on his knees, knees and forearms, hands and knees or on his hands with straight elbows with abdomen on the ground, according to what he can manage at his level of development.

Figure 9.33(a) Unstable shoulder and pelvic girdles with excessive action of elbow and knee flexors to maintain balance (postural control).

Figure 9.33(b) Training stability with weight shift of shoulder and pelvic girdles in four-point standing – a modification of developmental sequence.

Unstable weight bearing through the arms. Use joint compression through the top of the shoulder or the upper arm with straight elbow to develop stability on hands in prone, in sitting or standing positions (Fig. 9.33a,b). A low table is used for training arm-propping support. Keep the arms in straight alignment with the line of pressure through shoulder or elbow. Have a child’s weight through posterior ‘heels’ of the hands to avoid finger flexion. Arms are placed on a surface below the child, so the weight of his body adds to the joint compression, for example, a child may enjoy being held upside down for ‘standing or walking on hands’ with his elbow splints, for similar effects. Use a variety of floor textures to increase tactile experience.

Motor control actions for daily activities. These can also be learned in four-point standing and in prone stander with table.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree