Chapter 11 Treatment of Deep Osteochondritis Dissecans Lesions, Avascular Necrosis, and Osteochondral Defects of the Knee Using Autologous Bone Grafting

Osteochondritis dissecans

Osteochondritis dissecans (OCD) has undergone many treatment strategies, ranging from surgical excision as advocated more than 150 years ago1 to osteochondral autogenous grafting.2–4

The disease is rare in individuals younger than 10 years and in those older than 50 years.5 The male-to-female ratio has been reported as 2:16 or 3:1,7 with bilateral involvement in up to 33%.8 The medial femoral condyle is affected approximately 75% of the time (Linden, 1976 incidence study),5 with three fourths of the lesions affecting the lateral (intercondylar) portion of the medial femoral condyle. Kindreds with clear hereditary patterns have been documented,9 as has evidence suggesting no clear pattern of familial tendency.10

Many etiologies have been proposed, including repetitive microtrauma and impingement of the tibial spine,11 stress fractures with no identifying trauma,12 and vascular insult.13 However, vascular studies of the end the femur have demonstrated a rich vascular plexus to intramedullary cancellous bone, making this etiology unlikely.14 Histologic evaluation of specimens removed at surgery have demonstrated viable bone and cartilage and not empty lacunae.15

Classification and management

Categorization of the disease process into a juvenile or adult form is important at the time of diagnosis because the treatment and prognosis may be managed by different treatment algorithms depending on the stage of disease.16–18

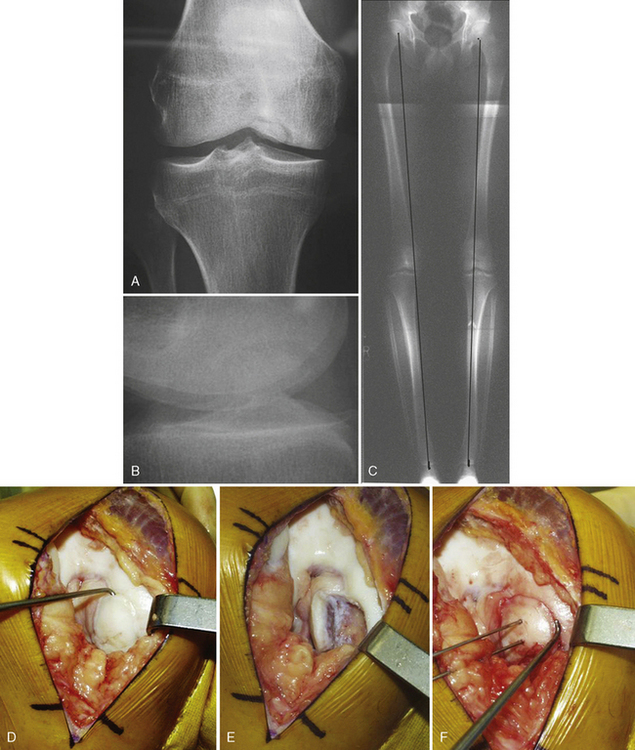

However, there is consistent agreement that knees treated by removal of OCD fragments that are detached from the weight-bearing femoral condyles do poorly.19–22 Linden23 noted that at average 33-year clinical and radiographic follow-up, 38 of 48 patients who had the initial manifestation after closure of the physes (i.e., adult form) had symptomatic and radiographic gonarthrosis. Linden23 stated that “Symptoms and roentgenographic gonarthrosis become more frequent and approach 100 per cent with time” (Figure 11–1).

Figure 11–1 A 44-year-old man with typical appearance of an osteochondritis dissecans lesion after the fragment had been removed. Universal progression to osteoarthritis was noted by Linden.23

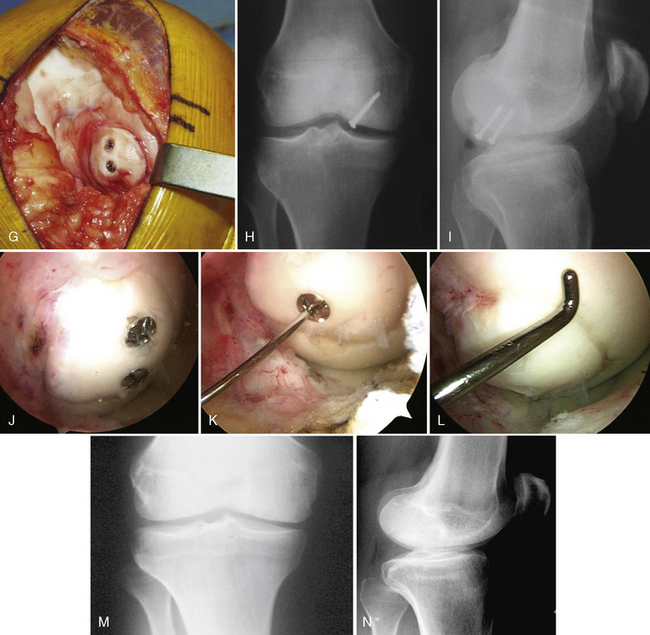

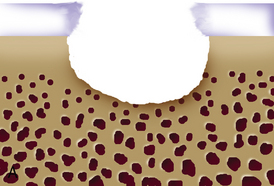

Cystic degeneration deep to the lesion in situ may occur, which makes bony healing especially difficult, even in the juvenile form (Figure 11–2).

Treatment by removal of the fragment and drilling to promote fibrocartilage repair is not recommended because the repair tissue is not durable and will break down.24–26

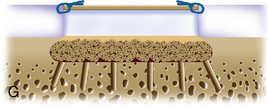

Optimal treatment is aimed at assessing the stability of the OCD fragment and obtaining union by casting immobilization in a stable juvenile fragment, or in situ flap, to fixation with or without autogenous bone grafting by open or arthroscopic technique. This is the treatment of choice for the adult form (Figure 11–3). An unstable OCD lesion is assessed for the underlying bony attachment by computed tomographic scan. Fixation to the underlying bony bed by standard AO principles of delayed union with curettage, autologous bone grafting, vascularization of the defect by drilling, and rigid internal fixation gives the best results.

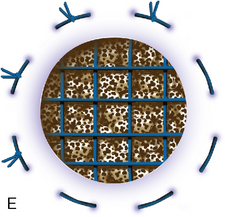

In cases of failed treatment of OCD with an empty defect or fragmented lesion, treatment options are ACI, autologous osteochondral grafting, or osteochondral allografting. ACI has the advantage of being autologous tissue in a young patient, with the potential to resurface large areas without donor site morbidity, as in osteochondral autograft transfers. Most defects can be managed by ACI alone when bone deficiency centrally is less than 6 to 8 mm deep (see Chapter 7).27

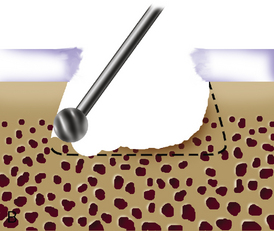

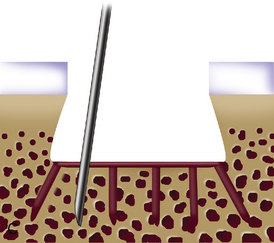

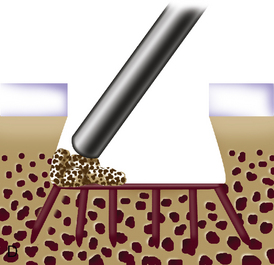

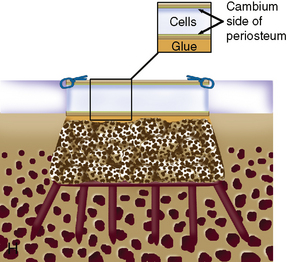

When cystic changes occur under the defect (see Figure 11–2), the defect has near-vertical walls and is greater than 8 to 10 mm deep, or the defect is very sclerotic due to a chronic lesion that may have undergone drilling, abrasion, or microfracture, it is safer to remove the unhealthy bed and bone graft the defect. The bone grafting technique is much like the preparation of a dental amalgam and is described in detail in Figure 11–4.