Chapter 17 Trauma Orthopaedics

Inpatients

• Trauma orthopaedics does not have to be complicated. There will be many different challenges that will not be encountered in other areas of physiotherapy.

• With a little preparation and knowledge about traumatic injuries and fixation, the management of patients in this setting becomes much easier and also much more enjoyable.

• Following the assessment set specific, measurable, appropriate, realistic and timely (SMART) goals and treatment plans in conjunction with the patient.

• From the first treatment session, the patient’s discharge should be planned.

• Where will they go after discharge?

• What assistance will they need?

• What follow-up will be required?

• The majority of patients require physiotherapy outpatient treatment, which may be in a trauma outpatients setting, in the patient’s home or in an outpatient department near to the patient’s home.

• Wherever they are treated, the physiotherapist will need a detailed referral including details of the injury, the operation, post operative instructions, past medical history, neurovascular status, previous and current range of movement (ROM) and power, previous and current mobility, physiotherapy treatment received, any complications of surgery or treatment, drug history at discharge and any follow-up dates to visit the surgeon. Most trauma wards have a template for this information.

• Understanding a patient’s injuries will influence the treatment plans and also the referral to outpatient physiotherapy.

Fractures

• Knowing how to describe a patient’s fracture can sometimes be complicated; however, breaking this down into sections will make it far simpler.

• The description of a fracture should enable any physiotherapist to have a good appreciation of a fracture without reference to an X-ray.

• The following questions will provide the information that will provide a clear description of any fracture.

Open and closed fractures

• If a fracture is exposed to the environment, then it is considered to be an open injury.

• This can be caused by the bone penetrating the skin from the inside or from something penetrating the skin from the outside.

• If the injury is not open to the environment, it is considered to be closed.

• Open fractures will obviously have wounds associated with them and also have a much higher risk of infection and this is crucial information for outpatient physiotherapists.

Types of fractures

• The type of fracture a patient has sustained will be a major determinant of the stability of the fracture, the subsequent treatment choice and weight bearing status (Table 17.1).

• The majority of fractures only contain two fragments and are classified as ‘simple’ fractures.

• If the bone has been fractured into more than two fragments, then it is classified as being ‘multi-fragmented’, also known as ‘comminuted’.

• In some cases it is beneficial to include the number of fragments, e.g. a proximal humerus fracture, can be written as a two-part fracture (simple surgical neck fracture); a three-part fracture (surgical neck and greater tuberosity fractures); or a four-part fracture (surgical neck, greater and lesser tuberosity fractures).

• It is important to know the different types of fractures and their subdivisions and worth having an orthopaedic textbook available to assist with this (McRae 2006). The main types of long bone fractures encountered will be simple transverse, oblique or spiral.

• Basically, a transverse fracture will be more stable than an oblique fracture, which is usually more stable than a spiral.

• In some cases, a transverse fracture will be stable enough to put weight through without causing any displacement.

| Type of fracture | Subdivisions |

|---|---|

| Simple | Transverse, oblique, spiral |

| Wedge | Bending, spiral |

| Multifragmented | Segmental, irregular |

The bones involved and location of the fracture

• Name the specific bone that was fractured.

• Describe whether left or right and where the fracture is on the bone.

• For long bone fractures, divide the bone into thirds – proximal, middle and distal.

• Name the section where the main part of the fracture occurs.

• If a fracture extends over two sections, this can be recorded as being at the junction, e.g. middle/distal.

• There are several bones throughout the body where it is more beneficial to describe specifically where the fracture occurred: e.g. ‘distal’ phalanx, ‘transverse process’ of the vertebra, ‘posterior’ rib, ‘neck’ of the talus; ‘distal pole’ of the scaphoid.

Angulation

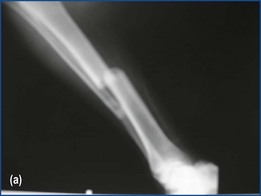

• Angulation occurs when the two main fragments of the fracture are still in alignment, but are at an angle to each other. This is quite common, e.g. radial fractures (Figure 17.1).

• The direction of angulation is described according to the direction the fracture site is pointing (consider the two fragments forming an arrow pointing in the direction of angulation), e.g. Colles fractures may have a ‘dorsal’ angulation.

Displacement

• Displacement occurs when the two main fragments of the fracture are no longer in alignment with each other.

• This can occur when the muscles pull the fragments in opposite directions.

• The displacement is described according to the direction of displacement of the distal fragment, e.g. medial or lateral; posterior or anterior; volar or dorsal; varus or valgus (Figure 17.2).

• The extent of the displacement is described by the approximate percentage that it is displaced (Figure 17.3a, b).

• Each bone will have its own classification systems, e.g. Schatzker classification system for tibial plateau fractures.

• These classification systems may not be known to the outpatient physiotherapist; therefore, although it is reasonable to include them in a referral, also include a full description of the fracture.

Principles of fracture fixation

• When a patient is admitted with a fracture, the surgeon will make a decision whether to treat them operatively or non-operatively.

• If they choose to fix the fracture, they will base the decision on four principles that will give a patient the best chance to return to their premorbid state (Table 17.2).

Table 17.2 Four principles used to choose method of fracture fixation

| 1. Stability | The type of fixation used will be based on the stability needed to allow the correct type of healing to occur (i.e. relative versus absolute stability) |

| 2. Preserve soft tissue | Soft tissue is essential in the healing process, so it is necessary to preserve this when inserting metal work |

| 3. Anatomical reduction and fixation | Anatomical reduction is needed to allow muscles and joints to function properly and unless alignment, length and rotation are correct, the patient will have irregular movement and gait |

| 4. Early ROM | The fracture should be stabilised sufficiently to allow early ROM, to encourage healing and prevent long-term stiffness |

Healing process

• The healing process of a bone begins the moment it is fractured.

• Depending on where a fracture is located and the surgeon’s choice of treatment, the bone will either heal by direct or secondary bone healing.

• The main difference between the two types of healing processes is that there is no callus formation with direct healing.

• Many patients ask about the healing process and the physiotherapist should familiarise themselves with both of these processes.

Factors affecting bone healing

• There are many factors that will influence fracture healing.

• These can be found in any orthopaedic textbook, but some of these factors are set out in Table 17.3.

• There are other factors that can affect bone healing such as steroid use, hormones, cancer and radiotherapy.

• The physiotherapist should be familiar with these and the background information relating to the factors in Table 17.3 as a patient’s surgeon will discuss many of these factors with them, but patients often ask their physiotherapist for clarification.

• Although not expected to be an expert on these factors, a physiotherapist should be able to encourage a patient to give themselves the best opportunity to recover as quickly as possible.

• Therefore, a little knowledge of each of these factors will help provide answers to a lot of a patient’s concerns.

• The patient will not be able to influence most of the factors listed in Table 17.3; however, there are a few specific points that require advice from a physiotherapist (Table 17.4).

Table 17.3 Factors influencing fracture healing

| Factor | How it affects bone healing |

|---|---|

| Age | In general, younger patients will heal quicker and have a greater ability to remodel than older patients |

| Smoking | There is a lot of research to suggest that people who smoke are more at risk of complications, e.g. delayed or non-union and increased healing times of the fracture and wound |

| Diet | Bone and soft tissue healing requires a large amount of calories, proteins and minerals |

| Systemic diseases | Diseases such as osteoporosis and diabetes will delay the healing process as they significantly reduce the number of proliferating cells |

| Degree of trauma | The more extensive the injury is, the more disrupted the surrounding soft tissue and the slower it will heal |

| Degree of immobilisation of the fracture | Fractures require some form of immobilisation to heal; therefore, if there is repeated disruption of the repairing tissue it will affect healing |

| Intra-articular fractures | Reasons for impairing healing include: Synovial fluid has collagenases which retard bone growth Joint movement can cause the fragments to move and hence, slow healing |

| Vascular injury | Bones need nutrients to heal and these nutrients are delivered to the bone via the blood supply from arteries, periosteal circulation and soft tissue If this is disrupted, bone healing is affected |

| Loss of bone apposition | Bone needs to be in relative contact to heal Therefore, if there is separation or interposition of soft tissue it will affect bone healing |

| Infection | Colonisation of bacteria can cause necrosis and oedema at the fracture site, which will slow and even stop bone healing |

Table 17.4 Specific factors that physiotherapists can advise patients about

| Factor | Advice |

|---|---|

| Smoking | |

| Diet | |

| Systemic disease | |

| Infection |

Types of fixation

• Once the surgeon has decided on the type of fixation as outlined in Table 17.4, they will choose the type of metalwork to achieve the best fixation.

• There are many types of fixations that will be encountered that are used with different types of fractures (Table 17.5).

Table 17.5 Types of metalwork, fixation types and fractures associated with these

The influence of fixation on the physiotherapy intervention

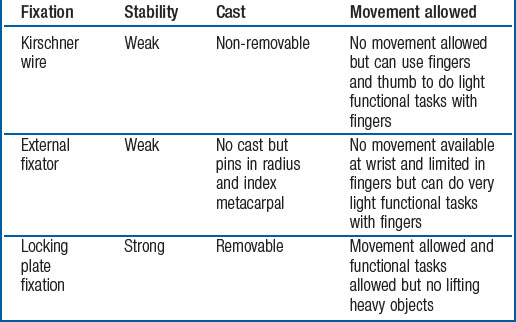

• The type of fixation that a patient has will inform whether or not the patient’s joint can be moved or they can weight bear on the operated limb.

• The same fracture can be fixed in different ways and this will influence the physiotherapy management (Table 17.6).

• In terms of weight bearing, metalwork that sits on the outside of the bone (plates, external fixators) tends to be a weight-sharing device, whilst metalwork that sits inside the bone (intramedullary nail) tends to be a weight-bearing device.

• Patients are more likely to be allowed to take some weight through their operated limb with an intramedullary nail than with a plate or external fixator (excluding Ilizarov frames).

• The surgeon should confirm this in their post operative instruction.

Other considerations

Pain

• Pain will play a major role in a patient’s rehabilitation following a traumatic injury and their subsequent management.

• How this is managed will shape the style and duration of the rehabilitation programme and subsequent discharge.

• If pain is poorly controlled, patients will refuse to be treated or only allow minimal input.

• Too much pain relief leads to drowsiness, nausea, faintness and even a loss of function.

• Either way will lead to a suboptimal rehabilitation programme meaning a delayed discharge.

• A physiotherapist will not be expected to set up a pain relief regimen, but will be expected to know when a patient needs more or less pain relief.

• Most trauma centres have pain specialists or acute pain teams that may need to be involved with individual patients.

• Patients may need background pain relief, e.g. paracetamol, codeine or tramadol to help with the pain caused by the injury or surgery.

• For more severe pain, they may need fast-acting pain relief such as Oramorph.

• Patient-controlled anaesthesia (PCA) and patient-controlled epidural anaesthesia (PCEA) machines may be another option that patients can use to gain adequate pain relief.

• Rehabilitation may cause increased pain; therefore, it is often prudent to ensure patients have extra pain relief prior to a treatment session.

Neurological issues

• Patients may have incurred associated injuries to the spinal cord, peripheral nerves or a head injury.

• Temporary or permanent neurological damage is often encountered in patients following involvement in a high-energy accident.

• Recovery time can be very slow, taking many months to show tangible signs of improvement.

• Neural integrity and extent of damage is determined in a number of ways, from magnetic resonance imaging to direct vision during surgery.

• Most surgeons will adopt a ‘wait and see’ approach if neural damage is considered temporary or occasionally patients may undergo nerve conduction studies to provide information about neural status.

• If neural function is altered, it is the responsibility of the physiotherapist to ensure it does not lead to complications, such as muscle shortening.

• Patients in bed for long periods require correct positioning to avoid muscle shortening and long-term complications (Table 17.7).

• Early intervention prevents more debilitating problems in the future.

• Casts or splints can be useful in these circumstances which should be ordered via plaster room technicians or occupational therapists as soon as possible.

• If sensation is affected, monitor their skin condition whilst using these.

• Educate a patient and their family about the possible complications and encourage them to be actively involved in preventing them.

• Teaching regular passive stretches and providing equipment to assist this is crucial, e.g. a bandage to self stretch ankle dorsiflexion.

• Lower limb neurological deficits can be helped by orthoses, e.g. a ‘foot up’ splint will assist a patient achieve a better ‘heel-toe’ gait pattern, by maintaining dorsiflexion during the ‘swing through’ phase.

• Despite orthoses, patients need educating about correct gait patterns, ensuring they comply with their weight-bearing status.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree