and François Moutet2

(1)

Marseille, France

(2)

Grenoble, France

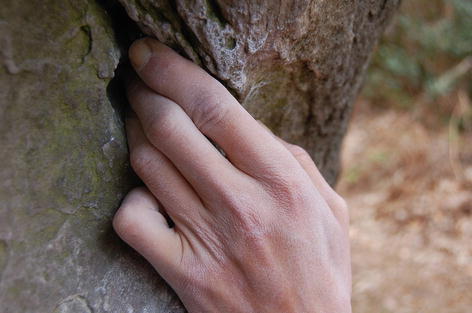

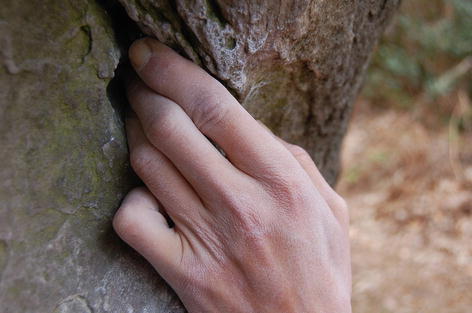

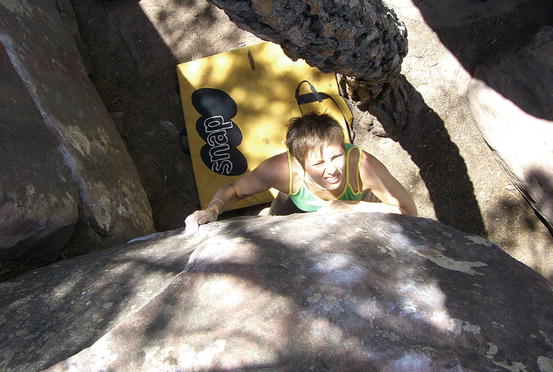

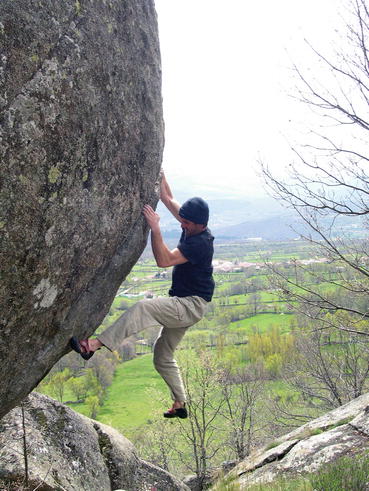

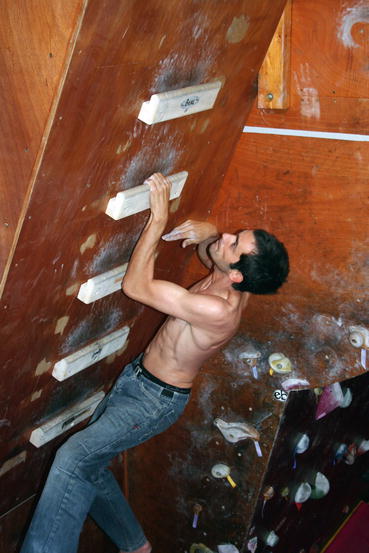

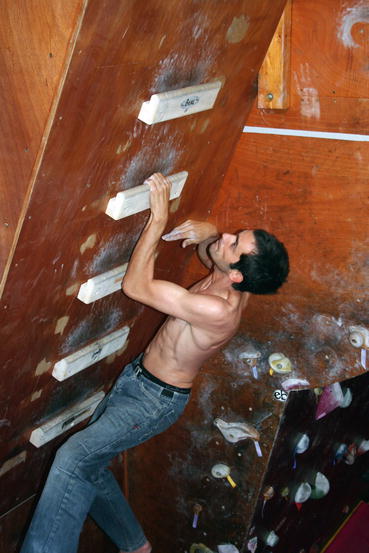

Photo 5.1

5.1 Climbing Different Grips

5.1.1 Strains of the Various Grips

The position of a finger can be either straight, arched, or hooked. The hand morphology, the various grips available outdoors or indoors (CG), the climber’s level, and his personal abilities are factors which determine the possibilities of seizing a hold.

The fresh climber prefers using the crimp grip. A maximum strength is liberated while gripping, and in a way, this fact reassures the athlete – emotional pole. As he gets more experience, learning new movements, his former crimp grip posture turns gradually into the open hand one. These various changes depend on his physical and emotional skills but also on his own sensations. It is important to develop all the possible tactics by training on various supports – different degrees of steepness, orientations, sizes, spaces, numbers of holds – especially outdoors in order to face any situations.

Reducing the seizing of holds to one posture – crimp grip or open hand grip – would be like decreasing the numerous possibilities available in rock climbing. In addition to finger locks and fist jams, some holds can be tackled combining the crimp and open hand grip using all the fingers in turn. These grips are essentially present outdoors, but some factors make them compulsory in CG. The steepness of a hold can require what will be called a mixed posture, that is to say, a crimp grip for some fingers and an open hand posture for others. A more developed musculature is consequently required between the deep finger flexors (DCF) and the superficial finger flexors (SCF). The finger common extensors (FCE) play a main part (cf. ch. Assessment and Safety). And later in the book, it will be demonstrated how important it is to reinforce them, to improve the stability of the joint system, and to support the strain endured, especially in the open hand posture.

To conclude, it is rare to find a hold perfectly linear as regards grips, especially in natural sites. The angles, width, depth, and steepness of the hold are various factors which give a vast number of actions to each finger. Therefore, according to these factors, the surface in contact or the necessary strength will change.

Hand morphology is also an important matter. Bearing in mind the differences between the four fingers and comparing the climbers’ hands, it becomes quite understandable why some of them can’t always use the open hand posture or the crimping one.

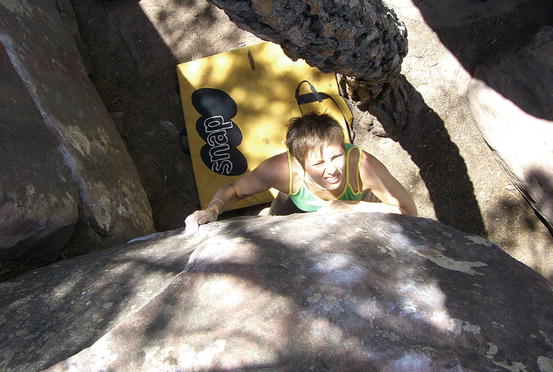

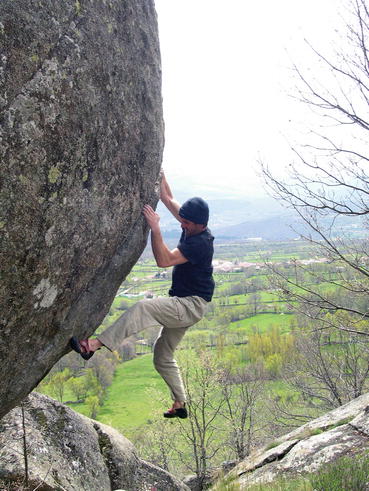

Photo 5.2

Fingers’ action and position influencing factors

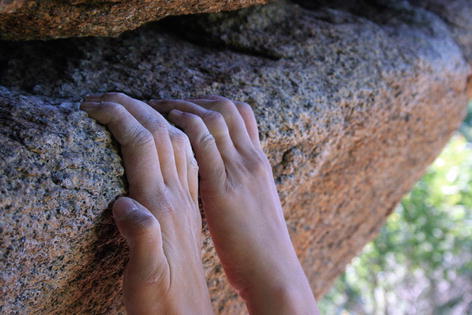

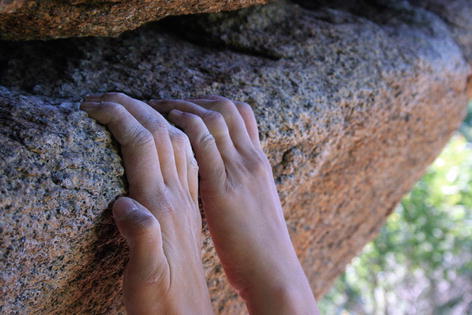

5.1.1.1 Open Hand Posture

This posture is not natural for a fresh climber. Indeed, the idea of “seizing the hold” refers to the image of “clinging to something” which is implied in the crimp grip.

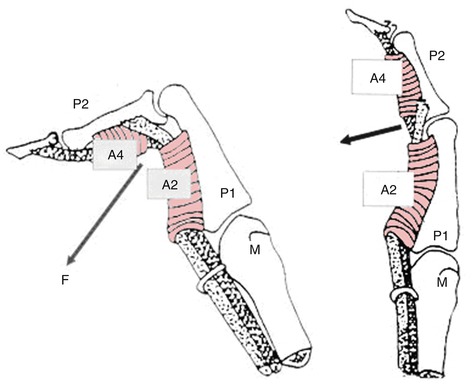

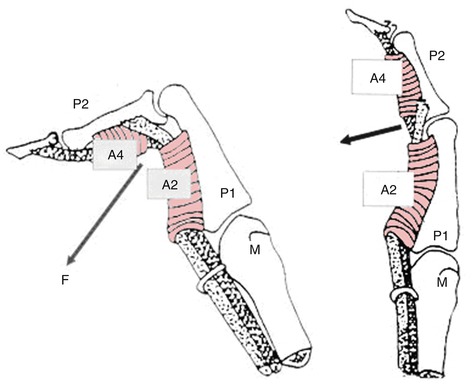

Therefore, the open hand posture requires an adjusted training time, because the climber has to maintain a perpendicular pressure to the hold, which is not so obvious according to the available surface. The pressure results from the part of the finger or the hand which is in contact to the hold. The pressure felt by a straight finger is higher on the last phalanx that is to say on P3. In that posture, the finger flexes the DIP joint with a slight flexion of the PIP joint too. According to L. Vigouroux, thanks to the open hand posture, the strain endured by the pulley is reduced – 32 times lower on A2 and 3 times on A4.

Quoting Grant and Al., Sweizer, Quaine, and Vigouroux, “considering an identical hold, no strength differences between the two postures have been reported whether at the highest intensity – used on the hold – or at the lowest point when finger muscles get tired.” Therefore, according to the shape, the size, the angle, the incline degree, and of course the climber’s skills, it is advised to use the open hand posture as much as possible.

Photo 5.3

Strength during the slope grip (Illustration inspired by Duval, La Main du grimpeur: approche physiologique, clinique et expérimentale, 1986)

Schema 5.1

Strength during the slope grip (Illustration inspired by Duval, La Main du grimpeur: approche physiologique, clinique et expérimentale, 1986)

The strength over the two tendons FDS and FDP is equally distributed in the open hand posture. EDC strain is another parameter to be considered. For now, a specific training for these two muscles has not been reported yet. Coaches and climbers have to pay attention to the involvement of the EDC and see how to reinforce them.

Most of the time, the open hand posture requires the use of the four long fingers for large holds, which allows better contact with the surface in grips. As training goes by, the climber is able to use this posture on locked or rounded holds, adjusting the necessary number of fingers according to the size of the hold or the available surface. The open hand posture enables the climber to broaden his skills, using the four long fingers or just one finger to seize the holds.

Concerning the two-finger posture, it is more advised to use the middle finger and the ring finger. Indeed, the open hand posture maintains a better structure stability and limits the possible lesions on the pulleys in crimp grip. The middle finger prevails, and it is supported by the ring finger. These two fingers are supposed to be the strongest (Duval 1986), but they are also the most currently injured (Quaine et al.). The location of these two fingers in the longitudinal axis of the hand makes them the most convenient to be used.

Photo 5.4

The slope grip

Photo 5.5

Two fingers in slope grip position

Tendinitis and tenosynovitis are the most current injuries resulting from the open hand posture. Most of the time, tiredness or exaggerated training accounts for these lesions. Some grips on steep holds or non-ergonomic supports tend to cause this kind of trauma.

Photo 5.6

Slope grip in a broad surface

5.1.1.2 Crimp Grip

This posture which is associated to clinging seems to be more natural for the beginner climber. For the advanced climber, the choice of this posture will depend on the width of the surface of the hold. The smaller and narrower the surface is, the more appropriate crimp grip is – with one or several fingers – even if the hold is flat.

In addition to that, this posture is more convenient than the open hand posture to reach a farther hold – due to the wrist’s position which is higher.

Photo 5.7

Strength during the crimp grip (Illustration inspired by Duval, La Main du grimpeur: approche physiologique, clinique et expérimentale, 1986)

Schema 5.2

Strength during the crimp grip (Illustration inspired by Duval, La Main du grimpeur: approche physiologique, clinique et expérimentale, 1986)

In crimp grip, two cases are possible:

The thumb is set on the index P3 phalanx. The pressure then brought on the phalanx is very strong on the surface level. But the pulleys are highly strained due to the angle of the PIP joint. In that particular case, the thumb acts like a finger locker to increase the strength.

Photo 5.8

Crimp posture

The thumb clings to the hold and opposes its strength to that of the fingers. This posture can be compared to that of the pliers grip though in the former case the strength involved is opposite. This posture is an intermediary between the open hand posture and the crimp grip posture, because the PIP joint angle is less broad and consequently the strength involved on the pulleys is reduced. This posture of the thumb is commonly used in CG, because the added holds on the wall make it possible, either on the edge of the hold or on a steep part, or a specific part of it, or simply on the screw hole – in competitions, some climbing leaders make sure to refill it, whereas some retailers reduce the screw hole so that only the head of the screw hole can be visible. In natural sites, this posture is not commonly used and depends on the bumps on the surface.

Photo 5.9

Crimp grip of the long fingers and pinch with the thumb

The crimp grip consists of a flexion of the PIP joint and a hyperextension of the DIP. Concerning the hardly hooked gripping – large holds – the pressure involved on the hold is focused on the P3 phalanx, which reduces the surface in contact.

This posture is a real strain on the A2 and A4 pulleys. According to L. Vigouroux, the A4 pulley is closer to its limit (85 %) than the A2 pulley (45 %). Indeed, the strength present on the A4 pulley is about 178.4 N, when its rupture point would be 210 N according to Lin et al. (1990). As regards the A2 pulley, the weight involved is about 200.2 N and its rupture point would be 465 N. The crimp grip posture is a real strain on the FDS muscle. FDP tendons and EDC extensors are active but to a lesser extent. Nonetheless, EDC activation is a factor to be considered as regards performances but also for the climber’s health. The EDC muscle plays an important part.

The breaking off a pulley is the most common injury. In addition to the size of the hold, other factors increasing the tension of this fiber structure – angle of the hold, number of supports, etc. – or a too tiring training session or a bad preparation accounts for this kind of lesion.

5.1.1.3 Mixed Hand Posture

This posture involves a vast number of possibilities mixing crimp grips and open hand postures. For a great part and for each finger in action, this posture requires the flexor muscle DCF mobilization (in the crimp grip posture) or to an identical degree FDS, FDP, and the extensors EDC (in the open hand posture).

The mixed posture requires a more advanced level in climbing due to the specific strains endured by muscles. It can be quite traumatizing.

Photos 5.10 and 5.11

Combined grip position

5.1.1.4 Hooked Posture

This posture consists of a flexion of the PIP and DIP joints. It is a global hold, and it is usually used on large holds.

5.1.1.5 Locked Grip

This grip usually requires the open hand posture. The climber inserts his fingers inside a hole or a crack and rotates his forearm inwardly. This phenomenon of locking reinforces the strength in presence. This grip can be painful or traumatizing for the joints (PIP sprains). The open hand grip generally improves the locking movement in seizing and consequently involves on a same level SCF and DCF without forgetting the extensors FCE.

Photo 5.12

Locked grip

5.1.1.6 Fist Grip

This way of gripping is more frequent in CG than in natural sites. The interest of this posture is that for the great part the hand flexors are involved – the palm of the hand is in contact with the surface of the hold. In that precise case, the surface in contact with the hand is large enough, so that the finger common flexors are slightly relaxed. This grip is convenient for large and rounded holds. Then it is easier to place the hand on the side above the hold and clutch the fist.

Photos 5.13 and 5.14

The knob grip

Photos 5.15 and 5.16

The knob grip

5.1.2 Crimp Grip or Open Hand Posture: Which One to Choose?

From beginner to advanced level, the climber improves his way of gripping discovering new and various holds. The fresh climber will limit his experience to the crimp grip posture, which is safer and more natural for him since the strength involved on the hold (hooked grip) allows him to be in contact to the structure.

Schema 5.3

Different grip (crimp and slope) simplifications (Illustration inspired by Voulliaume (D.), Forli (A.), Parzy (O.), Moutet (F.), Répartition des ruptures de poulie chez le grimpeur)

As previously explained, the open hand posture is gradually achieved through a right adaptation and training to master the proper and different weight to be applied on the last phalanx of the fingers used (P3). In open hand posture, the other phalanges (P1 and P2) can also be in contact according to the size of the hold. This method stimulates at the same time the FDS and FDP, which requires a muscular reinforcement of FDS since the tendon is much more strained in open hand posture than in crimp grip − 165. N in open hand posture versus 113.2 in crimp grip. This kind of practice requires a gradual muscular fitting.

Does that mean that it is much better to climb in the open hand position? For sure the crimp grip is a stronger strain for pulleys – especially the A4 pulley on which the risks of rupture are higher – but it is also more convenient to seize the small and not too deep holds. Besides, according to the climber’s hand morphology and level, the open hand position does not always help him to maintain a hold, which makes him quite uncomfortable. Indeed, a quite long middle finger or a too short little finger may be a source of trouble. Therefore, the enlightened climber has to adapt to his morphology and his skills, combining the open hand, crimp grip, or mixed position. In order to reduce the number of lesions, the climber has to be trained in all these different techniques. Nonetheless, the advanced climber has to put forward the open hand posture to limit the tension on the pulleys. Outdoors, during high-level competitions, and to achieve good results, fingers are excessively prompted. This is why open hand posture relieves some of the finger tension especially over the pulleys. After a finger injury, during a period of reeducation, this posture combined with a proper strapping is highly recommended. The adaptation to the crimp grip posture will have to be gradual, as will be explained further in this document.

Photo 5.17

For a climbing expert, the maximal intensity measured on a same hold is identical whether he uses the open hand or the crimp grip. It would be quite interesting to train the fresh climbers to use more often the open hand posture. Climber coaches have to bear in mind this phenomenon to preserve the beginners from finger injuries. The sooner a great variety of seizing holds is learned, the more aware and less injured the fresh climbers will be. The more trained the young climber is, the more experimental he is, and eventually he becomes more qualified to choose the righter and safer finger posture according to the situation throughout his future sports career.

Photo 5.18

5.2 Training Basics

This part of the book will deal with a few basic principles to avoid any mistakes during training practice. Further information concerning the different fields and the training planning can be found in many other books even if a bad training planning can lead to a lesion. A good planning aims at helping the sportsman or the competitor to be fit on a D day or at maintaining the climber to be outstanding during a certain period of time.

5.2.1 Intensity Principles

In order to avoid an exhausting training, the athlete has to adjust the quantity to the intensity of the work. During the physical preparation (PP), the training sessions have to be numerous so that the body may get used to effort and sustain the following sessions which will be more numerous and intensive. The more voluminous is the training session, the lower the intensity has to be, and reciprocally. It is dangerous to have enormous sessions in PP with routes close to the maximal level of the climber. During a specific preparation (SP) for a competition, the athlete’s training sessions are focused on the specificities of the competition. The intensity is close to the maximum level or supramaximum, and the time to recover is longer. Indeed the body needs a certain amount of energy to try the route again.

The intensity principle has to be considered throughout the session. Warming-up is a priority to prepare the different muscles and joints, though a great number of climbers tend to forget it and prefer climbing gradually. Defining a specific time to get an optimal warm-up is quite difficult. It depends on the daily physical condition, the level of tiredness, and the aim of the session. Being aware of one’s own body and paying attention to any physical signs are consequently extremely important.

5.2.2 Alternative Principles

Alternative principles can be divided into two categories:

5.2.2.1 Grip and Support Alternatives

The great number of possible positions makes climbing a varied and exciting sport, especially outdoor climbing which involves a great variety of grips and movements. Each climber has his own style with his strong and weak points. The climber has to train on various supports to be as efficient on any of them but also to avoid injuries. Working an unknown posture intensively may lead to a trauma. Climbing in different kinds of routes is a good way to broaden one’s skills and to use the various joint and muscular chains and consequently to become an expert. As regards fingers, the climber has to be able to seize holds differently, especially if he wants to be highly competitive, outdoors or indoors. The repetition of the same movement is a high strain on the tendons, joints, and pulleys. Repeating over and over the same gesture remains a possible cause of injury.

5.2.2.2 Training Session Alternatives

Alternating route training, intensity and volume, is a good means to avoid psychological pressure. Indeed, if the athlete feels competent and determined and enjoys what he does, he will achieve more good results and the training sessions will be more efficient. The training sessions need to be varied including different drills even if the aim is identical. Emotionally speaking, it is generally hard for people to reproduce the same work for 3 days on. The lack of motivation may cause an injury. Giving a sense to each activity is a motivation factor. This is why the sportsman has to understand what he does to put a lot into the training session.

Alternative is the key word for a healthy body. The former helps the latter to remain in activity and to recover after a specific training session. Obviously, alternative is good for the body, but it is also a complementary way to deal with the emotional load resulting from the undergone efforts. Changing the training routes, telling himself that a hard session won’t be repeated, and alternating the intensity or the volume of a session are the many means for the climber to take a deep breath.

To make the recovery easier, training cycles alternate between intensive and less intensive sessions. The issue in alternative would be to do the wrong thing. A logic principle has to be respected and depends on the different fields and the required time to recover. The training planning has to consider the notion of pleasure too.

5.2.3 Progressive Principles

The intensity and the volume of the training have to be reversed in order to avoid a habit in the body and to reduce possible trauma. After a full stop practice for whatever reasons – lesions, family matters, or personal reasons – it is dangerous to start practicing again at the highest level, because the body has more or less got out the habit of intensive efforts. Consequently, it is advised to start slowly and to increase gradually the intensity throughout the training sessions.

After an injury, the time to regain one’s higher level is usually more or less double that of the rest period due to that lesion.

During a training planning and a regular practice, the principle of overweight is essential. To improve a prior factor of the performance such as the strength of the fingers, it is necessary to work on them by overloading them. For instance, the size of the grips, the number of supports, and the footholds can be reduced. Indeed, if the climber works only on good grips and comfortable footholds, he won’t develop his strength. On the other hand, once back to training, if he overworks on a hangboard or on a campus board, he might get finger lesions.

Progressive principles imply the fact that training sessions have to be global and then specific. At the beginning of each season, the coaching of a lead climber and that of a bouldering climber of the same level tends to be similar. As the season unfolds, the sessions differ completely for each climber and the training becomes more specific.

The aim is to evolve and turn quantity into specificity. The climber reduces the number of route attempts and focuses on particular movements according to the objective of the session or the cycle.

If a climber or a coach wants to make a progressive training, before defining a training session, they have to think about the tiredness factor and its impact.

5.2.4 Constancy and Continuity Principles

Usually, interrupting climbing training whatever the reason and for more than a week is bad for a good preparation. Achieving good results, whatever the level, requires a more and more complete and demanding involvement. Going back to training is always a difficult time for climbers who do not perfectly know their bodies and their limits. For the most skilled ones, it is usually a frustrating period, because they are so eager to be at the top again that they often tend to do away with reeducation phases. An interruption – even if it has been only for 2 weeks – implies a gradual return to practice in order to avoid any injuries or recurrences. Several factors such as non-strained fingers or a not complete healing enhance the possibility of a new wound. A gradual return to practice is consequently highly recommended especially in case of former lesions. Initially, fingers have not been made for rock climbing; this is why they have to be protected.

A practice interruption involving no injury is to be banned, especially for someone preparing for a competition or a precise aim. This kind of interruption requires a change in the training planning to find the right balance between the daily activities to be fit for the D day.

After an intensive cycle and to make the recovery easier, it is healthier for the body to undergo a couple of less intensive sessions and to insist on the notion of pleasure or technique rather than stop practice completely. In case of injuries, the interruption must not be definitive. In fact, to maintain one’s form, a muscular training has to be followed including working out, electrostimulation, jogging, etc.

Photo 5.19

5.2.5 Specificity and Characterization Principles

Climbing training has to be specific according to each individual. This principle has been widely reported due to the fact that each athlete responds differently to a given weight. Indeed, on the one hand, for an identical weight, the amount of work can be sufficient for an athlete, but on the other hand, it can be over the top for another athlete. Quoting Weineck, “Such a training method is perfect for one but is an extra work for the other one.”

The quality of training depends on characterization. All of the sportsmen do not have the same physical capacities, needs, experiences, levels, or objectives.

Several factors have to be considered:

Age

Psychomotor development level

Sports level

Gender

Past experiences

Objectives

Special field

The coach has to take a closer look at the climber’s social life. The latter’s love life, work, or future exams are important facts to be taken into account for the training planning.

5.2.6 Knowing and Listening to One’s Body

This principle is the most complex of all the others, because only the athlete can tell how he feels and notice any pain in his body. The coach is supposed to detect any changes in the athlete’s state of mind – a feeling of desire, tiredness, or pain – but he can’t measure the intensity of them. It is a priority to understand that pain is a signal sent by the body to protect itself. When there is a pain, there is an injury –more or less serious. The sportsman has to tell the difference of the “good pains to the bad ones,” more precisely the ones felt in the forearms when the lactic acid is flowing.

Several parameters have to be considered:

Physical tiredness due to intensive sessions, cycles, and/or extra activities outside training practice. As regards young people, the concern lays in PE or their social life which can bring an excess of tiredness.

Moral tiredness results from the intensity of the last few sessions (or the last one), a lowering in motivation, or other external factors such as school/work tiredness, family matters, or social life problems.

This is why it is extremely important to talk to each athlete and help him to have a better understanding of his body. The coach has to adjust his training session according to the athlete’s present state of mind. The sportsman’s degree of concentration has to fit the required activities.

Photo 5.20

5.3 Climbing Various Efforts

Training with specific tools such as a campus board or a hangboard requires high skills to avoid any lesions. These appliances are a real strain for fingers which may endure extra weight if exercises are not well adjusted. The climber has to be precisely aware of what he is working on, because according to the field – alactic anaerobics, lactic – the effort times and the rest periods will change. If you do not rest properly after a training session based on strength, the previous effort will turn into an effort on resistance and therefore increase the risks of lesions.

In this book which deals with hand injuries, it is obviously necessary to mention a few things about the different kinds of fields so that possible lesions due to bad training practice can be reduced. Nonetheless, the subject being wide, it is hard to elaborate on the training topic, and further information will be found in other documentations.

5.3.1 Alactic Anaerobic Efforts

This effort consists of very intensive exercises on a maximal power. This category is entitled to work on strength liberating a great source of energy in a short time. During the session, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and also a small amount of creatine phosphate (CP) are used. When they are solicited at their maximum level, the very short reserves are used out after 7 s. This lapse of time is consequently a reference time in rock climbing practice. Climbers often mention the number of movements fulfilled. It is much better to work on the notion of required effort, which is more understandable. According to the movement, the quantity may change.

The aim of the training is to remain focused on the available energy and use it efficiently.

Alactic Anaerobic Intensity Recap

Intensity: maximal or supramaximal (>100 %).

Duration of the effort: between 3 and 7 s.

Recovery: between 1 min 30 s and 3 min.

Repetition of the movement: about 10. The climber has to stop the repetitions when he notices a decrease in intensity.

Alactic Anaerobic Capacity Recap

Intensity: between 90 and 100 %.

Duration of the effort: between 7 and 15 s.

Recovery: between 3 and 8 min.

Repetition of the movements: from 6 to 10. If the climber notices a decrease in intensity, he can reduce the duration of the effort which allows a great amount of work.

5.3.2 Lactic Anaerobic Efforts

This category begins on the first second but on a very low intensity. The intensity is higher after 10 s. The strength in use is high but not maximal. The intensity grows from 30 to 45 s according to the required effort. The function of the training is to develop a resistance against “lactic poisoning.”

Alactic Anaerobic Intensity Recap

Intensity: maximal.

Duration of the effort: between 15 and 45 s.

Break between two repetitions: from 30 s to 3 min in order to get a partial recovery of the basic potential.

Break between two series: from 5 to 30 min in order to produce another effort of the same level.

Repetition of the movements: between two and six. It is important to judge the intensity of the effort properly. The session has to be stopped when the climber is unable to make a new effort with a sufficient intensity.

Alactic Anaerobic Capacity Recap

Intensity: the intensity has to be 80 %.

Duration of the effort: from 45 s to 2 min.

Break between two efforts: 2 min.

Number of repetitions: between 5 and 8.

Recovery between two series: 6 min.

Number of repetitions: between 6 and 8. In order to work sufficiently, the climber can reduce the duration of the effort and increase the recovery time.

5.3.3 Aerobic Efforts

It is false to believe that aerobics is useless in rock climbing. Of course rock climbing practice does not really appeal to aerobics, but it is nonetheless quite appropriate especially as regards PP.

Lesions being the main topic of the book, aerobics is first of all a good means to prepare the body of the athlete for the next season. All the energetic processes are developed through aerobics. But above all, it is a means to prepare ligaments and tendons for efforts.

In climbing, an increase aerobic process improves the recovery between two efforts. It can be quite useful in bouldering competitions, especially when the climber is allowed 6 min of recovery between two route attempts. Aerobics is also a good means to evacuate lactic waste – due to muscle contractions – and to improve the cardiovascular system.

Photo 5.21

5.4 Various Competitions of Rock Climbing

Climbing competitions can be divided into three categories: speed, lead, and bouldering. In climbing terminology, a route or a boulder is done on sight, when no former attempt has been done except for the given time of observation. On the contrary, when a climbing leader performs successfully, it is called a “flash performance.”

5.4.1 Lead Competitions

In climbing, lead category is the most well known. Competitions take place in CG. The aim is to reach the top of the route. Though a limited time is required, it is the reached height which determines the rank. Time is not used to choose the winner. It is just a way to prevent too long performances. In case of equally placed athletes after the first round, the jury takes into account the height reached in the former round. If the finalists are still placed first, a super final is organized.

5.4.2 Bouldering Competitions

In climbing, a boulder is a short passage. The aim is to achieve a great number of passages. Two kinds of competitions exist:

A circuit which is set for France championships and international competitions. According to the competitions and the rounds – qualifications, semi-finals, or finals – climbers have to pass between four and six boulders within 4–6 min. Between two passages, climbers are entitled to a break corresponding to the time allowed for the passages. In those kinds of competitions, climbers are isolated even during the qualifications. They are ranked according to the number of passages they have succeeded. In case of equally placed athletes, the number of attempts is first counted, then the number of areas achieved successfully (with specific holds chosen by leaders especially after a first difficult part), and, finally, the number of attempts to reach the holds in these areas.

A contest which consists of two rounds: qualifications and finals. During the qualifications, climbers are not isolated and have to achieve a maximum of the requested passages. Then the five best qualifiers take part in a flash or an on-sight final. In finals, climbers are allowed to make as many attempts as they want.

5.4.3 Speed Competitions

This practice is the oldest one. The aim is to reach the top of the route as fast as possible. These competitions are rare in France but commonly practiced in East countries.

Routes are climbed with a top rope. Competitions are divided into two parts: qualifications and finals.

5.5 Outdoor Climbing

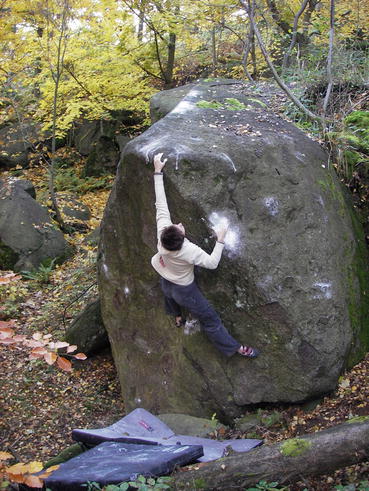

Photo 5.22

(sur la droite)

Boulder and route difficulties are classified by grades, which correspond to the technical difficulty of the passage – height, slope, succession of holds, and sizes of holds. Marks remain biased and depend on each athlete’s strong and weak points. The climbers’ morphology can be an advantage or a disadvantage in some passages.

In France, route rating starts on 3 and stops on 9th degree. Each degree is divided into three parts: 6a, 6b, and 6c. There are also intermediary degrees – 6a+, 6b+, and 6c+. Several difficulty levels have been applied.

As regards bouldering categories, several ways of rating are available even in France.

5.6 Training

Climbing development has led to the appearance of new specific training supports, such as the hangboard and the campus board. Obviously, they are a good means to develop finger strength and/or finger resistance intensively, but due to the extreme finger strain they require, they can be the source of new lesions, more or less serious.

5.6.1 Safety and General Precautions

Numerous factors have to be taken into account before training with these specific tools. First of all, they are addressed to very high-level climbers. A beginner is not allowed to use one of these appliances because his body won’t be able to endure the strain. These tools are actually designed for highly skilled climbers (6c/7a) who lack strength and would like to progress. But above all, they are addressed to athletes who would like to achieve excellent results in competitions, outdoors or on CG for fun.

Because of growth problems – especially as regards finger cartilages – these sorts of tools can’t be used by 16-year-olds, that is to say, until the teenager is physically mature enough to undergo the possible side effects of intensive climbing practice. This stage is hard to recognize for sure, especially when each adolescent is different from the other, but at least the age limit is a good means to reduce risks. In the long run, finger-intensive training can lead to after effects which can turn a sportsman’s career short. Adolescence is the right period to develop motor learning. But this stage can’t be the same for everybody, since each teenager has his own specificity and consequently will develop according to his own phases or rhythm. At that age, training consists of learning a great number of climbing movements and facing various situations, focusing on the teenager’s feelings in each case. In the second puberty phase, the muscular development and the higher capacity to understand and create motor designs are perfect to improve performances. This period is ideal to learn all the climbing-specific physical skills. Just like the use of the particular appliances, the specific skills require a precise adjustment. For instance, climbing with no foot is a good exercise before dealing with the hangboard or the campus board.

The use of this specific equipment is to be banned when one goes back to climbing practice, after a complete interruption or any lesion. The extreme strain requested by these tools can lead to a recurrence or a new injury for the climber. The body structure may not be well prepared, healed up, or strong enough to endure such a strain. These devices will be part of the specific training and won’t be used before a proper reeducation and a few climbing sessions.

A gradual and complete warm-up is a good means to be more efficient during training sessions, but above all, it allows muscles and tendons to support the strain without getting injured. It has to be complete from generalities to specificities and has to last about 15–20 min. Besides, at the end of the training, it is important to stretch the muscles in order for them to regain their initial length. Repetitive contractions, especially concentric ones, tend to shorten the muscles which then become more fragile. It is a priority to bring them back to their initial size.

During a session, it is advised to combine climbing movements on artificial structures and the use of the specific equipment. This combination tends to enhance strength, without forgetting technical gestures, and mobilize the upper and lower part of the body. Consequently, it is important to make this association to get good results.

Photo 5.23

Crimp grip on a reverse hold

5.6.2 Training Safety

Training on this specific equipment requires a particular preparation due to the intense strain endured by the muscles and joints. This is why these tools can’t be used at the beginning of a session, because they are a real strain not only on the flexors. The body needs a period of adjustment to deal with this kind of pressure. These specific appliances can be added during the second phase of the PP and will complete the specific training according to the category – bouldering or lead – during the SP. During the PP, the training is first global even if the types of exercises (training circuit) are supposed to reinforce muscles without neglecting the antagonist muscles to maintain a proper balance.

During the second phase of the PP, the use of these specific tools can be replaced by “no foot” exercises on a campus board, which prepare the muscles gradually to concentric and eccentric contractions. The athlete or the coach can introduce these tools little by little and for a short while, in the training.

In SP and according to the chosen objective, the preparation can be focused on these appliances by the coach. The exercises are so demanding that most of the time the athlete is close to his limits. The training sessions must not exceed 45 min or 1 h (warm-up included), and long periods of recovery between each activity or repetition have to be taken.

Whether in PP or SP, the cycle on these tools must not exceed 3 weeks and has to be followed by a recovery cycle in order to gain strength and to avoid any tendon traumas (flexors and extensors). Three sessions a week is the maximum number during a cycle. Between the sessions, the period of recovery changes according to the aim: to gain strength, 24 h; to develop resistance, 48 h; and to maintain strength, 72 h.

To reduce any possible injury, it is highly recommended not to carry extra weight, especially during strength cycles. In theory, working with additional weight might increase strength, but it is also a supplementary strain on the tendons which are first designed to support the body weight. Fingers are not designed to bear climbing weight. Consequently it is much better to work on various grips, focusing on a specific category and according to the objectives of each cycle or session. On the other hand, working on grips is a good means to work on one’s strong and weak points. Using in turn the different holds (buckets, small edges, large holds, or round edges) and changing the fingers’ posture (open hand or crimp grip) lead to a more global work on strength. To relieve tendon strain, it is advised to use the slope posture rather than the crimp grip.

5.6.3 Training on Specific Tools

5.6.3.1 Hangboard Sessions

Introduction

The hangboard is used to develop muscular abilities which are specific to rock climbing and precisely concern the different holds in suspension that can be reproduced with this equipment. This tool enables the climber to develop specific muscles and more precisely “no foot” training. Hanging work prevails and is a good help to emphasize a specific work on the duration of the holds. Moving on the hangboard is possible though quite limited. This training leads the climber to be more precise in his movements, since it helps the coordination and synchronization of the fingers’ opening and closing.

The hangboard is not only a training tool, but it is also a device used to end the warm-up in a more specific way. In that particular case, the climber is fitter to start the ongoing activity, but he has to follow a gradual warm-up. Likewise, the climber uses first the comfortable holds (buckets) remaining shortly suspended, and then he gradually turns to smaller holds. It is strictly forbidden to hang on tricky holds or to make extreme movements, especially when he has not warmed up properly.

Possible injuries resulting from the hangboard not only affect the fingers but also the shoulders, elbows, or other parts of the body. The warm-up has to well prepare all the joints and the different structures of the scapular belt and the arms. The hangboard is an excellent tool, but if “the golden rules” are not respected, it can be extremely dangerous for the climber’s health.

Here are a few rules to be respected:

Never work loaded. The climber chooses smaller holds to work properly in the chosen category.

Respect recovery time.

Never use the crimp grip. This posture is a real strain for the fingers and is reinforced when the feet are not used.

Train only if you are perfectly fit.

Warm up all the joints, including the finger joints, before practicing.

Several types of exercises are possible with the hangboard, but we will focus on those improving the duration of the holds (dynamic efforts will be dealt with the campus board) and those concerning isometric efforts.

A training hangboard is chosen according to the holds which must not be “traumatizing” (“overusing”). A hangboard has to be deprived of too steep angles, and the posture of the fingers has to be convenient.

Photo 5.24

Training session with a wooden hangboard

Strength Development

After these kinds of sessions, the climber feels as if he has not done anything.

It is important to change the grips, in order to broaden one’s skills and not to be limited to one particular way of seizing.

Principle: the climber hangs on holds, with one or two hands in the open hand posture. He is supposed to remain like that for 7 s maximum. To assess properly the intensity and if the hold becomes too easy, it is advised to reduce the size of it, even if the weight is reduced, rather than working loaded.

Duration of the effort: from 5 to 7 s.

Break between two efforts: 3 min minimum.

Repetitions: from 5 to 10.

Resistance Development

Training Session First Example

Principle: the exercise has to be fulfilled on the chosen holds: consequently, they must not be too small. In order for resistance to work, the climber has to remain suspended for at least 20 s.

It is possible to work with different degrees of closing arms.

Duration of the effort: between 20 and 45 s.

Break : 30 s.

Repetitions: between 5 and 8.

Break between two series: 5 min.

Number of series: 4.

Training Session Second Example

Principle: choose a hold to be able to remain suspended with one or two hands for 1 min.

Duration of the effort: 1 min.

Break between two repetitions: 2 min.

Repetitions: 3.

Break between two series: 5 min.

Number of series: 3.

5.6.3.2 Campus Board Sessions

Introduction

Just like the hangboard, the campus board is a powerful tool to work on the different anaerobics categories. Various movements, which can be fulfilled with one arm at a time or with both of them, develop dynamism, contact strength, and alactic anaerobic field.

Photo 5.25

Training session on a campus board

Safety regulations and recommendations are identical to those of the hangboard. This equipment requires a specific preparation such as the “no foot” on campus board, with a variation of holds and/or similar exercises. The climber can reproduce the same kind of effort using traction bars.

This appliance is ideal to work pliometric efforts. In that particular case, it is highly recommended to be cautious with finger structures which are much requested. Indeed, when the climber lets himself go on the lower hold, an extreme contact strength is involved. Once again, a specific preparation is compulsory.

Due to the extreme strain involved, it is advised to limit the number of sessions with a campus board. To begin with, one session a week seems to be sensible. Then as the climber becomes more skilled, he can practice two or three sessions a week maximum. The cycle must not exceed 3 weeks, so that the body can recover properly.

Strength Development

Training Session First Example: Dynamic Movements

Principle: choose holds on which the climber will be able to make up to five movements. The aim is to make movements farther and farther on smaller and smaller holds.

Number of movements: from 1 to 5.

Break between two repetitions: 5 min.

Repetitions: from 5 to 10.

Training Session Second Example: Dynos

Principle: choose holds on which the climber will be able to make a dyno with two hands. The aim is to reach a distant hold and when possible to make this movement in chain. The holds have to be large enough to reduce possible injuries.

Number of movements: from 1 to 5.

Break between two repetitions: 5 min.

Repetitions: from 5 to 10.

Resistance Development

Principle: choose holds on which the climber will be able to make at least ten movements.

Number of movements: the climber has to go up and down a campus board for at least ten movements.

Break between two series: 5 min.

Number of series: 5.

Photo 5.26

5.7 Return to Training After an Injury

Several reasons such as holidays, working life, or injuries can be the origin of an interruption in sports practice. In case of a lesion, it is quite different, and climbers and coaches have to be extremely cautious. Indeed, after an interruption, the body is not anymore used to the former practice. Therefore, it will react differently; physical abilities won’t be the same, and consequently, the body won’t be able to endure the former intensity and complexity required by the training. In that part of the book, we will deal with the basics of a return to training, bearing in mind that each session has to be characterized. The sportsman characteristics have to be considered, because each athlete is unique and so are his psychological state (motivations, objectives), physical abilities (skills, tiredness, recovery time, diet), anatomy (morphology, former injuries), and social life (leisure time, family, and working life).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree