Total Knee Arthroplasty in Rheumatoid Arthritis

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis has unique features different from those encountered in patients with osteoarthritis. Through the years, I have taken care of a large number of patients with rheumatoid arthritis requiring TKA—both adult and juvenile patients. When I started practice in 1975 at the Robert Breck Brigham Hospital, 85% of patients undergoing TKA had rheumatoid arthritis. Since that time, this percentage has reversed itself to the point at which less than 5% of my patients have rheumatoid disease. Multiple reasons account for this change. The percentage of patients with rheumatoid arthritis was high in the mid-1970s because TKA was new and many potential candidates were withheld from the surgeon’s care until the success of the procedure was established. Once the backlog of patients had been operated on, the percentage of patients with rheumatoid arthritis decreased. Another factor was the training of residents and fellows who stayed in our geographic area. They had developed their own expertise with this procedure, and fewer patients with rheumatoid arthritis were referred to our center. A third important reason for the decrease is the marked improvement in the medical treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Fewer patients now progress to the stage of permanent structural damage requiring arthroplasty.

Ipsilateral Hip Involvement

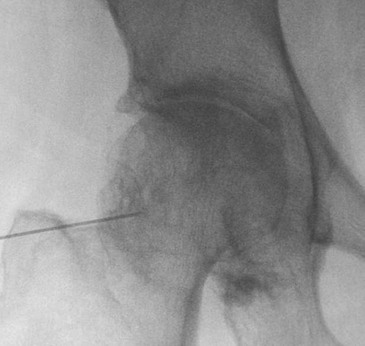

Ipsilateral hip involvement is more frequent in rheumatoid arthritis than in osteoarthritis. The hip should always be thoroughly evaluated before TKA, and with few exceptions, the hip should be replaced before the knee surgery. I can think of at least six reasons for this. The first is that it is best to first resolve any knee pain that is referred from the hip. At times, the knee arthroplasty can even be delayed owing to the pain relief gained by replacing the hip. In cases in which it is critical to resolve the source of the knee pain, the hip joint should be injected with bupivacaine under fluoroscopic control (Figure 10-1). The patient can then report on the extent of pain relief gained. If the pain relief is considerable, both patient and surgeon are more comfortable with the decision to proceed with the hip first.

The second reason is especially important in the juvenile patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Because the hip surgery is relatively easy and painless for the patient (compared with the knee surgery), the surgeon gains the patient’s confidence. On the contrary, if the knee is operated on first, the pain and difficult rehabilitation that the patient endures without a significant gain in function discourages the patient who still has pain and lack of function.

A third related reason is the fact that a person can exercise a hip above a painful arthritic knee, whereas it is difficult to exercise a knee below a painful, stiff, arthritic hip. I believe that a stationary bicycle is extremely helpful during rehabilitation of knee arthroplasty but is not important to rehabilitation of a hip replacement. The use of a bicycle is not possible when the hip above is painful and stiff.

The fourth reason is to resolve the tension of muscles that cross both the hip and knee joint, especially the hamstrings. If, for example, both hip and knee have flexion contractures and the knee is operated on first, resolving that contracture, a subsequent hip replacement that lengthens the hip can retighten the hamstring muscle.

The fifth reason also is related to preoperative knee contractures. At the time of hip arthroplasty, a contracted knee can be manipulated and casted to improve passive extension before the knee replacement. If epidural anesthesia is used, it can be maintained for several days and serial casts can be applied (see Chapter 8, Figure 8-2).

Sixth and finally, it makes sense to avoid twisting and torqueing a well-balanced TKA while dislocating and exposing a stiff hip for replacement.

Anticoagulation Needs

In my experience, deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary emboli occur less frequently in patients with rheumatoid arthritis than in those with osteoarthritis. This may be partially due to the fact that most patients with rheumatoid arthritis require the chronic use of antiinflammatory medications, which have a mild anticoagulation effect. It might also be intrinsically related to their disease process. The reason is unclear, but it makes their anticoagulation needs different from those of patients with osteoarthritis.

For all my TKA patients, I begin dosing warfarin on the night before surgery. For the patients with rheumatoid arthritis, I adjust the dose of warfarin during their hospital stay to an international normalized ratio between 1.5 and 2. Before discharge, I screen for DVT with an ultrasound examination. If it is negative, patients are discharged home on 325 mg of aspirin twice daily plus a return to their normal antiinflammatory medication. I usually consider patients who have undergone bilateral simultaneous knee procedures at higher risk for DVT and maintain them on an adjusted dose of warfarin for at least 4 weeks. I make an exception for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and bilateral knee procedures who require their antiinflammatory medication for control of rheumatoid inflammation. If bilateral ultrasounds are negative for DVT, they also are discharged on 325 mg of aspirin twice daily along with their rheumatoid medication.

Flexion Contracture

Flexion contractures are more prevalent in rheumatoid arthritis than in osteoarthritis. The contracture is more likely to be due to inflammation in the soft tissues, whereas the flexion contracture of osteoarthritis is usually associated with a bony block (see Chapter 8). After studying the outcomes of a large number of patients with severe contractures, I have developed the following treatment guidelines for patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

For flexion contractures less than 15 degrees under anesthesia, I perform a normal distal femoral resection and posterior capsular stripping as needed. If the flexion contracture is between 15 and 45 degrees, I increase the distal femoral resection by 2 mm for every additional 15 degrees of correction that is necessary. I do this to a limit of a total of 13 mm to avoid compromise of the femoral origins of the collateral ligaments.

Between 45 and 60 degrees of flexion contracture, I consider preoperative manipulation and casting and always use a posterior cruciate ligament (PCL)-substituting technique. For flexion contractures greater than 60 degrees, I also consider preoperative manipulation and casting (see Figure 8-2) and a constrained articulation such as a Total Condylar III (DePuy, Inc, Warsaw, IN) to resolve flexion gap laxity that can result from significant elevation of the femoral joint line.

For patients with inflammatory arthritis, I follow the “rule of one third.” This states that intraoperative correction need only be to within one third of the preoperative contracture under anesthesia. The residual one third usually resolves with physical therapy, resolution of the inflammatory disease, and occasionally the help of manipulation and casting. The most dramatic example I have seen was a patient with bilateral 110-degree flexion contractures. One knee was ankylosed at this degree of flexion, and the other knee was fused. The techniques described previously were used, including the Total Condylar III prosthesis. At the end of surgery, the flexion contracture was corrected to 40 degrees. After three serial casts applied under epidural anesthesia over 3 days, the patient’s flexion contracture was corrected to zero.

Several additional points regarding flexion contractures should be emphasized. If the patient has bilateral, severe flexion contractures, both should be corrected simultaneously to avoid the risk for regression of the correction on the first side until the second side is corrected.

When the capsule is closed after correction of a severe flexion contracture, the medial capsule should be advanced distally on the lateral capsule to avoid an initial extensor lag (see Figure 7-5).

The amount of posterior slope applied when dealing with a severe flexion contracture should be zero degrees. Every degree of slope built into the tibia creates a degree of flexion contracture or, put another way, prevents its correction.

Finally, ancillary preventive measures should be taken after surgery, such as allowing the patient to have a roll under the ankle but never under the knee. A knee immobilizer at night will prevent the patient sleeping with flexed knees and redeveloping a contracture. A dynamic extension splint can be helpful to both correct and maintain extension in refractory cases.