Total Knee Arthroplasty After Osteotomy

Conversion of osteotomy to total knee arthroplasty (TKA) can be extremely difficult for multiple reasons. These include the presence of prior incisions, difficult operative exposure, the presence of retained hardware, joint line angle distortion, malunion, nonunion, patella baja, offset tibial shafts, and relative deficiency of the lateral tibial plateau (Figure 9-1).

Incisions made before a standard TKA exposure must be respected. Unlike the hip, the knee does not tolerate multiple parallel or crisscrossing incisions. The vascular supply and lymphatic drainage are dominant on the medial side, resulting in a lateral flap being most vulnerable. Susceptibility may be increased when a lateral retinacular release has been performed to correct a valgus deformity or patellar tracking with compromise of the lateral superior genicular vessels. The most vulnerable knee is one with a long lateral parapatellar incision when the surgeon plans a parallel median parapatellar incision for a medial arthrotomy (see Chapter 14). Unfortunately, this type of incision has been used frequently in the past for osteotomy by some surgeons. When a long lateral incision is used, it must be extended and a medial flap raised to perform a standard medial arthrotomy. If the osteotomy is in marked valgus and the surgeon is familiar with the lateral approach, a lateral incision and lateral arthrotomy can be performed. Most experienced osteotomy surgeons now use midline incisions or short oblique incisions that can either be used easily later for TKA or ignored.

An oblique lateral incision (Coventry method) from the fibular head to the tibial tubercle, for example, can be ignored. If the surgeon is contemplating making a new medial incision parallel to an old lateral incision, the delayed technique or sham incision can be considered (see Chapter 14).

Operative Exposure

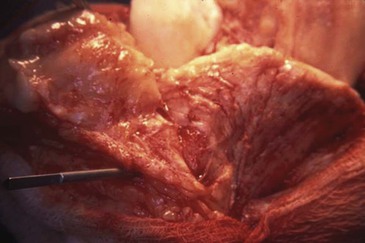

Because postosteotomy patients sometimes lose mobility and have scarring around the osteotomy site, exposure can be difficult. Exposure also is compromised by the presence of patella baja. For this reason, a proximal quadriceps release is usually appropriate to protect the patellar tendon (see Chapter 7). A smooth  -inch pin placed in the tibial tubercle further protects the patellar tendon from avulsion (Figure 9-2). Dissection in this area can be compromised by the healing of the osteotomy, and the surgeon must proceed with care.

-inch pin placed in the tibial tubercle further protects the patellar tendon from avulsion (Figure 9-2). Dissection in this area can be compromised by the healing of the osteotomy, and the surgeon must proceed with care.

Patella Baja

Patella baja often follows osteotomy. The surgeon can employ several techniques to resolve this situation (see Chapter 8). These include attempts to lower the joint line by decreasing the distal femoral resection and increasing the proximal tibial resection. When this is done, the anteroposterior cam of the femoral component should be moved posteriorly to prevent flexion gap laxity caused by lowering the joint line (see Figure 8-5).

The patellar thickness should be minimized and the patellar tendon freed from scar around the tubercle and proximal bone. Sometimes the inferior portion of the polyethylene of the patellar component and the anterior portion of the polyethylene of the tibial component have to be relieved with a rongeur or similar tool to prevent impingement of the patellar plastic on the tibial plastic. At the time of closure, the medial capsule is advanced distally on the lateral capsule to allow the patella to be pulled as proximal as possible (see Figure 7-5).

Retained Hardware

The presence of previously placed hardware about the knee after an osteotomy can present problems owing to the need to remove the hardware and the prior incisions used to implant it (Figure 9-3). Some hardware can be retained if it does not cause symptoms and is not located where it would impede placement of the components (Figure 9-4). If hardware does have to be removed, the decision has to be made on whether to remove it as a separate procedure or at the time of arthroplasty. Screws and staples usually can be removed at arthroplasty. Plates that have to be removed through a large separate incision are probably best removed 4 to 6 weeks before the arthroplasty, giving the separate incision time to heal. If concern exists about chronic low-grade sepsis at an osteotomy site or a hardware site, cultures can be obtained at the time of hardware removal.

Up-Sloped Joint Line

Joint line distortion after osteotomy can be in two planes. Abnormality in the varus–valgus plane is discussed later. In the flexion–extension plane, the most common distortion is a conversion of the normal down-slope of the tibia in the sagittal view to an up-slope of varying degree (Figure 9-5). The up-sloped joint line demands a tibial resection at 90 degrees to the long axis of the tibia in the sagittal view. Down-sloping the cut must be avoided because of the abnormal amount of bone that would need to be resected from the posterior aspect of the tibia and the resultant distortion of knee kinematics. It is often difficult to preserve and balance the posterior cruciate ligament in the presence of an up-sloped joint line.

Nonunion

When an osteotomy fails as a result of nonunion, the conversion to TKA must involve addressing the nonunion. I have had consistent success using a technique that prepares the tibia in a standard fashion but uses a long-stemmed tibial component to internally fix the nonunion (Figure 9-6). The fibrous tissue of the nonunion is accessed from the intramedullary hole for the stem and circumferentially curetted. This area is then grafted with bone obtained from the standard resections from the femur, patella, and tibia.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

-inch pin protects the patellar tendon from avulsing.

-inch pin protects the patellar tendon from avulsing.