Patients with potential bone and soft tissue tumors can be challenging for orthopedic surgeons. Lesions that appear benign can still create anxiety for the clinician and patient. However, attention to a few key imaging and clinical findings is enough to correctly diagnose five of the most common bone and soft tissue lesions: lipoma, enchondroma, osteochondroma, nonossifying fibroma, and Paget disease. Accurate identification of these lesions should be within the scope of most orthopedic surgeons and, because most of these patients will not need surgical treatment, referral to orthopedic oncology will not typically be required.

Key points

- •

Radiography, not MRI or computed tomography, is most useful for diagnosing bone tumors.

- •

Most bone and soft tissue tumors have a characteristic age of presentation and radiographic appearance.

- •

Biopsy is not always required to diagnose many bone and soft tissue tumors.

Introduction

For many practicing orthopedic surgeons, encountering a potential bone tumor in a patient is an unwelcome challenge. Although most lesions are benign, the possibility of missing a malignancy causes understandable anxiety. Biopsy may confirm a suspected benign diagnosis but may be an unnecessary, invasive procedure in many cases, because careful analysis of clinical presentation and imaging findings will suffice for many lesions. Most orthopedic surgeons are also familiar with the caveat that an inappropriately performed biopsy of a musculoskeletal malignancy may alter or harm a patient’s outcome, and should be performed or guided by the treating oncologic surgeon.

Many readily identifiable musculoskeletal lesions have an indolent or self-limited course and do not require treatment. Orthopedics has a built-in advantage in that x-ray, a cheap and readily available test, can often identify the underlying bone biology. Some of the lesions that are identifiable on radiography include fibrous dysplasia, nonossifying fibroma, enchondroma, osteochondroma, Paget disease, and marrow infarction.

Further, several soft tissue lesions can be reliably identified with MRI alone, including lipoma, well-differentiated liposarcoma (atypical lipoma), benign nerve sheath tumors, diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis, fibromatosis (extra-abdominal desmoid tumor), congenital venous malformations (“intramuscular hemangioma”), and periarticular cysts (eg, Baker cysts).

Need for Referral

Several of these lesions are indolent and sufficiently identifiable by clinical and imaging findings that routine referral to orthopedic oncology is not required. Of course, physicians must make the appropriate decision for their patients, taking into account the clinical findings and their own training and diversity of their practice.

Five proposed lesions are as follows:

- 1.

Lipoma

- 2.

Enchondroma

- 3.

Nonossifying fibroma

- 4.

Paget disease

- 5.

Osteochondroma

Introduction

For many practicing orthopedic surgeons, encountering a potential bone tumor in a patient is an unwelcome challenge. Although most lesions are benign, the possibility of missing a malignancy causes understandable anxiety. Biopsy may confirm a suspected benign diagnosis but may be an unnecessary, invasive procedure in many cases, because careful analysis of clinical presentation and imaging findings will suffice for many lesions. Most orthopedic surgeons are also familiar with the caveat that an inappropriately performed biopsy of a musculoskeletal malignancy may alter or harm a patient’s outcome, and should be performed or guided by the treating oncologic surgeon.

Many readily identifiable musculoskeletal lesions have an indolent or self-limited course and do not require treatment. Orthopedics has a built-in advantage in that x-ray, a cheap and readily available test, can often identify the underlying bone biology. Some of the lesions that are identifiable on radiography include fibrous dysplasia, nonossifying fibroma, enchondroma, osteochondroma, Paget disease, and marrow infarction.

Further, several soft tissue lesions can be reliably identified with MRI alone, including lipoma, well-differentiated liposarcoma (atypical lipoma), benign nerve sheath tumors, diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis, fibromatosis (extra-abdominal desmoid tumor), congenital venous malformations (“intramuscular hemangioma”), and periarticular cysts (eg, Baker cysts).

Need for Referral

Several of these lesions are indolent and sufficiently identifiable by clinical and imaging findings that routine referral to orthopedic oncology is not required. Of course, physicians must make the appropriate decision for their patients, taking into account the clinical findings and their own training and diversity of their practice.

Five proposed lesions are as follows:

- 1.

Lipoma

- 2.

Enchondroma

- 3.

Nonossifying fibroma

- 4.

Paget disease

- 5.

Osteochondroma

Lipoma

Clinical Features

Lipoma is the most common neoplasm of the soft tissues. It presents as a slowly enlarging, superficial or deep mass that has often been present for years and is most common in the proximal extremities, upper back, and abdomen. Lipomas do not diminish in size during weight loss, which sometimes leads to their discovery.

Superficial lipomas are distinctive on physical examination, presenting as soft, compressible masses with a doughy consistency. In contrast, deep lipomas may not be compressible because of the constraint of the enveloping muscle. In the absence of appropriate imaging, this may lead to unwarranted concern of a malignancy. Although superficial masses are unlikely to be painful, deep masses can be associated with activity-related symptoms.

Imaging Features

Although MRI is the gold standard for soft tissue masses, musculoskeletal ultrasound can be highly accurate in diagnosing superficial lipomas, which will appear as uniformly hypoechoic masses. When appropriately performed, ultrasound will identify the correct diagnosis for greater than 90% of superficial lipomas.

On computed tomography (CT), lipomas will appear as a homogeneously low-density mass. When density is quantified on CT, lipomas will typically demonstrate negative Hounsfield units, as fat has lower density than water.

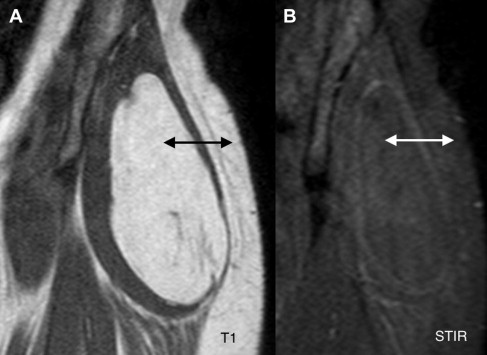

Although ultrasound or CT imaging may suffice for diagnosis, MRI is always definitive. The key observation is that the appearance of the mass will be similar to that of nearby subcutaneous fat in all pulse sequences ( Fig. 1 ). These images should include at least a T1 and either a T2 with fat saturation or an STIR (short tau inversion recovery) sequence. Properly performed T1 images should preferably have a repetition time (TR) of less than 500 ms; values near 1000 ms are closer to proton density–weighted sequences and of less value because they also pick up water signal. Contrast administration is not required.

A special case is subcutaneous lipomas. Even grossly visible and palpable masses may not be evident on MRI, because the fat signal of the lipoma blends in with the surrounding subcutaneous fat. The combination of a visible and palpable subcutaneous mass and the absence of a mass on MRI is effectively diagnostic of a subcutaneous lipoma.

Differential Diagnosis

Although the diagnosis of lipoma, particularly with MRI, is usually straightforward, a few other lesions can have some overlapping features. Luckily, none of these poses a significant danger to the patient, and thus by extension to the diagnosing clinician.

Well-differentiated liposarcoma, despite the name, has effectively no metastatic potential and low risk of recurrence with marginal excision, and is thus treated similar to lipomas. Clinically, it will typically present with more rapid growth than lipoma and is more likely to be deep-seated.

The primary difference on imaging between lipoma and well-differentiated liposarcoma, also sometimes called atypical lipoma in the extremities, is that the latter will have more prominent septations on MRI. These appear as irregular thin lines that are low signal (dark) on T1-weighted sequences and high signal (bright) on T2-weighted sequences ( Fig. 2 ). In one study, experienced observers were able to correctly identify lipomas versus well-differentiated liposarcomas with 75% accuracy based on MRI alone.

Clinicians should also be aware of some common lipoma variants, including spindle-cell lipoma, which is a lipoma with a prominent fibrous component. Sometimes also called fibrolipoma , this is typically found as an extrafascial mass overlying the thoracic and cervical spine, mostly in men. Angiolipoma is a variant often associated with pain. It is more common in the forearm and may actually represent an involuted vascular malformation. In paraspinal regions, angiolipoma can be associated with radicular pain. Hibernoma is a less common variant containing brown fat cells. On MRI, it contains regions with characteristic fat signal but appears more heterogeneous. It is more vascular than normal lipomas and, because it is metabolically active, will demonstrate intense uptake on positron emission tomography. Lipoblastoma is a rare benign lipomatous tumor seen in children; it contains immature fat cells (lipoblasts) and is thought to later evolve into lipoma.

Although not a true variant, some intramuscular lipomas will be infiltrated by traversing muscle fibers, giving a heterogeneous appearance that in some cases can be confused with well-differentiated liposarcoma. However, paying attention to the correspondence between short-axis (axial) and long-axis (coronal) images should show that the heterogeneity in the fat signal is caused by traversing muscle fibers ( Fig. 3 ).

Lipomatosis is a proliferative disorder of subcutaneous fat, and not a true neoplasm. The more common familial variant presents as multiple, soft, and typically painless lumps distributed throughout the trunk and proximal extremities ( Fig. 4 ). It can present as early as adolescence and has an autosomal dominant transmission. Multiple symmetric lipomatosis or Madelung disease is rarer, is found in the neck and face, and is associated or exacerbated by alcohol abuse.

Author’s Recommendation

Once lipoma is diagnosed, it is helpful to reassure the patient that lipomas do not have any malignant potential. Small and asymptomatic lipomas can safely be observed. Liposuction or even steroid injections have been proposed for small superficial lipomas.

Surgical treatment, if undertaken, is directed toward symptom relief and sometimes toward eliminating a large or unsightly mass. Intramuscular lipomas in particular are more likely to cause activity-related discomfort. In these cases, complete but marginal excision is adequate. Often, the lipoma will have a well-formed capsule that helps to define a clear plane between muscle and lipomatous tissue. In other instances, the lipoma will be removed in fragments. Regardless, once completely excised, lipomas rarely recur.

Enchondroma

Clinical Features

Enchondroma is the second most commonly biopsied bone tumor after osteochondroma. It is the most common bone tumor in the hand, representing more than 2 of 3 lesions in one large series. Enchondromas are more common in hands than feet, and very uncommon in the flat bones. Among the long tubular bones, the femur is the most common location, followed by the humerus and tibia.

The most common presentation for an enchondroma is as an incidental finding during evaluation for unrelated musculoskeletal symptoms. However, in the small tubular bones of the hand and feet, enchondromas may present with pain caused by microfracture or, in up to one-third of cases, with a displaced fracture.

Imaging Features

Enchondromas have a characteristic appearance on radiographs, appearing as partially lytic lesions, centrally located in the metaphysis or metadiaphysis. When predominantly lytic, they demonstrate a narrow zone of transition into normal bone, consistent with their indolent nature. More typically, the lesions ( Fig. 5 ) will demonstrate a characteristic chondroid mineralization pattern, consisting of arcs, whorls, and stippling.

In the hands, enchondromas are more commonly located in the proximal portion of the phalanges and the distal portion of the metacarpals, corresponding to the growth plates. Enchondromas in the hand may not show visible mineralization on radiography, and may even show marked expansion and thinning of the cortices, in sharp contrast to the long tubular bones ( Fig. 6 ).

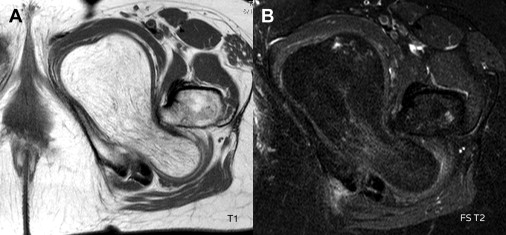

On MRI, high signal predominates on T2 sequences, consistent with the abundant water content of cartilage. Typically, interspersed regions of low T1 and T2 signal are present, corresponding to areas of mineralized cartilage.

The extent of uptake on bone scintigraphy has been proposed to help differentiate between benign and malignant chondroid tumors, with only 21% of benign enchondromas showing more uptake than the anterior iliac spine. In practice, however, scintigraphy rarely adds useful information, because most enchondromas are small, with little if any endosteal involvement, and thus easily identified as benign.

Differential Diagnosis

As the calcification that follows vascular insult to bone can demonstrate a somewhat similar stippling pattern on radiographs to that of chondroid matrix, marrow infarction can be mistaken for enchondroma. Furthermore, both conditions may be discovered in a central metaphyseal location. However, marrow infarction will often present as a longer longitudinal lesion, giving a “smoke up the chimney” appearance ( Fig. 7 ).

The distinction between enchondroma and marrow infarction is more obvious if MRI is obtained, wherein the high water content of cartilage will generate a predominantly high T2 signal, which is not typically seen in marrow infarction. Enchondromas, as is typical with cartilage neoplasms, will also have a lobular growth pattern in contrast to the longitudinal, “serpiginous” pattern seen in marrow infarction. Finally, in the absence of articular surface involvement or pain, the treatment for marrow infarction is simply observation, and therefore mistaking enchondroma for marrow infarction may not be clinically significant.

However, in practice, the clinician is more often vexed in differentiating between an enchondroma and chondrosarcoma. This challenge is often the result of an MRI reading suggesting that an incidentally discovered enchondroma may be a low-grade chondrosarcoma. Although some caution in the face of an unexpected finding is prudent, this is often not a difficult distinction. Features that suggest malignancy include persistent and slowly worsening pain, large size, and deep endosteal scalloping. Overt findings of malignancy include periosteal reaction or cortical breakthrough ( Fig. 8 ). Chondrosarcoma is extremely uncommon in the hands and feet. Conversely, enchondroma should only be diagnosed with caution in chondroid lesions of the flat bones, like the pelvis, scapula, and ribs.