Soft Tissue Pathology of the Ankle

Keywords

• Soft • Tissue • Pathology • Ankle

Derangements of the soft tissues within the ankle joint can be secondary to a wide variety of pathophysiology. They typically involve synovial or fibrocartilaginous tissue and are chronic in nature.1 Patients commonly present with persistent pain, swelling, and limitations on function. Left untreated, many of these conditions can progress to permanent joint degeneration. Fortunately, once diagnosed, they often respond well to current treatment options, with arthroscopic debridement playing a large role.

Traumatic

Approximately 1 million acute ankle injuries occur annually in the United States, with the vast majority of these being diagnosed as lateral ankle sprains.2 Depending on the severity of the trauma and the response of the tissue, sequelae can range from minimal and temporary inflammation to prolonged disability. As many as 15% to 20% of injuries can result in chronic symptoms.3 For patients who have an extended recovery, common soft-tissue pathology includes nonspecific synovitis and secondary impingement lesions.

Synovitis

The interior of the ankle capsule is lined by a synovial membrane, a tissue that functions to provide cushioning and lubrication for the joint. Often during an inversion sprain to the lateral collateral ligaments, some damage will occur to the synovium as well. This injury will result in irritation and inflammation, causing pain and swelling of the membrane. Symptoms can be local or generalized, but are typically limited to the anterolateral aspect of the joint.4 Many times the sensation is vague, and discomfort only occurs with increases in activities.

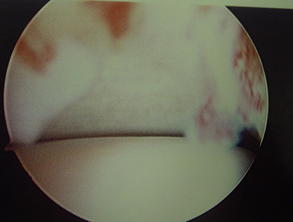

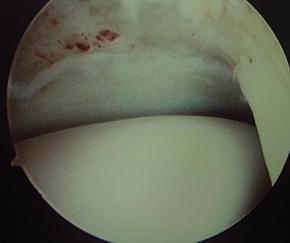

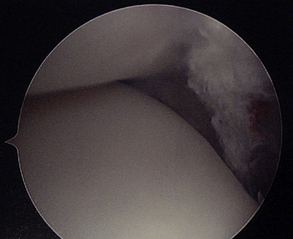

Initial treatment is conservative, with immobilization, physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, and potentially corticosteroid injection, reserving surgery for resistant cases. If symptoms are refractory to these measures, arthroscopic debridement is the next step. Fortunately, nonspecific synovitis typically responds very well to this modality, and recovery time is minimal (Figs. 1 and 2). Radical excision is not necessary, as successful outcomes can be achieved with focus aimed specifically at pathologic tissue. Ferkel and colleagues5 performed limited synovectomies on 31 patients, with 26 reporting good or excellent results. A postoperative regimen of physical therapy may be considered to limit swelling and enhance return of function, and overall the prognosis is good for these patients.

Impingement

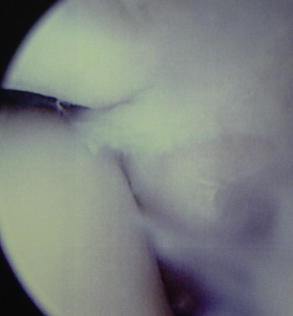

Conditions that cause painful restriction of movement in the ankle joint due to tissue overgrowth are termed impingement syndromes (Fig. 3). In those cases where the limitation of motion is due to soft tissue hypertrophy, several distinct phenomena can be the cause. While the presence of impinging abnormal fibrous tissue in various forms and locations within the ankle joint has been thoroughly reported in the literature, the pathophysiology and certain characteristics of these lesions are subject to debate. However, the general consensus is that antecedent trauma of varying severity is typically associated with their development, usually in the form of a lateral ligament sprain.6

Wolin lesion

A mass of hyalinized connective tissue arising from the anteroinferior portion of the ankle joint was first described by Wolin and colleagues7 in 1950. In their study of 9 patients with chronic anterolateral ankle joint pain and swelling following inversion injuries, a dense mass of white, fibrocartilaginous tissue was noted in the interval between the talus and the fibula upon arthrotomy. Wolin suggested the lesion developed as a result of incomplete resorption of post-traumatic tissue, wherein shear forces between the talus and the fibula molded the scar tissue under pressure into an organized mass. As the presentation of the lesion was similar to that of a meniscus, he labeled it a meniscoid.

Controversy exists in terms of the nomenclature, as different authors have labeled similarly described pathology alternatively as plica syndrome,8 fibrous bands,9 or synovial impingement lesions.10 It is likely that each of these exists on a continuum, with the organized meniscoid lesion being the well-differentiated end product. The nature of the scar tissue in question is also unclear, as traumatic synovitis was postulated by Wolin, whereas other authors endorsed a tear of the anterior talofibular ligament.11

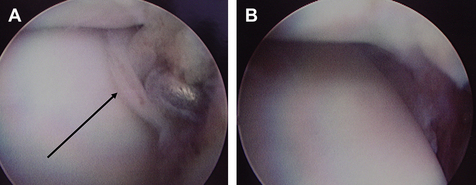

A trial of conservative therapy is not unwarranted with this condition; however, if a true organized meniscoid lesion is present, this is unlikely to be successful in eliminating symptoms. Fortunately, in all reported cases wherein an isolated mass of scar tissue was excised from the anterolateral gutter, patients have experienced significant improvement postoperatively (Fig. 4).

Bassett lesion

A lesion that is close in proximity to the meniscoid but a distinct clinical entity is the pathologic accessory anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL). Bassett and colleagues12 were the first to report an accessory fascicle of the AITFL as the cause of ligamentous impingement in the anterior ankle joint. An anatomic variant, the accessory fascicle, has been identified in anywhere from 21% to 92% of patients (depending on criteria) as a band oriented in parallel to the main ligament but separated from it by a fibrofatty septum.13 The presence of this structure can therefore be considered a normal finding.

This accessory ligament can become pathologic following an inversion ankle injury that involves damage to the AITFL. If subsequent anterolateral hyperlaxity develops that results in anterior extrusion of the talar dome with dorsiflexion, the inferior fascicle of the AITFL will contact the talus with increased pressure and friction. This can often be reflected by the presence of an abraded area of the cartilage of the talus observed during arthroscopy. Bassett’ lesion is thus a problem of abnormal positioning of normal anatomy (Figs. 5 and 6).

Much like Wolin lesion, the diagnosis of Bassett lesion should be considered in patients who have chronic ankle pain in the anterolateral region of the ankle after an inversion injury and have a stable ankle and normal plain radiographs. The main clinical difference between the 2 conditions will be the location of point tenderness, where in the case of Bassett lesion should be the anterolateral aspect of the talar dome and in the AITFL. Also, an audible popping and aggravation of pain with dorsiflexion and eversion have been reported to be more common with Bassett lesion than with other impingement lesions.12

Conservative management may be futile for this condition, as Akseki and colleagues14 demonstrated that a regimen of physical therapy, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and bracing for 3 months failed in all 21 patients they studied. In comparison, resection of the thickened and pathologic ligament was successful in relieving pain in these same patients (as well as those in Bassett’s study), without causing any additional instability of the joint. A point to consider is that patients with less than 2 years of ankle pain before surgery for anterior ankle impingement showed significantly better scores in pain, swelling, ability to work, and engagement in sports postoperatively,15 so prompt diagnosis and excision are key to better outcomes.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree