Tibial Pilon Fractures: Open Reduction Internal Fixation

Joseph Borrelli Jr.

Indications/Contraindications

Intra-articular fractures of the distal tibial articular surface (pilon fractures) represent approximately 1% of all fractures, and approximately 3% to 9% of all tibia fractures (1). Generally, two types of tibial pilon fractures have been recognized. Rotational type fractures usually arise from a relatively low-energy, rotational force, similar to that which may occur during recreational skiing. These fractures typically are spiral in nature and are generally associated with little articular comminution and limited surrounding soft-tissue injury. The more problematic type of pilon fracture is the high-energy, axial compression-type fracture. These fractures typically occur in high-energy motor-vehicle crashes, falls from a considerable height, and crush injuries like those incurred in industrial accidents. This fracture is commonly associated with articular and metaphyseal comminution and significant soft-tissue injury 2. In either case, the fibula may or may not be fractured. It is important that the treating physician recognize the difference between these two fractures types, for although the indications for operative treatment are the same, the timing for definitive treatment, the patient’s prognosis, and the outcome, will differ.

Surgical indications for tibial pilon fractures include the following: (a) articular fracture displacement of ≥2 mm, (b) unstable fractures of the tibial metaphysis, and (c) open pilon fractures. Contraindications to formal open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) include severe soft-tissue injury where blistering and skin necrosis or persistent swelling precludes safe surgical intervention, and severe articular comminution, which would make satisfactory articular reduction and stabilization extremely difficult or impossible. Relative contraindications to formal ORIF include infirmity of the patient; advanced patient age and osteopenia; prior local surgery or previous soft-tissue transfers; advanced, peripheral, vascular disease (associated with a history of smoking, and/or diabetes); and other co-morbidities that would make surgical intervention too risky. Also, patients who would be unable or unwilling to cooperate in postoperative weight bearing restrictions (i.e., those with generalized weakness, dementia, or neurologic deficit) are also felt to have relative contraindications for surgery.

Preoperative Planning

Preoperative planning is essential for a successful outcome following treatment of a pilon fracture. Thorough preoperative planning is dependent upon the surgeon developing a complete understanding of the fracture pattern, surgical approaches, blood supply to the fracture fragments, and awareness of the availability, applicability, and limitations of the various surgical implants. A thorough history and physical examination of the patient and the limb is essential. Particular attention is paid to the condition of the soft tissues in the lower leg and ankle. A detailed neurovascular exam and evaluation of the compartments of the leg must be documented. Fracture blisters are common and may influence the timing and method of treatment.

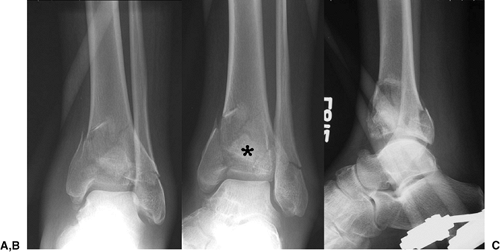

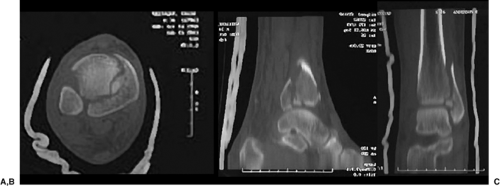

To gain a complete understanding of the fracture pattern, a detailed study of the radiographic images is necessary. Routine radiographic assessment of pilon fractures includes anteroposterior (AP), mortise, and lateral views of the ankle (Fig. 31.1). In case of fracture displacement or shortening, traction radiographs may be extremely helpful. These are often obtained following application of a spanning external fixator. Axial computed tomography (CT) scans are necessary for understanding the fracture pattern in general and the articular injury in particular. The CT scan of the distal tibia and ankle is most helpful when performed after a preliminary reduction and application of the spanning external fixator. Axial, sagittal, and coronal reconstructions of the CT scans are recommended (Fig. 31.2). Plain radiographs of the contralateral ankle can be helpful for preoperative planning as they serve as a template for the fractured side.

The preoperative plan should include a thorough step-by-step description of how the surgery is to be carried out and a diagram of the fractured distal tibia and of the desired final fixation construct. In general, the plan begins with patient positioning, site(s) to be prepared for surgery, a description of the approach(es) to be used, the steps necessary to restore articular congruity, and the restoration of length, alignment, and rotation of the limb. It also includes the creation of a stable fixation construct that will allow early mobilization of the patient and the ankle.

Surgery

Surgery is performed under general or spinal anesthesia. A first-generation cephalosporin is administered and continued for 24 to 48 hours postoperatively. The use of a tourniquet is

left to the discretion of the surgeon. Formal ORIF of displaced pilon fractures should be carried out in two stages to minimize the risk of surgical complications. For each of these two stages, the patient is positioned supine with a padded bump beneath the ipsilateral greater trochanter and hip to help maintain the operative leg in neutral rotation. The first stage, which includes application of a spanning external fixator and internal fixation of the fibula, should be performed within 24 to 36 hours of the fracture, when possible. The fibula is approached through a slightly more posterolateral incision than usual and the fracture is reduced and plated with either a one-third tubular plate (metaphyseal fracture) or a 3.5 limited-contact dynamic-compression (LCDC) plate (diaphyseal fracture). When appropriate for the fracture pattern, the construct should be supplemented with a lag screw placed across the fracture. Occasionally the fibula can be stabilized with a single, partially threaded, cancellous screw placed from distal to proximal within the medullary canal of the fibula as an intramedullary splint. This method is particularly effective when the fracture is transverse and helpful when it is associated with lateral soft-tissue compromise.

left to the discretion of the surgeon. Formal ORIF of displaced pilon fractures should be carried out in two stages to minimize the risk of surgical complications. For each of these two stages, the patient is positioned supine with a padded bump beneath the ipsilateral greater trochanter and hip to help maintain the operative leg in neutral rotation. The first stage, which includes application of a spanning external fixator and internal fixation of the fibula, should be performed within 24 to 36 hours of the fracture, when possible. The fibula is approached through a slightly more posterolateral incision than usual and the fracture is reduced and plated with either a one-third tubular plate (metaphyseal fracture) or a 3.5 limited-contact dynamic-compression (LCDC) plate (diaphyseal fracture). When appropriate for the fracture pattern, the construct should be supplemented with a lag screw placed across the fracture. Occasionally the fibula can be stabilized with a single, partially threaded, cancellous screw placed from distal to proximal within the medullary canal of the fibula as an intramedullary splint. This method is particularly effective when the fracture is transverse and helpful when it is associated with lateral soft-tissue compromise.

Figure 31.2. A. Axial, (B) sagittal, and (C) coronal reconstructions of a CT scan demonstrate clearly the fracture pattern and the presence of an impacted articular fragment. |

The role of the spanning external fixator is to reapproximate the tibial fracture fragments through ligamentotaxis, provide pain relief, prevent further soft-tissue injury, and allow mobilization of the patient (Fig. 31.3). When the fixator is applied, barring any other serious injuries, the patient can be mobilized with crutches and subsequently discharged to home. This treatment strategy is reflected in the term “traveling traction,” which has been used to refer to the use of this simple spanning external fixator.

The spanning external fixator is generally applied with two 16-mm carbon-fiber rods, two 4.5-mm or 5.0-mm half pins, and a 5.0-mm transfixation pin, a multiple pin clamp, and several pin-to-bar clamps (Fig. 31.4). Occasionally, this frame is supplemented with a 4.0-mm half pin placed into the first metatarsal and an additional pin-to-bar and bar-to-bar clamp and short carbon-fiber rod. Using the multipin clamp as a guide, the two half pins are placed in the midsagittal plane of the tibial diaphysis. The Schanz screws should be placed proximal to the zone of injury to avoid the fracture hematoma and the path of subsequent incisions. These Schanz screws should gain purchase in both the anterior and posterior cortices and therefore should be started one-half fingerbreadth medial to the tibial crest. The calcaneal transfixation pin should be placed from medial to lateral through the posterior-plantar aspect of the calcaneal tuberosity. Manual traction is applied on the transfixation pin to restore limb length and reapproximate the fracture fragments while maintaining the talus beneath the tibial plafond. When the limb is brought to length, the carbon fiber rods are attached to the multipin clamp proximally (1 bar medially and 1 bar laterally) and the transfixation pin is added distally. If the talus is unstable beneath the plafond, ORIF of the fibula or modification of the frame will be necessary.

In this situation, where the talus is unstable, modification of the frame includes the placement of a 4.0-mm half pin into the base of the first metatarsal and the attachment of this pin to the medial carbon-fiber rod with a third rod and a bar-to-bar clamp. This pin will improve stability of the talus as well as help avoid the development of an equinus contracture of the ankle, but it is not routinely necessary. It is important when applying this spanning external fixator that the hind foot and mid foot be positioned in neutral or slight valgus alignment.

When the swelling about the ankle has resolved and the soft tissues have recovered, generally 14 to 21 days after injury, it is possible to embark on the second stage, internal fixation of the distal tibia.

A nonsterile tourniquet is typically applied to the proximal thigh, and the leg is prepped and draped in the usual sterile fashion. Although using a tourniquet during the surgery will provide a bloodless field, its use may lead to increased postoperative swelling and should be limited to 2 to 21½ hours at 250 to 300 mmHg. Several approaches to the distal tibia have been described: The anteromedial approach is most consistently used, with the anterolateral

approach used for selected fracture patterns. A direct medial incision to the distal tibia should be avoided at all costs because of the high rate of soft-tissue complications.

approach used for selected fracture patterns. A direct medial incision to the distal tibia should be avoided at all costs because of the high rate of soft-tissue complications.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree