Fig. 5.1

(a) Left shoulder cadaveric dissection with intact anterior rotator interval. (b) Same shoulder as in (a) with CHL reflected superiorly exposing the soft tissue pulley outlet. (c) Same shoulder as in (a) and (b) with closeup look at the outlet: roof = CHL, anterior wall = SGHL reflection, posterior wall = anterior margin of the SST

In an overhead throwing athlete, injury to the pulley can occur during the follow-through phase of throwing in those with improper mechanics. Throwing across the body at a high flexion angle during follow-through causes the SGHL portion of the pulley to come in contact with the anterosuperior glenoid rim, which, in turn, causes the SGHL reflection to fail—either as a frank tear or failure in continuity (Fig. 5.2) [4]. Failure of the SGHL results in a widened outlet that destabilizes the biceps through shoulder range of motion. Biceps instability due to the SGHL injury may produce biceps tendinopathy, which becomes the primary pain generator resulting in a disabled throwing shoulder in this setting [4]. This mechanism of injury was first described in trauma patients as anterosuperior glenohumeral impingement in forward flexion adduction by Werner in 2000 [3].

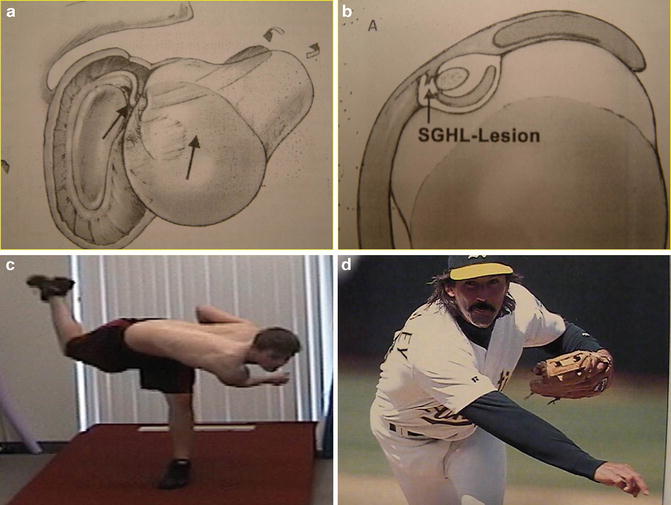

Fig. 5.2

(a) Line drawing illustrating the forward flexion adduction internal rotation mechanism of injury to the SGHL portion of the interval via anterosuperior glenohumeral impingement. (b) Line drawing illustrating the SGHL injury resulting in a widened outlet with biceps outlet instability. (c) Flawed mechanics of throwing across the body in follow-through at a high flexion angle, which puts the SGHL portion of the biceps outlet in jeopardy for injury. (d) Proper mechanics of throwing across the body in follow-through with a lower flexion angle

Clinically, throwers with isolated throwing acquired interval lesions present with very unique history and physical exam findings that are lesion specific [4]. Without exception, these throwers describe anterior superior shoulder pain in the area of the anterior rotator interval which occurs in the late cocking or early acceleration phase of the throwing cycle. Most will point with one finger to this area when asked where their pain is located. Most report pain only with throwing and deny pain with activities of daily living. With regard to the onset of symptoms, approximately 25 % reports a sudden onset of pain with one throw, whereas, about 75 % reports an insidious onset of symptoms. In addition to pain, decreased velocity and loss of command are common complaints. Mechanical symptoms are universally denied.

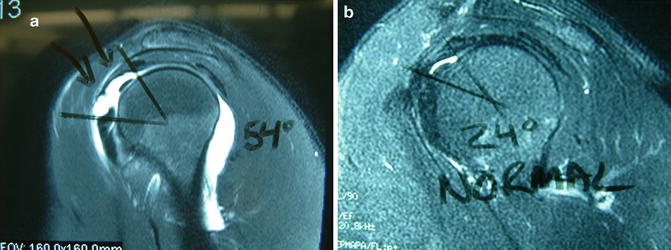

Four unique lesion-specific physical exam findings are usually present in throwers with isolated SGHL pulley lesions: (1) anterior superior pain in the region of the anterior rotator interval in abduction external rotation (ABER) reproducibly reduced by a posterior-directed force on the humerus (Jobe relocation maneuver), (2) pain in the upper bicipital groove to digital pressure, (3) an asymmetric increased sulcus sign in both neutral and external rotation with the arm at the side in the injured shoulder versus the uninjured shoulder, and (4) excessive abduction external rotation (ER) with the scapula stabilized and total motion arc (TMA) by approximately 25° in the injured shoulder versus the uninjured shoulder (Fig. 5.3) [4]. Anterior superior pain in ABER reduced by the Jobe relocation maneuver is explained by the following mechanism. Due to the SGHL injury with a widened outlet, in neutral, the biceps tendon is subluxed anterior-inferior out of the pulley and is free of soft tissue contact. In ABER the tendon relocates and abuts the CHL roof and the SST posterior wall, which produces pain as a result of the synovitis on the dorsum of the inflamed biceps tendon. When the Jobe relocation maneuver is applied in ABER, the tendon subluxes back out of the injured interval anterior-inferiorly into its pain-free position. Digital pain in the upper bicipital groove is caused by synovitis in the groove and biceps tendinitis produced by the destabilizing effect of the SGHL injury. The asymmetric sulcus sign is present due to laxity in the SGHL as well as laxity in the upper middle glenohumeral ligament (MGHL) and coracohumeral ligament (CHL) . The MGHL laxity is the result of laxity in the entire SGHL, including the lower reflection that attaches to and suspends the upper MGHL. The excessive ER and TMA seen in these SGHL-injured shoulders are likely due to the abovementioned laxity in the upper MGHL and CHL . Morgan [4] reported a prospective series of 32 isolated SGHL-injured throwing shoulders compared to an age-matched group of throwing shoulders without intra-articular pathology. In this series, the SGHL-injured group had excessive ER and TMA in their dominant shoulder averaging 27° with a range from 20 to 36° compared to the control group with increased ER and TMA that averaged 6° with a range from 0 to 12°. Morgan [4] first described the sagittal rotator interval angle on MRI arthrogram as a reliable diagnostic imaging tool to determine the presence or absence of anterior rotator interval pathology. On sagittal oblique cuts through the biceps outlet (where only the acromion is seen), the sagittal acromial angle is measured goniometrically by measuring the angle between two lines originating from a point central in the humeral head image: one line to the anterior margin of the SST and one line to the superior margin of the intra-articular subscapularis tendon (Fig. 5.4). In a prospective series of 32 throwing acquired SGHL-injured shoulders, the sagittal rotator interval angle averaged 58° with a range from 44 to 68° [4]. In contrast, an age-matched control group of 31 throwing shoulders with scapular dyskinesis without intra-articular pathology had an average sagittal rotator interval angle of 28° with a range from 22 to 30° [4]. In addition, Nottage independently measured the sagittal rotator interval angle in 240 shoulders without intra-articular pathology [5]. In this series, the normal sagittal rotator interval angle was 30° with a range from 28 to 33°. Sagittal oblique MRI arthrogram images through the outlet also show the subluxed biceps tendon as a biceps “drop-out” sign and the torn SGHL hanging down as a “chandelier” sign (Figs. 5.5 and 5.6).

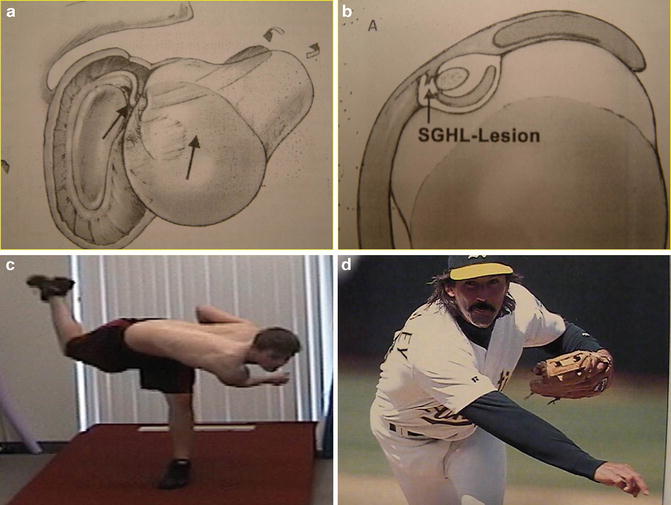

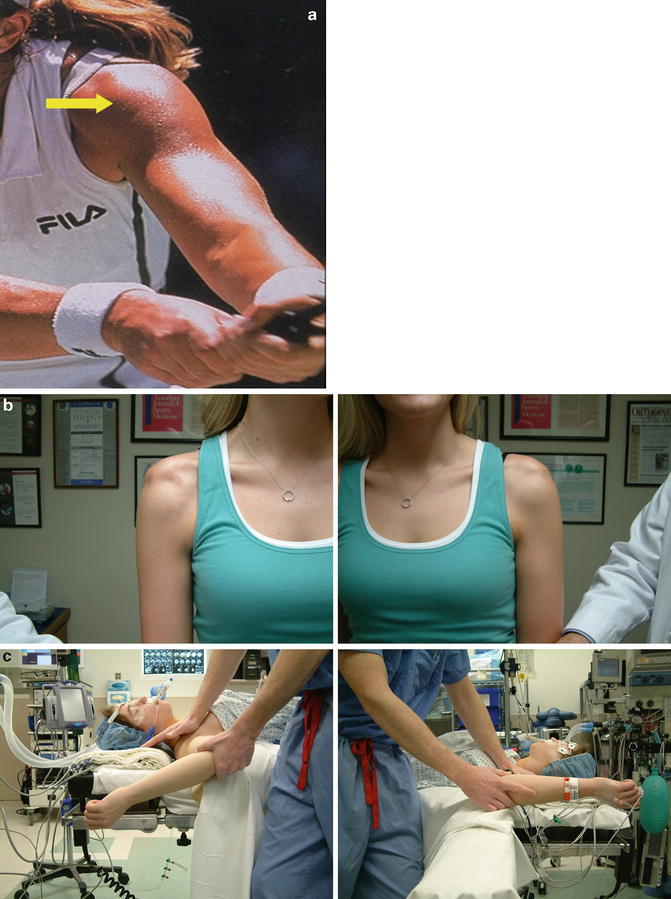

Fig. 5.3

(a) Anterosuperior location of interval lesion pain. (b) An asymmetric sulcus sign in the affected right shoulder. (c) Excessive scapula stabilized ER in the SGHL-injured right shoulder

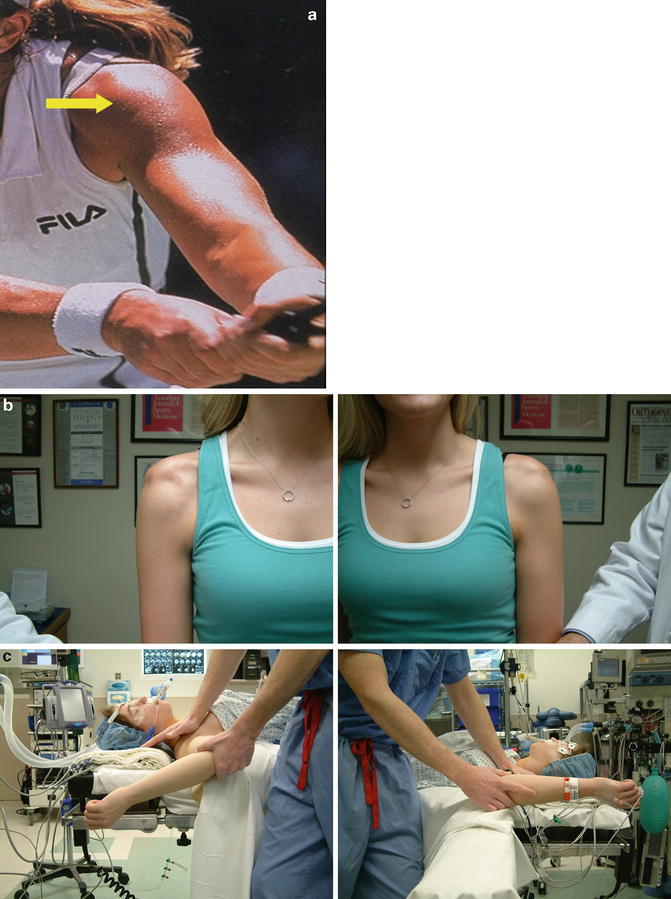

Fig. 5.4

(a) Sagittal oblique MRI arthrogram image of an SGHL-injured shoulder with an enlarged outlet and a pathologic 54° sagittal rotator interval angle. (b) Sagittal oblique MRI arthrogram image of a normal outlet with a 24° sagittal rotator interval angle

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree