CHAPTER 15 Therapeutic massage and bodywork

overview of the practice and evidence of a developing health profession

Introduction

Although therapeutic massage is an ancient healing art, its development as a healthcare profession is quite recent. In seeking to understand therapeutic massage in its current North American incarnation, it is helpful to keep the simultaneously ancient and newborn aspects in mind. Although massage has been an aspect of every form of medicine around the world and through the ages, its development as a profession began late in the 20th century, with great strides having been made in the last few decades (Moyer et al. 2009). It is definitely still ‘under construction’ as a profession, and this reflects real ambivalence among massage therapists about whether the advantages of joining the health professions fold outweigh the costs.

There are a number of challenges to research on massage, and many have written about this. Moyer et al. (2009) convened a working group to address these issues at the 2009 North American Research Conference on Complementary and Integrative Medicine. Among other things, the authors suggest looking to the field of psychotherapy, as they feel that profession and therapeutic massage share some key qualities, including that ‘…both forms of treatment (a) have existed for a considerable time; (b) have scientifically documented effects, but (c) no clear scientific consensus on the mechanisms that underlie their effects; (d) have numerous schools and approaches in which therapists are trained, and which guide their assumptions and selection of specific techniques; and (e) have numerous structural similarities, including typical session length, number of sessions that make up a course of treatment, and the likelihood of repeated, private interpersonal contact between therapist and patient.’

Overview of the profession

Massage is a fast-growing form of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in the US, whether measured in number of clients, practitioners, educational institutions, or dollars spent on it. Between 1990 and 1997 the annual percentage of American adults using massage in a 12-month period increased from 6.9% to 11.1% (Eisenberg et al. 1998). A 2007 survey sponsored by the American Massage Therapy Association (AMTA) estimated that 24% of Americans had received a massage in the previous year. Eisenberg et al. estimated that in 1997 13.5 million Americans visited massage therapists, collectively making 114 million visits, which the AMTA estimated cost between $4 and $6 billion. Recent surveys have suggested the current expenditure to be between $6 and $15 billion. The number of hospitals offering massage increased by 30% between 2003 and 2005 alone (American Hospital Association, 2006).

The AMTA has been a major driver of the professionalization of massage. It is responsible for the first council of massage schools (1982), the creation of the Commission of Massage Therapy Accreditation (1989), initiation of the National Certification Board for Therapeutic Massage and Bodywork (1992), and the founding and ongoing financial support of the Massage Therapy Foundation (1993), which funds research, outreach, and scholarship grants. The Massage Therapy Foundation has also advanced massage research through the creation of a massage research database, the creation of the first research agenda for massage (Kahn 2001) and the creation of a curriculum to bring research education into massage schools (Dryden & Achilles 2003). The AMTA and the Association of Bodywork and Massage Professionals (ABMP) have been the organizations promoting state licensure for massage therapists.

There is wide variety in the education of massage therapists, with over 300 accredited massage schools in the US and an estimated 1200 massage training programs that are not accredited. Many of these programs are quite small. Only 93 schools in the US are accredited by the Commission on Massage Therapy Accreditation (COMTA), the sole accrediting agency in the field recognized by the US Department of Education and authorized to accredit at both institutional and programmatic level. A study of licensed massage therapists in Connecticut and Washington found that they had on average 625 hours of initial training (Cherkin et al. 2002). A recent AMTA survey concurred, reporting that massage therapists have an average of 633 hours of initial training and complete an average 25 hours per year of continuing education, most of this used to acquire new techniques. A small minority of massage schools require a BA for admission.

What is massage?

There are many elements in a massage treatment, and distinguishing their individual contributions to the effect of a treatment is one challenge in the research. In fact, it may be impossible. At the very least we recognize that therapeutic massage includes the impact of compassionate human touch (see Chapter 9) with or without manipulation, the manual therapy or specific manipulation itself, the relationship of therapist and client, the effects of the healing environment, the client’s expectations of the treatment, and the therapist’s intention (see Chapter 11).

There is no definitive taxonomy of therapeutic massage, but there are three projects under way which may take us nearer that goal. One is the Massage Body of Knowledge project, a joint effort of the AMTA and ABMP. The second is an effort of the Best Practices Committee of the Massage Therapy Foundation, which has recently put forth a proposal for a process to create massage therapy guidelines (Grant et al. 2008). The third is a taxonomy drafted by the Massage Therapy Research Consortium, a consortium of massage schools in the US and Canada working to build research capacity within their schools and to create aids for all massage therapy researchers.

Engage the skin, superficial fascia, and subcutaneous fat down to the investing layer of the deep fascia

Engage the skin, superficial fascia, and subcutaneous fat down to the investing layer of the deep fasciaPresence

No matter what technique is used, Andrade and Clifford (2008) stress the role of ‘intelligent touch,’ which they say has three dimensions. The first is attention and concentration, or the therapist’s capacity to focus on the ‘sensory information that they receive primarily, but not exclusively, through their hands.’ The second is the capacity of discrimination, which is described as the therapist’s ‘ability to distinguish fine gradations of sensory information.’ Finally there is identification, which they describe as the therapist’s ability to distinguish between healthy and dysfunctional tissue states and to identify structures and their response to applied forces. These or similar concepts are a part of most massage therapy training programs, and massage trainees receive instructor feedback on their palpatory skill in identifying these tissue states, as well as their skill in applying appropriate levels of pressure and sensing the client’s/body’s response.

In addition to these skills, most massage therapists put much weight on the therapist’s compassionate intention and holistic view of the client as aspects of the treatment – the view that a client’s physical, spiritual, cognitive, and emotional aspects are essentially inseparable from one another, and that all are in some real sense ‘touched’ by the treatment. Whereas to the researcher working within a reductionist framework the results of such care may be a placebo or non-specific effect (see Chapter 11), to the massage therapist they are often central to treatment. Walton (1999) described it this way: ‘By touching a body, we touch every event it has experienced. For a few brief moments we hold all of a client’s stories in our hands. We witness someone’s experience of their own flesh, through some of the most powerful means possible: the contact of our hands, the acceptance of the body without judgment, and the occasional listening ear. With these gestures, we reach across the isolation of the human experience and hold another person’s legend. In massage therapy, we show up and ask, in so many ways, what it is like to be another human being. In doing so, we build a bridge that may heal us both.’

Walton’s view, shared by many massage therapists, probably reflects the influence of the human potential movement on the development of therapeutic massage in the US. At the Esalen Institute, among other places, the intermingling of bodyworkers and psychotherapists led to an exploration of the links between mental and bodily ease and distress, notions of wellness were expanded, and new modalities such as Rolfing, bioenergetics, and Aston Patterning were developed. This deepened exploration of the relationship between human structure and consciousness, which had begun earlier in Europe and which is probably the greatest American contribution to the field (Johnson 1995). It brought attention to the relationship between practitioner and client in creating and maximizing therapeutic effects, an aspect of healing still in need of systematic investigation.

What clients seek

Clients come to massage therapists because of illness and injury, and a desire for wellbeing (Cherkin et al. 2002). In their 1999 survey of licensed massage therapists in Washington and Connecticut, Cherkin et al. examined data from over 2000 visits to massage therapists and found that 19% were for wellness or relaxation, 5% for anxiety or stress, and roughly 63% for musculoskeletal complaints. The musculoskeletal visits were three to one chronic over acute, and within that 63% were 20% back, 17% neck, 8% shoulder, and the remainder were small percentages of varied complaints. This is the most systematic available review of what clients seek from massage treatment.

Review of the literature

Massage for musculoskeletal pain

Given the finding that 63% of visits to massage therapists are primarily for a musculoskeletal complaint (Cherkin et al. 2002), the body of research in this area is strikingly small. Back pain, the most rigorously investigated area, illustrates some of the challenges in massage research. A 2002 review of studies on massage for back pain, for instance, found only eight trials that included a massage arm (Furlan et al. 2002), and in half of these massage was included as a control arm in a study of something else. One of the other studies compared two German forms of ‘massage’ not typically practiced in the United States (Teil massage, and acupressure using a metal roller). Of the remaining three studies, one utilized a combination of massage and selected exercise (Preyde 2000), and the two that used massage alone as the intervention utilized somewhat different protocols (Cherkin et al. 2001, Hernandez-Reif et al. 2001). The lack of comparable and consistent techniques across studies makes reviews challenging and meta-analyses virtually impossible.

With these caveats, the preponderance of evidence is that massage appears effective in reducing pain and restoring function in patients with subacute and chronic nonspecific low back pain, especially when combined with exercises and education (Cherkin et al. 2009, 2001, Furlan et al. 2009, Hernandez-Reif et al. 2001, Preyde 2000). A relatively large (n = 232) and rigorous study (Cherkin et al. 2001) found massage to offer modest cost savings compared to acupuncture or self-help education via book and video, when accounting for a patient’s use of health services for back pain during the year following treatment.

Recent progress in research on massage for musculoskeletal pain

To address this question we conducted a study comparing two distinct massage protocols. Each was designed by leading massage educators to utilize different techniques and presumably different mechanisms of action (Cherkin et al. 2009).

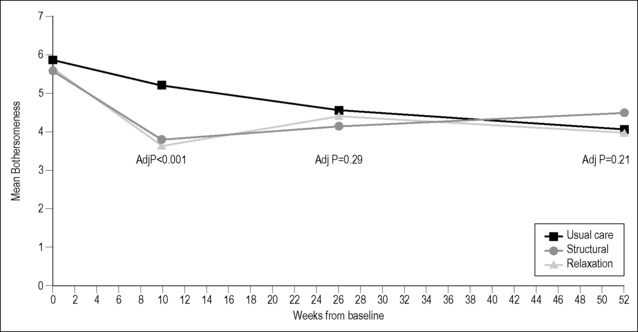

Subjects received a maximum of 10 1-hour massages over a 10-week period. Data were collected at baseline, 10 weeks (end of treatment), 26 weeks, and 52 weeks, just as in the earlier study. As Figures 15.1 and 15.2 show, subjects receiving either form of massage fared significantly better than those in usual care by the end of the treatment period (p < 0.001 for each of the two primary vari-ables), and at that time there was no significant difference between the effects of the two forms of massage. At 26 weeks post baseline (4 weeks after the end of the treatment period) both forms of massage were still showing significantly greater effect than usual care in relation to the Roland Scale of disability (p = 0.003), but there were no significant differences at that point in relation to symptom troublesomeness (p = 0.29). Finally, at the 1-year point the two forms of massage had diverged and, surprisingly – at least to those who value ‘advanced’ technique – the relaxation massage appeared to be more effective than the focused structural massage: significantly better on the Roland Scale (p = 0.04) and slightly, but not significantly, better on the symptom troublesomeness (p = 0.21).

Figure 15.1 Mean Bothersomeness Scores.

Cherkin 2009 – Symptom Bothersomeness Scores (0–10).

(Courtesy of Dan Cherkin; unpublished.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree