Chapter 9 The wrist and hand

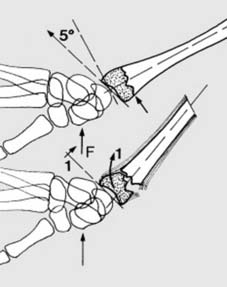

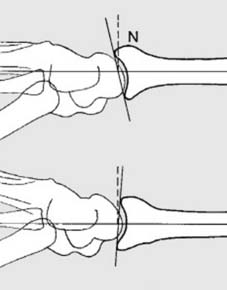

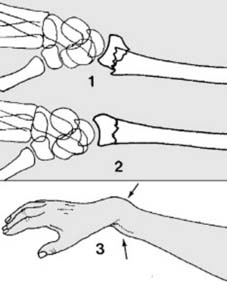

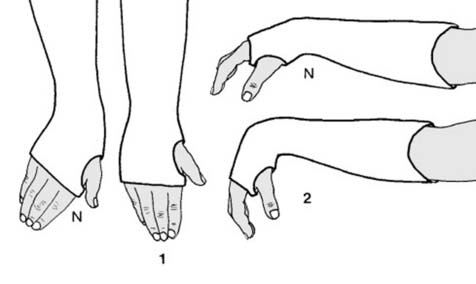

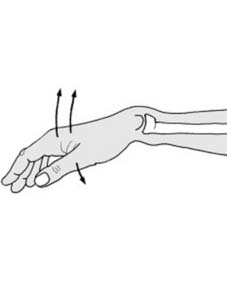

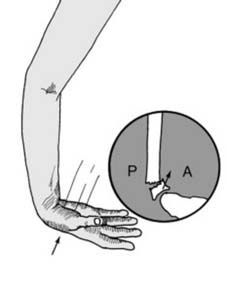

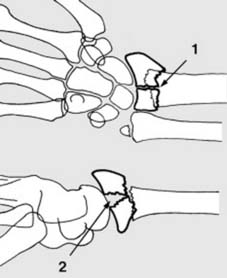

1 Colles fracture: A Colles fracture is a fracture of the radius within 2.5 cm of the wrist (1), with a characteristic deformity if displaced. It is the commonest of all fractures. It is seen mainly in middle-aged and elderly women, and osteoporosis is a frequent contributory factor. It usually results from a fall on the outstretched hand (2), and generally the distal radial fragment remains intact. (See Frame 45 et seq. for those other cases where the radiocarpal joint is involved.)

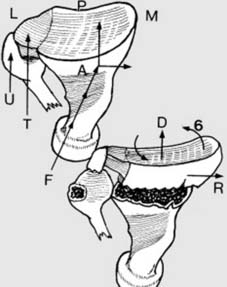

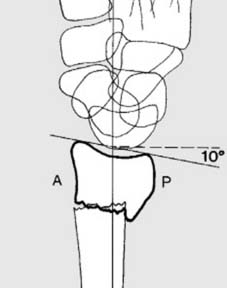

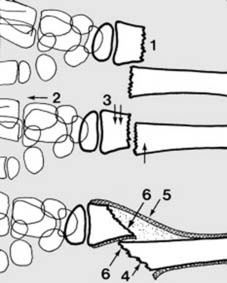

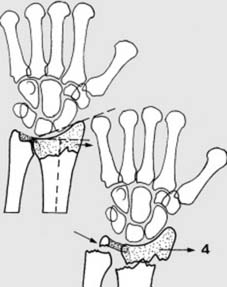

7 Displacements (f): In the AP plane, a small lateral component of the force of impact causes lateral (radial) displacement of the distal fragment (4). The distal fragment is attached to the ulnar styloid by the triangular fibrocartilage, and generally this leads to avulsion of the ulnar styloid. Note that in the AP projection of the normal wrist that the joint surface has a tilt of 22°.

8 Displacements (g): Sometimes the triangular fibrocartilage is torn; in either case there is disruption of the inferior radio-ulnar joint. The distal fragment tilts laterally into ulnar angulation (5) (reducing the tilt to less than 22°) and impacts. The sixth feature is a rotational or torsional deformity (6 in Frame 2), not obvious in either AP or lateral projections.

13 Radiographs (c): In the AP view of the wrist, look for any irregularity in the smooth lateral aspect of the radius.

If there is any doubtful radiographic feature suggesting fracture, return to the patient and confirm whether there is any localised tenderness over the suspect area

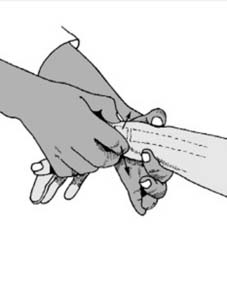

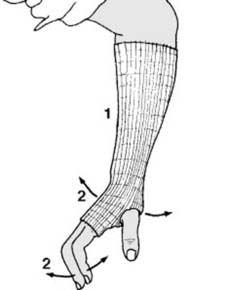

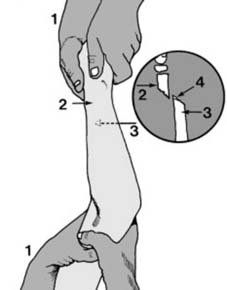

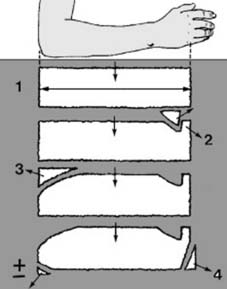

19 Reduction technique (b): Before any manipulation, start by preparing a suitable plaster back slab. The length should equal the distance from the olecranon to the metacarpal heads (1). The width in an adult should be 15 cm (6″), and it should be about eight layers thick. The slab should be trimmed with a tongue (2) for the first web space, a large radial curve to allow elbow flexion (3) and allowance for ulnar deviation (4).

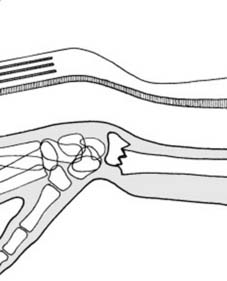

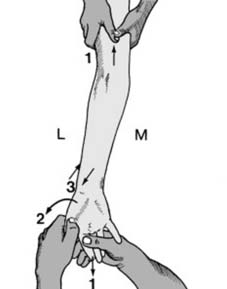

25 Reduction technique (h): Change the grip to allow free application of the plaster (which follows Charnley’s principle of three point fixation). Note that one hand holds the thumb fully extended (1). The other holds three fingers (to avoid ‘cupping’ of the hand) maintaining slight traction (2). The limb should be in full pronation (3), full ulnar deviation at the wrist (4) and slight palmar flexion.

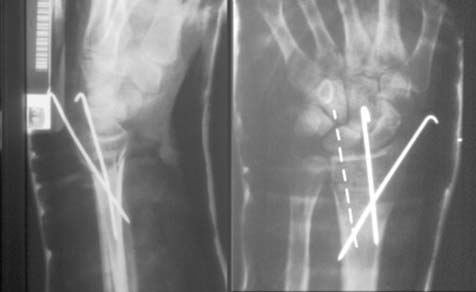

31 Treatment ctd: Check radiographs should be studied. Severe persisting deformity, especially in the AP projection (Illus.) should not be accepted, and remanipulation should be undertaken. If difficulty is anticipated, radiographs may be obtained before discontinuing the anaesthetic. If the position is acceptable, the patient is shown finger exercises and advised regarding normal plaster care.

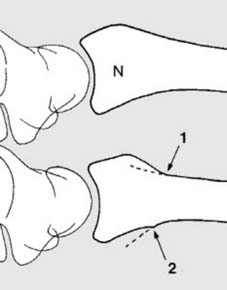

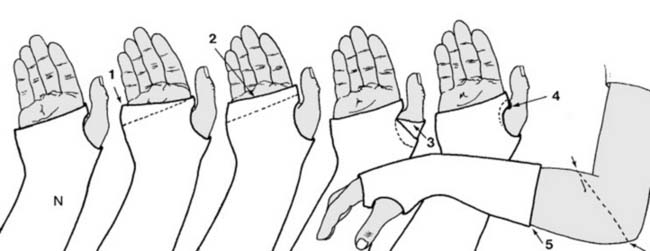

36 Aftercare (e): Plaster faults: Errors in plastering technique should not occur, but nevertheless are often discovered at this stage. The following faults are common: (1) The distal edge of the plaster does not follow the normal oblique line of the MP joints, and movements of the little and sometimes the ring finger are restricted. The plaster should be trimmed to the dotted line. (2) All the MP joints are restricted by the plaster which has been continued beyond the palmar crease. Trim to the dotted line. (3) The thumb is restricted by a few turns of plaster bandage. Again the plaster should be trimmed to permit free movement. (4) The plaster is digging into the skin of the first web and should be trimmed back to the dotted line. (5) The plaster is too short. Support of the fracture is greatly impaired; the plaster should be extended to the olecranon behind, and as far in front as will still permit elbow flexion.

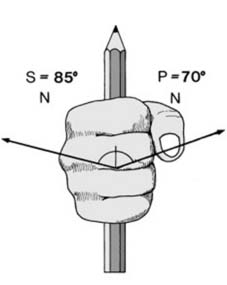

40 Need for rehabilitation (b): 2. Assess the patient’s grip strength by first asking her to squeeze two of your fingers as tightly as possible while you try to withdraw them. Compare one hand with the other. Repeat with a single finger. Marked weakness is an indication for physiotherapy.

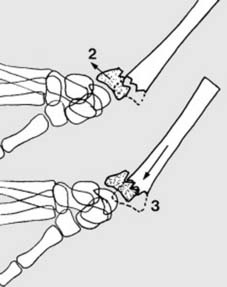

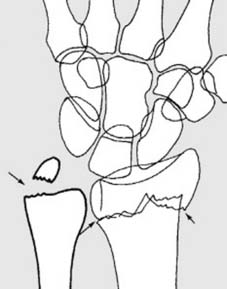

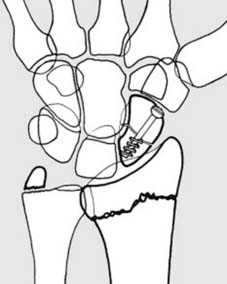

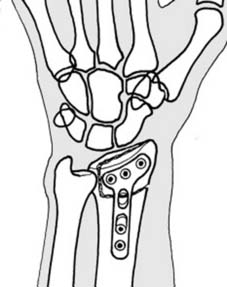

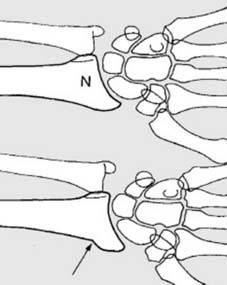

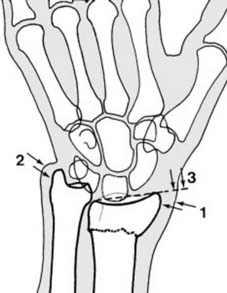

45 Splitting of the radial fragment (a): There may be a small vertical crack through the radial fragment, showing in the AP view (1). In others the fracture may run horizontally, and the scaphoid or lunate may separate the fragments (2). In the young adult, especially where the main fragments are separated and there is no gross fragmentation, internal fixation is indicated. (Barton’s fracture (see Frame 75) is similar, but with an intact posterior radial buttress.)

51 Complications (a): Persistent deformity or mal-union (i): Radial drift of the distal fragment results in prominence of the distal radius (1). Radial tilting and bony absorption at the fracture site lead to relative prominence of the distal ulna (2) and tilting of the plane of the wrist as seen in the AP radiographs (3). These deformities may be symptom free, and surgery on purely cosmetic grounds is seldom indicated.

55 Complications (c): Sudeck’s atrophy/complex regional pain syndrome: This is often detected about the time the patient comes out of plaster. The fingers are swollen and finger flexion is restricted. The hand and wrist are warm, tender and painful. Radiographs show diffuse osteoporosis (Illus.). Treatment. (1) The mainstay of treatment is intensive and prolonged physiotherapy and occupational therapy, but (2) if pain is very severe a further 2-3 weeks rest of the wrist in plaster may give sufficient relief to allow commencement of effective finger movements. (3) If the MP joints are stiff in extension and making no headway, manipulation under general anaesthesia followed by fixation in plaster (MP joints flexed, IP joints extended) for 3 weeks only may be effective in initiating recovery. (4) In severe cases, a sympathetic block may be attempted by infiltration of the stellate ganglion. (See Ch. 5 for a fuller discussion.)

56 Complications (d): Carpal tunnel (median nerve compression) syndrome: Paraesthesiae in the median distribution is the main presenting symptom, but look for sensory and motor involvement. If detected before reduction: (i) Complete lesion: reduce, plaster and re-assess. If no improvement, explore, and divide not only the roof of the carpal tunnel but the antebrachial fascia. (ii) Partial lesion: reduce and apply a cast; if motor symptoms remain, or if symptoms persist for a week, decompress.

62 Related fracture (b): Angled greenstick fracture of the radius: In this type of injury there is both clinical and radiological deformity. Manipulation is required as for a Colles fracture, and the aftercare is similar; the period of plaster fixation may be reduced to 3 or 4 weeks, depending on the age of the child.

68 Related fractures (d): Slipped radial epiphysis: This injury is common in adolescence, and the displaced distal radial epiphysis is usually associated with a small fracture of the metaphysis (Salter-Harris Type 2 injury). Unless displacement is minimal, manipulation followed by plaster fixation (as for a Colles fracture) is indicated. Growth disturbance is rare, but reduction should be carried out promptly (it is often difficult to reduce after 2 days).

74 Smith’s fracture (v): The anterior slab is trimmed (5) and positioned (6) before completion of the forearm part of the cast (7) which may be moulded while setting. The cast is then extended above the elbow. Aftercare: Split if necessary; radiographs at weekly intervals for the first 3 weeks (treat any slipping by remanipulation or moulding); change slack plasters with care. Six weeks’ fixation is usually required, with physiotherapy after removal of the cast.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

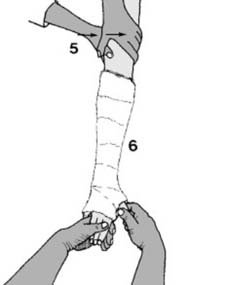

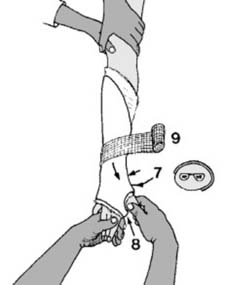

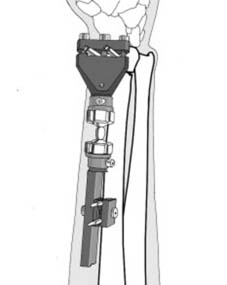

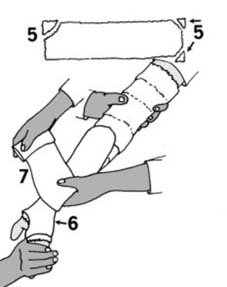

Full access? Get Clinical Tree