4 The variety of reflex points

Are all tender points trigger points?

Distinguishing features of myofascial trigger points

Mechanotransduction, fascial pathways, and endocannabinoid influences – some recent advances

Acupuncture points and their morphology

Acupuncture and applied kinesiology

Alarm points, Associated points, Akabane points

Bennett’s neurovascular reflex points

Connective tissue massage/manipulation

Reflex patterns and areas

Osteopathic physician Eileen DiGiovanna (1991) states: ‘Today many physicians believe there is a relationship among trigger points, acupuncture points and Chapman’s reflexes. Precisely what the relationship may be is unknown.’ She quotes from a prestigious osteopathic pioneer, George Northup (1941), who stated as far back as 1941:

Felix Mann (1983), one of the pioneers of acupuncture in the West, entered the controversy as to the existence, or otherwise, of acupuncture meridians (and indeed acupuncture points). Mann, in an effort to alter the emphasis that traditional acupuncture places on the specific charted positions of points, stated:

This realization is supported by Speransky’s findings from the 1930s, as discussed in Chapter 3.

Distinguishing features of myofascial trigger points

• Active myofascial trigger points produce regional pain complaints and not bodywide pain and tenderness.

• Not all tender points are myofascial trigger points, but all myofascial trigger points are tender.

• Referred tenderness, as well as referred pain, is characteristic of a myofascial trigger point.

• All myofascial trigger points are associated with a taut band.

• Not all taut bands are palpable (requires sufficient palpation skill and accessibility).

• All active myofascial trigger points cause a clinical pain (sensory disturbance) that is familiar to the patient.

• Only an active myofascial trigger point, when compressed, reproduces the clinical sensory symptoms that are familiar to the patient.

• However, a latent myofascial trigger point produces no clinical sensory (pain or numbness) complaint that is familiar to the patient.

Mechanotransduction, fascial pathways, and endocannabinoid influences – some recent advances

It is therefore important to be able to demonstrate evidence that these can:

1. be identified via palpation, and

2. be manipulated/treated manually via stretching or compression – for example – or by tool assisted means (e.g. acupuncture).

Assessment/palpation will be investigated in Chapter 5, while therapeutic approaches will be described in Chapters 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 and 11.

But what are the mechanisms associated with influencing symptoms and tissues at a distance?

Mechanotransduction

Burkholder (2006) notes:

It seems probable that such signalling can be modulated, directed, to achieve positive changes, via appropriate manual methods of treatment (Levin 2000).

Fascial communication

Closely linked to these ideas is an increased awareness of fascial connections that link distant, as well as local, areas of the body (Myers 2008, Huijing & Baan 2001).

Langevin et al (2005) have proposed fascia/connective tissue as a communication system:

Khalsa et al (2005) report that ‘Langevin’s research describes a common feature of manual therapies – the application of mechanical forces to connective tissues. Immediate (viscoelastic and mechanotransduction) and delayed (remodeling) connective tissue effects of these forces may contribute to the mechanism of these therapies.’

Endocannabinoids

In the 1990s a new class of self-generated pain-relieving substances was identified in the body, the endocannabinoids. These substances mimic the pain-relieving and euphoria-generating effects of the use of cannabis, and help to explain its illegal use by many chronically pain-ridden individuals (Degenhardt 2007).

As McPartland & Simons (2007) explain:

Acupuncture points

Soft tissue changes often produce organized discrete areas that act as generators of secondary problems. A repetitive question arises as to whether traditional acupuncture points are in fact the same as trigger points (Fig. 4.1).

When ‘active’, possibly due to reflex factors, these points become even more detectable, as the electrical resistance lowers further. The skin overlying them also alters and becomes hyperalgesic and not difficult to palpate as differing from surrounding skin. Active acupuncture points also become sensitive to pressure and this is of value to the therapist because the finding of sensitive areas during palpation or treatment is of diagnostic importance. Sensitive and painful areas that do not have detectable tissue changes as part of their make-up may well be ‘active’ acupuncture points, or tsubo, which means ‘points on the human body’ in Japanese (Serizawe 1976).

Acupuncture points and their morphology

Pain researchers Wall & Melzack (1989), and others (Travell & Simons 1992, Melzack et al 1977), maintain that there is little, if any, difference between acupuncture points and most trigger points.

Dorsher (2004), carefully compared the location of 255 trigger points, as identified by Travell and Simons, with 747 acupuncture points as identified by the Shanghai College of Traditional Medicine (Chen 1995):

The conclusion was: TPs are essentially a ‘rediscovery’ of the 2000-year-old acupuncture tradition (a subset of acupuncture points). As will be noted below, not all researchers or clinicians agree with these findings (Birch 2008).

The morphology of acupuncture points has been studied, notably by Bosey (1984).

Some of his major conclusions, in summary, are as follows:

• Points are situated in palpable depressions (‘cupules’).

• The skin (epiderm) over the point is a little thinner at the cupule level, under which lies a fibrous cone in which there is frequently found either a neurovascular formation, or simply a cutaneous neurovascular bundle.

• Free nerve endings are noted, and the presence, beneath the point, of Golgi endings and Pacini corpuscles is common.

• Connective tissues lie below at varying depths.

• Fascia and aponeurosis are noted and a passage of vessels and nerves, through the fascia, is very often found under the acupuncture point.

The practice of manipulating the needle in acupuncture imposes a degree of traction on the underlying (muscular) tissue, which imposes stimulation on underlying receptor organs. Fat is also a common factor in the morphology of points, and this, and the connective tissue, is thought to be a key factor in the achievement of the ‘acupuncture sensation’ that accompanies successful treatment. The conclusion reached is that a number of tissues are simultaneously affected needling – a phenomenon confirmed by Langevin (2006), supporting the mechanotransduction mechanisms discussed earlier.

Acupuncture and applied kinesiology

Acupuncture points and trigger points: not all agree that they are the same phenomenon

As outlined earlier, because they spatially occupy the same positions in at least 75% of cases (Wall & Melzack 1989, Dorsher 2004, Dorsher & Fleckenstein 2008) there are strong indications that trigger points are in fact no more than active acupuncture points. Wall & Melzack (1989) have concluded that: ‘trigger points and acupuncture points when used for pain control, though discovered independently and labelled differently, represent the same phenomenon’.

Baldry (1993) does not agree, however, claiming differences in their structural make-up. He states:

Melzack et al (1977) have assumed that acupuncture points represent areas of abnormal physiological activity, producing a continuous low-level input into the central nervous system (CNS). They suggested that this might eventually lead to a combining with noxious stimuli deriving from other structures, innervated by the same segments, to produce an increased awareness of pain and distress. They found it reasonable to assume that trigger points and acupuncture points represented the same phenomenon, having found that the location of trigger points on Western maps, and acupuncture points used commonly in painful conditions, showed a remarkable 75% correlation in position.

Selye has shown us (see Ch. 1) that homeostatic mechanisms are at work, so that any stimulus, if appropriate and not excessive, can result in a beneficial response. In accord with the methods used in treating neurolymphatic and neurovascular points (described elsewhere in this chapter) it is suggested that, to some extent, the ‘feel’ of the tissues be allowed to guide the practitioner. A change (in the sense of a release of tension, or a softening, or a sensing of a gentle pulsation in the tissues) is often an indication of an adequate degree of therapy. In order to sedate what is an overactive point, up to 5 minutes of sustained or intermittent pressure, or rotary contact, may be required.

We have noted previously that many of the different reflex systems have points that seem to be interchangeable, and that many of these are traditional acupuncture points. In terms of local pain, the view of Chifuyu Takeshige (Takeshige 1985), Professor of Physiology at Showa University, is that: ‘The acupuncture point of treatment of muscle pain is the pain-producing muscle itself.’

Respected acupuncture clinicians, such as George Ulett, suggest that ‘acupuncture points are nothing more than time honoured muscle motor points’. Professor C. Chan Gunn, however, finds this too simple an explanation, and states: ‘Calling acupuncture points “motor points” or “myofascial trigger points” is too simple. They are Golgi tendon organs.’ These, and other researchers, are quoted by Stephen Botek, Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry, New York Medical College (Ernst 1983).

Botek (1985) believes that ‘myofascial needling’ is the term of choice to define the type of acupuncture that dispenses with traditional explanations as to the effects of acupuncture. The points utilized in one study were Large Intestine 4 (Hoku) in the web between thumb and the first finger, and Stomach 36 (Tsu san li) below the knee. The study recorded skin temperature of the face, hands and feet. It was found that, compared with a resting period, both manual and electrical stimulation of both points induced a general warming effect. This was immediate in the face (Lewith & Kenyon 1984) and appeared after 10–15 minutes in hands and feet. The temperature increase was notably more marked after manual acupressure than after electrical stimulation. Manual stimulation of these points was shown to be more effective than other forms of stimulation.

Lewith & Kenyon (1984) point to a variety of suggestions having been made as to the mechanisms via which acupuncture, or acupressure, achieves pain-relieving results. These include neurological explanations such as the ‘gate control theory’. This, and variations on this theme, look at the various structures of the CNS and the brain in order to define the precise mechanisms involved in acupuncture’s pain-relieving action.

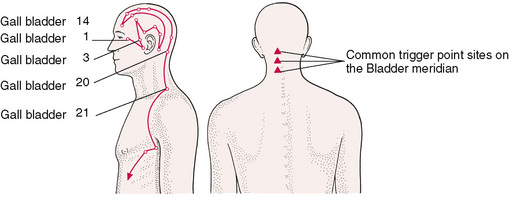

• Head’s zones could be shown to include most acupuncture points, especially the Alarm and Associated points (given below).

• The points noted as being ‘tender’ in appendicitis, such as McBurney’s, Clado’s, Cope’s, Kummel’s, Lavitas’s, are on the Stomach, Spleen and Kidney meridians of traditional acupuncture, and these are used by acupuncturists in treating appendicitis.

• Patients with a gastric ulcer produce tenderness at a site known as Boas’ point, and this is sited precisely on Bladder point 21, which is the Associated point of the Stomach meridian.

• Brewer’s point, in Western medicine, is noted in kidney infection, and this is Bladder point 20, the Associated point for the Spleen (in traditional acupuncture this has a controlling role over water, the element of the kidneys).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree