Abstract

Objective

Our objective is to assess the effect of mechanical and manual intermittent cervical traction on pain, use of analgesics and disability during the recent cervical radiculopathy (CR).

Methods

We made a prospective randomized study including patients sent for rehabilitation between April 2005 and October 2006. Thirty-nine patients were divided into three groups of 13 patients each. A group (A) treated by conventional rehabilitation with manual traction, a group (B) treated with conventional rehabilitation with intermittent mechanical traction and a third group (C) treated with conventional rehabilitation alone. We evaluated cervical pain, radicular pain, disability and the use of analgesics at baseline, at the end and at 1, 3 and 6 months after treatment.

Results

At the end of treatment improving of cervical pain, radicular pain and disability is significantly better in groups A and B compared to group C. The decrease in consumption of analgesics is comparable in the three groups. At 6 months improving of cervical and radicular pain and disability is still significant compared to baseline in both groups A and B. The gain in consumption of analgesics is significant in the three groups: A, B and C.

Conclusion

Manual or mechanical cervical traction appears to be a major contribution in the rehabilitation of CR particularly if it is included in a multimodal approach of rehabilitation.

Résumé

Objectifs

Notre objectif est d’évaluer l’effet de la traction cervicale intermittente manuelle et mécanique sur la douleur, la consommation d’antalgiques et le handicap ressenti au cours de la névralgie cervicobrachiale (NCB) récente.

Patients et méthodes

Nous avons réalisé un travail prospectif randomisé incluant des patients adressés pour rééducation fonctionnelle entre avril 2005 et octobre 2006. Trente-neuf patients ont été répartis en trois groupes de 13 patients chacun. Un groupe A traité par rééducation classique avec des tractions manuelles, un groupe B traité par rééducation classique avec traction mécanique intermittente et un troisième groupe C traité par rééducation classique seule. Nous avons évalué la douleur cervicale et radiculaire, le handicap ressenti et la consommation d’antalgiques avant rééducation et à la fin du traitement à un, à trois et à six mois.

Résultats

À la fin du traitement, l’amélioration de la douleur cervicale et radiculaire et du handicap ressenti est significativement meilleure dans les groupes A et B par rapport au groupe C. La diminution de la consommation d’antalgiques est comparable dans les trois groupes. À six mois de recul, le gain en douleur cervicale et radiculaire et en handicap est toujours significatif par rapport au bilan initial dans les deux groupes A et B. Le gain en consommation d’antalgiques est significatif dans les trois groupes : A, B et C.

Conclusion

La traction cervicale manuelle ou mécanique paraît être d’un grand apport dans la rééducation de la NCB ressente particulièrement si elle est incluse dans une approche rééducative multimodale.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Cervical radiculopathy (CR) can be defined as metameric neck pain, which radiates to the arms. It is a common condition, with an annual incidence of around 83 per 100,000 and an increasing prevalence in the 5th decade of life (203 per 100,000) .

The most common aetiology (in 70 to 75% of cases) is foramenal compression of the spinal nerve. This can be due to one or several of many factors, including reduction in disc height and anterior and posterior degenerative changes of the uncovertebral and zygapophyseal joints, respectively .

Unlike lumbar spine problems, a herniated disc (HD) only accounts for 20 to 25% of cases . Several interventional strategies are used in the management of CR and range from conservative approaches (including physical treatment) to surgery.

In 75% of cases, treatment is conservative and is based on rehabilitation . The rehabilitation programs are generally multifaceted and involve several physical methods, none of which have guaranteed efficacy. Cervical traction (as used in the treatment of post-traumatic neck pain ) is also frequently employed in CR .

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the effect of intermittent manual or mechanical cervical traction on pain, analgesic consumption and self-perceived disability by patients having recently developed CR.

1.2

Patients and methods

1.2.1

Patients

The study population consisted of CR patients referred for rehabilitation treatment. The inclusion criteria were recent CR (i.e. onset within the previous 3 months), involvement of spinal nerve with HD and/or intervertebral disc degeneration confirmed by imaging (computed tomography [CT] and/or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) and concordant radiographic and clinical results. The exclusion criteria were a history of surgery or bone-ligament damage to the cervical spine, shoulder disease (rotator cuff syndrome, capsulitis, acromioclavicular arthropathy, shoulder instability or inflammatory arthritis) or carpal tunnel syndrome, ongoing or recent rehabilitation for the current CR and the worsening of pain or intolerance in a manual cervical traction test performed by the clinician during the first consultation. Patients were referred by rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons and neurologists at Monastir University Hospital (Monastir, Tunisia) and medical practitioners in the surrounding region.

1.3

Methods

This was a prospective randomized study performed over the period from April 2005 to October 2006. We identified 51 cases of CR; after the exclusion of 12 patients, 39 were successively included and randomly assigned (using a randomization list) to one of three groups (A, B and C). In group A, treatment consisted of a “standard” rehabilitation programme involving physical pain relief methods (ultrasound, infrared and massage), cervical spine mobilisation and muscle strengthening via isometric contraction of flexor and extensor muscles, followed by stretching exercises and self-expansion for the spinal muscles.

Manual, intermittent cervical traction (20 20-second tractions, a 10-second inter-traction rest period) were performed by designated physiotherapists ( Fig. 1 ). A force of around 6 kg was applied; this was calculated using a mechanical dynamometer and corresponded to the force that the physiotherapist could exert for 20 successive 20-second repetitions without experiencing major fatigue. The load was reviewed and recorded at the beginning of each manual traction session. In group B, “standard” rehabilitation was combined with mechanical traction in the supine position with a weight-bearing pulley system ( Fig. 2 ). Each session comprised two 25-minute tractions, with a 10-minute rest interval. The weight was gradually increased from five to 12 kg. During the traction, the neck was maintained in the most pain-free position (as determined in the manual traction test at the first consultation). Patients in group C received 12 sessions (three per week) of “standard” rehabilitation alone, i.e., in the absence of any traction. Patients were randomly assigned to one of two physiotherapists because it was impractical to assign all patients to a single practitioner. Examinations were performed at the end of the treatment programme and then 1, 3 and 6 months afterwards by a doctor who was blinded to the patients’ treatment group ( Fig. 3 ).

We evaluated cervical pain, radicular pain and self-perceived disability on visual analogue scales (VASs). Analgesic drug consumption was calculated by averaging the daily number of tablets consumed during the week preceding the assessment for each WHO analgesic drug grade.

1.3.1

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS.10 software. The Kruskal-Wallis test was used for comparisons between the three study groups.

The Wilcoxon test was used to evaluate post-rehabilitation changes in the overall study population and in each of the three groups. Lastly, Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to identify correlations between the parameters studied. The significance threshold was set to p < 0.05 for all tests.

1.4

Results

1.4.1

Characteristics of the study population

We excluded 12 patients due to a history of shoulder diseases (two cases of rotator cuff syndrome, one case of capsulitis and one case of acromioclavicular arthritis), carpal tunnel syndrome (two cases), rehabilitative treatment underway in another clinic (one case) and intolerance in the manual cervical traction test (five cases). The aetiologies of the CR in our study population ( n = 39) were as follows: a HD in 11 cases (28.2%), a degenerative intervertebral disc in 17 cases (43.6%) and osteoarthritis of the uncovertebral joints in 11 cases (28.2%).

Traction was carried out in an intermediate position in 13 cases, in slight flexion in ten cases and in slight extension in three cases. We noted transient side effects (muscle pain) after mechanical traction (group B) in one patient at the start of the course of treatment. These effects were treated with a 5-day course of analgesics and muscle-relaxant drugs. No side effects were noted in the other two groups. None of the patients was lost to follow-up. The study population includes 39 patients (nine men and 30 women; mean age: 41.6 ± 8 years). Twenty patients (51.3%) were shift workers. Exposure to microtrauma (mechanical vibration or heavy labour) was present in 12 patients (30.7%). There was no history of cervical trauma. The most affected nerve roots were C6 (in 20 cases) and C5 (in ten cases) ( Table 1 ).

| Group A n = 13 | Group B n = 13 | Group C n = 13 | p | Overall study population n = 39 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 42.08 ± 11.8 | 38.54 ± 3.6 | 44.23 ± 4.5 | 0.173 | 41.62 ± 7.8 | |

| Gender | Male | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0.648 | 9 |

| Female | 9 | 10 | 11 | 30 | ||

| Nerve root | C5 | 2 | 6 | 2 | 0.359 | 10 |

| C6 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 20 | ||

| C7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||

| C8 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | ||

| Work | Posted | 6 | 8 | 6 | 0.880 | 20 |

| Microtrauma | 5 | 3 | 4 | 12 | ||

| Unemployed | 2 | 2 | 3 | 7 | ||

| Neck pain (VAS) | 58.2 ± 24.4 | 58.3 ± 23.7 | 53.62 ± 15 | 0.92 | 56.7 ± 21 | |

| Radicular pain (VAS) | 59.2 ± 23.5 | 66 ± 26.1 | 60.4 ± 20.6 | 0.6 | 61.9 ± 23.1 | |

| Self-perceived disability (VAS) | 66.4 ± 19.8 | 48.15 ± 26.2 | 35.5 ± 26.8 | 0.018 | 50.05 ± 27.01 | |

| Analgesic consumption (tablets/day) | 3.07 ± 1.3 | 3.38 ± 1.7 | 3.34 ± 1.8 | 0.87 | 3.27 ± 1.6 |

There were 13 patients in each group (A, B and C). There were no statistically significant differences between the three groups in terms of epidemiological characteristics and clinical parameters at the beginning of the study, except for self-perceived disability (which was felt more keenly in group A) ( Table 1 ).

1.4.2

Change over time in the study parameters in the study population

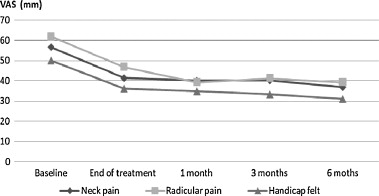

Cervical & radicular pain and self-perceived disability were significantly relieved at the end of the rehabilitation programme ( p < 0.0001, p < 0.0001 and p = 0.001, respectively). Subjective disability decreased further at 1 month post-treatment and continued to decrease until 6 months. A reduction in neck and radicular pain was observed at a month and maintained up to 6 months ( Fig. 4 ).

1.4.3

Description of study parameters at the end of the rehabilitation programme in the three groups

1.4.3.1

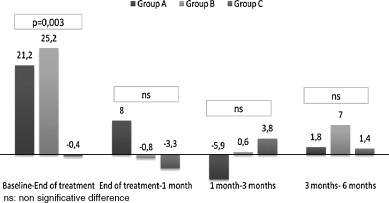

Neck pain

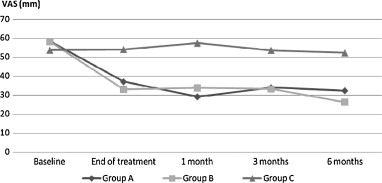

Neck pain was significantly relieved at the end of the rehabilitation programme in groups A and B ( p = 0.009 and p < 0.0001). This contrasted with the situation in group C, in which the change was not significant ( p = 0.23) ( Fig. 5 ).

1.4.3.2

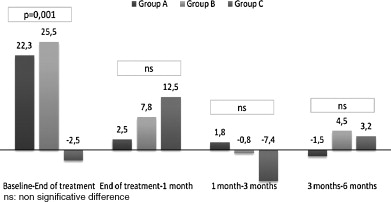

Radicular pain

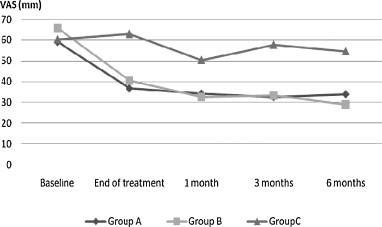

Radicular pain was significantly relieved at the end of the rehabilitation programme in groups A and B ( p = 0.008 and p < 0.0001). In group C, there was a slight but insignificant change at the end of the treatment programme ( p = 0.51) ( Fig. 6 ).

1.4.3.3

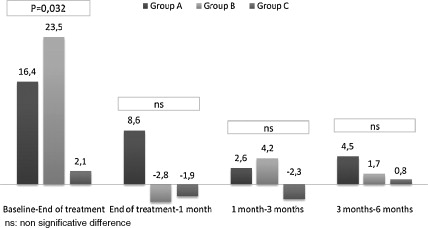

Self-perceived disability

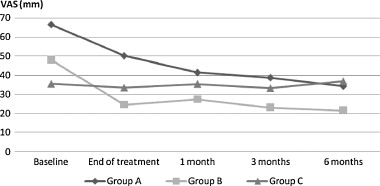

Self-perceived disability was significantly reduced at the end of the programme in groups A and B ( p = 0.044 and p < 0.0001, respectively). In group C, the improvement was not significant ( p = 0.67) ( Fig. 7 ).

1.4.3.4

Analgesic consumption

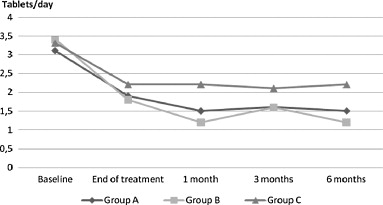

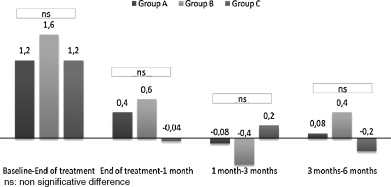

Analgesic consumption fell significantly in groups A, B and C ( p = 0.021, p < 0.0001 and p = 0.012, respectively) ( Fig. 8 ). At the end of the rehabilitation programme, the three groups did not differ significantly in terms of the patient distribution within the analgesic grades ( p = 0.13) ( Table 2 ).

| Baseline | End of treatment | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WHO grade for analgesia | I | II | I | II | I | II | I | II | I | II |

| Group A | 10 | 3 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 11 | 2 | 11 | 2 |

| Group B | 5 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 2 |

| Group C | 7 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 10 |

| p | 0.13 | 0.44 | 0.23 | 0.054 | 0.001 | |||||

| Overall study population | 22 | 17 | 26 | 13 | 27 | 12 | 24 | 15 | 25 | 14 |

1.4.4

Description of study parameters over the 6-month follow-up period and for the three study groups

1.4.4.1

Neck pain

In group A (manual cervical traction), a reduction in neck pain was noted at 1 month but did not improve further at 3 and 6 months ( Fig. 5 ). At 6 months, the difference was still significant, compared with the initial assessment ( p = 0.002). In group B (mechanical traction), the improvement in neck pain relief was stable from the end of the treatment programme until 3 months, with a non-significant improvement at 6 months. At 6 months, the difference was highly significant compared with the initial assessment ( p < 0.0001). In group C (without traction), there were no significant changes in neck pain (compared with the baseline) during or after treatment ( p = 0.70) for the pain at 6 months, compared with the initial assessment. Hence, neck pain was significantly reduced at the end of the treatment programme in groups A and B, compared with group C ( p = 0.003). At subsequent time points, the difference did not increase further by a significant amount ( Fig. 9 ).

1.4.4.2

Radicular pain

In group A, radicular pain fell until the 3rd month and then showed a non-significant increase at 6 months ( Fig. 6 ). At 6 months, the difference was significant when compared with baseline ( p = 0.001). In group B, the change over time was marked by continuous improvement until 6 months post-treatment; the difference at this last time point was significant, compared with the initial assessment ( p = 0.026). In group C, the pain rating rose and fell over the measurement period, with an increase at the end of the treatment programme, a decrease at 1 month and the increases at 3 and 6 months. At 6 months, the improvement was not significant when compared with the initial assessment ( p = 0.14). At the end of the treatment programme, radicular pain relief was significantly greater in groups A and B than in group C ( p = 0.001). At subsequent time points, the difference did not increase further by a significant amount ( Fig. 10 ).

1.4.4.2.1

Self-perceived disability

In groups A and B, perceived disability fell continuously until the 6th month ( Fig. 7 ). At 6 months, the difference was significant, compared with the initial assessment in group A ( p < 0.0001) and B ( p = 0.001). In group C, the perceived disability was slightly lower at the end of the treatment programme and then increased until the 6th month. At 6 months, the difference was not significant when compared with the initial assessment ( p = 0.75). At the end of the treatment programme, the reduction in perceived disability was significantly greater in groups A and B, compared with group C ( p = 0.032). At the following controls, the difference was not significant ( Fig. 11 ).

1.4.4.2.2

Analgesic consumption

In groups A, B and C, changes in analgesic consumption were characterized by a significant decrease at 1 month, with no further change until 6 months ( Fig. 8 ). At this last time point, the difference was significant, compared with the initial consumption ( p < 0.0001 for groups A and B and p = 0.003 for group C). The three groups did not significantly differ in terms of consumption of analgesics for any of the time points ( Fig. 12 ). The groups’ distributions in terms of the analgesic grade were similar at all the time points other than 6 months, at which time patients in group C were significantly more likely ( p = 0.001) to use grade II analgesics than patients in groups A and B ( Table 2 ).

1.4.4.3

Correlation analysis

At 6 months, the decrease in perceived disability was correlated with the decrease in neck pain ( p < 0.05). The decrease in neck pain was also correlated with the decrease in radicular pain ( p < 0.01). It is clear that the more intense the neck and radicular pain and the greater the perceived disability and analgesic consumption at baseline, the greater the improvement at 6 months for each of these parameters ( p < 0.01).

1.5

Discussion

The frequencies of the various CR aetiologies in the study population were similar to data reported in the literature . Degenerative phenomena affecting the intervertebral disc and the uncovertebral joint were more common than HD.

The effect of cervical traction (especially in the long term) is subject to debate. Some authors suggest that the technique is less effective in chronic CR (i.e. a history of CR of over 3 months) . Our work shows a positive impact of combining intermittent mechanical or manual cervical traction with a “standard” rehabilitation program for recent CR. This effect was observed for neck and radicular pain and self-perceived disability (although mainly at the end of the treatment programme). The effect of traction on analgesic intake was smaller and did not differ significantly from that seen with standard rehabilitation. In contrast, patients in the standard rehabilitation group consumed significantly more grade II analgesics at 6 months than either of the traction groups. It is important to note that tolerance of a manual cervical traction test was one of our inclusion criteria.

In the literature, several modes of traction have been evaluated for the treatment of neck and radicular pain resulting from cervical spondylosis or HD. Several authors report favourable results. Zylbergold and Piper demonstrated the contribution of intermittent cervical traction to the treatment of cervical diseases in terms of pain and recovery of spinal mobility (flexion and rotation). A three-week protocol with daily, vertical, intermittent cervical traction, combined with the wearing of a cervical collar and administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and muscle-relaxants, demonstrated its effectiveness in recent CR (onset within the preceding 2 weeks) in young patients with a cervical HD larger than 4 mm . However, the latter study can be criticized in view of the small number of patients ( n = 4) and the lack of a control group. It appears that this type of recent CR is more responsive to cervical traction. Indeed, it is known that a cellular mechanism is involved in the regression of HDs when the latter are exposed to the vascular environment of the epidural space; however, large HDs are absorbed more slowly and respond better to traction treatment, especially when initiated early .

A combination of cervical traction and posture correction exercises has been applied to patients with cervical spondylosis. The resulting clinical improvement was significant and similar to that obtained by posture correction exercises and NSAID treatment (borderline superiority, according to the authors: p = 0.06) . The retrospective analysis by Swezey et al. demonstrated the efficacy of vertical intermittent cervical traction in the sitting position on neck and radicular pain in grade I to III spondylosis (according to the Quebec Task Force classification), with a 81% reduction in symptoms. The duration of the twice-daily traction sessions was 5 minutes. This study also lacked a control group. Conservative treatment with a programme of physical exercise, cervical traction, patient education and administration of oral NSAIDs led to effective treatment in 24 out of 26 patients with CR due to HD. One year later, patient satisfaction remained high and most subjects had resumed their previous activities . However, in the absence of a control group and considering the high number of types of treatments given, it is difficult to ascribe these results to cervical traction.

In the study by Cleland et al. , cervical manipulation and strengthening exercises for the scapulothoracic muscles and the deep flexor muscles in the neck were combined with cervical traction in the treatment of 11 consecutive patients referred for rehabilitation of CR. The authors noted that after an average of seven sessions, ten of the 11 patients showed significant improvements in terms of pain and function at the end of the treatment programme and 6 months later. In a controlled pilot study , cervical weightbath traction (combined with the McKenzie exercises and electrotherapy) was found to be of great value in CR, when compared with exercises and electrotherapy alone. Pain, spinal mobility, function and quality of life parameters were improved at the end of a 15-session treatment protocol and 3 months later. The authors suggested the use of cervical weightbath traction in cases of radicular pain caused by disc protrusion, an HD (in the absence of motor impairment) or cervical spondylosis. In a randomized, controlled study, Joghataei et al. demonstrated that intermittent cervical traction in the supine position resulted in an immediate, short-term improvement in gripping strength (after 3 weeks) in the case of unilateral C7 CR. However, they did not observed mid-term any superiority of this technique relative to conventional rehabilitative treatment. This early effect of spinal traction has been reported in radiographic studies showing a reduction in the size of the HD under traction; this is probably related to the creation of negative pressure in the intervertebral disc . In addition, Hattori et al. have shown that vertical intermittent cervical traction in the sitting position with 15 degrees of cervical spine flexion led to pain relief and improved nerve conduction in spondylotic myelopathy and, in particular, CR. This effect may be related to improvement in the blood supply to nerve structures . Lecocq’s literature review stated that cervical traction has several different modes of action, with a very small increase in the intervertebral space (a few tenths of a millimetre) and a reduction in intradisc pressure, with a possible HD suction effect. The HD can also be pushed back by tension in the posterior longitudinal ligament. In terms of the muscles, the effect of cervical traction is characterized by stabilization of (or even an increase in) activity of the trapezius muscle during the first 3 to 6 minutes. The inhibitory “gate control” effect on nociceptive influx transmission requires experimental confirmation. Furthermore, placebo and psychological effects must be considered when analysing the effect of cervical traction. In view of these findings, we can put forward several anatomical and physiological explanations for the improvement of our patients in group B (mechanical traction). However, in group A (manual traction), psychological and placebo effects probably had a more important role.

The effect of traction on the intervertebral space (with varying cervical spine postures) has been evaluated by several authors. Wong et al. noted that the anterior and posterior intervertebral spaces were increased by traction when in a neutral position and with 30° of flexion. The increase in intervertebral space especially occurred in the C4-C5 disc (12%) in the neutral position and in the C2-C3 disc with 30° of flexion. The posterior intervertebral space mainly increased near the C6-C7 disc (37%) in the neutral position and the C6-C7 (20%) and C5-C6 (19%) discs with 30° of flexion. In the study by Hseuh et al. , the greatest enlargement of the posterior intervertebral space was noted with 30° of flexion for the C4-C5 and C5-C6 discs and with 35° of flexion for the C6-C7 and C7-T1 discs. This effect was greater with a weight between 15 and 18 kg but use of the latter resulted in neck pain after traction. Vaughn et al. used cervical traction in 20 volunteers with 0° and 30° of cervical spine flexion. They noted a significantly greater increase in the anterior intervertebral space for all cervical spine segments with 0° of flexion than with 30° of flexion. The increase in the posterior intervertebral space was also significant, although the difference between the 0° and 30° of flexion positions was not statistically significant. In our series, the cervical spine was in a neutral or slightly extended in 16 of the 26 patients (61.5%) being treated with manual or mechanical traction. Bearing in mind the above-mentioned literature data, we believe that cervical spine traction in the flexion position does not have a greater effect on the posterior intervertebral space and does not provide superior analgesic efficacy.

The CT study by Sari et al. confirmed the biomechanical effect of traction on the cervical spine from C2 to C7, with an elongation of 1.39 mm, a reduction in disc protrusion and an increase in medullar canal surface area of 11.21 mm 2 . MRI has been used to assess the effect of cervical traction on the HD in flexion posture and showed complete resolution or significant reduction of the disc protrusion in 72% of cases with a load of 13.6 kg (30 pounds) . Liu et al. also used MRI to assess the effect of traction on the neural foramen between the 2nd and 7th cervical vertebrae. This was performed in the supine position with a neutral cervical spine posture and led to an increase in the height of the foramen (averaging 3.75, 8.67 and 10.43% for consecutive weights of 5, 10 and 15 kg). The increase in the foramen surface area averaged 5.81, 16.56 and 18.9% for the same series of loads. The authors did not find a significant difference between the 10 and 15 kg loads in terms of foramen height and surface area.

In the present study, manual traction below 6 kg gave similar results to mechanical traction with up to 12 kg. This does not confirm the mechanical effect of manual traction (at least on the ligaments and joint structures) but emphasizes the value of its effect on muscle structures in recent CR. The reduction in pain from muscle structures may explain the decrease in analgesic consumption, which was similar in the three study groups. The contribution of muscle structures almost certainly influenced the tolerance of the manual traction test performed during the first physical examination and thus the inclusion of patients in our study. Given the variability in the results of studies assessing the effect of rehabilitation and the absence of a unanimous consensus on the treatment of CR, Cleland et al. attempted to identify factors that were predictive of a good short-term outcome for physical treatment in CR. These authors identified eight factors: three collected at the interview (age < 54 years, non-dominant arm pain and the lack of pain when looking downwards), one factor obtained during the physical examination (neck flexion > 30°) and four factors related to the physical methods used (mechanical cervical traction, dorsal spine manipulation, no soft tissue mobilization and a multimodal approach). The combination of the first three factors with the multimodal approach involving cervical traction, manipulation and strengthening the deep neck flexors was likely to be effective in 90% of cases. Given the difficulty of finding a standard rehabilitation protocol that is effective in CR, the use of a multimodal approach involving manual or mechanical cervical traction seems to be of value. We recommend the application of criteria for selecting patients for intermittent cervical traction; in our opinion, these should include a history of disease of less than 3 months, tolerance of the cervical traction test and choice of the cervical spine posture – criteria that have to be validated before prescribing this rehabilitation protocol. Lastly, we note that the lack of patient blinding in our study is a potential source of methodological bias, since patients from group C knew that they would not receive traction therapy.

1.6

Conclusion

Treatment of CR is primarily conservative and involves a multimodal rehabilitation approach. Intermittent cervical traction plays an important role when the indication is unambiguous . A disease history below 3 months, good tolerance of the manual traction test and correct choice of the posture of the cervical spine are factors that increasing the likelihood of a good outcome. Chronic CR is a poor indication for intermittent cervical traction. In cases of refractory radicular pain, a progressive neurological deficit or spondylotic myelopathy, surgery is legitimate . Further randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm the effectiveness of cervical traction and underpin the technique’s indications in CR.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

La névralgie cervicobrachiale (NCB) est une douleur naissant au cou et irradiant vers le membre supérieur de topographie métamérique. C’est une pathologie fréquente avec une incidence annuelle aux alentours de 83 pour 100 000 et une prévalence qui augmente au cours de la cinquième décennie (203 pour 100 000) . L’étiologie la plus fréquente (70 à 75 %) est la compression d’une racine cervicale au niveau du foramen de conjugaison secondaire à la diminution de la hauteur du disque intervertébral et aux phénomènes dégénératifs articulaires uncovertébraux en avant et zygapophysaires en arrière . Contrairement au rachis lombaire, la hernie discale (HD) ne représente que 20 à 25 % des étiologies . Plusieurs stratégies d’intervention sont utilisées dans la prise en charge de la NCB allant des approches conservatrices, incluant le traitement physique, à la chirurgie.

Dans trois quarts des cas, le traitement est conservateur médical et rééducatif . Les programmes de rééducation sont multiples et comportent plusieurs moyens physiques sans certitude de leur efficacité. La traction cervicale, utilisée dans les cervicalgies post-traumatiques , figure parmi les moyens physiques les plus fréquemment utilisés dans la NCB .

Notre objectif à travers ce travail est l’évaluation de l’effet de la traction cervicale intermittente manuelle ou mécanique sur la douleur, la consommation d’antalgiques et le handicap ressenti au cours de la NCB récente.

2.2

Patients et méthodes

2.2.1

Patients

Notre population est formée de patients adressés pour un traitement rééducatif d’une NCB.

Les critères d’inclusion sont une NCB récente de durée d’évolution inférieure à trois mois, un conflit radiculaire avec une HD et/ou une discarthrose confirmée par l’imagerie (une tomodensitométrie et/ou une imagerie par résonance magnétique) avec concordance radioclinique. Les critères d’exclusion sont des antécédents de chirurgie ou de lésions ostéoligamentaires du rachis cervical, les antécédents de pathologies de l’épaule (syndrome de la coiffe des rotateurs, capsulite rétractile, arthropathie acromioclaviculaire, épaule instable et rhumatisme inflammatoire), les antécédents de syndrome du canal carpien, un traitement rééducatif déjà accompli ou débuté pour le problème actuel de NCB et l’aggravation des douleurs ou la non tolérance du test de traction cervicale manuelle réalisé par le clinicien lors de la première consultation. Les patients sont adressés par les rhumatologues, les orthopédistes et les neurologues du CHU de la ville de Monastir (Tunisie) ainsi que par les praticiens libéraux de la région.

2.3

Méthodes

Il s’agit d’un travail prospectif randomisé réalisé durant la période allant d’avril 2005 à octobre 2006. Nous avons répertorié 51 cas de NCB. Douze patients ont été exclus et 39 ont été inclus successivement et répartis au hasard, en s’aidant d’une liste de randomisation, en trois groupes : A, B et C. Dans le groupe A, le traitement comportait une rééducation « classique » comprenant des moyens physiques à visée antalgique (ultrasons, infrarouge s et massages décontracturant s ), des mobilisations douces du rachis cervical, un renforcement musculaire par des contractions isométriques des muscles fléchisseurs et extenseurs suivi d’étirements et par des exercices d’auto-agrandissement pour les spinaux. Des tractions cervicales manuelles intermittentes (20 tractions de 20 secondes chacune avec dix secondes de repos entre les tractions) ont été réalisées par les kinésithérapeutes, chacun pour ses patients correspondent ( Fig. 1 ). La force développée par les kinésithérapeutes est aux alentours de 6 kg. Cette charge a été calculée grâce à un dynamomètre mécanique et correspond à la force que peut développer les kinésithérapeutes pendant 20 secondes à raisons de 20 répétitions successives sans éprouver de fatigue importante. Elle a été mémorisée et rappelée au début de chaque séance de traction manuelle. Dans le groupe B, la rééducation « classique » a été associée aux tractions mécaniques en décubitus dorsal avec un système de poids-poulies ( Fig. 2 ). Au cours de chaque séance, il a été réalisé deux tractions de 25 minutes chacune intercalées par un intervalle de repos de dix minutes. Le poids est augmenté progressivement de cinq à 12 kg. L’axe du cou au cours des tractions est déterminé en fonction de la posture antalgique vérifiée par le test de traction manuelle lors de la première consultation. Les patients du groupe C ont été traités par une rééducation « classique » seule. Chaque protocole comportait 12 séances réalisées à raison de trois par semaine. Les patients ont été répartis entre deux kinésithérapeutes après tirage au sort puisque sur le plan pratique, il nous a été difficile de confier tous les patients à un seul kinésithérapeute. Les contrôles ont été faits à la fin du traitement, à un, trois et six mois par un médecin ne connaissant pas la nature du traitement prescrit ( Fig. 3 ).