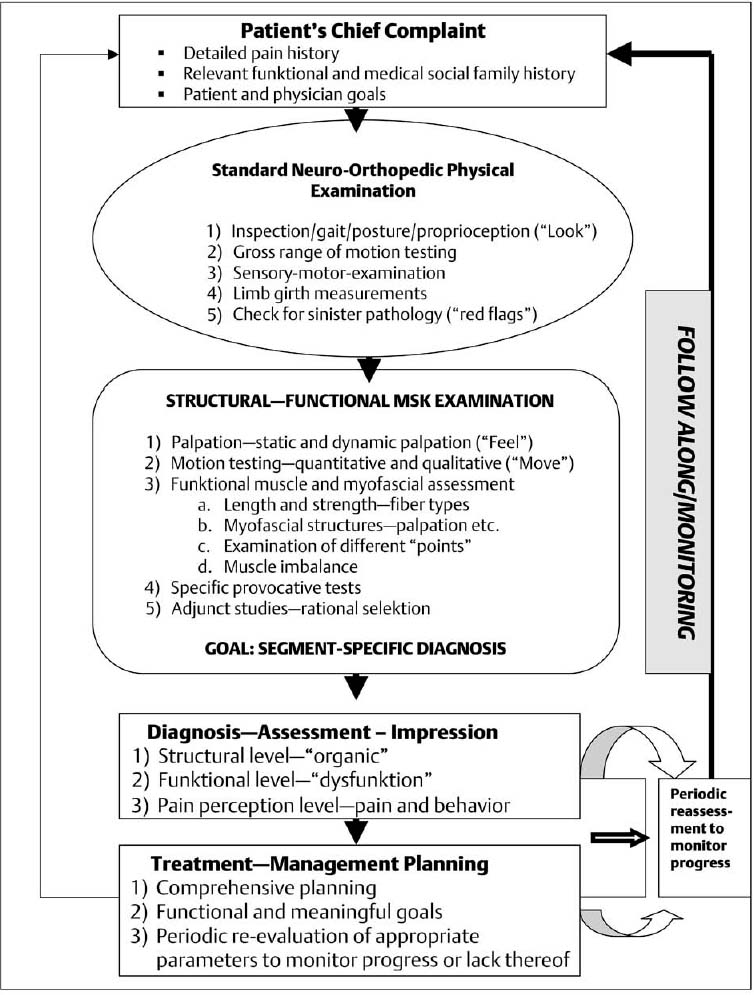

7 The Structural and Functional Neuro-Musculoskeletal Examination The neuro-musculoskeletal (NMSK) examination assesses both the structure and function of the spine and the extremities. The comprehensive examination has evolved into a vital component in the evaluation and treatment of a patient when in pain or suffering from loss of function. The structural and functional NMSK evaluation, however, is not an isolated or stand-alone examination approach to the many painful syndromes. Instead, it can easily be integrated into the other existing examination routines used in such fields as neurology, orthopedics, rheumatology, physiatry, sports medicine and others (Fig. 7.1). In short, this examination has also been referred to as the structural examination of the musculoskeletal system with the following goals: 1. To arrive at a structurally and functionally sound diagnosis. 2. To determine the most appropriate treatment intervention according to the specific objectively verifiable findings and particular functional needs of the individual patient, for both short- and long-term management. As stated earlier, the structural musculoskeletal examination is not a “stand-alone” procedure but rather proceeds within the clinical context of the individual patient. It typically follows the standard neurologic and orthopedic examination. The six principal categories are as follows: 1. Observation (“look”). 2. Palpation (“feel”). 3. Motion testing (“move”). 4. Functional muscle evaluation. 5. Provocative testing. 6. Adjunct diagnostic studies. A similar approach (“look”–“feel”–“move”) was recently presented by the Association of American Medical Colleges (2005). • The various musculoskeletal structural components are palpated in two ways: – Static palpation: the patient is not moving while the tissues are palpatorily evaluated by the operator (various techniques). – Dynamic palpation: motion of a region or specific spinal segment is introduced (which can be active or passive) to assess specific motion restriction in three dimensional space and the various tissue-reactions associated with that motion. The dynamic palpatory examination is also known as motion palpation and is addressed specifically below. • Active and passive motion testing is used to determine regional and segmental dysfunctions. • In addition to the standard quantitative assessment of range of motion, the quality of movement, specific motion restrictions, and the particular end-feel are evaluated. • Assessment of muscle length and strength. • Assessment of the various myofascial structures as to their pliability, stiffness, resistance to active and passive motion, abnormal “firing patterns,” and other deviations from normal. • Assessment of “tender points” in fibromyalgia. • Assessment for myofascial trigger points. • Assessment for spontaneous non-fibromyalgia “tender points” (according to the “strain-counterstrain” system described originally by Jones [1981 and 1995]). • Provocation testing may aid in the determination of which technique or direction of treatment may be indicated or is most suitable. • The timing and choice of the particular individual study are based on the specific objective and functionally meaningful findings obtained in the patient-centered history and the detailed examination routine, including findings from the structural and functional examination routine. These components will be reviewed in some detail below. Fig. 7.1 The structural–functional musculoskeletal examination sequence for the integrated manual medicine approach. Observation occurs at two general levels, in form of a: (1) generalized or gross observation; and (2) the regional and localized (e. g. segmental, facet-level) observation. The generalized observation, which may already have been done during the initial neurologic or orthopedic examination, checks for gross postural abnormalities such as scoliosis, uneven shoulder or pelvis levels, head-forward carriage and obvious signs of trauma, prior surgery or applications of orthoses or prosthetics. The regional or segmental observation takes into account observable regional or segmentally related skin changes, swelling, signs of trauma, or other visible changes that deviate from the “normal.” The palpatory assessment of the various joint and osseous structures, including the overlying skin and associated fasciae, muscles, tendons, and ligaments, plays a central role in the integrated structural and functional NMSK assessment routine. Numerous palpatory approaches have been described in the field of manual medicine. The aim is to obtain additional information not immediately recognizable by the naked eye or by particular laboratory or other diagnostic studies. According to De Gowin and De Gowin (1981), the usual definition of palpation is the act of feeling by the sense of touch. The same authors elaborate on the art of palpation by stating that: “As in inspection, all normal persons possess these senses—tactile, temperature and kinesthetic positional and vibrational senses—but practice and special intellectual background in medicine enable the physician to extract meaning that escape the layperson. If the reader doubts the influence of practice on palpation, let him observe a blind person reading a book printed in Braille, then close his eyes and attempt to distinguish between two Braille letters by touching them.” Isaacs and Bookhout (2002) emphasize the need to develop adequate palpatory skills through repeated practice: “One of the difficulties people have in understanding and applying techniques of manual medicine is that both diagnosis and treatment require a degree of palpatory skill that is different from, and in some ways greater than, that used in other branches of medicine.” According to Greenman (1996), palpatory skill affects the following five key components of palpation in the assessment of the musculoskeletal system: 1. The ability to detect tissue texture abnormality. 2. The ability to detect asymmetry of position, both visual and tactile. 3. The ability to detect differences of movement in total range, quality of movement during the range, and quality of sensation at the end of range of movement. 4. The ability to sense position in space of both the patient and examiner. 5. The ability to detect change in palpatory findings, both improvement and worsening over time. To be able to accurately assess and interpret the relevant palpatory finding, Greenman (1996) finds it essential that the physician fully concentrate on the act of palpation, the tissues that are being palpated, and the response of the palpating fingers and hands. Probably the most common mistake in palpation is the lack of concentration by the examiner. Usually, palpation is started in the general area that is indicated by the patient as the most painful. However, if the area is exquisitely tender, the examiner may start in an adjacent area or the corresponding area on the other side of the body so as to obtain an initial impression of the tissues. Comparison of symmetrical skeletal parts may be helpful but can also be misleading at times: disturbances may actually occur symmetrically, limiting the value of such a comparison. Thus, it is recommended to compare similar tissues or structures on the same side as that of the functional abnormality, or, if appropriate, to compare with locations with a similar anatomic arrangement on the unaffected side. When changes are present in neighboring or analogous structures, the palpatory assessment is an important part of the examination in differentiating the offending source (s) from those structures that are secondarily affected. When searching for painful or abnormal tissue changes, the palpating finger or fingers should remain at the same tissue level; that is, there should be no “deep probing” but, rather, the palpation should proceed carefully from layer to layer. This is referred to as flat palpation. Pain may be present at rest or may only become apparent with movement, induced either by the patient or the examiner. The patient is often able to localize the pain to one specific point or some general area when a particular, isolated structure is involved. The patient may also spontaneously point to a contracted muscle band, which may be tender either at rest or upon introduction of movement. However, the pain may be diffuse and not well localized in other situations, in particular with chronic pain, where, over time, a number of adaptive and compensatory changes may have altered the initial pain presentation. While general palpation can be applied to every part of the body accessible to the examining fingers or hand, including solid abdominal viscera and solid contents of hollow viscera (De Gowin and De Gowin, 1981), the musculoskeletal palpatory assessment discerns information about the skin and hair, bones, joints, fascial and tendon sheaths, ligaments, superficial arteries and veins, as well as superficial nerves, accumulation of body fluids, joint swelling, tenderness, and heat, and also assists in localizing particularly painful or tender structures. The following are assessed through the practice of layer palpation (Greenman, 1996): 1. Skin (thickness, moisture, temperature, smoothness). 2. Subcutaneous tissues (thickness, ease of displacement and compressibility). (a) Note, this layer may reflect best or directly the tissue texture abnormalities associated with somatic dysfunction (abnormal segmental motion with tissue changes). (b) Within the subcutaneous fascial layer are found the vessels, arteries, and veins. 3. Deep fascia (smoothness, firmness, continuity of fascial sheaths). (a) In particular the muscle septa separating the various muscle bundles of one group from another can be palpated. (b) Palpatory assessment can distinguish between the various muscle groups; moving “between” the various muscles, one can then advance to the deeper structures. 4. Evaluation of muscle, muscle tone, and muscle fiber direction. (a) Determination whether there is “normal” muscle tone versus increased muscle tone from muscle “spasms” (physiologically “normal”) tospasticity; assessment of hypotonic muscles (denervation, atrophy, etc.). (b) The muscle itself is palpated either along its longitudinal axis, in particular toward its insertions, or perpendicular to its length, especially at the level of the muscle belly (Fig. 7.2). A muscle spasm reveals increased “tension” and diminished plasticity, and is usually tender upon palpation. (c) Individual muscles may be identified and distinguished from each other by palpating along their septal divisions. 5. Myotendinous junction. (a) An area that is particularly vulnerable to injury and tears in response to abnormal loading/mechanical stress situations. (b) When injured, this area may appear as “rough” in comparison with the surrounding muscle tissue and can also be exquisitely tender. 6. Tendon and tendon sheaths. 7. Ligaments (example: transverse carpal ligament). 8. Joint capsule. (a) Palpable joint capsules are present in pathological joints and are not usually found in somatic dysfunctions. (b) According to Greenman (1996) direct-action thrust treatment (high-velocity, low-amplitude thrust, for instance) should not be performed when the joint capsule is actually palpable. 9. Bone. (a) Bone is not palpated directly. Its surface and structures are “inferred” by palpating through the overlying soft tissues. Some areas are naturally more easily accessible to palpatory assessment than others.

Introduction

Observation

Palpation

Motion Testing

Functional Muscle and Myofascial Assessment

Specific Provocative Tests

Rational Selection of the Relevant Adjunct Diagnostic and/or Laboratory Studies

Observation (“LOOK”)

Palpation (“FEEL”)

Definitions; Required Skills; Applications

NMSK Structures Examined by Palpation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree