CHAPTER 4 The Stiff Knee

ANATOMY AND PATHOANATOMY

Anatomy

Normal Knee Range of Motion

The knee has been described as having 6 degrees of freedom—internal-external rotation, compression-distraction, medial-lateral translation, abduction-adduction, anterior-posterior translation, and flexion-extension. Normal extension is 0 degrees, but some individuals may have slight hyperextension of up to 5 degrees. Normal knee flexion is 140 degrees in men and 143 degrees in women. Knee flexion up to 165 degrees is seen in certain groups.1 The functional range of motion for most activities of daily living is 10 to 120 degrees. Loss of knee flexion or extension can lead to significant disability and inability to perform simple every day activities. Studies looking at gait patterns have shown that 67 degrees of knee flexion is required in the swing phase of walking, 83 degrees to ascend stairs, 90 degrees to descend stairs, 93 degrees to rise from a standard chair, and 110 degrees to cycle upright.2

Potential Locations of Entrapment

Suprapatellar Pouch.

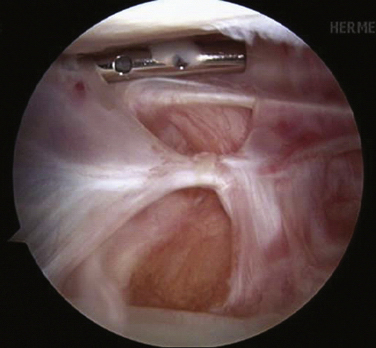

The suprapatellar pouch, also referred to as the suprapatellar bursa, is the superior continuation of the knee joint. This area is posterior to the quadriceps tendon and anterior to the femur. It continues on either side of the patella as the medial and lateral gutters. This area is covered by a synovial membrane. The suprapatellar pouch should extend 3 to 4 cm above the patella. It is the most common area of arthrofibrosis. With extensive scarring of the suprapatellar pouch, knee flexion is typically lost (Fig. 4-1). Terminal extension is usually not affected as much.

Medial and Lateral Compartments.

The medial and lateral compartments contain deep capsular ligaments and menisci. Loose bodies or bucket handle meniscal tears in these compartments may lead to restricted range of motion. It is important to evaluate these at the time of surgery and address any pathology found.

Anterior Interval.

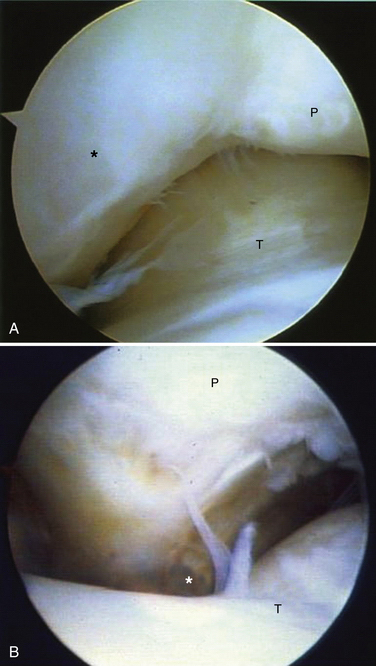

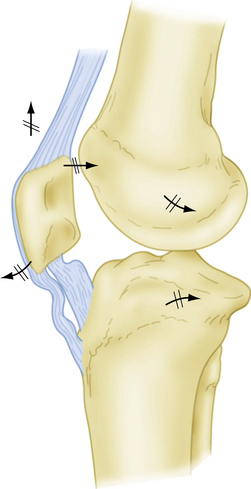

This potential site of entrapment includes the fat pad, patellar tendon, and retropatellar recess. The anterior interval is bordered anteriorly by the fat pad and patellar tendon, posteriorly by the intracondylar notch and anterior border of the tibial plateau, superiorly by the patella, and inferiorly by the tibial tubercle. The retropatellar recess is a space between the insertion of the patellar tendon and anterior border of the tibia. Extracapsular structures in this area include the medial and lateral patellotibial ligaments. These structures can become contracted, leading to progressive arthrofibrosis of the knee. When fibrosis and scarring occur in the anterior interval, the patella may be drawn inferiorly, creating patella baja. However, patella baja, or patella infera, may not always occur with arthrofibrosis unless a dense band of scar forms between the inferior pole of the patella and anterior aspect of the tibial plateau (Fig. 4-2). This pseudopatellar tendon can severely hinder knee motion and lead to patella tendon resorption. Loss of flexion and extension may be present in those patients with anterior interval involvement (Fig. 4-3).

Pathoanatomy

To treat arthrofibrosis successfully, the surgeon must identify the cause. Failure to indentify the cause and correct it will most likely lead to recurrence of the stiffness.

Potential Causes of Knee Stiffness

Immobility.

The effects of immobility, regardless of the cause, are always the same. Prolonged immobilization of the knee causes progressive contracture of the capsule and pericapsular structures. It also causes encroachment on the joint by fibrofatty connective tissue. The border between the cartilage and fibrous tissue may become indistinguishable. This can eventually lead to joint cavity obliteration. Pressure necrosis, erosion, and cysts occur where cartilage surfaces contact one another for prolonged periods. The subchondral plate is invaded by mesenchymal cells, destroying the deep cartilage layers.3

Ligament Reconstruction Technical Errors.

Every knee that has had surgery or injury demonstrates decreased knee motion and patella tightness as it progresses through the normal healing process. However, certain factors can increase the chances of arthrofibrosis. Malposition of tunnels for ligament reconstruction can lead to a stiff postoperative knee. With anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction, if the tibial tunnel is too anterior, the graft will impinge on the roof of the notch, thus limiting extension.4 If the femoral tunnel is too anterior, the graft will become taught too early in flexion, limiting terminal flexion.5 Overtensioning of the graft during ligament reconstruction can overconstrain the knee as well.

Timing of Surgery.

Acute ligament reconstruction of the knee has been shown to have a higher incidence of arthrofibrosis than delayed reconstruction. Shelbourne and colleagues found a statistical difference in postoperative range of motion in patients who had ACL reconstruction performed within 1 week of the injury compared with those who had reconstruction 3 weeks after the injury.6 Harner and associates found the rate of arthrofibrosis to be 37% in the acutely reconstructed knee as compared with 5% of those who had delayed reconstruction.7 Others have found no difference in arthrofibrosis rates and surgical timing. Bach and coworkers found no difference in the range of motion between acute and chronic reconstruction.8 It is our opinion that the condition of the soft tissue dictates the timing of the surgery. If the patient has good active quadriceps control, near-normal preoperative range of motion, and no longer has a warm swollen knee, then surgical reconstruction may be undertaken safely, regardless of the time from injury.

Patient Factors.

Some patients are more prone to scar formation. Patients with genetic disorders such as scleroderma are predisposed to arthrofibrosis. Other patients may not have a specific genetic disorder but have a higher likelihood of forming fibrotic tissue. These fibrotic healers are at an increased risk for arthrofibrosis, regardless of other potential causes. They tend to produce keloid scars. Careful attention at the time of the history and physical examination may lead the surgeon to recognize patients who may be at a higher risk for the development of a stiff knee. Some research has focused on finding specific genetic alleles responsible for arthrofibrosis. Skutek and colleagues looked at 17 patients who developed arthrofibrosis after ACL reconstruction. They found that patients with arthrofibrosis were less likely to have allelic group HLACw*07 and more likely to have allelic group HLACw*08 on human leukocyte antigen (HLA) loci.9

Fat Pad Trauma.

Albert Hoffa, a German surgeon, first described a condition characterized by traumatic and inflammatory changes occurring in the infrapatellar fat pad in young athletes. These changes may lead to pain, swelling, and restricted motion of the knee. Hypertrophy of the fad pad may cause it to become entrapped between the tibia and femur. Catching of this hypertrophied fat pad may occur when the flexed knee is extended suddenly. If this condition persists for a significant period, fibrosis may develop.