Chapter 10 The spine

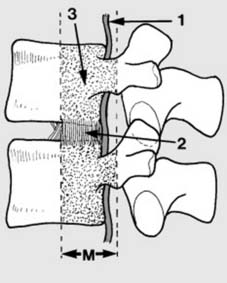

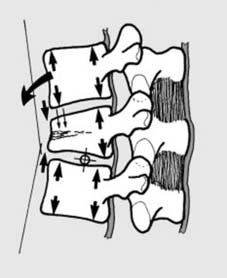

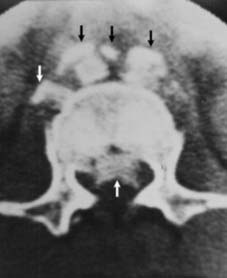

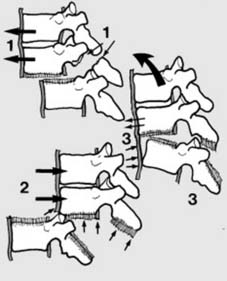

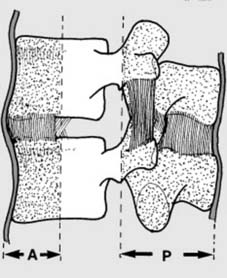

7 Assessment of spinal injuries (c): The posterior column (P), vital for stability, comprises the neural arch, the pedicles, the spinous process, and the post. ligt. complex. The anterior column (A) is formed by the anterior longitudinal ligament, and the anterior parts of the annular ligament and vertebral body. Note that failure of these columns in their role as supports can be due to bony or ligament involvement. Four categories are recognised in the Denis Classification of spinal injury:

13. Neurological examination: basic principles: Where there is evidence of a deficit, a thorough neurological examination is required on admission; this must include as a minimum:

Note also the following points:

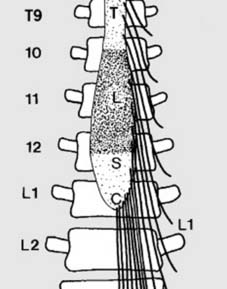

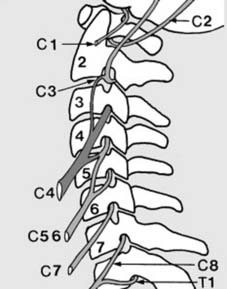

15 Anatomical features (b): Cervical cord:

2. C2 and C3 supply the vertex and occiput (accounting for pain here in upper cervical lesions).

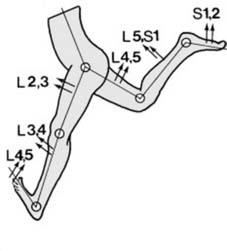

C5–T1 contribute to the brachial plexus. (The illustration is diagrammatic.)

18. MRC grading: Muscle activity should be assessed using the MRC scale:

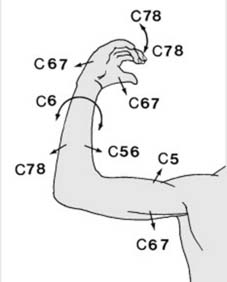

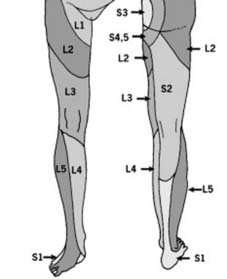

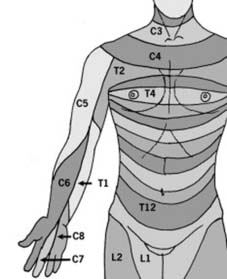

19 Dermatomes (a): In the upper limb, the anterior axial line follows the line of the second rib from the angle of Louis, and continues down the anterior aspect of the arm, splitting near the middle finger which is supplied by C7. The other dermatomes are arranged in a regular fashion on either side of the axial line. If indicated, a sensory index score may be made for each limb (0 = absent sensation; 1 = impaired; 2 = normal).

21 DETERMINING THE SEVERITY OF NEUROLOGICAL INVOLVEMENT

TYPES OF INCOMPLETE CORD INJURY:

A number of cord syndromes are recognised. These include the following.

Central cord syndrome

This is the commonest incomplete cord syndrome, and generally follows a hyperextension injury. It is particularly common in the older patient who has a degree of cervical spondylosis (see also Frame 71). The cord may be affected over several segments, with involvement of both grey and white matter. The effects are curiously greater in the arms than in the legs. In the upper limbs, lower motor neurone lesions predominate, with a partial flaccid paralysis of the fingers and arms, and loss of pain and temperature sensation. In the lower limbs the lesion is an upper motor one, resulting in a spastic paralysis, usually with sparing of sensation, but sometimes with bladder and bowel involvement. This lesion pattern is sometimes referred to as ‘man in a barrel’ syndrome (MIB), a typical example being an elderly man who is able to walk but whose shoulders are immobile and his hands anaesthetic.

THE COMMON LESIONS

22 Injuries to the cervical spine: Diagnosis: Suspect involvement of the cervical spine where the patient: 1. Complains of neck, occipital or shoulder pain after trauma; 2. Has a torticollis (Illus.), complains of restriction of neck movements or supports the head with the hands, or 3. Is found unconscious after a head injury, especially in road traffic accidents. In all cases, further investigation by radiographs is essential.

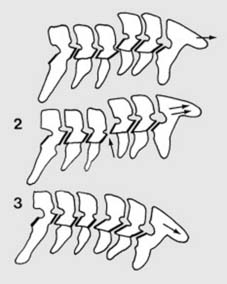

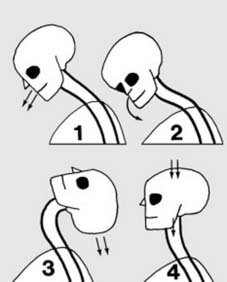

28 Classification of cervical spine injuries: Injuries of the cervical spine may be grouped according to the mechanism of injury:

34 Unilateral dislocation (c): The oblique radiograph shows a dislocated facet joint. In all cases requiring reduction a pre-operative MRI scan should be carried out to exclude a disc rupture: a significant prolapse may merit an anterior discectomy and interbody fusion in case manipulation precipitates a further disc protrusion and a catastrophic neurological problem. In the elderly especially, manipulative reduction also carries a risk of causing a central cord syndrome, so that an open procedure may then be preferred.

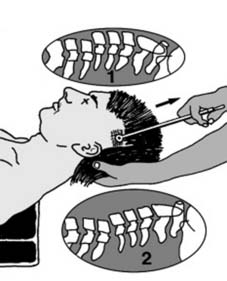

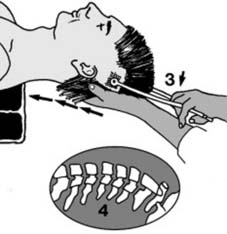

35 Unilateral dislocation (d): On clinical examination of the patient with a unilateral dislocation, the head is slightly rotated and inclined to the side (1) away from the locked facet (2). There is often great pain with radiation (3) due to pressure on the nerve root at the level of the affected joint, and (rarely) there may be cord involvement. Proceed to treatment if there is no neurological defect or significant disc prolapse: otherwise see Frame 25.

40 Flexion/rotation injuries: Unstable injuries (a): The commonest injury is a cervical dislocation without fracture. Displacement may be severe, and there is frequently locking of both facets. Damage to the posterior ligament complex is always present. (This may be associated with an avulsion fracture of a spinous process, widening of the gap between two spinous processes or evidence of forward slip on a flexion lateral.) An MRI scan is advised to exclude a significant disc prolapse. (See Frame 70.)

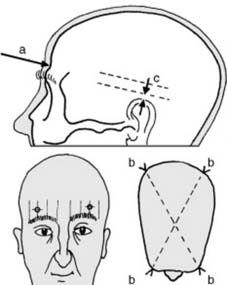

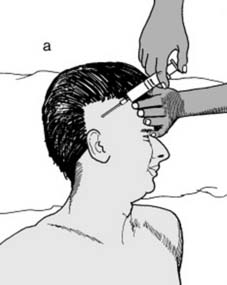

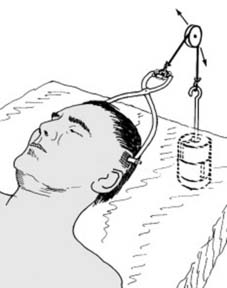

46 Applying skull tongs (b): Make a small incision (about 1 cm in length) on each side down to bone (b). Bleeding is usually brisk, but generally controllable by firm local pressure applied for a few moments; if not, secure and tie off any remaining bleeding points. Now insinuate one point holder through the temporalis muscle fibres until it is in contact with the skull (c).

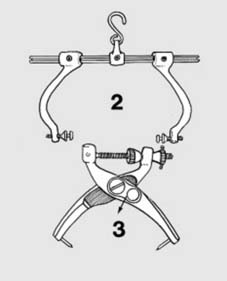

52 Reduction (c): Alternative techniques: Continuous (weight) traction may be used to overcome muscle tension and unlock overriding facets. Control the direction of traction with the position of the traction pulley, or by pads under the head or shoulders. The amount of traction can be adjusted by the weights: allow 10 lb (4.5 kg) for the head + 5 lb (2.3 kg) for each interspace above: e.g. 35 lb (16 kg) for C5 on C6. The duration of maximal traction is monitored by radiographic progress.

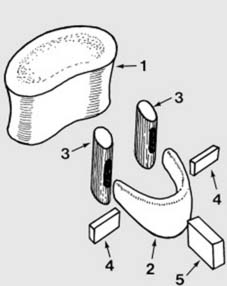

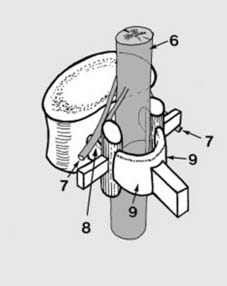

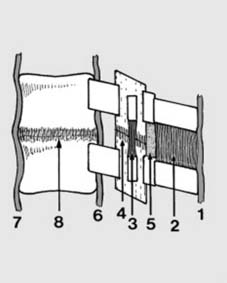

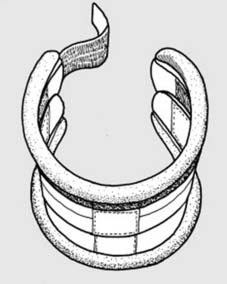

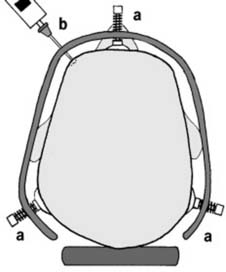

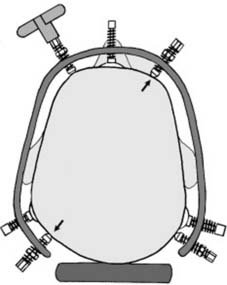

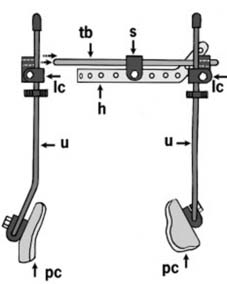

56 The halo vest (a): The halo (h) may be attached to a vest (or cast), with additional components. On each side, a transverse bar (tb) is screwed (s) to the halo. These in turn are fixed to 4 uprights (u) with locking couplings (lc). The caudal ends of the uprights are attached through additional couplings fixed to plastic connectors (pc). These may form integral parts of a vest, or be incorporated in a plaster cuirass or jacket.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

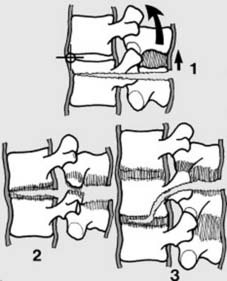

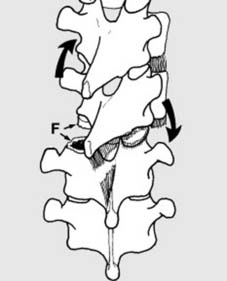

Full access? Get Clinical Tree