Chapter 4. The significance of the carer

The scenario recorded in Box 4.1 was actually an informal note, scribbled ‘stream of consciousness’ style in the period after lunch one day. I had not long arrived on the unit, and it was written perhaps in part as abreaction. I thought that all my years in dementia care had inured me to disturbing sights and sounds; but this rattled me badly, and I felt a need to get it down on paper so that I could take it away and look at it more objectively some time when I could feel less emotional about it.

Box 4.1

Hester is dominating the room with her noise – something like ‘ooh wa ow/beh ow ow/wm ma el we’. It is very loud and accompanied by much circling of the right hand and pointing of the index finger. She looks as though she is laying down the law. Jim comes over, leans over her chair and tries to smack the waving hand. She smacks back and Jim goes away. Elsa on Hester’s right is lost in her own repetitive ‘My daddy oooh’, the my daddy being spoken and the oooh being a long sung note. She is rubbing the fingers of one hand over the fingers of the other. She is in her bubble, but one might imagine that she is making her own noise in competition with Hester – if she mutters and ooohs, she might be able to block out Hester’s noise. Marion, two chairs away from Hester, now starts her own special noise, a guttural sound from deep within her throat, as though someone has just stabbed her and she is about to expire. Her gaze ranges around the room, occasionally passing over me sitting near her on the floor, but not engaging. Opposite, David is lying across a recliner chair. His legs are hanging over one arm with feet resting on the floor. His head, over the other arm, has been supported on two pillows on a dining chair. He is alternately twitching and roaring, and from time to time appears to be rather inefficiently trying to masturbate. The TV is on – nobody is looking at it. Lily is slumped in a chair between Marion and Hester. She is not talking or noise-making. She wipes her nose on her cardigan front. Arthur wanders in and wanders out again. Marion’s noise gets louder and more dramatic. She sounds as though she is being slowly strangled. It is a cacophony of noise. I am reminded of a zoo, but it is not like a zoo. The noises are not animal noises. Nobody is hearing anybody else. Each is trapped in their own world – their own bubble. Margaret must surely have a terribly sore throat by now. Elsa has stopped. She just sits and stares and occasionally rubs her fingers. Jim wanders in again – no shoes, a large hole in the heel of one sock, both name labels on the outside for all to be able to discover who he is. This is supposed to be the quiet room.

This was undeniably a bad day on the unit, and not typical of the usual order of things. Staff had been invisible for some considerable time, perhaps because this time of day in residential care, after lunch, is usually the quiet and uneventful hour when most people are having a snooze. But not today. It was a salutary experience to see what arises without the modifying presence of carers. Even more disturbing than the noise, though, was the complete and utter self-containment of each person in that room. It was as though, for each person, nobody else existed. Even Jim’s contact with Hester was more in the manner of swatting a fly than a true personal interaction. It is possible that there was some communication through noise, one noise sparking off another in a reflex manner, rather as one baby crying might trigger another; but this is conjecture. Certainly there was almost no visual communication; two or three were looking around, but what they were actually perceiving or visually engaging with is a matter of question. It was only when staff returned to the unit, and started to attend to this resident and to that, that the noise very gradually started to abate, and the chaos began to come under control. Eventually, a sense of some order was restored. This was the first time I had found myself using the word ‘bubble’ to describe my perception of the experience of the person with dementia, for that is how it seemed to me: each person trapped in a glasshouse, seeing only through shadow and distortion, hearing only as through a shell.

This event took place within the context of a research project which explored the place of occupation in the lives of people who have a very advanced dementia (Perrin 1997). The project entailed many hours of observations of severely impaired people, and was carried out in a variety of different residential settings. Some of the research findings were what might have been expected by anyone familiar with the general poverty of occupation that often exists in such settings; for example, many people in residential settings spend the greater portion of their waking day unoccupied; most people respond very positively to occupation. But there were some surprises, some very thought-provoking outcomes. We want to cite two of these outcomes in the context of this discussion on the significance of the carer to the person with dementia.

‘Bubble’ was the image that came to mind again as I processed the empirical data of the formal research project. In the preliminary phase, I had used dementia care mapping (Kitwood & Bredin 1992) to measure occupation and wellbeing across nine different dementia care settings, and one exercise in the data processing was to compare the overall wellbeing scores of the different units. Results were not as expected. The unit which was dark, cramped, crowded, incessantly noisy and deeply permeated by what Kitwood (1997) would call a ‘malignant social psychology’ actually had a higher group wellbeing score than the unit which was quiet, spacious, tastefully decorated, and where the overall pattern of care was consistently sensitive and respectful. Similarly, the cavernous, bland Victorian hospital ward at full capacity, had the same group wellbeing score as the newly built, beautifully designed home where the few residents were accommodated in small family-style sitting rooms. This seemed at first very puzzling – I had no doubt about which environments made me feel better (or worse) as I sat in them recording my observations over many months. Why would a person with dementia not feel the same? Well, I have wondered if these data are an indication that the immediate environment may have considerably less impact upon severely impaired people than is commonly imagined. Where most of us attach considerable importance to decor, furnishings and congenial company, and where inspection and registration units set standards on room size, equipment for disability and staffing levels, it is actually unclear how much influence many of these things really have on the well-/ill-being of persons who are well advanced in their dementia.

For the unimpaired person, in the doctor’s waiting room for example, there is likely to be an acute awareness of her environment, whether or not it impinges upon her conscious thought. She will have an appreciation of whether it is crowded or full, light or gloomy, of the decor and furniture, of health promotion posters on the walls. She will be conscious of the comings and goings of patients, and will probably eavesdrop on conversations around the room. If she is kept waiting long enough, she may discover the number of stripes on the wallpaper or the damp patch on the ceiling, or she may choose to extend her environment by looking out of the window. We suspect that this is not the case with the severely impaired person. For such a person, it seems rather as though the environment has ‘shrunk’ to envelop her in a kind of glass bubble, which in most cases is about 3 to 4 feet in diameter; that from inside this bubble, the physical conditions of the general environment, along with the conversations and interactions of everyday social intercourse, are perceived in a distorted and muffled fashion and therefore fail to impinge appropriately upon the individual within. What seems to be critical for the client, is what goes on within the bubble, within those inches of personal space, and this demands a different concept of ‘environment’ on our part, if we are to discover and utilise those approaches which can substantially engage the person inside.

The main body of the research alluded to above measured the wellbeing of severely impaired persons in the context of a range of sensorimotor occupations. There were again some very interesting results. Not only did the greater number of observations testify to the overriding importance of the carer’s presence in the context of the occupation (in fact only two subjects were able to engage in any measure without a carer), but a small number of subjects were so intensively engaged in the personal interaction with the carer delivering the occupation, that they were quite unable to engage with the occupation itself. Why should this be? Is it possible that the greater the impairment, the closer the bubble shrinks to enclose the person inside?

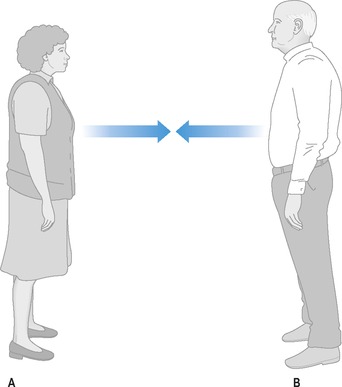

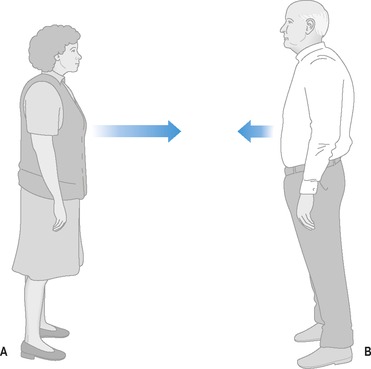

Drama therapist Paula Crimmens (conference address, 1996) has suggested that most human interactions between healthy persons might be represented schematically as shown in Figure 4.1. For a fruitful interpersonal transaction to take place, each party will move towards the other in a measure of some equivalence. New acquaintances will exchange views on the weather and the state of the nation, perhaps share a bus seat or a cup of tea, and relationship is developed. Old friends will share hopes and plans and precious time, and relationship is strengthened and extended. The person with dementia, however (and this may be equally true of persons with other psychological difficulties), has increasing problems as the condition progresses, in making that move outwards toward the other in equal measure. What then occurs, as shown in Figure 4.2 is a fracturing of relationship. Person A has made the usual move of social contact towards person B, but person B’s dementia has now got a little more hold than it had when they last met, and B is no longer able to reciprocate. While both parties hold such a position, the fracture is sustained, the gap is not bridged, and there is no meeting point.

|

| Figure 4.1 |

|

| Figure 4.2 |

In the case described in Box 4.2, there was as yet, certainly no shortage of communication between Harry and Joan – in fact, they were arguing far more than they ever used to. There always seemed to be something to squabble about; nobody could accuse them of not communicating. But there was no meeting, and there is a subtle difference. Harry had changed. He no longer thought very much about how he looked, he just wanted to be comfortable. Nor was he able to concern himself with Joan’s embarrassment and shame, he could only feel her anger. Harry was no longer able to move out towards Joan as he once would. Joan, for reasons of her own interior pain and resistance, was unable to move any further towards Harry. An impasse had been reached; there was no meeting, just a yawning chasm which was threatening to grow ever wider.

Box 4.2

Harry had had dementia for about 3 years. He had been a smart man all his life; he had a military bearing, and was always immaculately dressed. But over the last year, his wife Joan felt that he had begun to neglect himself. There were three things that she found difficult. The first was that Harry no longer seemed to be bothered about wearing a tie; but he had always worn a tie, even in casual dress, and Joan felt that he should continue to do so. It was important to keep things as normal as possible, and she felt uncomfortable that he should be seen without. The second thing that rankled was that he had started to slouch and shuffle; gone was the upright demeanour and firm step. Although it was hard to admit, he looked untidy and sloppy, as though he’d given up and couldn’t be bothered any more. And perhaps the most difficult thing was that he, a man of impeccable manners, was starting to mess with his food. He ate slowly and fiddled with the contents of his plate. Food would often end up on the table or on the floor or down his front. It sometimes made her feel sick.

Joan brought some of her distress and discomfort to the carer’s group, describing the effort she was going to, to hang on to the old Harry. She would insist upon his wearing a tie, and would usually put it on and tie it for him; she had constantly to be chivvying him to stand up straight and walk properly like he used to, and it seemed that she had to have a cloth permanently in her hand at mealtimes, for she couldn’t bear all the spills and splodges. The most distressing thing though, was all the rows they were now having. Harry shouted at her and called her an interfering old cow; he had even once or twice lifted his hand towards her, something he had never ever done in all their years of marriage. She just couldn’t understand why dementia should make a person so angry.

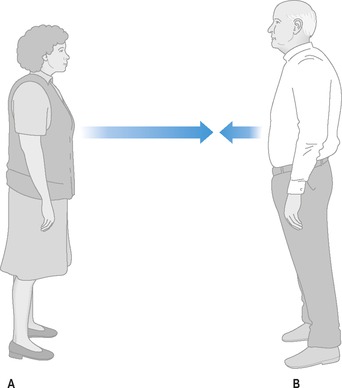

Friends in the carer’s group were very concerned about this situation. Joan had begun to fear for her own safety, and her friends thought privately that she was quite justified in doing so. But they also saw what Joan herself seemed unable to see, that it was her failure to accept and adapt to the change in Harry that was actually at the root of the arguments and conflict. Because of his cognitive impairments, Harry couldn’t change or move. Resolution in any measure, would have to come through Joan, and it would mean having to adopt a position such as that shown in Figure 4.3. Each retreat by Harry would require a further advance by Joan if true meeting was to be sustained over the course of his dementia. The effort and sacrifice and self-denial would have to be all hers. As it turned out, Harry died before his dementia got very much worse, and it was generally felt that perhaps this was the best thing, for Joan seemed unable to move very far at all. It had nothing to do with love or compassion or commitment, for Joan had these in abundance. But somewhere within, there was some fear and damage and despair of her own, which held her back from being able to accommodate herself to her husband’s greater needs.

|

| Figure 4.3 |

The case in Box 4.3 amplifies further the issue of ‘different worlds’. What Joan had been unable to do for Harry, and the careworker for Audrey, Julie was able to do. Between Joan and Harry, and careworker and Audrey, there was a communication gap – each was interacting with the other, but there was no meeting. Joan was unable to understand the change in Harry, or his inability to be to her what he once was, and she couldn’t bridge the gap; they remained estranged and at loggerheads. The careworker either couldn’t, or didn’t want to understand that there was still a person inside Audrey, able to feel and understand and respond; they remained alienated. Julie however, who in terms of age and culture was a million miles distant from Audrey, did understand. She was able to accept Audrey as she was, unconditionally. She knew that Audrey had no ability to come to her, so she went to Audrey. She crossed the gap – by appreciating Audrey’s needs, and adapting her own expectations and actions accordingly. She had established a point of meeting, and harmony of relationship was the result.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree