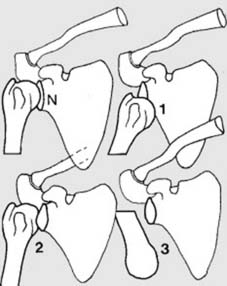

Chapter 6 The shoulder girdle and humerus

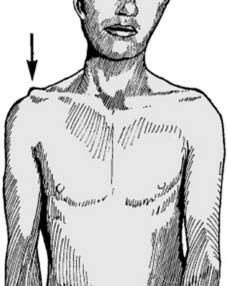

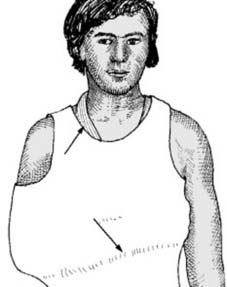

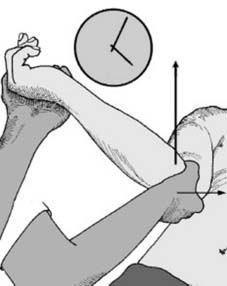

1 Clavicular injuries: mechanism of injury: Most (94%) clavicular injuries result from a direct blow on the point of the shoulder, generally from a fall on the side (A). Less commonly, force may be transmitted up the arm from a fall on the outstretched hand (B). Under the age of 30 years, road traffic and sporting injuries are the commonest causes.

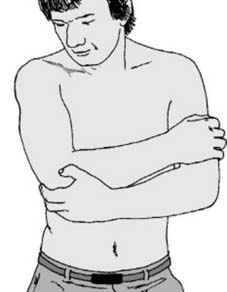

6 Diagnosis: Clinically there is tenderness at the fracture site; sometimes there is obvious deformity with local swelling, and the patient may support the injured limb with the other hand. In cases seen some days after injury, local bruising is often a striking feature. Diagnosis is confirmed by appropriate radiographs; a single AP projection of the shoulder is usually adequate in the adult.

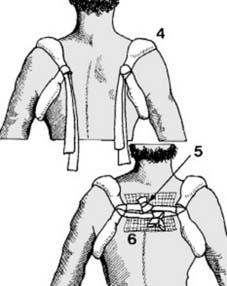

12 Treatment (f): Commercially available clavicle rings, covered with chamois leather, may be applied and secured with a strap. Many other patterns of off-the-shelf clavicular supports are available. With all of these care must be taken to avoid pressure on the axillary structures and the additional support of a sling is desirable for the first 2 weeks or so. Note also that elderly patients tolerate clavicular bracing methods poorly, and sling support only may be advisable. (For internal fixation see Frame 25.)

18 Diagnosis (c): Now stand behind the patient and abduct the arm to 90°. Flex and extend the shoulder while gently palpating the acromioclavicular joint. Failure of the outer end of the clavicle to accompany the acromion indicates rupture of the conoid and trapezoid ligaments.

23 Treatment (d): If a dislocation reduces with the arm in abduction, a shoulder spica for 6–8 weeks may be used as an alternative to surgery. Complications: Symptoms from acromioclavicular osteoarthritis may be relieved by excision of the outer 2 cm of the clavicle. Fascial reconstruction of the coracoclavicular ligaments can be used for persistent instability.

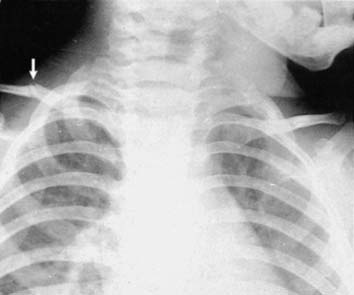

27 Radiographs: AP and oblique radiographs are difficult to interpret but are nevertheless usually performed; they may confirm the diagnosis when there is a major dislocation and the inner end of the clavicle is displaced onto the sternum. Note that in rare cases (illustrated) the clavicle passes behind the sternum where it may endanger the great vessels. As a rule tomographs or CT scans may be more useful in elucidating these injuries. (Clavicle: dotted line; sternal edge: arrows.)

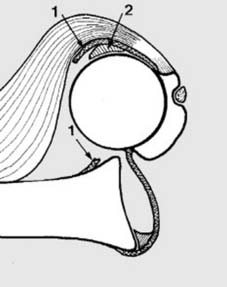

29 Treatment (b): Gross displacements should be reduced under general anaesthesia. A sandbag (1) is placed between the shoulders which are firmly pressed backwards (2). Clavicular braces are then applied (see Ch. 6/Frame 9), along with a broad arm sling for 4–5 weeks. Should the reduction be extremely unstable, surgical repair with fascia lata slings should be considered. The rare irreducible dislocation may require open reduction (which may be hazardous).

33 Anterior dislocation (a): This most commonly results from a fall leading to external rotation of the shoulder (e.g. the trunk internally rotating over a fixed hand – the shoulder being vulnerable in abduction and external rotation). It is rare in children, common in the 18–25 years age group (from motorcycle and athletic injuries) and comparatively common in the elderly, where the stability of the shoulder may be impaired by muscle degeneration and where falls are common.

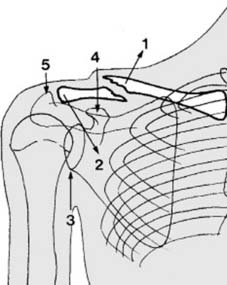

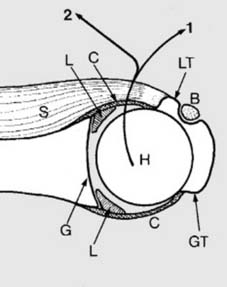

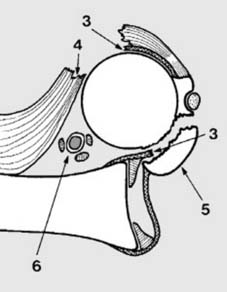

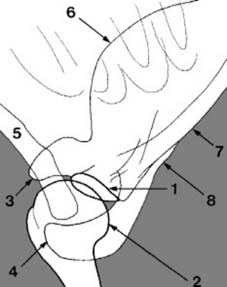

35 Anterior dislocation (c): Anterior dislocation is inevitably associated with damage to the anterior structures. Commonly the capsule is torn away from its attachment to the glenoid (1). (The Bankart lesion, although simultaneous displacement of the glenoid labrum (2) usually attracts this term.) The humeral head may suffer an impression fracture (Hill-Sachs lesion (see Ch. 6/Frame 71). Other damage may occur, especially humeral avulsion of the glenohumeral ligament (HAGL lesion).

39 Diagnosis (c): Nevertheless the presence of the acromion and clavicle may make examination difficult. In the doubtful case, it may be helpful to try to assess the relative positions of the humeral head and glenoid by palpation in the axilla.

42 Radiographs (b): A second radiographic projection is essential if the diagnosis is in doubt. Note that if the humeral head has minimal medial displacement the AP view may appear normal. (This is especially the case in posterior shoulder dislocations.) The most useful additional projection is the axial lateral (sometimes called the tangential lateral). (Illus.: the normal appearances in such films.) In recurrent dislocation especially this view may show a defect in the posterior aspect of the humeral head (see Frame 69).

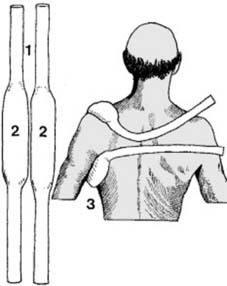

44 Radiographs (d): If the shoulder is too painful to allow an axial lateral, obtain an apical oblique projection; the landmarks are similar to those seen in the AP, but may be easier to interpret. Alternatively, if the patient is not overweight, a translateral projection, at right angles to the plane of the AP, may be helpful. This view is often difficult to interpret, but note that in the normal shoulder (Illus.) the posterior border of the humerus and the axillary border of the scapula form a shallow parabolic curve (see also Frame 61).

45 Radiographs (e): An associated fracture of the greater tuberosity is not uncommon (see Frame 36 for mechanism). This does not influence the initial treatment of the dislocation by reduction, but may require subsequent attention. The radiographs of an acute dislocation may show evidence of previous episodes, the presence of a Hill Sachs lesion being particularly suggestive even although this may occasionally be found after a first dislocation.

51 Alternative methods of reduction: In this common and generally easy to reduce dislocation there is no shortage of alternative procedures. These include the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

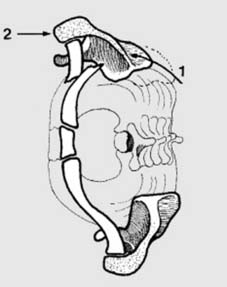

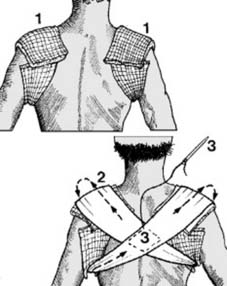

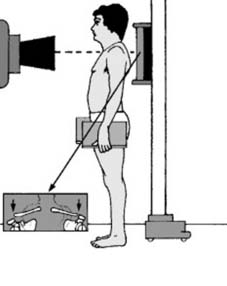

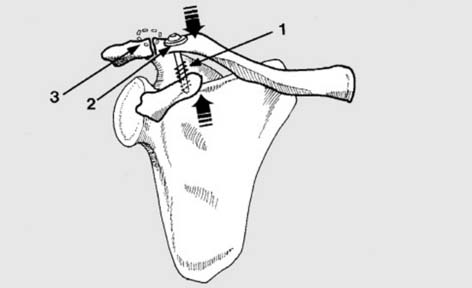

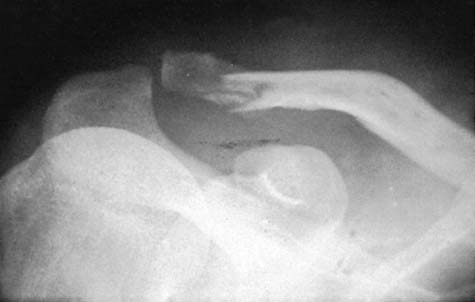

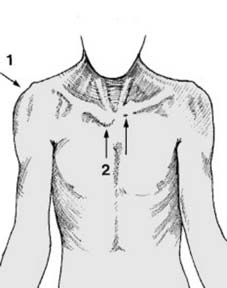

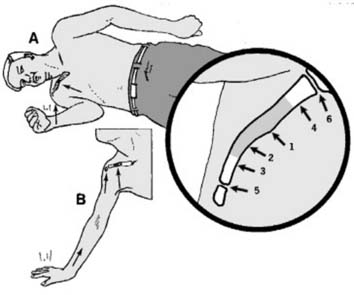

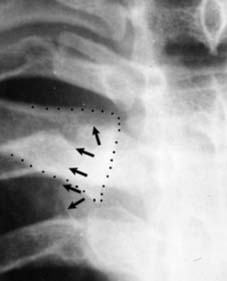

Full access? Get Clinical Tree