The shoulder

Edmund M. Kosmahl

Introduction

Shoulder pain and dysfunction are common problems for seniors. The prevalence of musculoskeletal shoulder complaints ranges from 14.3% to 32.0% (Satish et al., 2001; Chaaya et al., 2012), with 21% reporting bilateral symptoms. Shoulder disorders are associated with substantial functional limitation, because functional limitation is correlated with pain during active shoulder motion (Ozaras et al., 2009). Important activities such as feeding, dressing and personal hygiene can be compromised. Pain and shoulder mobility restrictions are significantly associated with long-term decreases in quality of life measures (Nesvold et al., 2011).

Because shoulder impairment and pain can produce functional limitation, tests and measures of pain, impairment and functional limitation should be incorporated in the examination of the aging shoulder. Visual analog scales are valid and reliable measures of pain (Bergh et al., 2000). The Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (Bicer & Ankarali, 2010) and the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Outcome Questionnaire (Slobogean et al., 2010) are measures of shoulder function for which validity and reliability have been established. The purpose of this chapter is to review rehabilitation concepts for the following shoulder problems that may cause pain and dysfunction in seniors: (1) degenerative rotator cuff; (2) fracture of the proximal humerus; (3) arthroplasty; and (4) shoulder pain with hemiplegia.

Degenerative rotator cuff

The rotator cuff is comprised of the musculotendinous insertions of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis muscles. These structures are important for nearly all shoulder functions, especially activities that require overhead arm function. Rotator cuff pathology is the most common affliction of the adult shoulder (Akpinar et al., 2003).

Advancing age is the factor most highly correlated with degenerative tendinopathy of the rotator cuff (Feng et al., 2003). A lifetime of activity can lead to degeneration of the rotator cuff in association with osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral and acromioclavicular joints. Degeneration can cause partial- or full-thickness tears in the cuff.

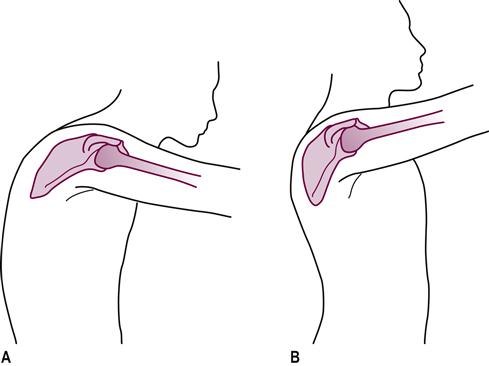

Degeneration of the rotator cuff can be associated with subacromial impingement syndrome. The mobility of the thoracic spine and scapulae is decreased in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome (Seitz et al., 2012). Theoretically, subacromial impingement can be induced by excessive thoracic kyphosis and protracted scapulae (Lewis et al., 2005; Kalra et al., 2010). These postural misalignments place the glenoid and acromion in a downward and forward position. This position may encourage subacromial impingement when the arm is elevated (Fig. 20.1; see Chapter 15 Posture). When range of motion (ROM) limitations and postural malalignments are present, interventions should include exercises to increase mobility and establish a more upright posture.

Exercises for degenerative rotator cuff should be designed to avoid worsening a subacute inflammatory process. The therapist should incorporate exercises to avoid positions that cause subacromial impingement and pain. Table 20.1 summarizes rehabilitation interventions for degenerative rotator cuff without tear.

Table 20.1

Interventions for degenerative rotator cuff

| Impairment | Intervention |

| Pain and inflammation | Rest, modalities (cold, nonthermal ultrasound, electrical stimulation) |

| Excessive thoracic kyphosis and limited mobility | Thoracic spine extension exercises |

| Protracted scapulae and limited mobility | Scapular retraction exercises |

| Decreased shoulder ROM | Passive and assisted ROM exercises (assistance from noninvolved upper extremity, overhead pulley, wand) |

| Decreased strength of shoulder musculature | Isometrics, side-lying isotonics for internal and external rotators, assisted eccentric lowering of arm from overhead |

| Decreased function | Gradual introduction: touch top of head, back of neck, low back – adapt activities of daily living to functional capabilities |

When tear of the degenerative rotator cuff exists, the history and presentation are typical. The patient usually does not report trauma. A common scenario involves the sudden inability to raise the arm overhead during a functional activity. Pain may or may not be reported. The patient cannot hold the arm in the 90° abducted position (failure of the drop-arm test). Because of the poor condition of the degenerative tissues, operative repair for tears of the rotator cuff is less often considered for older persons. Surgical repair produces less satisfactory outcomes in persons older than 65 years (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011a). The metaphor of ‘trying to anastomose cooked spaghetti’ may be helpful to conceptualize the rationale for nonoperative management of degenerative rotator cuff tear.

The success of nonoperative management for rotator cuff tear is associated with the initial amount of ROM and strength (Tanaka et al., 2010). For this reason, it is unreasonable to expect full functional return for the patient with degenerative rotator cuff tear who cannot actively raise the arm above the head at initial evaluation. Management should be aimed at decreasing inflammation and pain (when present), maintaining full passive ROM, and maximizing strength and functional ability. The interventions summarized in Table 20.1 are appropriate for the patient with degenerative rotator cuff tear. Because the restoration of full, active, overhead mobility is less likely for these patients, assisted ROM exercises often must be continued indefinitely. This is important to prevent additional pathology, such as adhesive capsulitis.

Fracture of the proximal humerus

Seventy-five percent of proximal humerus fractures occur in older persons (Chu et al., 2004), and of these, 75% occur in women. Low bone mass, falls and frailty are risk factors. Ninety-two percent of proximal humerus fractures are the direct result of a fall. These realities suggest that screening and intervention for fall risk, frailty and bone health are worthwhile preventive measures, and should be part of a comprehensive rehabilitation program after proximal humeral fracture.

Most fractures at the proximal humerus are nondisplaced or minimally displaced and can be managed nonoperatively (Bell et al., 2011). Management involves a period of sling immobilization followed by early ROM exercises. The sling is worn when not exercising. There is no clear consensus regarding the length of time for immobilization prior to initiating exercises. Starting exercise earlier can reduce pain and improve shoulder activity (Bruder et al., 2011). Although initial formation of bone callus takes about 3 weeks, there is evidence that mobilization at 1 week instead of 3 weeks alleviates short-term pain without compromising long-term outcome (Handoll & Ollivere, 2010). One should expect loss of function of the joint capsule and muscles about the shoulder during the period of immobilization. This is a function of fibrous adhesions that may develop in response to bleeding in the capsule.

The exercise program should begin with active-assistive motion within pain tolerance (Hodgson et al., 2003). It is unwise to apply passive stretching until there is radiographic evidence of fracture union (usually about 6 weeks). Resistance exercises should be avoided during this period. Isometric exercises may be considered from the time of injury provided there is no risk of displacement of the fracture fragments by muscular contraction. This is a concern whenever the fracture involves the greater or lesser tuberosities. Sub-maximal isometric exercise may be appropriate to encourage muscle contractility without risking displacement of fracture fragments. An outline of general exercise interventions for nonoperative proximal humeral fracture appears in Table 20.2.

Table 20.2

Exercise interventions for proximal humeral fracture (non-operative)

| Problem | Exercise | Timeline |

| Maintain or improve ROM | Assisted ROM (wand, wall climbing, pendulum) | 7–14 days, or radiographic evidence of callous (usually 3 weeks) |

| Passive ROM, stretching (overhead pulley) | Radiographic evidence of union, usually 6 weeks | |

| Maintain or improve strength | Submaximal isometrics | No risk of fragment displacement, usually immediately |

| Full active ROM against gravity | Radiographic evidence of union, usually 6 weeks | |

| External resistance isotonics | Ability to perform full active ROM against gravity, radiographic evidence of union, usually 6 weeks | |

| Maximize function | Touch top of head, back of neck, low back | Assisted – radiographic evidence of callous, usually 3 weeks Unassisted – radiographic evidence of union, usually 6 weeks |

About 15% of fractures of the proximal humerus involve displacement of fragments that is greater than 1 cm or angulation of fragments that is more than 45°. The four important fracture fragments are: (1) humeral head; (2) greater tuberosity; (3) lesser tuberosity; (4) humeral shaft. These fractures usually require operative reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) to allow fracture healing and return of function. More serious fractures can interrupt the blood supply to the humeral head. This interruption can lead to necrosis, which may require hemiarthroplasty.

Rehabilitation following ORIF varies depending on the classification of the injury (see Table 20.3) and stability of fixation. Close communication with the surgeon can facilitate proper progression of the rehabilitation program without risking a delay in healing or re-injury. Some older patients may not be candidates for ORIF because they cannot reasonably be expected to tolerate (or survive) anesthesia. In other cases, osteoporosis may reduce bone stock to the point where hardware fixation cannot be achieved. Complete restoration of function may be an unrealistic goal for these patients. In the past decade, locking plate technology has been used to achieve stable fixation of fractures in spite of weakened osteoporotic bone (Cornell & Omri Ayalon, 2011). Every attempt should be made to maximize functional outcomes (e.g. dressing and grooming).

Table 20.3

Neer classification for proximal humeral fractures

| Category | Description |

| I One-part | Non- or minimally displaced |

| II Two-part | One part displaced>1 cm or angulated>45° |

| III Three-part | Two parts displaced and/or angulated from each other, and from remaining part |

| IV Four-part | Four parts displaced and/or angulated from each other |

| V Fracture-dislocation | Displacement of humeral head from joint space with fracture |

Adapted from Neer CS II. Displaced proximal humeral fractures: I. Classification and evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg 1970;52A:1077.

Shoulder arthroplasty

Shoulder arthroplasty options include total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), stemmed hemiarthroplasty, resurfacing arthroplasty and reverse TSA (American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 2011b). Table 20.4 contains details about these surgical procedures.

Table 20.4

Shoulder arthroplasty surgical procedures

| Procedure | Surgery Details | Indications | Other |

| Total shoulder arthroplasty | Humeral component: metal stem and ball, may be cemented Glenoid component: plastic cup, usually cemented | Osteoarthritis with intact rotator cuff | Better pain relief than hemiarthroplasty |

| Stemmed hemiarthroplasty | Humeral component only: metal stem and ball, may be cemented | Arthritis or severe fracture involving only the humerus (glenoid cartilage intact) Severely weakened glenoid bone Arthritis with severe rotator cuff tendon tear | Less pain relief than total shoulder arthroplasty |

| Resurfacing arthroplasty | Humeral component only: cap prosthesis resurfaces humerus (no stem) | Glenoid cartilage intact No humeral fracture Preserve humeral bone | Reduced risk of component wear and loosening Easier to convert to total shoulder arthroplasty in future |

| Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty | Humeral component: plastic cup on metal stem Glenoid component: metal ball | Cuff tear arthropathy (arthritis with complete tear of rotator cuff, inability to elevate arm above 90°) Revision of failed total shoulder arthropathy | Reversal of components moves center of rotation giving deltoid a better mechanical advantage to elevate arm |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree