Abstract

Objective

To assess the prognostic implications of the 6-minute walk test (6-MWT) distance measured twice, one year apart, in a large sample of patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) followed for an extended period (> 8 years from baseline).

Material and methods

Patients undertook a 6-MWT at baseline and at one year, and were followed up for 8 years from baseline.

Results

Six hundred patients (median [inter-quartile range, IQR]) (age 78 [72–84] years; 75% males; body mass index 27 [25–31] kg·m −2 ; left ventricular ejection fraction 34 [26–38] %) were included. At baseline, median 6-MWT distance was 232 (60–386) m. There was no significant change in 6-MWT distance at one year (change −12 m; P = 0.533). During a median follow-up of 8.0 years in survivors, 396 patients had died (66%). Four variables were independent predictors of all-cause mortality in a multivariable Cox model (adjusted for body mass index, age, QRS duration, left ventricular ejection fraction); increasing NT pro-BNP, decreasing 6-MWT distance at 1 year, decreasing haemoglobin, and increasing urea.

Conclusions

Distance walked during the 6-MWT is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with CHF. In survivors, the 6-MWT distance is stable at 1 year. The 6-MWT distance at 1 year carries similar prognostic information.

Résumé

Objectifs

Évaluer la valeur pronostique de la distance parcourue lors du test de marche de 6 minutes (TDM6), mesurée deux fois à un an d’intervalle auprès d’un large échantillon de patients insuffisants cardiaques suivis au long terme (> 8 ans après inclusion).

Patients et méthode

Les patients passaient un TDM6 à l’inclusion et un an après et étaient suivis pendant 8 ans après le début de l’étude.

Résultats

Six cent patients (médianes : [écart interquartile, EI]) (âge 78 [72–84 ans] ; 75 % hommes ; indice de masse corporelle (IMC) 27 [25–31] kg·m −2 ; fraction d’éjection ventriculaire gauche 34 [26–38] %) ont été inclus. À l’inclusion, la distance médiane du TDM6 était de 232 (60–386) m. Aucun changement significatif de la distance parcourue lors du TDM6 était noté à un an (changement −12 m ; p = 0,533). Lors du suivi médian de 8 ans dans cette cohorte, 396 patients sont décédés (66 %). Une analyse multivariée selon le modèle de régression de Cox (ajusté pour l’IMC, âge, durée du complexe QRS, fraction d’éjection ventriculaire gauche) révèle que quatre variables sont des facteurs prédictifs indépendants de mortalité (toutes causes confondues) : augmentation des concentrations du marqueur cardiaque NT pro-BNP, diminution de la distance parcourue lors du TDM6 à un an, baisse de l’hémoglobine et augmentation de l’urée.

Conclusion

La distance parcourue lors du TDM6 est un facteur prédictif indépendant de la mortalité toutes causes confondues chez les patients insuffisants cardiaques. Dans cette population, la distance parcourue lors du TDM6 reste stable à un an. La distance parcourue lors du TDM6 à un an garde la même valeur prédictive de mortalité.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) is perhaps the “gold standard” method for assessing exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF), but it is not widely available. More simple tests of functional capacity are commonly used . The distance walked during a six-minute walk test (6-MWT) is reproducible and sensitive to changes in quality of life . It is a self-paced, sub-maximal test, and exercise intensity mimics activities of daily living in patients with mild-to-moderate CHF . The 6-MWT can be affected by a number of factors including: severity of heart failure, extent of co-morbidities , verbal encouragement provided by the healthcare professional , track layout, and the number of walk tests performed and their proximity to each other .

We have previously showed agreement between repeated 6-MWTs (12 months apart) in 74 patients with HF with unchanged symptoms (intra-class correlation coefficient = 0.80; 95% CI = 0.69–0.87) . However, in practice, symptoms and functional capacity may change over time. Studies suggest that 6-MWT distance increases with repeat testing . This “learning effect” is likely to be affected by changes in symptoms and medication usage but also other factors such as patient motivation, familiarity with the test requirements, and psycho-social factors (including confidence and anxiety levels) .

The prognostic implication of 6-MWT distance from repeated tests is unclear. The aim of the present study was to assess the prognostic implications of 6-MWT distance measured twice, one year apart, in a large sample of patients with CHF followed for an extended period (> 8 years from baseline).

1.2

Methods

The Hull and East Riding Ethics Committee approved the study, and all patients provided informed consent for participation. Clinical information obtained included past medical history and drug and smoking history. Clinical examination included assessment of body mass index (BMI), heart rate, rhythm, and blood pressure (BP). Heart failure was defined as current symptoms of heart failure, or a history of symptoms controlled by ongoing therapy, in the presence of reduced left ventricular (LV) systolic function on echocardiography and in the absence of any other cause for symptoms . 2D-echocardiography was carried out by one of three trained operators. LV function was assessed by estimation on a scale of normal, mild, mild-to-moderate, moderate, moderate-to-severe, and severe impairment. LV ejection fraction (LVEF) was calculated using the Simpson’s formula, where possible, from measurements of end-diastolic and end-systolic volumes on apical 2D views, following the guidelines of Schiller et al. and LVSD was diagnosed if LVEF was < 45%.

The 6-MWT was conducted following a standardised protocol . A 15 m flat, obstacle-free corridor, with chairs placed at either end was used. Patients were instructed to walk as far as possible at a self-selected pace, turning 180° every 15 m in the allotted time of 6 minutes. Patients were able to rest, if needed, and the time remaining was called every second minute . Patients were excluded if they were unable to walk without assistance from another person (not including mobility aids), or if they were unable to exercise because of non-cardiac limitations. Patients walked unaccompanied so as not to influence walking speed. After 6 minutes, patients were instructed to stop and the total distance covered was measured to the nearest metre. Standardised verbal encouragement was provided to patients at 2 minutes and 4 minutes in a neutral tone. If a patient could not undertake the 6-MWT, a distance of 0 m was recorded. The 6-MWT was repeated 12 months later.

1.3

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as medians with inter-quartile ranges (IQR); categorical data as percentages. Continuous variables were assessed for normality by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. NT pro-BNP was normalised by log-transformation for analysis. No survivor was followed for fewer than 8 years from baseline. We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to assess the relation between variables at baseline and survival at 8 years from baseline, and report the area under the curve (AUC) with 95% confidence intervals (CI), sensitivity, specificity, and optimal cut-points. To define the optimal cut-point, we used the point closest to the upper left corner of the ROC curve, often known as the (0, 1) criterion.

Cox regression models (univariable and multivariable) were used to develop predictor models using all baseline variables. We used multivariable Cox proportional hazards model using the backward likelihood ratio method ( P value for entry was < 0.05; P value for removal > 0.1) to identify independent predictors of all-cause mortality from candidate predictor variables. The assumption of proportionality was tested for each variable using the method of Grambsch and Therneau . To minimise the risk of ‘overfitting’, we were guided by Peduzzi et al. who suggested an events per variable ratio of 10:1. To determine the robustness of our model(s), we performed bootstrapping based on 1000 stratified samples. SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, New York, USA) was used to analyse the data. An arbitrary level of 5% statistical significance was used throughout (two-tailed). We followed the guidance of Perneger and did not adjust for multiple testing in order to avoid the inflation of type I error. The primary outcome measure was all-cause mortality.

1.4

Results

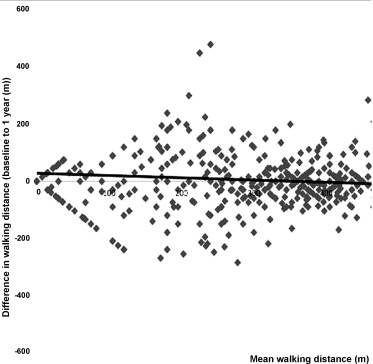

Six hundred patients (median [inter-quartile range, IQR]) (age 78 [72–84] years; 75% males; body mass index 27 [25–31] kg·m −2 ; left ventricular ejection fraction 34 [26–38]%) with heart failure due to left ventricular systolic impairment were included in the study ( Table 1 ). At baseline, median 6-MWT distance was 232 (60–386) m, and quartile ranges for 6-MWT distance were < 60 m, 61–270 m, 271–365 m, and > 365 m. After a median follow-up of 374 (21–45) days, the 6-MWT was repeated and walking distance was unchanged (change −12 m; P = 0.533). Fig. 1 shows limits of agreement for difference in walking distance between baseline and one year (y = −0.0784 × +27.663; R 2 = 0.0068; P = 0.657). During a median follow-up of 8.0 years in survivors, 396 patients had died (66%).

| Variables | Patients |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 77.8 (71.5–83.6) |

| Males (%) | 75 |

| BMI (kg·m −2 ) | 27.3 (24.6–31.1) |

| NYHA class | |

| I/II | 76 |

| III/IV | 24 |

| LVEF (%) | 34 (26–38) |

| FEV 1 /FVC (%) | 80 (70–90) |

| Resting HR (beats·min −1 ) | 70 (60–82) |

| Resting systolic BP (mmHg) | 133 (117–150) |

| Resting diastolic BP (mmHg) | 76 (68–86) |

| QRS duration (ms) | 110 (96–139) |

| Haemoglobin (g·dL −1 ) | 13.7 (12.5–14.8) |

| Log NT pro-BNP | 7.0 (6.0–7.9) |

| Sodium (mmol·L −1 ) | 140 (138–141) |

| Potassium (mmol·L −1 ) | 4.4 (4.1–4.7) |

| Urea (mmol·L −1 ) | 6.8 (5.2–9.1) |

| Creatinine (u·moL −1 ) | 106 (88–127) |

| Diuretic (%) | 84 |

| ACE-inhibitor (%) | 74 |

| Beta-blocker (%) | 67 |

| Spironolactone (%) | 20 |

| Baseline 6-MWT (m) | 232 (60–386) |

Ten variables were significantly associated with all-cause mortality following the one-year test in univariable Cox analysis ( Table 2 ) including baseline 6-MWT distance (χ 2 = 61.1; P < 0.0001) and 1-year 6-MWT distance (χ 2 = 59.5; P < 0.0001). After bootstrapping, 11 variables remained statistically significant ( Table 3 ) including baseline 6-MWT and 1-year 6-MWT distance.

| Variables | P value | HR | 95% CI | Chi 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Log NT Pro-BNP | < 0.0001 | 1.60 | 1.48 | 1.73 | 140.1 |

| Urea (mmol·L −1 ) | < 0.0001 | 1.09 | 1.07 | 1.11 | 78.9 |

| Haemoglobin (g·dL −1 ) | < 0.0001 | 0.78 | 0.73 | 0.83 | 68.1 |

| Baseline 6-MWT (m) a | < 0.0001 | 0.977 | 0.972 | 0.983 | 61.1 |

| 1-year 6-MWT (m) a | < 0.0001 | 0.979 | 0.973 | 0.984 | 59.5 |

| Creatinine (u·moL −1 ) a | < 0.0001 | 1.007 | 1.005 | 1.009 | 57.6 |

| Age (years) | < 0.0001 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.04 | 22.8 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | < 0.001 | 0.987 | 0.981 | 0.994 | 15.1 |

| QRS duration (m·s −1 ) | < 0.001 | 1.006 | 1.003 | 1.009 | 15.0 |

| BMI (kg·m −2 ) | 0.001 | 0.968 | 0.950 | 0.986 | 11.5 |

a HR reported for 10 unit increment; potassium, sodium, systolic BP, heart rate – not significant (not presented).

| Variables | P value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| Log NT Pro-BNP | 0.001 | 0.391 | 0.550 |

| Baseline 6-MWT (m) | 0.001 | −0.029 | −0.017 |

| 1-year 6-MWT (m) | 0.001 | −0.027 | −0.016 |

| Age (years) | 0.001 | 0.017 | 0.038 |

| Urea (mmol·L −1 ) | 0.001 | 0.067 | 0.115 |

| Haemoglobin (g·dL −1 ) | 0.001 | −0.311 | −0.195 |

| Creatinine (u·moL −1 ) | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.010 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 0.001 | −0.019 | −0.007 |

| QRS duration (m·s −1 ) | 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.009 |

| BMI (kg·m −2 ) | 0.001 | −0.052 | −0.013 |

| Sodium (mmol·L −1 ) | 0.047 | −0.057 | 0.001 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 0.316 | −0.006 | 0.002 |

| Heart rate (beats·min −1 ) | 0.461 | −0.005 | 0.006 |

| Potassium (mmol·L −1 ) | 0.579 | −0.260 | 0.134 |

All variables in Table 2 were included in a final multivariable Cox model, and four were independent predictors of all-cause mortality when adjusted for body mass index, age, QRS duration, and left ventricular ejection fraction; increasing NT pro-BNP, decreasing 6-MWT distance at one year, decreasing haemoglobin, and increasing urea ( Table 4 ). We re-ran the multivariable model by forcing baseline 6-MWT distance into it instead of 6-MWT distance at one year; we noted that the overall Chi 2 value for the model remained unchanged.

| Variables | P value | Wald | HR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Haemoglobin (g·dL −1 ) | 0.001 | 19.95 | 0.824 | 0.757 | 0.897 |

| 1-year 6-MWT (m) a | 0.001 | 10.42 | 0.988 | 0.981 | 0.995 |

| Log NT ProBNP | 0.003 | 8.74 | 1.100 | 1.005 | 1.152 |

| Urea (mmol·L −1 ) | 0.017 | 5.71 | 1.034 | 1.0006 | 1.062 |

a HR reported for 10 unit increment; model adjusted for BMI, age, QRS duration, LVEF.

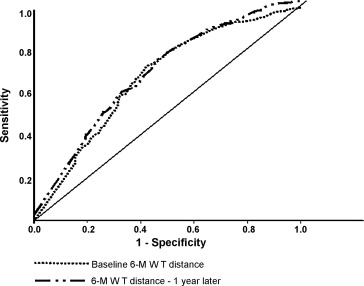

Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis of the relation between the two 6-MWT distances and all-cause mortality at 8 years from baseline is shown in Fig. 2 . For baseline distance, (AUC = 0.67; P < 0.0001; 95% CI = 0.63–0.71; the optimal cut-point for baseline 6-MWT distance was 325 m with sensitivity 0.75 and specificity 0.54); and for one year distance (AUC = 0.66; P < 0.0001; 95% CI = 0.62–0.70; sensitivity 0.73; specificity 0.53; optimal cut-point 327 m).

1.5

Discussion

We have shown that distance walked during a 6-MWT both at baseline and at one year is an independent predictor of subsequent all-cause mortality in patients with CHF. The 6-MWT distance at one year carries similar prognostic information to baseline values. We believe ours is the first study which has considered the prognostic implications of 6-MWT distance measured twice, one year apart in patients with CHF. We have shown that in survivors, the 6-MWT distance is stable at one year. There is thus little to be gained from repeating the 6-MWT at one year in clinical practice.

We have previously shown that 6-MWT distance is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality. In 1592 patients, 212 died representing a crude death rate of 13.3%. Five independent predictors of all-cause mortality were identified including decreasing 6-MWT distance . Few studies have reported serial follow up of 6-MWT distance in cardiac patients. Cheetham et al. conducted repeated 6-MWTs at baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 18 weeks in patients awaiting heart transplantation (all patients had a history of at least 6 months of symptomatic heart failure). Distance walked ranged from 457 ± 28 m to 470 ± 30 m across the four time points (greatest distance being at the second time point). Although the mean distance at each time-point was greater than in our study, the mean change of 13 m over 18 weeks was similar to our findings (−12 m), albeit over 52 weeks. Cheetham et al. did not perform a survival analysis but they concluded that the 6-MWT had limited utility in terms of repeated assessment of clinical status in patients with advanced heart failure.

Alison et al. conducted repeated 6-MWTs after 6 months in 173 patients with significant pulmonary disease, and reported a mean increase of 119 m compared to baseline. Our follow-up period was longer (1 year) and it is possible that any learning effect is lost over this period as other factors such as increasing age and severity of disease may become more significant drivers of walking performance.

The reproducibility of repeated 6-MWTs has been questioned due to inconsistencies in testing protocol. There is little agreement regarding the length or shape of the test course, whether a practice walk should be conducted, and which test result should be reported (i.e. first test, final test, best test, mean test score). Each of these issues is of particular importance when comparing serial data from multicentre trials. A 7 to 14% improvement in the second 6-MWT has been reported in patients with COPD . Sciurba et al. reported that 761 patients with severe emphysema walked further (363 m) during a second 6-MWT than during a first test one day before (343 m). They argued that this was due to patients becoming familiar with the walking course, more motivated or using better pacing strategies. Similar short-term improvement in 6-MWT distance has also been reported in older, apparently healthy individuals , and patients with heart failure .

Adsett et al. investigated whether repeated performance of 6-MWTs was related to the time interval between tests or the baseline performance in 88 patients with stable CHF. The authors reported a mean difference of 12 metres between the first and second tests and concluded that this would be clinically insignificant. Patients with a poor baseline 6-MWT distance showed no learning effect, and Adsett et al. concluded that repeated testing was unnecessary in their cohort of patients with CHF.

The optimum cut-point in our study was 325 m, patients walking less than this distance were at an increased risk of all-cause mortality. Our findings our similar to a previous study which reported a cut off < 300 m for predicting increased likelihood of death or pre-transplant hospital admission in 45 patients with more advanced heart failure than those recruited to our study.

1.5.1

Study limitations

We acknowledge that a number of confounding variables may affect performance in repeated 6-MWT over a period of 12 months including changes in lifestyle, medication usage, deterioration or improvement in symptom severity, or surgical intervention. The American Thoracic Society recommended that corridor distance should be 30 m. Our corridor was 15 m meaning that patients must turn more frequently during the 6-minute period. Therefore, the distance “norms” we report are likely to underestimate walking performance in this cohort of patients. The 6-MWT is not a test of maximal exercise capacity but is a test of submaximal exercise performance . The American Thoracic Society advocates that verbal encouragement should be limited, and tone of voice be controlled during the 6-MWT in an elderly, chronic disease population. We have followed this approach with our patients but different centres will operate different systems. Therefore, findings from our current study should not be extrapolated to other populations, or to other research centres that may use a more aggressive 6-MWT coaching style. Furthermore, patients who had a poorer 6-MWT distance may preferentially have died before the second measurement. The effect is to dilute the relation between baseline 6-MWT and outcome.

1.6

Conclusion

In survivors, the 6-MWT distance is stable at one year. Distance walked during the 6-MWT is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with CHF. The relation is similar when the test is repeated at one year, suggesting that there is limited clinical utility in repeating the 6-MWT.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

Le test cardiopulmonaire d’effort est très certainement le « gold standard » pour évaluer la capacité d’exercice du patient insuffisant cardiaque, cependant ce test n’est pas disponible dans toutes les structures. Des tests plus simples d’évaluation de la capacité fonctionnelle sont courramment utilisés . Le test de la distance parcourue pendant 6 minutes (TDM6) est reproductible et sensible aux changements de qualité de vie . Ce test d’effort sous-maximal, au rythme du patient, reflète l’intensité fournit lors des activités de la vie quotidienne des personnes ayant une insuffisance cardiaque faible à modérée . Le TDM6 peut être influencé par un certain nombre de facteurs tels que : la sévérité de l’insuffisance cardiaque, le nombre de comorbidités , l’encouragement verbal fournit par les professionnels de santé , la disposition du parcours, le nombre de tests effectués ainsi que le temps d’intervalle entre ces derniers .

Nous avons précédemment montré un lien chez 74 patients en insuffisance cardiaque entre TDM6 répétés (à 12 mois d’intervalle) et symptômes inchangés (coefficient de corrélation intra-classe = 0,80 ; 95 % IC = 0,69–0,87) . Cependant, en pratique clinique, les symptômes et la capacité fonctionnelle peuvent évoluer au fil du temps. Les études suggèrent que la distance du TDM6 augmente avec la répétition du test . Cet effet « d’apprentissage » peut être influencé par les changements de symptômes et de traitements médicamenteux mais également par d’autres facteurs tels que la motivation du patient, la familiarité avec les exigences du test et les facteurs psychosociaux (y compris les niveaux de confiance en soi et d’anxiété) .

L’impact pronostique de la distance parcourue lors de TDM6 répétés n’est pas clair. L’objectif de cette étude était d’évaluer l’impact pronostique de la distance parcourue lors du TDM6, avec deux mesures distinctes effectuées à un an d’intervalle, auprès d’une large cohorte de patients insuffisant cardiaques suivis au long-terme (> 8 ans après inclusion).

2.2

Méthodes

Le comité d’éthique de Hull et East Riding a approuvé l’étude et tous les patients ont signé un formulaire de consentement éclairé. Les données cliniques incluaient les antécédents médicaux, de tabagisme et de traitements pharmacologiques. L’examen clinique comprenait une évaluation de l’indice de masse corporelle (IMC), de la fréquence et du rythme cardiaque et de la tension artérielle (TA). L’insuffisance cardiaque était définie comme une symptomatologie observée d’insuffisance cardiaque, ou des antécédents de symptômes d’insuffisance cardiaque contrôlés par thérapie médicamenteuse, associée à la présence d’une diminution de la fonction systolique du ventricule gauche visible à l’échocardiographie et en l’absence de toute autre cause expliquant la symptomatologie . Une échocardiographie en 2D était réalisée par un des 3 techniciens d’imagerie formés à cette procédure. En fonction d’une échelle, nous avons évalué la fonction ventriculaire gauche comme normale ou entraînant une insuffisance faible, de faible à modérée, modérée, de modérée à sévère ou sévère.

Quand cela était possible, la fraction d’éjection ventriculaire gauche (FEVG) était calculée à l’aide de la formule de Simpson, basée sur les volumes télédiastolique (TD) et télésystolique (TS) mesurés sur les coupes apicales en 2D. Selon les recommandations de Schiller et al. , le diagnostic de dysfonction systolique ventriculaire gauche (DSVG) était posé quand la FEVG était < 45 %.

Le TDM6 suivait un protocole standardisé . Le parcours consistait en un couloir de 15 mètres, avec sol plat et sans obstacles, comportant des chaises placées aux deux extrémités. Les patients devaient marcher le plus loin possible à leur propre rythme, en effectuant un demi-tour de 180° tous les 15 mètres durant le temps alloué de 6 minutes. Les patients pouvaient se reposer si nécessaire, et le temps restant était énoncé à voix haute toutes les deux minutes . Les patients étaient exclus s’ils ne pouvaient marcher sans l’aide d’une tierce personne (les aides techniques étaient admises), ou s’ils ne pouvaient faire de l’exercice à cause de limitations non liées à leur état cardiaque. Les patients marchaient sans être accompagnés afin de ne pas influencer leur vitesse de marche. Après 6 minutes, les patients devaient arrêter de marcher et la distance totale parcourue était mesurée et arrondie au mètre près. Des encouragements standardisés étaient formulés d’un ton neutre à 2 et 4 minutes. Si le patient ne pouvait participer au TDM6, la distance de 0 mètre était enregistrée. Le TDM6 était répété 12 mois plus tard.

2.3

Analyse statistique

Les variables continues sont exprimées en médianes avec écart interquartile (EI) et les données chiffrées en pourcentages. Les variables continues étaient évaluées pour leur normalité à l’aide du test de Kolmogorov–Smirnov. Le NT pro-BNP était normalisé par log-transformation pour analyse. Tous les patients ont été suivis pendant 8 ans au minimum. Nous avons utilisé les courbes receiver operating characteristic (ROC) pour analyser la relation entre les variables à l’inclusion et la survie 8 ans après inclusion, nous avons rapporté les aires sous la courbe ROC avec intervalles de confiance (IC), sensibilité, spécificité et les valeurs seuils ( cut-points ). Pour définir la valeur seuil, nous avons pris le point le plus proche du coin gauche en haut de la courbe ROC, souvent appelé le critère (0, 1). Nous avons eu recours aux régressions logistiques de Cox (analyses univariée et multivariée) pour développer des modèles prédictifs en utilisant toutes les variables enregistrées à l’inclusion. À l’aide du modèle de Cox estimant le « hazard ratio » et en utilisant la méthode du rapport de vraisemblance avec sélection descendante (valeur p à l’entrée de < 0,05 ; valeur p à la soustraction de > 0,1), nous avons pu identifier des facteurs prédictifs indépendants de la mortalité toutes causes confondues à partir de variables impactant cette mortalité.

L’hypothèse de proportionnalité était testée pour chaque variable à l’aide de la méthode de Grambsch et Therneau . Pour minimiser le risque de surapprentissage ( overfitting ), nous avons suivi les recommandations de Peduzzi et al. qui suggèrent un rapport du nombre d’évènements par variable de 10:1. Pour déterminer la fiabilité de nos modèles, nous avons utilisé la méthode du bootstrap basée sur 1000 échantillons stratifiés. L’analyse des données a été faite à l’aide du logiciel SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, New York, États-Unis). Un niveau arbitraire de probabilité statistique de 5 % a été utilisé pour toutes les analyses (test à « deux queues »).

Nous avons suivi les recommandations de Perneger pour écarter une éventuelle situation d’inflation du risque alpha produite par un mécanisme de répétition, c’est-à-dire une erreur de type 1. Le principal indicateur de résultats était la mortalité toutes causes confondues.

2.4

Résultats

Six cent patients (médianes : [écart interquartile, EI]) (âge 78 [72–84 ans] ; 75 % hommes ; indice de masse corporelle (IMC) 27 [25–31] kg·m −2 ; fraction d’éjection ventriculaire gauche 34 [26–38] %) avec une insuffisance cardiaque due à une dysfonction de la fonction systolique du ventricule gauche furent inclus dans l’étude ( Tableau 1 ).