It is estimated that approximately 10-15 million or more athletes from grade school to college require preparticipation examinations (PPEs) annually in the United States (20).

No defined national standard exists for PPEs, and each state has different laws and statutes regarding them.

Ensure that athletes of all ages and skill levels are able to safely compete.

Detect any condition, medical or musculoskeletal, that may limit an athlete’s participation or require treatment, rehabilitation, or adequate control prior to participation.

Detect any condition that may predispose an athlete to injury or lead to sudden death during competition.

Meet legal or insurance requirements (49 of 50 states require yearly examinations).

Determine general health of the athlete.

Assess fitness level for specific sports.

Counsel on lifestyle issues and high-risk behaviors.

Answer health-related questions, and update vaccines.

Private office with primary care provider

Advantages: privacy, controlled environment, better continuity of care, and easier to perform counseling.

Disadvantages: higher cost, less communication with school athletic staff, and potential for providers who have insufficient knowledge and skills necessary for a complete and appropriate evaluation.

Group examination (usually done as a station-based examination)

Advantages: more cost effective, more time efficient, usually done at school with athletic staff present.

Disadvantages: lack of privacy, loud and chaotic environment thereby impairing proper cardiac auscultation, and poor follow-up.

Most states require an examination to be done yearly for high school-aged and younger athletes. However, a comprehensive exam every 2 years with yearly updates as needed is recommended by the AHA.

The National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) requires an initial complete PPE prior to participation in intercollegiate athletics, with interim annual updates of the athlete’s history. Further PPEs are not deemed necessary unless indicated by the updated history (28).

Optimal timing for the examination is at least 6 weeks before the season starts to allow sufficient time for further evaluation, treatment, and/or rehabilitation of any problems that may be uncovered.

Because the stress of sports and exercise falls primarily on the cardiovascular and musculoskeletal systems, these areas are essential for assessment as part of the PPE. This evaluation should begin with a thorough history, followed by a focused physical examination.

Close attention should also be paid to the neurologic history to specifically address concussions, stingers, and other neurologic issues.

In 1992, representatives from several national physician groups assembled to develop a comprehensive PPE tool for use among providers who perform athletic screening. Since then, there have been periodic updates.

Preparticipation Physical Examination, 4th Edition (PPE Monograph), is the most recent iteration of this work, which has been established through the collaboration of the American College of Sports Medicine®, American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM), American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM), and American Osteopathic Academy of Sports (AOASM). It can be found at http://www.ppesportsevaluation.org (1).

It is recommended that all providers use this monograph as the primary template for the PPE.

A thorough personal and family medical history has been shown to identify up to 75% of all medical problems affecting athletes (17).

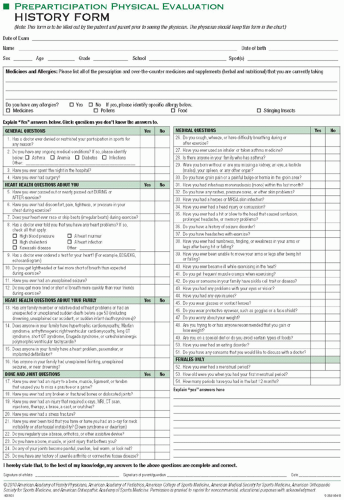

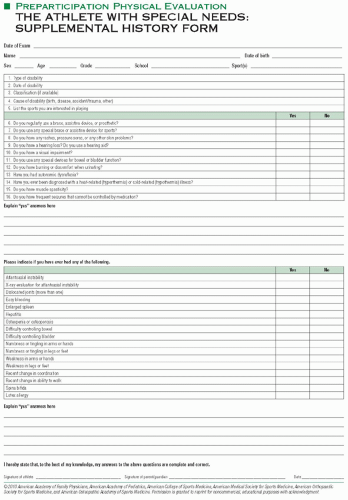

The easiest method for obtaining an athlete’s history is to use a preprinted questionnaire (such as the one available in the PPE monograph) that the parent(s) of the athlete completes prior to the examination (Fig. 17.1). The history portion of these forms is best filled out by the parents and the athlete together, because the athlete may not be fully aware of his or her complete personal and/or family history.

Key questions include asking about any major preexisting medical problems or injuries; if the athlete is taking any medicines or supplements; if the athlete has any significant environmental and/or medication allergies; and about the athlete’s current state of health.

Assess for cardiovascular risk:

Because most sudden death episodes in sports are due to cardiovascular causes, thorough cardiovascular screening is extremely important.

The relative risk for sudden cardiac death (SCD) has been found to be 2.5 times higher in athletes than in the general population (11).

The AHA has recommended eight history questions as the initial screening for cardiovascular risk.

The PPE Monograph uses those questions (see Fig. 17.1).

Positive answers to critical history questions such as “Have you ever passed out or nearly passed out DURING or AFTER exercise?” and “Have you ever had discomfort, pain, tightness, or pressure in your chest during exercise?” (Questions 5 and 6) may signal the presence of a structural heart problem.

It is also important to assess for family history of early unexplained death, cardiovascular abnormalities, or concerning signs and symptoms that may allude to possible undiagnosed cardiac abnormalities in family members.

Assess for symptoms of exercise-induced bronchospasm (EIB):

Symptoms include coughing, wheezing, and/or chest tightness during or immediately after exercise, especially in those with a personal or family history of allergic rhinitis, eczema, or asthma.

Improvement of symptoms after using an inhaled bronchodilator is highly suggestive.

Assess for concussion history:

It is important to ask about the symptoms of concussion because most who have had one may not have sought medical attention and been diagnosed.

Common symptoms include headache, nausea, dizziness, blurred vision, getting “dinged” or your “bell rung,” fatigue, either hypersomnolence or insomnia, retrograde amnesia, emotional lability, inability to concentrate in school or with homework, irritability, confusion, “not feeling right,” and “feeling like in a fog” (33,35).

□ If the patient can recall one or more of these symptoms in association with an impact to the head or body (possibly denoting a contrecoup injury), then he or she likely had a concussion.

Assess for history of repeated “stingers” and/or “burners,” which are symptoms of numbness and/or pain radiating down an arm after a blow to the head, neck, or ipsilateral shoulder; if present, they may indicate cervical stenosis or a similar condition.

Screen females for signs and symptoms related to the “female athlete triad” (disordered eating, menstrual irregularities, history of stress fractures).

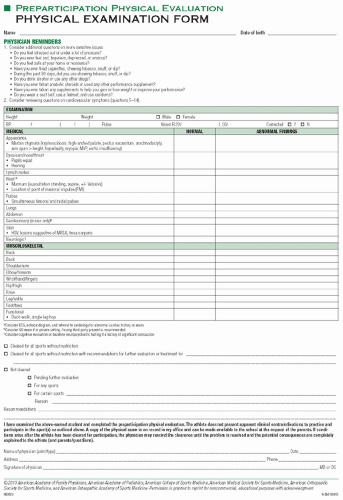

Cardiac auscultation should be done both standing and supine.

Benign systolic murmurs are common in athletes. If a murmur is grade III or louder, or diastolic, further evaluation is recommended.

The murmur associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is best heard while upright and may disappear with supine position as well as squatting.

If there is a potentially concerning murmur, having the patient perform a Valsalva maneuver can provide additional information. Typically, Valsalva will accentuate murmurs due to outflow obstruction abnormalities such as HCM.

Twenty-five percent of patients with HCM with left ventricular outflow obstruction have a murmur on physical exam (18).

Ectopic beats are also common. Those that disappear with exercise are usually benign, while those brought on with exercise are more worrisome. Ventricular ectopy in young athletes should also raise suspicion for possible use of stimulants (e.g., cocaine).

Simultaneous palpation of the radial and femoral pulses for asymmetry is a simple screen for coarctation of the aorta.

Readings that indicate hypertension vary for different age ranges and between genders (34). Three separate elevated blood pressure (BP) readings are needed to diagnose hypertension (8,34).

Hypertension in children and adolescents is based off of percentiles for each age according to gender and height; those with repeated measurements at or above the 95th percentile are considered hypertensive (34).

Those between the 90th and 95th percentiles are deemed “high normal,” or the equivalent of the adult prehypertensive.

In people age 18 and over, the definitions of hypertension are as follows (8):

Prehypertension: systolic blood pressure (SBP) between 120 and 139 mm Hg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) between 80 and 89 mm Hg.

Grade I hypertension: SBP between 140 and 159 mm Hg or DBP between 90 and 99 mm Hg.

Grade II hypertension: SBP ≥ 160 mm Hg or DBP ≥ 100 mm Hg.

Those who have prehypertension or grade I hypertension without evidence of end-organ damage need not be restricted from competitive sports.

Grade II hypertensives should be restricted from high static sports (e.g., weightlifting) until their BP is controlled.

Systolic hypertension in young athletes is frequently related to anxiety or inappropriate cuff size in husky individuals.

If the initial measurement is high, it is recommended that another reading be taken after resting for 5 minutes.

It is not necessary to perform a comprehensive joint-by-joint musculoskeletal exam on all PPEs.

The “2-minute musculoskeletal examination” can be a useful screen (Table 17.1).

Look for preexisting injuries, because they are likely to recur. The knees, shoulders, and ankles are most at risk.

Focus more of your examination on problem areas if they exist.

Keep in mind the demands of the particular sport the athlete will be playing, and focus more on areas of the body that will be under stress and prone to injury from that sport.

Table 17.1 The 2-Minute Musculoskeletal Examination for Screening Athletes During the Preparticipation Examination

Instructions

Observation

Stand facing examiner

Acromioclavicular joints, general habitus

Look at ceiling, floor, over both shoulders; touch ears to shoulders

Cervical spine motion

Shrug shoulders (examiner resists at 90 degrees)

Trapezius strength

Abduct shoulders 90 degrees (examiner resists at 90 degrees)

Deltoid strength

Full external rotation of arms

Shoulder motion

Flex and extend elbows

Elbow motion

Arms at sides, elbows 90 degrees flexed; pronate and supinate wrists

Elbow and wrist motion

Spread fingers; make fist

Hand or finger motion and deformities

Tighten (contract) quadriceps

Symmetry and knee effusion; ankle effusion

“Duck” walk four steps (away from examiner with buttocks on heels)

Ability to perform this rules out significant hip and knee abnormalities

Back to examiner

Shoulder symmetry, scoliosis

Knees straight, touch toes

Scoliosis, hip motion, hamstring tightness

Raise up on toes, raise heels

Calf symmetry, leg strength

SOURCE: Smith NJ. Sports Medicine: Health Care for Young Athletes. Evanston (IL): American Academy of Pediatrics; 1983. 1 p.

Musculoskeletal problems found during the PPE should be treated with appropriate rehabilitation and conditioning programs prior to returning to activity.

Height/weight

Eating disorders, ideal body weight

General appearance

Stigmata of Marfan disease: kyphoscoliosis

Eyes

Vision

Pupils for the presence of anisocoria, which may be present in up to 10% of patients.

Ears/nose/throat

Lungs

Abdominal

Hepatosplenomegaly, masses

Skin

Infectious diseases, acne

Neurologic

Genitourinary

Single testicle, hernia, testicular mass

Tanner staging to assess physical maturity is no longer recommended.

Consensus is that laboratory tests should not be done routinely during the PPE.

Consider routine hematocrit in female athletes, especially those involved in endurance sports.

Perform cholesterol testing if indicated by history.

Consider testing for sickle cell trait (SCT). The NCAA now requires testing for all Division I athletes in which the presence of SCT is unknown. However, individual athletes can opt out of testing if they prefer (28).

Consider formal neuropsychological testing if there is a history of multiple concussions, prolonged postconcussion symptoms, or inconsistent or significantly diminished school performance (see Chapter 26).

EIB appears to be much more prevalent in endurance athletes (27).

If there is concern for EIB, it is recommended to perform testing to confirm or rule out the condition, because it has been shown that the correlation between symptoms and actual disease is poor (7,16,32) (see Chapter 24).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree