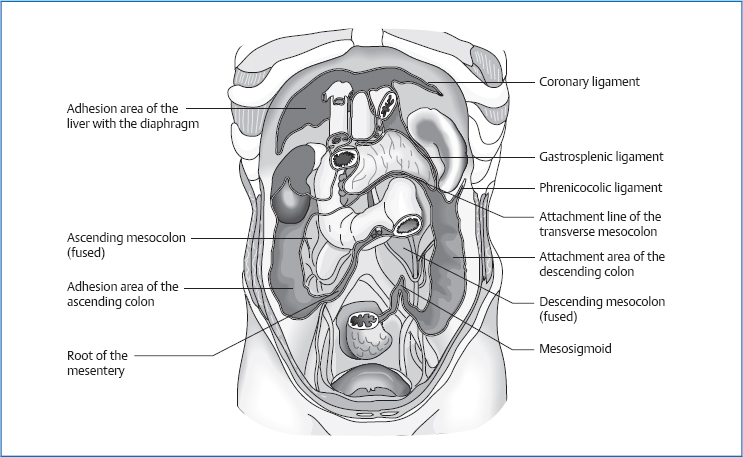

11 The Peritoneum The visceral peritoneum lies (firmly) against the inside of the parietal peritoneum and the surfaces of the abdominal organs. Fig. 11.1 Structures of the parietal peritoneum on the posterior wall of the torso. The peritoneum is topographically connected to all the intraperitoneal organs and to most of the retro- and extraperitoneal organs and structures. The mesenteries attach the organs to the walls of the torso and supply them with vessels and nerves. Gastropancreatic fold (with left gastric artery) with the duodenopancreatic ligament (with common hepatic artery) The mesoappendix originates in the mesentery and continues into the appendico-ovarian ligament. The transverse mesocolon divides the peritoneal space into the upper and the lower abdomen. The ligament of Treitz (suspensory muscle of the duodenum) runs from the crus of the diaphragm, the right edge of the esophagus, and the aortic hiatus to the duodenojejunal flexure. The Treitz fascia constitutes the connection of the duodenum and the pancreas. In addition, it fixates the pancreas posteriorly onto the transversal fascia. The Toldt fascia connects the ascending colon with the descending colon. Both fasciae are the rudimentary embryonic mesenteries of these organs and point to their embryonic intraperitoneal location. Ligaments connect two organs to each other or an organ to the wall of the abdomen, but do not contain important vessels. They include the: The omenta are infoldings of the peritoneum that sometimes contain vessels and run from one organ to another. They include the: The arterial, venous, and lymphatic circulations of the visceral peritoneum correspond to the supply lines of the organ. The parietal peritoneum is supplied segmentally. The peritoneum is supplied by sensory and vasomotor fibers from the phrenic nerve and the thoracic and lumbar segmental nerves. As the parietal peritoneum is attached to the wall of the torso (see above), movements of the torso cause it to move as well, in the sense of stretching or approximating partial areas, e. g., if you lean the upper body backward, the anterior part of the peritoneum, which lies flat against the abdominal wall, is stretched. If postoperative adhesions are present, this can trigger pain. A lateral flexion of the torso to the right approximates the right lateral part and stretches the left lateral part. The engine for this form of movement is the respiratory movement of the abdomen and diaphragm. During inhalation, the respiratory movement in the diaphragm causes the entire peritoneal sac to shift caudally. In addition the subdiaphragmatic parts experience a shift medially in the lateral areas. The abdominal wall is pushed anteriorly by the abdominal organs during inhalation; the peritoneum follows similarly. During exhalation, the opposite movement occurs. If the peritoneum is not affected by dysfunctions, it carries out a rotation around a longitudinal axis. The right side rotates toward the right and the left side toward the left. Functions of the peritoneum and the greater omentum are:

Anatomy

General Facts

Function

mechanical protection by means of impact-buffering fat

mechanical protection by means of impact-buffering fat

vascular function

vascular function

immune defense

immune defense

Location

Parietal Peritoneum

diaphragmatic part: underside of the diaphragm

diaphragmatic part: underside of the diaphragm

posterior part:

posterior part:

anterior part: covers the anterolateral abdominal wall and forms:

anterior part: covers the anterolateral abdominal wall and forms:

inferior part: lines the sidewalls of the pelvic cavity and lies along the median line of the subperitoneal connective tissue. In the female pelvis, the peritoneum forms two deep pouches:

inferior part: lines the sidewalls of the pelvic cavity and lies along the median line of the subperitoneal connective tissue. In the female pelvis, the peritoneum forms two deep pouches:

Visceral Peritoneum

Topographic Relationships

Attachments/Suspensions

Mesenteries

Mesentery of the Stomach

Mesentery of the Small Intestine

12–15cm long and 18mm wide

12–15cm long and 18mm wide

crosses L2–L5

crosses L2–L5

At the level L3–L4, the superior mesenteric vein enters the mesentery.

At the level L3–L4, the superior mesenteric vein enters the mesentery.

Between L4 and L5, the mesentery crosses the right ureter.

Between L4 and L5, the mesentery crosses the right ureter.

Transverse Mesocolon

Sigmoid Mesocolon

One root runs vertically downward from the inferior mesenteric artery to S3.

One root runs vertically downward from the inferior mesenteric artery to S3.

The second root of the sigmoid mesocolon runs diagonally from the inferior mesenteric artery to the inner edge of the left psoas.

The second root of the sigmoid mesocolon runs diagonally from the inferior mesenteric artery to the inner edge of the left psoas.

Additional connections exist to the left iliac artery, left fallopian tube, and mesentery.

Additional connections exist to the left iliac artery, left fallopian tube, and mesentery.

Ligaments

round ligament of the liver (ligamentum teres hepatis, obliterated umbilical vein)

round ligament of the liver (ligamentum teres hepatis, obliterated umbilical vein)

coronary ligament with left and right triangular ligaments

coronary ligament with left and right triangular ligaments

gastrophrenic ligament (enveloping fold of the two leaves of the peritoneum that cover the stomach)—continues as the lesser omentum and gastrosplenic ligament

gastrophrenic ligament (enveloping fold of the two leaves of the peritoneum that cover the stomach)—continues as the lesser omentum and gastrosplenic ligament

broad ligament of the uterus (fixates the peritoneum firmly to the uterus and adnexas)

broad ligament of the uterus (fixates the peritoneum firmly to the uterus and adnexas)

phrenicocolic ligament (lateral continuation of the greater omentum)

phrenicocolic ligament (lateral continuation of the greater omentum)

Omenta

lesser omentum

lesser omentum

greater omentum (a part of the greater omentum forms the gastrocolic ligament)

greater omentum (a part of the greater omentum forms the gastrocolic ligament)

gastrosplenic ligament (continuation of the gastrocolic ligament in a left-lateral direction)—continues on the inside of the spleen and as the anterior leaf of the pancreaticosplenic ligament

gastrosplenic ligament (continuation of the gastrocolic ligament in a left-lateral direction)—continues on the inside of the spleen and as the anterior leaf of the pancreaticosplenic ligament

pancreaticosplenic ligament (posterior short leaf continues as the posterior parietal peritoneum)

pancreaticosplenic ligament (posterior short leaf continues as the posterior parietal peritoneum)

Omental Bursa

Borders

at the back: posterior parietal peritoneum

at the back: posterior parietal peritoneum

at the front: lesser omentum, stomach, transverse colon

at the front: lesser omentum, stomach, transverse colon

below: transverse mesocolon

below: transverse mesocolon

on the left: gastrosplenic and pancreaticosplenic ligaments

on the left: gastrosplenic and pancreaticosplenic ligaments

Circulation

Innervation

Movement Physiology according to Barral

Motricity

Mobility

Motility

Physiology

mechanical protection of the anterior abdominal wall

mechanical protection of the anterior abdominal wall

immunological function by embedding numerous lymphatic cells and vessels, especially in the greater omentum

immunological function by embedding numerous lymphatic cells and vessels, especially in the greater omentum

Fat storage: the greater omentum can store considerable amounts of fat which could even cause a significant increase in abdominal pressure, with dysfunctions of the abdominal organs or diaphragm.

Fat storage: the greater omentum can store considerable amounts of fat which could even cause a significant increase in abdominal pressure, with dysfunctions of the abdominal organs or diaphragm.

Pathologies

Symptoms that Require Medical Clarification

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree