Chapter 11 The pelvis, hip and femoral neck

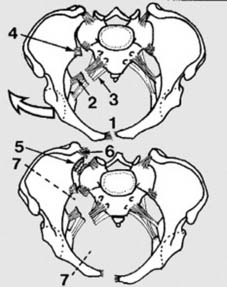

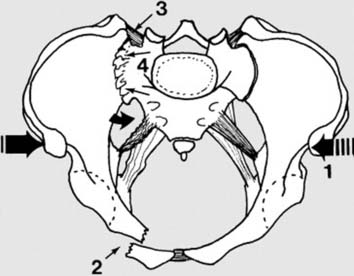

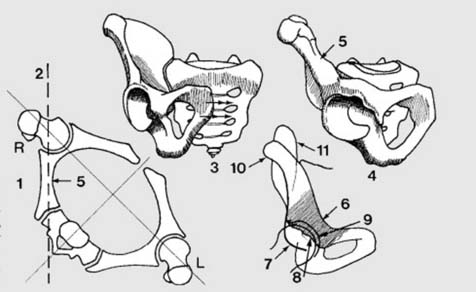

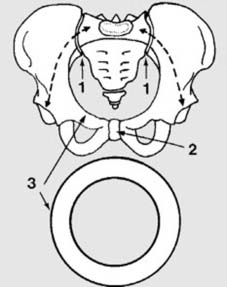

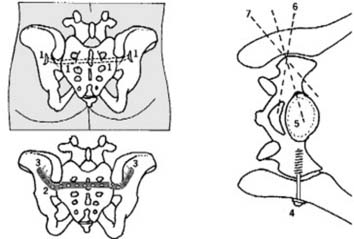

1 General principles(a): The two wings of the pelvis are joined to the sacrum behind (1) by the very strong sacroiliac ligaments. In front they are united by the symphysis pubis (2). This arrangement forms a cylinder of bone, the pelvic ring (3), which protects the pelvic organs and transfers the body weight from the spine to the limbs. (The dotted line indicates the path of weight transfer.)

7. Summary of treatment guidelines: There are two clear issues involved in the management of any major pelvic fracture:

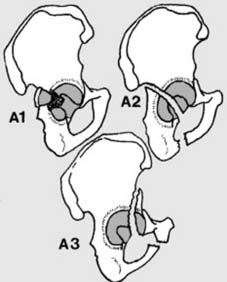

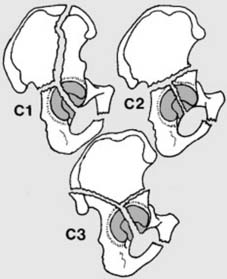

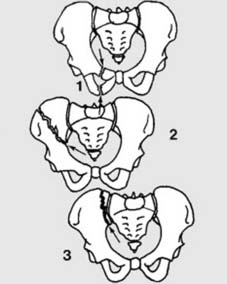

A1 and A2: (Tile’s Classification):

IP and DT:Conservative treatment may be followed in the majority of cases.

IP:apply a pelvic binder or external fixator

IP:use an external fixator or pelvic binder if the patient is haemodynamically unstable.

IP:external fixator (and if necessary a pelvic clamp) plus skeletal leg traction.

DT:internal fixation (e.g. by application of reconstruction plates).

12 A2: Minimally displaced, stable fractures of the pelvic ring (c): Other fractures of this type include: (1) fractures of two rami on one side; (2) fracture of the ilium running into the sciatic notch; (3) fracture of the ilium or sacrum involving the sacroiliac joint. The nature of these injuries often suggests at least momentary involvement elsewhere in the ring: nevertheless, assuming that they are uncomplicated, they may be treated as in the previous frame.

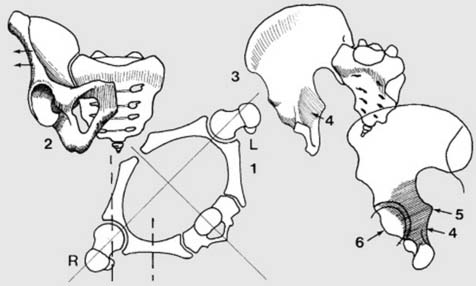

17 Pelvic compression and stabilisation (a): A pelvic binder may be quickly and easily applied in the emergency room. It is slipped under the pelvis (which is then manually compressed) before fastening it in front. The London Splint (illustrated) uses a single Velcro fastener. Other binders include the Dallas Pelvic Binder and the Geneva Belt. (Note they are not suitable for prolonged use.) If any of these devices are applied before radiographs are taken they may mask the extent of the pathology.

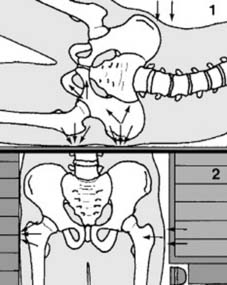

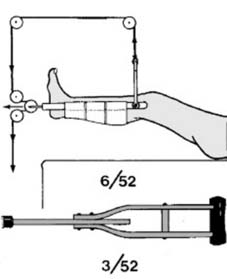

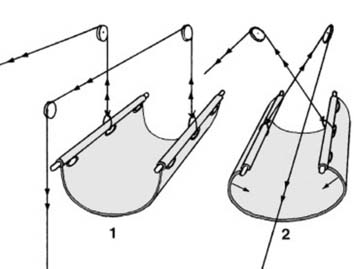

21 Pelvic compression and stabilisation (d): If the patient is not haemodynamically unstable, immediate and definitive conservative treatment is also possible using a canvas pelvic sling. The upper edges of the sling are reinforced with steel rods and eyelets, and it may be padded with wool prior to being positioned under the pelvis. Weights in the order of 4–8 kg are applied through pulleys in a Balkan beam (1), resulting in an inward thrust on the sides of the pelvis. If check radiographs show the reduction is incomplete, the weights may be increased or the traction cords crossed (2). The treatment should be continued for 6 weeks, taking the usual precautions over skin care; weight bearing can generally be allowed after 8 weeks.

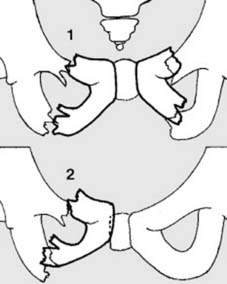

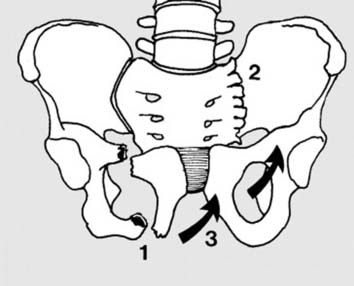

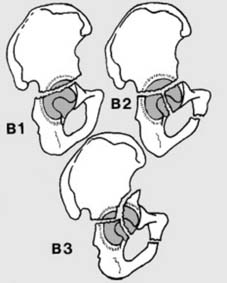

25 Contralateral compression injuries (bucket handle fractures) (B3): Two rami fracture (1) opposite the posterior injury (2) (or there is a butterfly fracture). The hemipelvis rotates (3), causing leg shortening without vertical migration. The majority are stable so that in most no fixation is needed. As in the previously described B2 cases, an external fixator may be used to control any frank instability or considered as suitable for dealing with leg shortening in excess of 1.5 cm. An external fixator will be required in any case where there is haemodynamic instability, multiple injuries or difficulty in pain control. Later, internal fixation should be considered where there is symphyseal separation or marked pelvic asymmetry.

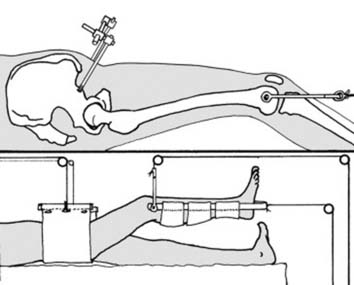

28 Rotationally and vertically unstable injuries (c): Initial treatment (IP): These serious injuries are often associated with life-threatening internal haemorrhage and other complications. In the initial stages, prompt application of an external fixator and skeletal traction may be sufficient to control blood loss, but in some cases a C-clamp (see next frame) or other measures (see Frame 35) will be required. Prior to surgery, or if surgery is considered inadvisable, control rotational instability with an external fixator, pelvic binder or canvas sling, and proximal migration of the hemipelvis with skeletal traction (up to 20 kg) applied through a supracondylar or tibial Steinman pin.

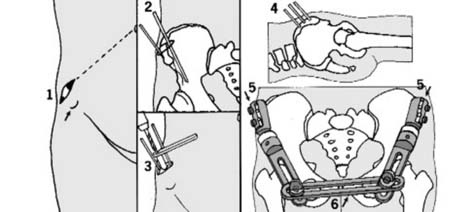

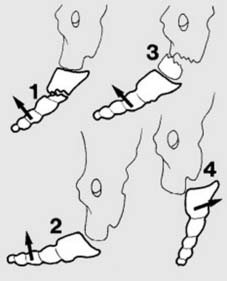

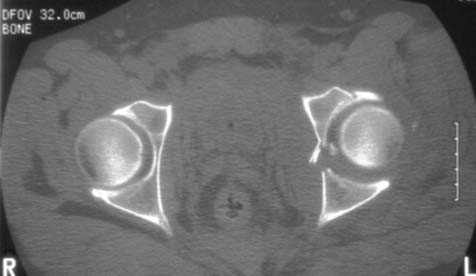

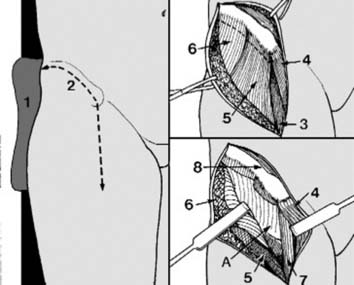

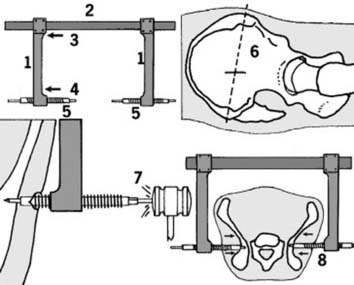

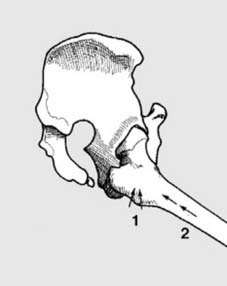

29 The anti-shock pelvic C-clamp (a): This consists of side arms (1) which can be moved freely along a cross bar (2) when pressure is applied proximally (3), but lock when subjected to any distal force (4). Hollow bolts (5) which screw into the side arms are designed to carry Steinman pins. Method of application:make a skin incision on each side approximately 6 cm or so from the posterior superior iliac spine, on a line connecting the posterior superior iliac spine with the anterior superior iliac spine (6), and slide the sidearms until the threaded bolts enter the wounds. Anchor each bolt by hammering a Steinman pin a depth of 1 cm into bone (7). Bring the bolts into contact with the pelvis by approximating the side arms with pressure from above. Tightening the bolts with a spanner will now close the S-I joints (8).

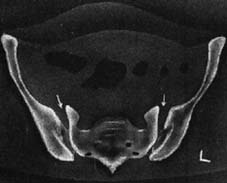

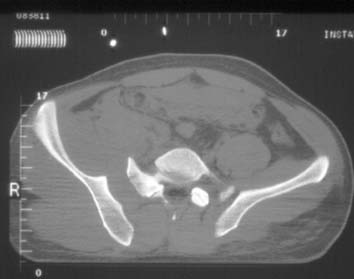

33 The anti-shock pelvic C-clamp (e): In this case, application of a C-clamp successfully stabilised both the sacroiliac joints and the haemodynamic instability. (Note in the scan only the tips of the screws are showing in the plane of the cut.)

35 Definitive treatment (c):Local posterior approaches may be employed to treat dislocations of the sacroiliac joint, and fractures of the sacrum in Type C injuries. A tension plate may be used: this is inserted through two small incisions (1) and a tunnel in the soft tissues made from below one posterior superior iliac spine to the other. The plate can be pre-bent to fit (2). Three cancellous screws should then be placed in each ilium (3), directed away from the sacroiliac joints and the dangerous area of the sacral ala (the lateral sacral masses).(d): The sacroiliac joint may be stabilised by screws running into the lateral ala (4). The position and direction of these screws must be determined with the greatest care, and it is advisable to visualise the ala directly and to use an image intensifier. In some cases, however, it is possible to carry out the procedure percutaneously, using guide wires and cannulated screws (as in Frame 32). (e): Where the sacrum is fractured, fixing screws must engage the body of the sacrum (5) to obtain the necessary purchase. Again the utmost care must be taken to avoid broaching the sacral canal (6) or entering the pelvis anteriorly (7). Formal posterior approaches (e.g. Kochers’s) may be needed in acetabular reconstructions where there is involvement of the posterior column. Note: In Type C3 injuries the acetabulum takes priority.

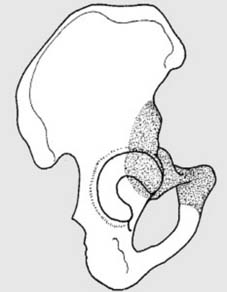

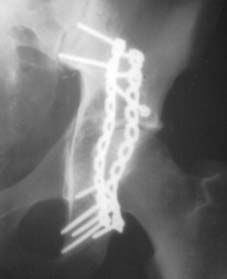

Type C3 Injuries: Definitive treatment (a):In Type C3 injuries the acetabulum takes priority in the assessment and in any proposed reconstruction. (See also Frame 43 et seq.) The radiograph shows a type C3 pelvic injury. There is a widely displaced pubic symphysis, a fracture of the left superior pubic ramus, and a disruption of the left sacroiliac joint. There is a transverse fracture of the right acetabulum, and a dislocation of the right hip. This injury was treated initially with an external fixator and a manipulative reduction of the hip.

37 Type C3 Injuries: The urinary tract required investigation and a retrograde urethrogram was performed. This showed an intact urethra and normal bladder filling without spillage. (Illus.)

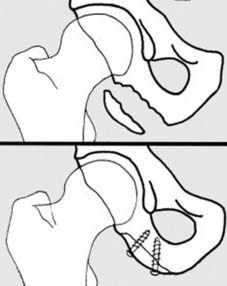

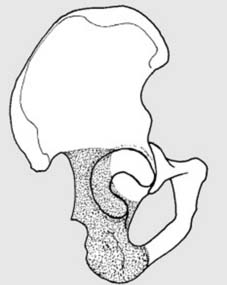

43 Fracture of the acetabulum/central dislocation of the hip: In this group of injuries the pelvis is fractured as a result of force transmitted through the femoral head. This may occur from a blow or fall on the side (1) or when force is transmitted up the limb (2) via the foot, as in a fall from a height or through the knee as in a car dashboard injury.

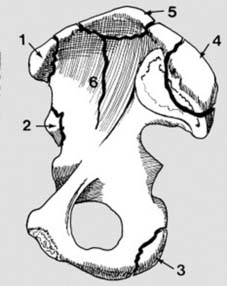

48 Is the posterior column intact? (a): The posterior column stretches upwards from the ischial tuberosity to the sciatic notch, and includes the posterior part of the acetabular floor. To clarify this a second oblique projection is often helpful (three-quarter external oblique projection).

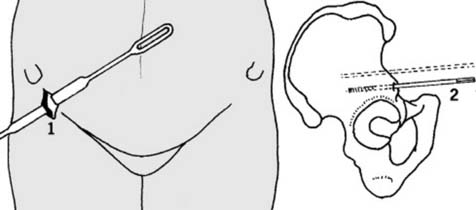

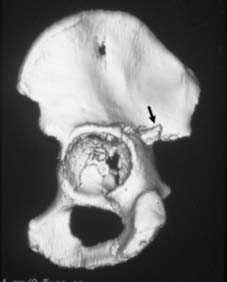

52 (c): A 3-D reconstruction of the previous case confirms the degree of comminution of the acetabular floor. This also shows with great clarity a backward projecting spike of bone in the region of the greater sciatic foramen. (This was held responsible for an accompanying sciatic nerve palsy, and was removed at open operation, during which internal fixation was carried out.) You may now be in a position to relate your findings to the AO Classification of acetabular fractures.

B1: transverse fracture with or without involvement of the posterior acetabular wall.

B3: a vertical fracture added to the transverse fracture involves the anterior column.

58 TREATMENT(c): GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Open reduction of acetabular and pelvic fractures is seldom easy. An extensive exposure is always required, and attendant haemorrhage is a common problem. There is often great difficulty in obtaining a substantial improvement in the position of the bone fragments and in subsequently holding them, so that operating time can be very long, increasing the risks of infection and delayed wound healing. There is the danger of exacerbating or producing sciatic nerve problems and of causing heterotopic ossification, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, or chondrolysis of the hip. Such surgery may be contraindicated in the elderly, obese or the unfit. In children and adolescents open reduction is rarely indicated and then not always rewarding. As these fractures are of highly vascular cancellous bone, the vigorous processes of repair may render reduction impossible if surgery is delayed for much longer than a week or so.

EXPOSURES

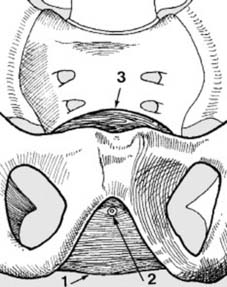

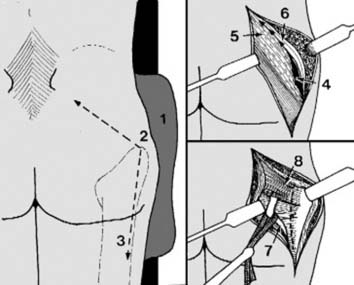

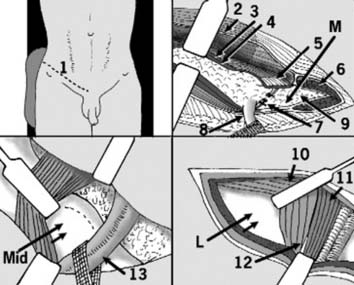

In the ilio-inguinal approach, one or more of three so-called windows may be used to gain bony access. The patient is supine with a sandbag under the buttock. The incision (1) is made parallel to the inguinal ligament and 2 cm above it; it may extend to the midline in front. Posteriorly it may be continued 2 cm above the anterior two-thirds of the iliac crest. The aponeurosis of external oblique (2) is divided along the line of its fibres. The wound is deepened by incising internal oblique (3), transversus (4), their conjoint tendon (5), and the ipsilateral part of rectus femoris (6) in the same line. The inferior epigastric vessels (7), of varying anatomical position, are divided and ligated. The spermatic cord (8) is isolated, taped and retracted laterally. Extra peritoneal fat (9) and the bladder are eased away from the area of the symphysis and superior pubic ramus. This is the medial window (M).

59 COMPLICATIONS OF PELVIC FRACTURES

1 HAEMORRHAGE

(See Frame 16 for a summary of this complication and its management.) Substantial internal haemorrhage is common, particularly where there is disruption of the pelvic ring and proximal migration of the hemipelvis (Type C injuries), but may complicate less major injuries. Shock must be anticipated in all but the most minor of fractures. (See pp 32–34 for details of the management of major fluid loss.)

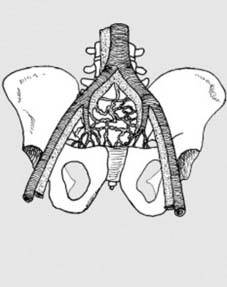

In the uncommon case of a severe retroperitoneal haemorrhage, where in spite of a massive transfusion programme losses continue to gain over replacement, exploration may have to be reconsidered. It is seldom that a single bleeding source can be found, the haemorrhage generally arising from massive disruption of the pelvic venous plexus; then, packing of the wound for 48 hours may give control. Occasionally successful results have also been claimed from ligation of one or both internal iliac arteries.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

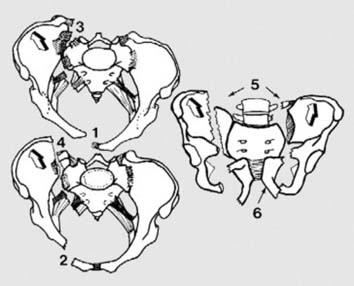

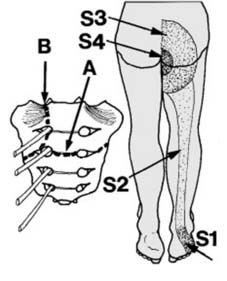

Full access? Get Clinical Tree