26 The paediatric spine and neuromuscular conditions

Cases relevant to this chapter

Essential facts

1. Idiopathic scoliosis is the commonest spinal deformity in children; it is usually painless and most commonly affects adolescents.

2. Congenital scoliosis is due to failure of formation and/or segmentation of the spine.

3. Painful scoliosis needs to be investigated for an underlying cause.

4. Neuromuscular scoliosis usually produces a long ‘C’-shaped collapsing thoracolumbar curve with associated pelvic obliquity.

5. Persistent back pain in children is uncommon and requires further investigation.

6. An infant may be floppy at birth because of a central neurological problem or acute illness, such as infection or hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy.

7. Any boy not walking by 18 months or with global developmental delay or with delayed speech development should have creatine kinase levels checked for a diagnosis of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

8. The three main causes of cerebral palsy are abnormalities of brain growth and development, brain damage, and impaired brain function.

9. Spasticity is the commonest tone abnormality in cerebral palsy.

10. With better nutrition, treatment of chest infections and overall care, even children with severe cerebral palsy and profound learning difficulties are likely to survive into adult life.

Paediatric spine

Scoliosis

Idiopathic scoliosis

Clinical presentation and prognosis

Infantile idiopathic scoliosis

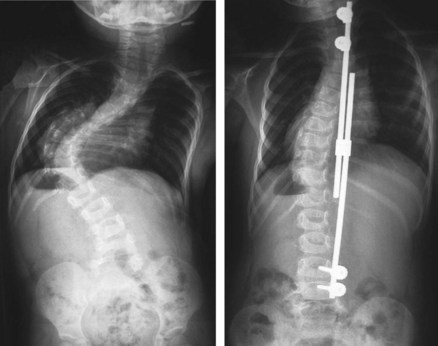

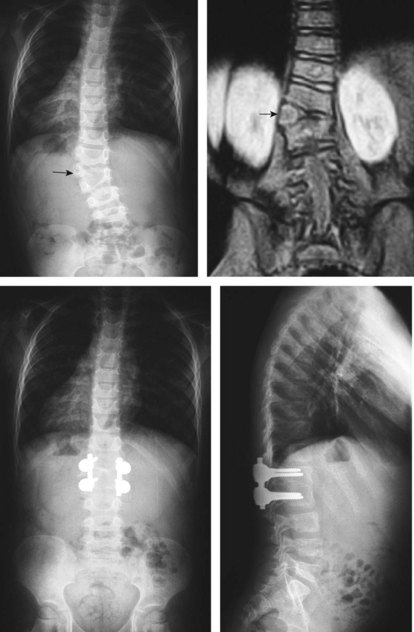

This has two distinct patterns of development. Some 80–90% of curves resolve spontaneously with further growth and do not require treatment other than observation. The remaining 10–20%, however, show rapid progression, are usually resistant to conservative management with a spinal jacket or a brace, and require early surgical treatment. Male and female patients are equally affected. Surgical treatment is indicated in older children with progressive curves or in children with more severe deformities where the use of growing rods can delay spinal fusion for a later age and preserve spinal growth (Fig. 26.1). If left untreated, infantile scoliotic curves will exceed 100° by the age of 10 years and patients can die from cor pulmonale in early adulthood.

Clinical approach

The history of a cosmetically obvious rib asymmetry is highly suggestive of a thoracic scoliosis. Idiopathic scoliosis is not usually associated with back pain and, if children present with spinal pain and/or a stiff back, other causes for the scoliosis, such as an infection, spinal cord tumour, spinal dysraphism, spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis and a herniated intervertebral disc (see Red flag symptoms, Chapter 1), should be considered.

Radiographic evaluation

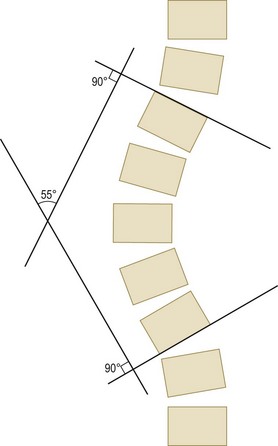

Obtain antero-posterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the spine with the patient standing to document the type and location of the scoliosis. The magnitude of the curve can be measured using the Cobb method in both the coronal (frontal) and the sagittal (lateral) planes of the spine (Fig. 26.2).

Treatment

The aim of management of scoliosis is to ensure that a child does not enter adulthood with a significant curve (Table 26.1). Observation is indicated for growing patients with small adolescent idiopathic scoliotic curvatures of up to 20–25°, a minimal cosmetic deformity and otherwise normal findings on clinical examination.

Table 26.1 Guidelines for treatment for patients with an adolescent idiopathic scoliosis

| Magnitude of Curve (°) | Treatment |

|---|---|

| <20–25 | Observation |

| 25–40 | Bracing |

| >40–50 | Surgical correction and fusion with instrumentation and bone graft |

Bracing with a lightweight, detachable, custom-moulded, underarm orthosis can be used in a growing child who has a moderate curve ranging from 20–25° up to 40° and whose apex lies below the level of the sixth thoracic vertebra. The aim of a brace (see Chapter 7) is to modify spinal growth and stop curve progression. Brace management cannot lead to resolution of the scoliosis and, at best, will maintain the size of deformity seen at the initiation of bracing. Therefore, the indication for bracing is for small-to-moderate curves that are cosmetically acceptable at the time of initial diagnosis. The child is asked to wear the brace for approximately 20 hours a day until skeletal maturity. Compliance can be a significant problem.

Surgical correction should be considered if the curve is greater than 40° and likely to deteriorate with remaining spinal growth, or if there is an established scoliosis greater than 50°. The aim of surgery is to prevent further deterioration by stabilizing the spine and to correct all the components of the deformity (spinal curvature, rib prominence, shoulder or waistline asymmetry, thoracic translocation and listing of the trunk). This can be achieved with the use of spinal instrumentation and bone grafts to produce a solid bony arthrodesis (fusion) across the instrumented levels (Fig. 26.3). The general principle when selecting the extent of the fusion is to try to maintain as many mobile segments as possible to preserve spinal flexibility.

Congenital scoliosis

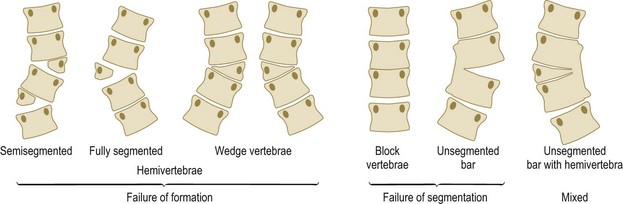

Congenital scoliosis is caused by developmental vertebral anomalies that occur in the mesenchymal period, during the first 6 weeks of intrauterine life, and produce a lateral longitudinal imbalance in the growth of the spine. Although the vertebral anomalies are present at birth, the clinical deformity may not become evident until later childhood. The anomalies can affect any part of the spine and are classified as defects of vertebral formation or vertebral segmentation, and mixed anomalies (Fig. 26.4). These malformations often cause a structural deformity in one or two planes and a progressive curvature as the spine grows. As the child grows, a structural compensatory scoliosis often develops above or below the congenital scoliosis, and creates a more significant imbalance of the spine.

Congenital scoliosis is usually progressive and does not respond to conservative management. It is impossible to create growth on the concavity of the scoliosis where it is either retarded or non-existent due to malformation, and the aim of surgery is to balance spinal growth by stopping the accelerated growth on the convexity of the curve. The key to successful treatment is early diagnosis while the curve is still small and there is an opportunity to balance the growth of the spine prophylactically (Fig. 26.5). If the patient presents with a more severe deformity at a later stage, salvage surgery will be required and usually involves an extensive spinal arthrodesis and a suboptimal outcome.

The spine in spina bifida (myelomeningocele)

There is a spectrum of spinal abnormalities that may include any of the following:

These anomalies may produce a kyphosis (paralytic or congenital), a lordosis (secondary to hip flexion contractures), a scoliosis (usually paralytic but also as a result of mixed paralytic and congenital curves) or a combination of deformities affecting both the coronal and the sagittal planes of the spine. Bracing is not effective in controlling paralytic curves and is also hampered by insensate skin, because the cord abnormality produces a lower motor neurone lesion. Spinal fusion is indicated where there is increasing spinal deformity to produce a stable posture for sitting and standing, to relieve bony prominences that may cause skin-pressure problems and to improve respiratory function. See page 335 for further discussion of spina bifida.

Neuromuscular scoliosis

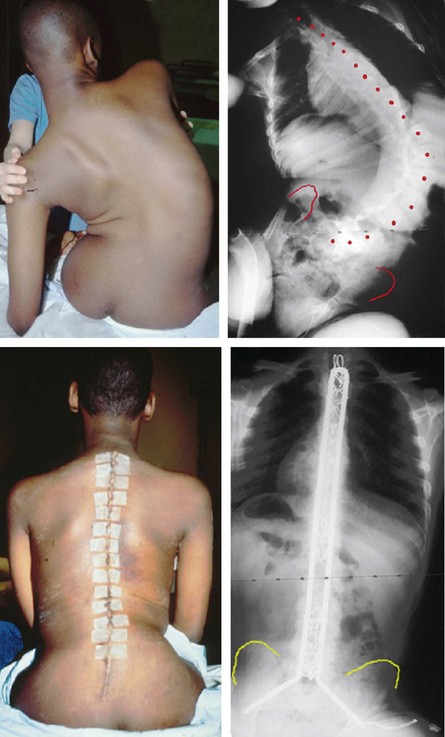

Neuromuscular scoliosis occurs in patients with upper or lower motor neurone lesions, and in muscular conditions (Table 26.2). The spinal deformity is the consequence of a generalized muscle weakness affecting the trunk, with or without associated spasticity, and the effect of gravity. This type of scoliosis is typically characterized by an early onset with rapid progression and a poor response to orthotic management, particularly during the adolescent growth spurt. The scoliosis that develops is a long ‘C’-shaped curve with the apex most frequently located in the thoracolumbar spine, and can occasionally be associated with an increased kyphosis or lordosis. The curve commonly extends to the pelvis causing marked pelvic obliquity.

Table 26.2 Incidence of neuromuscular conditions associated with scoliosis

| Condition | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

| Cerebral palsy | 25 |

| Myelomeningocele | 60 |

| Spinal muscular atrophy | 67 |

| Freidrich’s ataxia | 80 |

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | 90 |

| Spinal cord injury in children (before age 10 years) | 100 |

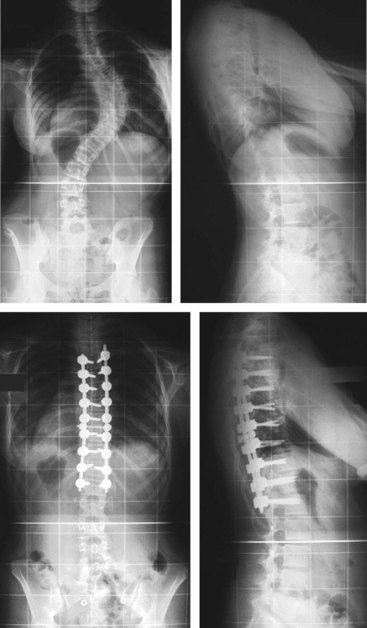

The management of neuromuscular scoliosis is directed at maintaining or improving functional abilities and the quality of life. Bracing may provide trunk support and improve posture, but does not prevent curve progression. Seating can be adapted to accommodate the spinal deformity, but also does not correct the deformity. Trunk support and seating modifications can be used as a temporizing measure to maintain function in young children with flexible deformities, to allow further spinal growth and delay surgery. Spinal fusion is the only treatment that is effective in these patients and involves an extensive spinal arthrodesis with instrumentation and allograft bone. It is indicated to improve seating stability, maintain function, improve the quality of life and prevent cardiorespiratory compromise (Fig. 26.6). A multidisciplinary approach is essential when surgical treatment is anticipated to reduce the significant risks of potentially life-threatening complications that can occur in the perioperative period.

Kyphosis and lordosis

In the lateral (sagittal) plane, kyphosis is a forward bend of the spine and lordosis is a backward bend of the spine. The spine has a physiological kyphosis in the thoracic and a lordosis in the cervical and lumbar spines (Box 26.1). The normal thoracic kyphosis should not exceed 40–50° and the normal lumbar lordosis should be up to 60°.

Scheuermann’s disease (juvenile kyphosis) is characterized by at least three contiguous anteriorly wedged vertebrae and affects boys more than girls. The cause of the condition is largely unknown and should be differentiated from a postural (roundback) kyphosis where there are no structural abnormalities. If the Scheuermann’s deformity is severe and creates back pain that is refractory to conservative measures, surgery to straighten and fuse the spine may be indicated (Fig. 26.7).

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree