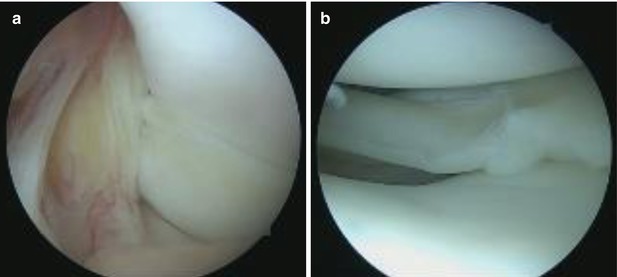

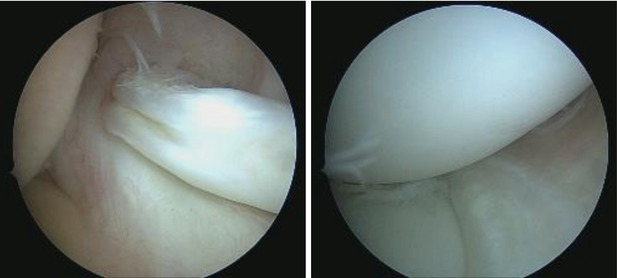

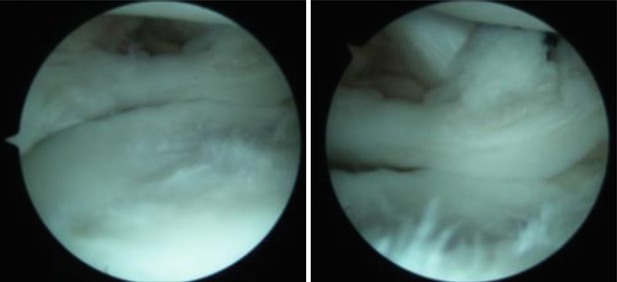

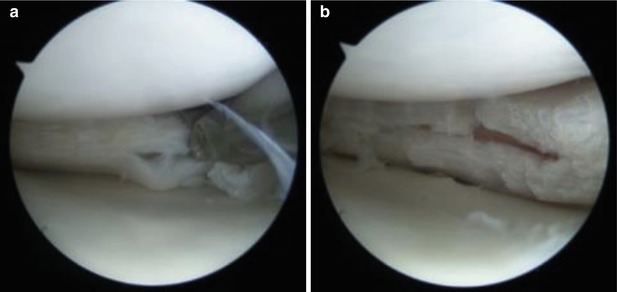

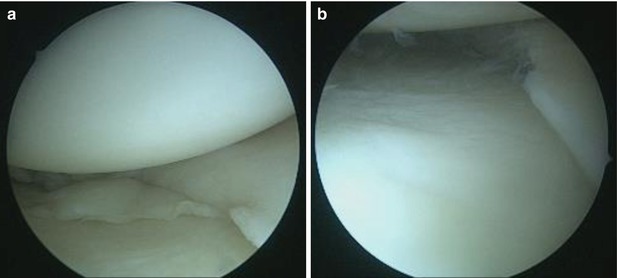

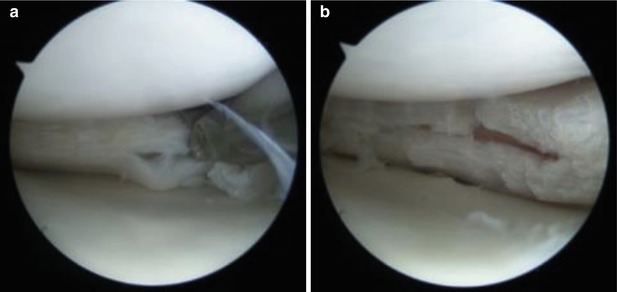

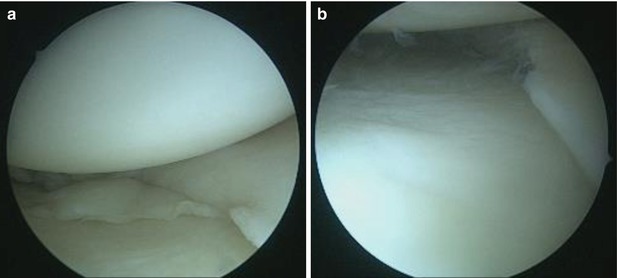

Fig. 2.1

Occult lesion of the medial meniscus. The femoral surface can be viewed with no lesions (a). Longitudinal meniscal rupture on the tibial aspect (b)

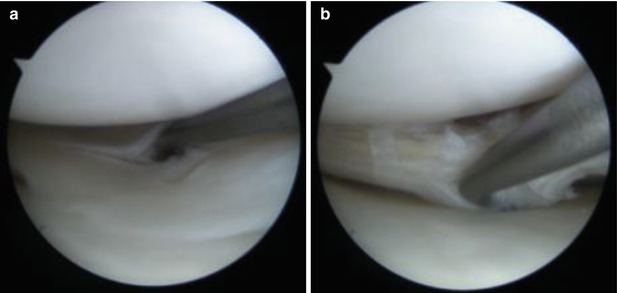

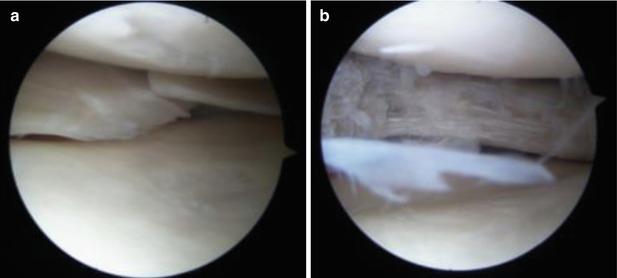

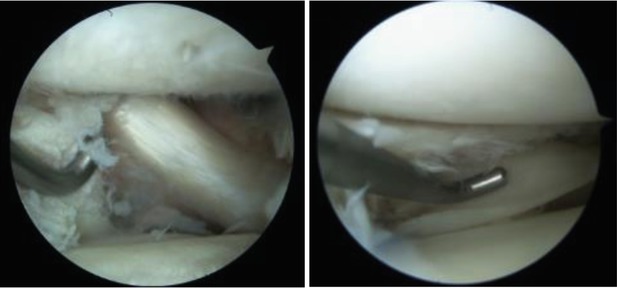

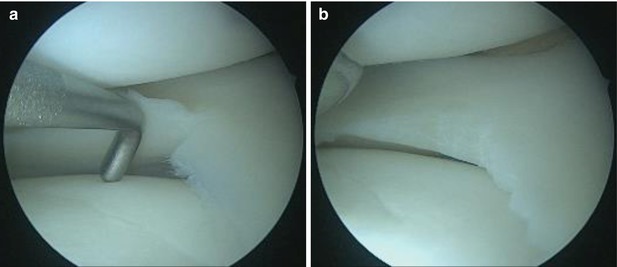

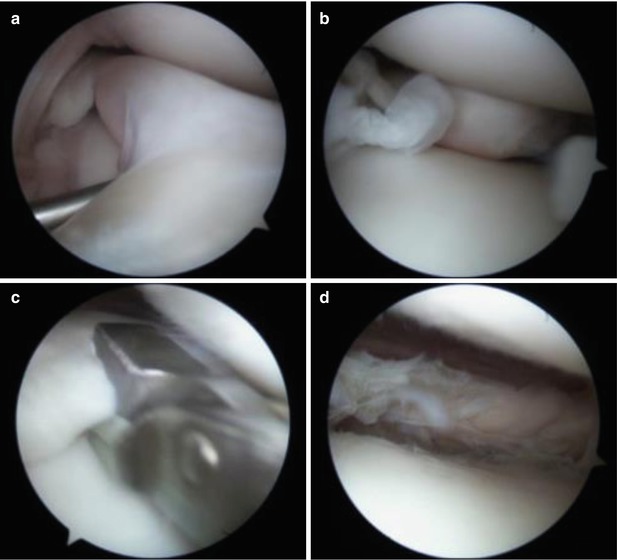

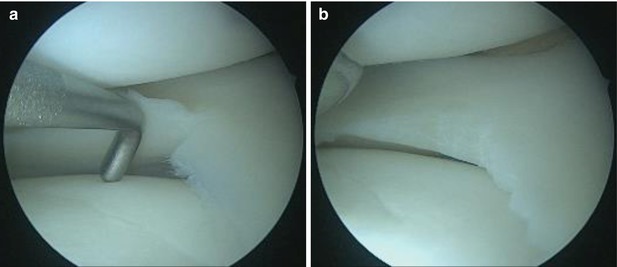

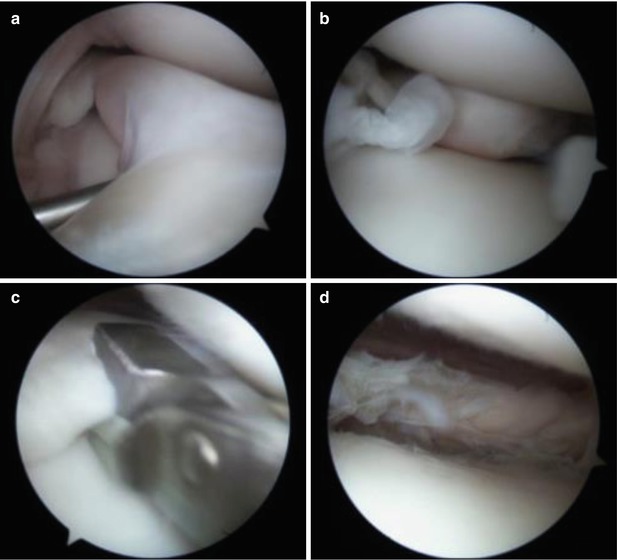

Fig. 2.2

Apparently an incomplete longitudinal rupture of the medial meniscus (a). Upon further inspection the full extent of the rupture can be seen expanding further (b)

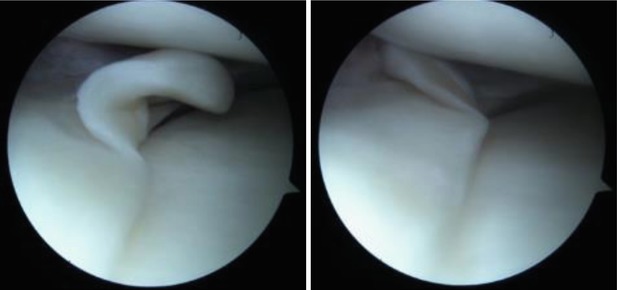

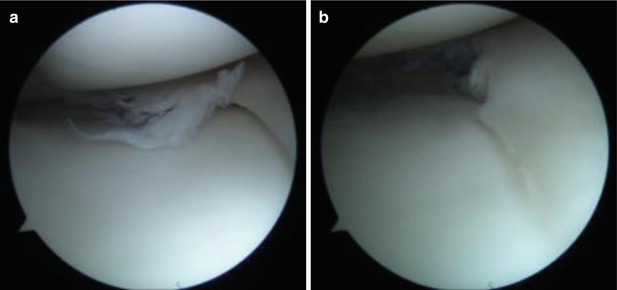

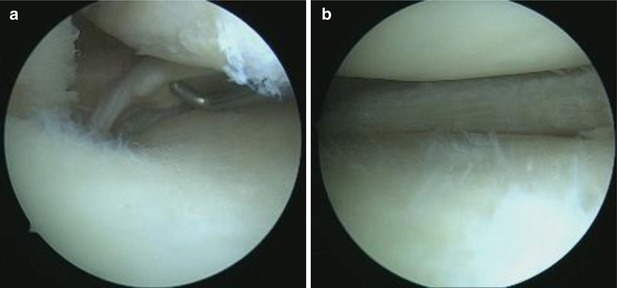

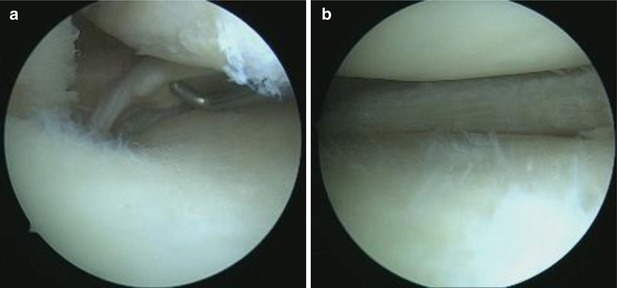

Fig. 2.3

“Parrot-beak” medial meniscal rupture

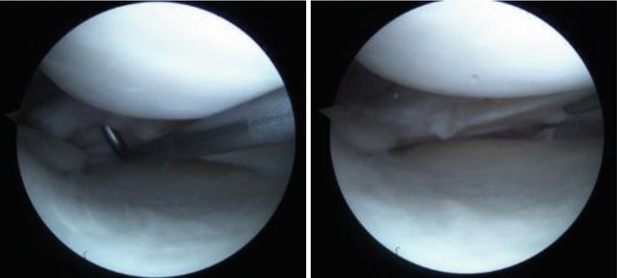

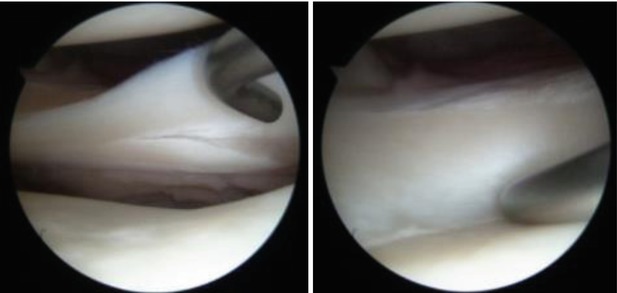

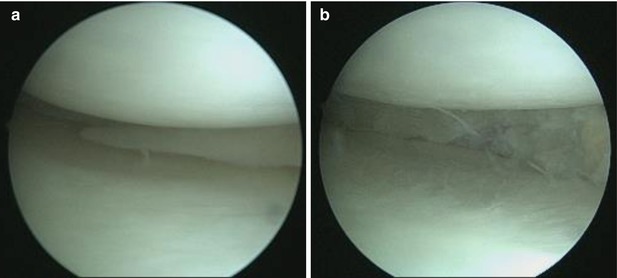

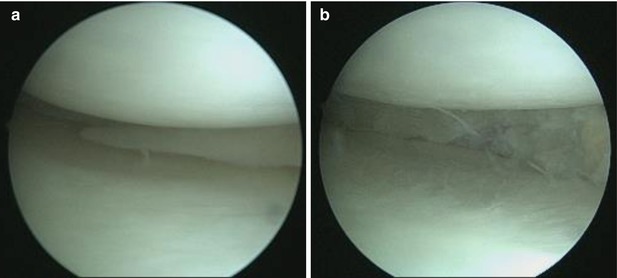

Fig. 2.4

Posterior horn rupture of the medial meniscus associated with an Outerbridge II condral pathology. The lesion extends towards the capsular portion and the insertion of the posterior part of the meniscus

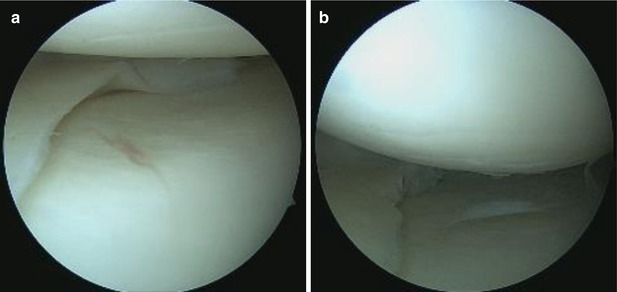

Fig. 2.5

“Bucket-handle” lesion of the medial meniscus associated with an intercondylar dislocation of the torn piece

Fig. 2.6

Rupture of the medial meniscus (a), which underwent partial meniscectomy (b)

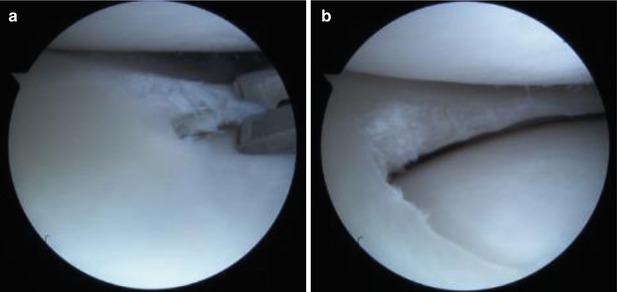

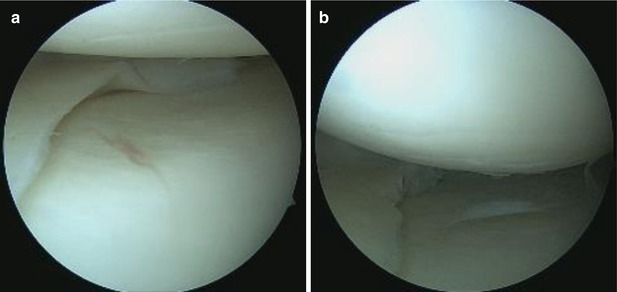

Fig. 2.7

Degenerative lesion located on the posterior portion of the medial meniscus, before (a) and after (b) the partial meniscectomy

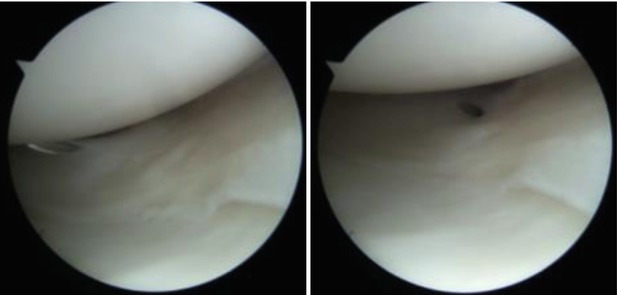

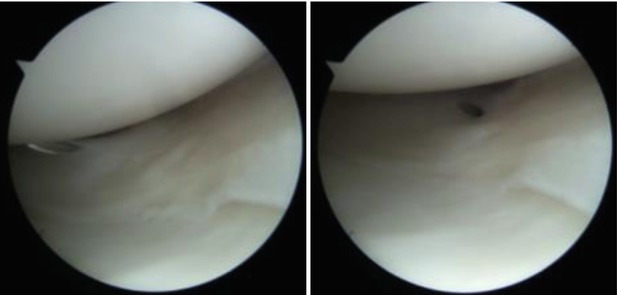

Fig. 2.8

Stable longitudinal tear of the lateral meniscus

Fig. 2.9

Complete horizontal tear of the external meniscus

Fig. 2.10

A complex degenerative tear of the external meniscus. Secondary condral pathology Outerbridge II. The popliteal tendon can be seen in the posterior aspect

2.1.4 Imaging

Magnetic resonance Imaging is considered the “gold standard” and is the most frequently used imaging technique in the diagnosis of internal knee injuries. Even though it is a highly sensitive investigation when it comes to finding meniscal injuries, it may often yield false-positive or false-negative results. Thus, it is very important to be able to correlate the imagistic findings with the symptoms of the patient. In a study conducted by Crues et al. in the late 80’s, it was showed that at surgery, 89 % of the patients diagnosed on MRI with grade 1 and 2 ruptures, were found to be normal during arthroscopy.

Meniscal tears are defined as an intrasubstance hyperdensity that reaches the surface of the meniscus [8]. The most often depicted meniscal tear is located in the posterior portion of the medial meniscus. This is due to the fact that it is the thickest meniscal segment, and hyperintensity intrasubstance can be observed with ease.

The probability that a tear is present increases if the specific signal changes are seen in more consecutive slices and in both sagittal and coronal planes. The sensitivity decreases to 55 and 30 % if the signal changes are only seen on one slice for the medial meniscus and lateral meniscus respectively [8]. Complete meniscal tears reach both the superior and inferior surfaces, while the partial tears only affect one of the two [9].

Von Engelhardt et al. studied the correlation between a 3-T MRI and arthroscopy meniscal tear diagnosis. They revealed that the MRI showed an increased accuracy in diagnosing medial meniscal tears (complex and horizontal tears were prevalent) than lateral meniscal tears. Regarding the grade III medial meniscal tears, the MRI had a 86 % sensitivity and a 100 % specificity. These two values decreased to 79 and 95 % respectively for the lateral meniscus. Grade II tears had a rate of 24 % missed diagnosis, while grade I lesions were not associated with an arthroscopic tear [10]. This changes dramatically regarding grade 3 lesions which showed a rate of confirmation during surgery of 91.3 % [11]. In 2009 Khanna et al. stated that false MRI results can be avoided by having a better understanding of several misconceptions. Thus, by being able to recognize the “magic angle” phenomenon, knowing the physics of an MRI, the anatomy and the pathophysiology of certain diseases, many of these errors can be avoided [12].

MRI-artrography has proven to be an efficient way of diagnosing meniscal tears, proving high rates of sensitivity and specificity. Mathieu et al. have shown that MR-artrography exceeds MRI regarding these two aspects, reaching values of 100 % sensitivity and 89.6 % specificity, while the MRI’s rates were 92.3 and 82.8 % respectively. The study was carried out on 21 patients (15 males) with a mean age of 35.7 years. MR-artrography is indicated in the detection of foreign bodies within the knee joint, detection on secondary tears on operated menisci and assessment before chondral lesion repairs. The lack of lesion depth resolution though, advantages the classic MRI [13].

The ultrasonography is inexpensive and easily accessible. It has been recently put to use in the case of acute internal knee injury. The advantages it has over classic MRI are the cost efficiency, portability of the equipment and duration of assessment. Compared to the MRI, the diagnosis made with ultrasonography has proven to have higher specificity rates (84.2 %/66.7 %), higher correct classification rates (89.5 %/81.5 %) and similar sensitivity rates (91.2 %/91.7 %) [14].

Typically, the patient’s lifestyle, size, localization and shape of the tear indicate a certain type of treatment. Conservative treatment is usually an indication in small tears that can be found in patients with a rather sedentary lifestyle that does not involve sport activities, resulting in little to no symptoms. Rathleff et al. conducted a clinical trial that evaluated conservative treatment in patients with MRI-confirmed meniscal lesions. Their success rate for this type of treatment was 58 %, and it was determined using the KOOS and Lysholm score [15]. Large and complex tears require arthroscopic surgery, be it by resection or meniscal suture. Resection is usually an indication when tears involve the free edge of the meniscus which has less chance of healing (due to the lack of vascularization) than the tears in the more vascularized area of the meniscus (near the tibial insertion point).

2.1.5 Incomplete Meniscal Tears During ACL Reconstruction

One of the topics that are still debated is defining the management of incomplete meniscal tears found during anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions. One of the first studies to approach this subject found that stable vertical longitudinal tears, in the periphery of the menisci, have good healing whereas radial tears, in the avascular third of the meniscus, do not have the same favorable healing potential. They recommend for stable longitudinal tears to be left in situ but cannot find a solution for the vertical lesions [16]. Further research has also found that peripheral meniscal lesions associated with surgery for chronic anterior instability do not always require suture if they are limited to the posterior segment [17].

The debate has then focused on laterality and length of the lesions. Shelbourne et al. have shown favorable long term follow-up for lateral meniscal tears left in situ or stimulated by abrasion or trephination that are posterior horn, stable radial flap, or peripheral/posterior third tears which extend less than 10 mm in front of the popliteus tendon [18]. In a previous study, the same authors also found that posterior horn avulsions, vertical tears posterior to the popliteus tendon and other stable tears at the time of index anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction can be left in situ without becoming clinically symptomatic [19].

With regard to the medial meniscus, Shelbourne et al. observed most traumatic stable peripheral vertical medial meniscus tears treated with abrasion/ trephination to be asymptomatic without stabilization [20]. Other studies also found limited stable medial lesions and most lateral tears to have good outcomes when left untreated during ACL reconstruction [21–23]. Furthermore, meniscal rasping is feasible for repairing longitudinal tears in the avascular region of the meniscus, but the healing potential is influenced by the distance to the capsule, length and stability of the tear [24].

Detection of incomplete or subtle meniscal tears is highly dependent on the quality of the MRI as well as the examiners proficiency. A correlation between arthroscopic findings of incomplete meniscal tears and preoperative MRIs performed in different locations found the initial radiologist interpretation failed to identify most medial and all lateral incomplete lesions of either meniscus when the acquisition was performed on a 0.2 T open MRI. Even with the 1.5 T MRI the findings were missed in 47 % of the cases for the lateral meniscus [25]. There were considerable more missed lesions when compared to the literature [26] with all machines but we can conclude that 0.2 T MRIs cannot be used to successfully identify incomplete meniscal tears in the setting of anterior cruciate ligament rupture.

Pujol et al. performed a literature review concerning the healing results of meniscal tears left in situ during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and recommend fixation for medial meniscus tears [27]. These findings are supported by other authors that found meniscal repairs at the time of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction had a lower failure rate than isolated repairs and better long-term outcomes than partial meniscectomy [28]. One explanation might be that longitudinal tears of the medial meniscus in an ACL-deficient knee alter kinematics; particularly the anterior-posterior tibial translation comparable to a partial meniscectomy and that stability can be improved by repair [29].

A more recent review performed by Noyes et al. found that meniscectomy is performed two to three times more frequently than meniscus repair during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction [30]. This raises concern since meniscectomy significantly alters long term outcomes and favors arthritic changes, especially in the lateral compartment [31]. To a certain degree, this can be attenuated by the fact that lateral meniscus tears are better tolerated and can be excised more parsimoniously hoping they will continue to provide support [32].

Vermesan et al. concluded that incomplete medial meniscal tears left in situ at the time of anterior cruciate ligament can yield favorable outcomes as long as decisions are carefully weighed with regard to length of the lesion. Also, at least in this perspective, anatomic single bundle has proved a sufficient stabilizer for anterior translation of the tibia [33].

2.2 Meniscectomy

Meniscal pathology remains a commonly encountered clinical entity for the practicing orthopedic surgeon. In Clayton and Court-Brown’s recent prospective study of musculoskeletal injuries, meniscal injury to the knee was the most common, occurring at a rate of 23.8/100,000 per year. According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, the incidence in the United States is 61/100,000 [34].

The first description of a meniscectomy was provided by Broadhurst, in 1866 in London. Annandale was the first to describe meniscal repair in 1885. Despite the reports of King and Fairbanks, who described the harmful effects of total meniscectomy and the secondary radiographic changes, until the seventies, menisci were considered as functionless evolutionary remnants of leg muscle that could be excised without further relevant consequences for the knee joint [35]. In 1948, Ghormley recommended total excision of any torn meniscus, stating that partial meniscectomy carried a higher risk of joint surface damage [36]. In the fifties, Trillat and Dejour highlighted the role of the meniscal rim. Trillat described intramural medial meniscectomy through a short anteromedial arthrotomy, preserving the medial collateral ligament and the meniscal rim [37]. However, the first arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is generally attributed to Watanabe (disciple of Takagi) in 1962. He designed the first practical arthroscope: the Watanabe number-21 arthroscope, which was produced in series and allowed effective intraarticular exploration [38].

Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is the most common orthopedic procedure performed in the United States. The aim of the procedure is to relieve symptoms attributed to a meniscal tear by removing torn meniscal fragments and trimming the meniscus back to a stable rim. Most treated meniscal tears are associated with degenerative knee disease, which can range from mild chondral changes not visible on a radiograph to established knee osteoarthritis. Objectives of meniscus surgery are return to previous activity level, relieve symptoms associated with tears, not increase risk of late osteoarthritis, not add further problems [39]. Approximately 700,000 arthroscopic partial meniscectomies are performed annually in the United States alone [40]. Metcalf et al. concluded that partial meniscectomy is better than total meniscectomy because less operative time, enhanced recovery rate, improved long term stability. They also concluded than arthroscopic is better than open meniscectomy with less operative time and quicker recovery post-op [41].

Arthroscopic medial meniscectomy is performed with the patient under spinal or general anesthesia. A tourniquet is applied to the thigh and it can be or not inflated [42]. A thigh holder or lateral post is used to allow for controlled varus and valgus stress. The leg is positioned in a leg holder, which allows valgus stress to be exerted across the joint to open up the medial compartment for adequate visualization [43]. The patient may be positioned so that the leg can be draped off the side of the bed if using a lateral post or the end of the bed can be lowered when using a thigh holder [44].

The antero-medial and antero-lateral portals are sufficient to achieve the majority of medial meniscectomies. First, the antero-lateral portal will be performed to introduce the arthro-trocar sleeve and the arthroscope [45]. The anterolateral portal is the primary viewing portal for knee arthroscopy. With the knee flexed to 90°, the inferior pole of the patella, the lateral border of the patella and the lateral joint line are palpated [46]. An incision is made with a no. 11 blade approximately 1 cm above the joint line and in line with the lateral border of the patella. A vertical incision angled toward the intercondylar notch is used unless a horizontal portal is preferred. In either case, great care is taken to protect the meniscus and intraarticular structures [47]. The trocar sleeve will be introduced after cutting the skin and the patella with a scalpel and then it will be directed to the intercondylar notch, the knee being flexed at 30° or 45°. Then, the arthroscope will be directed towards the femoral-patellar joint, with the knee in extension, to start the exploration [48].

The anteromedial portal is created with the knee at 30° of flexion. The 30° scope needs to be rotated to obtain an unobstructed view of the anterior aspect of the medial meniscus and anterior capsule [49]. The anteromedial portal will be performed by trans-illumination in the dihedral antero-medial angle above the anterior segment of the medial meniscus. Then the probe will be introduced to palpate both menisci on their two sides by lifting them and the two cruciate ligaments. The anteromedial portal will be more or less high and medial according to the lesion localization [50].

The lateral meniscus shows anatomic particularities different from those of the medial meniscus. The accessibility of the anterior segment is often difficult. The standard arthroscopic meniscectomy portals are used and in case an accessory portal may be use, through the patelar tendon. For arthroscopic lateral meniscectomy, the lateral skin incision should be superior to the joint line and for arthroscopic lateral meniscectomy, the lateral skin incision should be superior to the joint line [51].

Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy is a 10–20 min procedure where torn or mobile areas are removed and edges contoured to prevent further tears. It has the advantage that immediate partial weight bearing is allowed. Partial meniscectomy is indicated in complex tears, flap tears, radial tears, rupture in the white-white zone, degenerative tears and degenerative horizontal cleavage [52].

Metcalf described basic principles to adhere to when performing partial meniscectomy procedure. This includes: remove all mobile fragments, do not leave sudden changes in rim contour, do not try to obtain a perfectly smooth rim as some remodeling may occur, use the probe often to reevaluate the tear, protect the meniscus-capsular junction to avoid the loss of hoop stresses, use both manual and motorized instruments to maximize efficiency when uncertain if an area should be resected, we should opt for leaving more meniscus intact rather than compromising biomechanical properties [53].

Meniscus resection – basic steps: instrumental meniscal resection (punch), removal of residual tissue (avoiding thus irritation and hidarthrosis, shaving, coagulation of bleeding vessels. In a “bucket handle tear” first reduction of the displaced meniscus then identification/resection of the posterior basis, identification/resection oft the anterior bases, removal of the meniscal tissue, smoothening of the structure [54]. In a meniscal flap the steps are reduction of the flap, resection, removal of the flap, smoothening. In degenerative meniscla lesion resection is performed along with removal of lost fragments and smoothening. Adequate instruments are use to perform the procedure such as punches, scizors, hook, shaver, radiofrequency, cautery [33].

The arthroscopy ends up with a thorough cleaning of the knee. Any meniscus fragments must be removed without leaving any remnants in the portals which will become a source of chronic pain. The closure of the portals is carried out by several ways: non resorbable sutures, staples or even adhesive tape [55].

In a longer-term study, Burks and colleagues reported 88 % good and excellent results after 15 years follow-up. They also reported that results were not significantly different for medial versus lateral tears. Patients with valgus as opposed to varus alignment had better results after partial medial meniscectomy. Radiographic examinations demonstrated a 0.24 % mean decline in osteoarthritis grade. Of note, their study population consisted of low-demand patients [56].

Full weightbearing ambulation is possible immediately after surgery. In the context of degenerative lesions, sports activity will depend above all on the degree of coexistent cartilage lesions. Physical therapy can be used for residual pain [57]. Patients are allowed to return to full athletic activities when their quadriceps muscle tone returns and they have full painless range of motion. This varies but usually averages 4–6 weeks postoperatively and slightly longer in the setting of degenerative changes [58].

Vermesan et al. compared arthroscopic debridement with intra-articular steroids in degenerative medial meniscal tears. They concluded that arthroscopic debridement has marginal better outcomes. They identified several negative prognostic factors such as obesity, meniscal extrusion and bone marrow edema [33].

Complications are rarely seen. The risk of infection is about 0.1 %. Hydrarthrosis is more common after a lateral than a medial meniscectomy. This can be explained by the congruence of the lateral tibial plateau, which is more convex than the medial one. This incongruence increases the mechanical conflict. Contrary to meniscal repair techniques, arthroscopic meniscectomy is very rarely fraught with vascular or nervous complications [59].

Small reported on the complications of 21 experienced arthroscopists over a 19-month period. The complication rates for arthroscopic partial medial and lateral meniscectomies were 1.78 and 1.48 %, respectively. Partial meniscectomy can be complicated by instrument failure, knee ligament injury, neurovascular injury, iatrogenic damage to articular cartilage through aggressive instrumental manipulation, also can generate further damage to cartilage and can lead to arthritis. Inadequate resection with persistence of meniscal lesion can happen by lack of arthroscopic knowledge, inexperienced surgeon or re-arthroscopy [60].

Knee ligament injury during partial meniscectomy usually involves the medial collateral ligament. This infrequent injury may occur when excessive valgus force is placed on the knee in an attempt to gain better access to the medial compartment [61]. This can make a prolonged recovery but it always heal. Persistent pain after partial meniscectomy may occur because of incomplete resection of the tear or from coexistent knee pathology. When resecting a tear, in an attempt to preserve the maximal amount of menisci, it is possible that torn remnants may be left behind [62] (Figs. 2.11, 2.12, 2.13, 2.14, 2.15, 2.16, 2.17 and 2.18).

Fig. 2.11

Tear of the medial meniscus’ posterior horn. Before (a) and after (b) the punch meniscectomy

Fig. 2.12

Radial rupture of the medial meniscus before (a) and after (b) punch meniscectomy

Fig. 2.13

Complex lesion of the medial meniscus – punch meniscectomy (a). The post-meniscectomy appearance reveals the lesion extending near the capsular portion of the meniscus (b)

Fig. 2.14

A small tear of the lateral meniscus body showed to us by the help of a probe, before (a) and after (b) smoothening of the articular border was performed

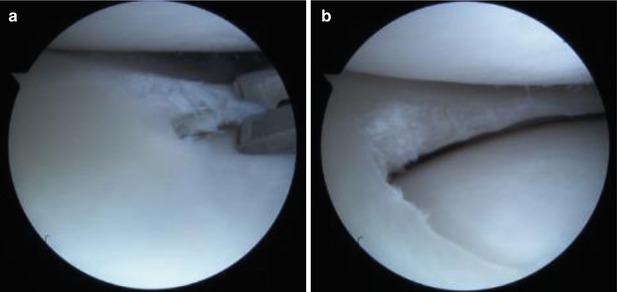

Fig. 2.15

Posterior horn avulsion tear of the medial meniscus and chondral damage (a). This particular type is frequently missed on preoperative MRI examination. Punch meniscectomy is performed and the final result can be observed in the second picture (b)

Fig. 2.16

Longitudinal tear of the lateral meniscus posterior horn and body. Subsequent early cartilage damage can be observed (a). Meniscus aspect after the meniscectomy has been performed (b)

Fig. 2.17

Old tear located on the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus. Cartilage damage can also be observed (a). The torn piece is removed and the edges of the meniscus are evened out (b)

Fig. 2.18

A “bucket-handle” lesion of the external meniscus before (a) and after the intercondylar luxation reduction (b). Pictures taken during the meniscectomy (c), and after the torn piece was removed (d)

2.3 Meniscal Preservation

2.3.1 Meniscal Repair

In the eighties, biomechanical studies stated the importance of menisci to load transfer. Kurosawa et al. showed that total meniscectomy reduced the total contact area by a third to a half in a fully extended knee [63]. Menisci transmit up to 50 % of weightbearing forces in extension and about 85 % in flexion. In vitro trials reported about 70 and 50 % of load transmission through the corresponding menisci in the lateral and medial compartment, respectively. This combined knowledge stressed the relevance of meniscal preservation, and partial meniscectomy gained ground over total excision [64].

The development of arthroscopic surgical instruments and techniques facilitated a movement toward meniscus preserving surgery. Rather than resection of the entire meniscus, partial meniscectomy became a mainstay of treatment for symptomatic tears. Short-term results of partial meniscectomy are excellent. Jarequito and associates reported 90 % good and excellent outcomes at 2-years follow-up, with 85 % of patients returning to their desired activity level. At 8 years, though, these results had declined to only 62 % good or excellent outcomes, and only 48 % of patients maintained their desired activity level [65].

Due to the long-term complications that meniscectomy induces, such as joint space narrowing followed by degenerative changes [64, 65], more and more arthroscopists have initiated the trend of meniscal repair. Annandale [66] was the first to perform and report meniscal repairs, but his idea was not received with open arms and it was very soon put aside. With the advances made in arthroscopy, the meniscal repair techniques have evolved and are now used worldwide. The first arthroscopic meniscal repair was performed in 1969 by Ikeuchi [67]. With the development of new implants, all of the repair techniques including inside-out, outside-in and all-inside have become less demanding and now cause less postoperative complications.

2.3.1.1 Basic Principles

In order to easily asses the healing potential of a meniscal tear and to be able to treat it correctly, these injuries were classified according to their location on the meniscus and the grade of vascularization it has. Thus, Arnoczky and Warren have named zone 0 the peripheral meniscosynovial junction, zone 1 the red-red zone, zone 2 the red-white zone and zone 3 the white-white zone [66]. Depending on the zone, the rupture is less likely to heal [68], or not, after a meniscal repair. A tear in the red-red zone is likely to heal, whereas a tear in the white-white zone has little to none healing chances.

Once the type of meniscal tear has been assessed, before doing the repair, the surgeon has to perform arthroscopic debridement if necessary. Pujol et al. proposed that using a posterior portal may improve the precision of the debridement [69]. Bucked-handle tears have to be reduced back to their anatomic position, and needling can be performed for meniscal healing stimulation (Fig. 2.19).

Fig. 2.19

Incomplete rupture of the meniscus located in the red-red zone. Needling is performed

2.3.1.2 Arthroscopically Assisted Repairs

The development of the less invasive techniques aimed at reducing the disadvantages that came along with the open repair. It was meant to allow for a faster recovery, lower the rate of morbidity and grant a good option when dealing with lesions found in the red-white zone. The inside-out and outside-in can be used as complementary repairs in different meniscal tears or long longitudinal tears. Posterior and middle segment ruptures benefit from the inside-out repair, while anterior horn sutures benefit from the outside-in technique better.

Outside-in repairs were first performed by Warren in 1985 [70]. A variation to this technique has been described. A cannulated needle is passed through the tear from the outside, into the knee joint. When the tip has reached the surface of the meniscus, the suture (2 nonabsorbable) is passed through. A second needle is passed on the other side of the rupture and a thin looped nonabsorbable monofilament (2/0) suture is passed. With the help of the probe and an arthroscopic grasp the suture is passed through the loop under arthroscopic visualization. The loop, the suture and the needle are all pulled back out of the joint and tied to one another on the exterior portion of the capsule through a small incision (Figs. 2.20 and 2.21).

Fig. 2.20

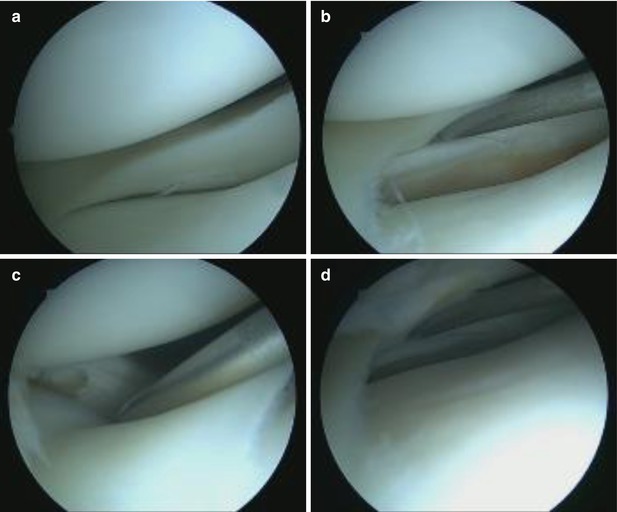

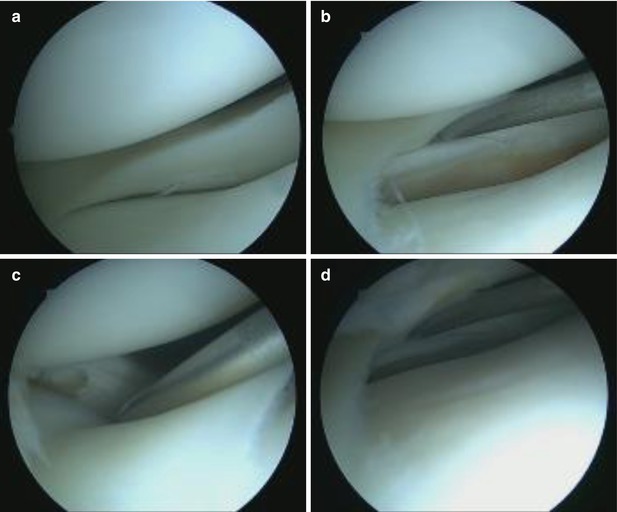

Arthroscopic view of an external meniscal longitudinal rupture (a–d), indicated with the probe

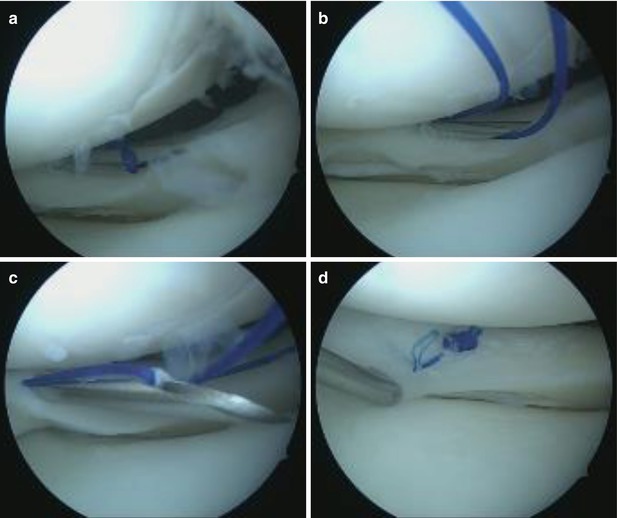

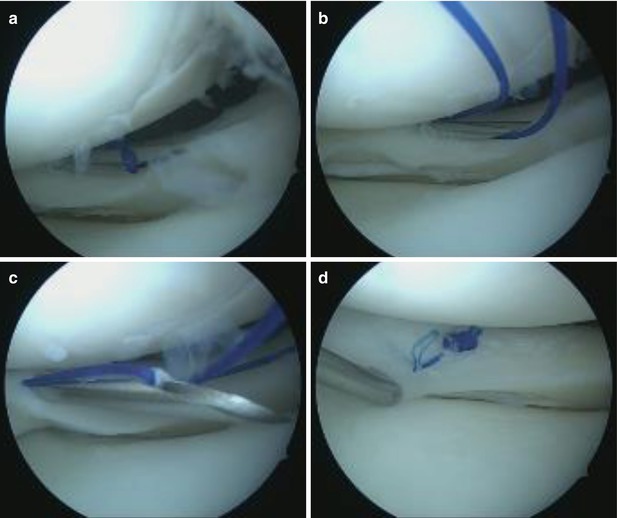

Fig. 2.21

Meniscal suture of the same case above, performed through an inside out technique (a–c). The final aspect of the tied knot can be viewed in the last picture (d)

The inside-out technique. Most systems mainly consist of long curved single or double-barrel canulas. The stitches can be horizontal or vertical and they usually consist of absorbable or nonabsorbable 2-0 sutures. The sutures are then retrieved through a posterior extraarticular incision (medially or laterally), with the knots being tied outside the joint, over the knee capsule. The disadvantages of this technique are the neurovascular complications that may arise. The posteromedial or posterolateral incision must be positioned carefully as to not harm the saphenous vein and/or nerve and the peroneal nerve respectively.

2.3.1.3 Implant Assisted Repairs

The need for managing meniscal repairs in an all-inside fashion, without the use of any other accessory incisions, has led to the production of various implants that were deemed suited for this task. They are made out of bioabsorbable materials, mostly composed of rigid poly-l-lactic acid (PLLA), and come in many shapes such as screws, anchors, staples, etc.

This type of technique can be performed easily and very fast. It also has a low risk of neurovascular injury and it requires no accessory incision. Some disadvantages have been proven in time. Their strength is lower when compared to vertical sutures [71, 72], and they have a risk of presenting loose bodies, developing synovitis and meniscal cysts, as well as cartilage abrasion [73–76].

2.3.1.4 All-Inside Meniscal Repairs

These types of techniques are the latest developed treatments in the field of meniscal sutures. All of them are achieved with specially designed devices that allow for easy and secure repair using only arthroscopic portals. The principle that they are designed around is positioning one or two anchors behind the capsule while a compressing suture holds the torn parts of the meniscus together. This suture is locked in place with a sliding knot.

2.3.1.5 FasT-Fix

Is a successful device manufactured by Smith and Nephew. It consists of two 5 mm polymer anchors with a pre-tied self-sliding knot made up from 2 to 0 non-absorbable ultra high molecular weight polyethylene suture. This system is integrated alongside in an ergonomic “screwdriver-like” handle with anchor-release buttons, a knot-pusher, an adjustable length limiter and a delivery needle which can be curve-shaped or straight. The device allows placing vertical mattress sutures on the femoral as well as on the tibial surface (using the inversed curve-shaped needle) of the meniscus.

It is recommended that we use the anterolateral portal for repairing lateral meniscal tear, and middle-zone medial meniscal tears and the anteromedial portal for the other medial meniscal tears. A proper measurement of the needle depth limit is very important as it reduces neurovascular lesions to the minimum and it allows for a correct positioning of the anchors. A slotted cannula can be used for knee guidance inside the knee in order to avoid unwanted chondral damage and support the needle during the positioning process.

Vertical mattress sutures are made by placing the first implant (anchor) in the capsular side of the meniscus, pulling the suture back out of the meniscus and then re-inserting it in the inner meniscal fragment. The suture is then tensioned and the knot is slid into place and then cut. Several sutures can be placed at a recommended gap of 5 mm from one another. For horizontal mattress sutures the same steps apply, but the first anchor is placed in the posterior side of the meniscus and the second one is deployed anterior to the rupture (Figs. 2.22 and 2.23).