CHAPTER 5 The medical and social history

Introduction

Purpose of the medical and social history

An inadequate history of the patient’s health status may have the following consequences:

1. The patient is placed at risk.

With an inadequate knowledge of the patient’s medical history, inappropriate or unsafe treatment may be provided. The actual risk of causing a bacteraemia in a patient with a prosthetic joint (which could infect and then loosen the joint) by performing nail surgery remains unquantified but a theoretical risk certainly exists. Bacteraemia in patients with a history of endocarditis or rheumatic valvular disease may lead to bacterial growth on the previously damaged heart valves or endocardium. Inadequate knowledge of the patient’s existing medication could lead to adverse inter-drug reactions with newly prescribed treatment. If drugs are prescribed (or omitted) in the absence of a detailed medical history, an existing condition may be exacerbated. For example, aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may precipitate asthma attacks.

2. The practitioner is placed at risk.

4. An increased risk of clinical emergencies.

All these factors have implications for cost and litigation.

Format of the medical and social history enquiry

A systematic approach to history taking will ensure that the practitioner covers all relevant areas in the enquiry process. The medical history and systems enquiry presented is based on the hospital assessment or clinical clerking system. Findings recorded with this system (Box 5.1) will determine the need for further clinical or laboratory investigation and indicate the patient’s suitability for a range of treatments.

Box 5.1 The medical history and systems enquiry

Part 3. Personal social history

Part 4. The systems enquiry (CRAGCEL)

Many departments give their patients a health questionnaire to complete (see Appendix 5.1). This can be sent to the patient before the initial visit or, more commonly, before they see the practitioner again. The use of questionnaires gives patients time to consider their answers and reduces the time spent in taking a medical history during the consultation.

Medical history

Current health status

Before history taking begins, the practitioner will gain some impressions about the patient’s current health status from simple observation. Patients should be observed from the moment they enter the consulting room. Diseases of nerves, muscle, bone and joints may be manifested by a patient’s gait or posture. For example, upper and lower motor neurone lesions may cause an ataxic gait, in which coordination and balance are impaired. Patients with acute foot or leg pain will walk with a limp as they try to ‘guard’ the injured part. Patients with chronic foot disorders may shuffle rather than stride because a propulsive gait could cause more pain. Gait disorders in children are best visualised as the child walks into the room to meet the practitioner; children often become self-conscious when asked to walk on demand.

The following questions will reveal important information about the patient’s general health:

• Are you under the doctor or consultant for any treatment currently?

• Do you feel tired during the day?

Past and current medication

Large doses or prolonged use of certain medications can be associated with significant adverse drug reactions with relevance to the lower limb. Most drugs produce several effects, but the prescriber usually wants a patient to experience only one (or a few) of them; the other effects may be regarded as undesired. Although most people use the term ‘side effect’, the term ‘adverse drug reaction’ is more appropriate for effects that are undesired, unpleasant, noxious or potentially harmful. For example, prednisolone, commonly used in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, can reduce skin thickness and impair wound healing. Bendroflumethiazide, a useful diuretic for the treatment of cardiac failure or hypertension, can cause hyperuricaemia, which may result in gout-like symptoms. Warfarin, an oral anticoagulant used for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, increases clotting time and has obvious implications if surgical treatment is planned. Other examples of adverse drug reactions are listed in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Adverse effects of drugs affecting the lower limb

| Drug | Therapeutic use | Side effects |

|---|---|---|

| Beta-blockers | Hypertension | Coldness of extremities |

| Calcium channel blockers | Hypertension | Ankle oedema |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors | Hypertension | Muscle cramps |

| Propanolol | Hypertension | Paraesthesia |

| Furosemide | Hypertension | Bullous eruptions |

| Salbutamol | Asthma | Peripheral vasodilatation |

| The contraceptive pill | Contraception | Increased risk of deep vein thrombosis |

| Colchicine | Gout | Sensorimotor neuropathy |

| Indometacin | Arthritis | Sensorimotor neuropathy |

| Corticosteroids | Inflammation | Osteoporosis, skin atrophy |

| Aspirin | Pain management | Purpura |

| Metronidazole | Anaerobic infections | Sensorimotor neuropathy |

| 4-quinolones | Infection | Damage to epiphyseal cartilage |

| Chloramphenicol | Infection | Peripheral neuritis |

| Nalidixic acid | Infection | Bullous eruptions |

Patients should also be asked if they are currently taking or have taken in the past any tablets or medicine or used any ointments or creams which they have purchased from a chemist. Self-prescribed medication is of interest to the practitioner not least because the quantities used may be quite variable, with the possibility of chronic overdosing. For example, repeatedly exceeding the recommended daily dosage of vitamins A and D supplements may lead to ectopic calcification in tendon, muscle and periarticular tissue.

Of particular concern to the podiatric practitioner is the potential for overdosage of local anaesthetics, which can lead to convulsions as a result of central nervous system depression. This may be followed by a profound drop in blood pressure and life-threatening cardiovascular depression. In such circumstances oxygen must be administered to support the patient. The risk of such a clinical emergency can be minimised by adhering to the maximum safe dose for the various local anaesthetic agents and always having oxygen available.

• have Cut down on drinking – have tried repeatedly without success

• are Annoyed by criticism about drinking habits

• have Guilty feelings about drinking

Past medical history

• Have you been off work due to illness for more than 1 week in the past 6 months?

• Have you ever been admitted to hospital?

• Have you ever had an operation?

• Have you ever been under the care of a consultant or a hospital specialist?

Hospitalisations for operations or injuries should be recorded and any complications noted (Case history 5.1). In females, a particularly common procedure is hysterectomy, which has implications for the lower limb in that the effect on hormone balance can lead to premature osteoporosis. This may manifest clinically as vertebral collapse, leading to spinal deformity and possible neural compression. Injuries may often appear to be unrelated to the patient’s presenting complaint but it must be remembered that the lower limb functions as one unit and if one component of the unit is damaged, it can lead to compensations elsewhere in the lower limb. If a patient is still under the care of a hospital consultant it is prudent to inform the consultant before any treatment is given that may affect other body systems.

Family history

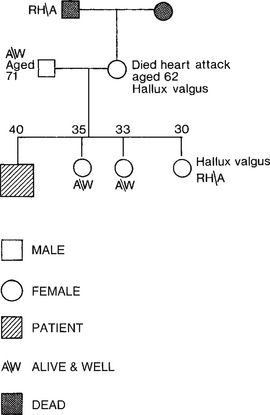

A pedigree chart may be used to record details of major illnesses and lower limb problems of the immediate family (Fig. 5.1). Conventions exist regarding the symbols used in the charts. The author’s favourite quote from a patient was that ‘they don’t make old bones in my family!’

Personal social history

Occupation

A patient’s occupation may be a contributory cause of the lower limb problem and may influence the treatment that can be given (Case history 5.2). Some patients may experience particular difficulties in taking time from work to attend for treatment. The nature of the work should be determined (what they actually do) and special footwear requirements should be noted. The types of surface that the patient stands and walks on during the day can be exciting factors. Bare concrete floors will exacerbate chilblains, whereas patients whose occupation involves standing on ladders will often suffer from chronic medial longitudinal arch pain.

Sports and hobbies

Active sportsmen and women may make the association between their sport and a lower limb problem, but those who participate in occasional sporting activities and hobbies may not. Patients who participate in infrequent sporting activities may not think of informing the practitioner of these activities. However, these patients are often more prone to injury because they are often not as fit and do not follow appropriate warm-up and warm-down regimens. These patients are more likely to develop hamstring or calf muscle injury due to poor flexibility – the so-called weekend warrior. Details of any sporting hobby should therefore be sought from the patient. The assessment of the patient with a sports injury is considered in detail in Chapter 15.

Foreign travel

Details of foreign travel should be recorded in case the patient has acquired an infection while abroad. In particular, recent travel to tropical countries and details of any foot injuries sustained while walking barefoot should be recorded (Case history 5.3). Ask if the visit was urban or rural and whether they had any specific vaccinations.

The systems enquiry

All the body systems are worked through in a set order, which can be remembered using the acronym ‘CRAGCEL’ (see Box 5.1). The systems enquiry involves asking questions that will seem, to the patient, to be quite unrelated to the lower limb problem. It is important that patients are advised before the enquiry begins that the purpose of the questions is to ensure that there are no general health problems that may be causing the lower limb condition or that may influence the type of treatment considered.

Cardiovascular system

Congestive heart failure (CHF) results from the inability of the heart to sufficiently supply oxygenated blood to the tissues. Causes include valvular heart disease, myocardial disease and hypertension (Case history 5.4). Arrhythmias may present as bradycardia (slow heartbeat) or tachycardia (fast heartbeat) with varying degrees of irregularity. Certain rhythms such as ventricular tachycardia predispose to cardiac arrest.

The most important cardiovascular symptom to elicit is chest pain (Table 5.2) because of the range of pathologies responsible for its occurrence. The differential diagnosis includes MI, angina pectoris, pneumonia, pericarditis and oesophageal reflux. The pain of angina is tight and pressure-like, precipitated by exercise and relieved by rest, and usually lasts for only a few minutes. The pain in an MI is similar in nature but is much more intense, lasting from 30 minutes to 3 hours.

Table 5.2 Common causes of chest pain

| Cause | Common symptoms | Common signs |

|---|---|---|

| MI | Central, crushing pain that radiates into the arms and jaw. Nausea, vomiting, anxiety and sweating | Pain, sweating, tachycardia |

| Angina | Heavy central chest pain precipitated by activity and stress and relieved by rest | May be absent |

| Pulmonary embolus | Central or pleuritic chest pain. Sudden onset shortness of breath | Tachycardia, tachypnoea, hypotension |

| Pleurisy | Sharp, localised stabbing pain exacerbated by breathing, coughing and movement | Fever |

| Dyspepsia | Central epigastric sharp or burning pain which can radiate to the back | Epigastric tenderness |

| Musculoskeletal | Localised pain exacerbated by breathing, coughing and movement | Localised tenderness |

Syncope (fainting) is a transient loss of consciousness. Cardiac disease such as arrhythmias and aortic stenosis can cause syncope by decreasing the cerebral blood supply. Other less-specific systemic cardiac symptoms include fatigue and decreased exertional tolerance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree