Chapter 4 The measurement of patient-reported outcome in the rheumatic diseases

KEY POINTS

The measurement and communication of disease burden and the consequence of healthcare are essential components of healthcare. Patients have an important contribution to make to this process.

The measurement and communication of disease burden and the consequence of healthcare are essential components of healthcare. Patients have an important contribution to make to this process. Well-developed patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) can provide a reliable, valid and clinically relevant resource for including the patient perspective in healthcare

Well-developed patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) can provide a reliable, valid and clinically relevant resource for including the patient perspective in healthcare The effective incorporation of PROMs into routine practice requires training in the use and interpretation of PROMs and ongoing support to ensure the appropriate use of PROMs-related data. Further rigorous evaluation of the contribution of PROMs to routine practice is required

The effective incorporation of PROMs into routine practice requires training in the use and interpretation of PROMs and ongoing support to ensure the appropriate use of PROMs-related data. Further rigorous evaluation of the contribution of PROMs to routine practice is required Advances in technology, such as electronic data capture, may enhance the feasibility of PROM application, whilst the timely provision of scores may enhance the utility to routine practice. Demonstrating the cost effectiveness of incorporating PROMs into routine practice is essential to good practice and to attracting appropriate resources to support data collection

Advances in technology, such as electronic data capture, may enhance the feasibility of PROM application, whilst the timely provision of scores may enhance the utility to routine practice. Demonstrating the cost effectiveness of incorporating PROMs into routine practice is essential to good practice and to attracting appropriate resources to support data collectionINTRODUCTION

Most modern healthcare systems embrace patient-centred care, entailing care that is responsive to the needs, preferences and values of the individual (Hibbard 2003). However, the experience of health and illness, and outcomes of healthcare desired by patients are multifaceted and often uniquely individual (Quest et al 2003, Ramsey 2002). Facilitating the patient to effectively communicate these values is an important part of patient-centred care. Although ‘what matters’ as an outcome of healthcare may differ between members of the healthcare team, the patient has a significant role to play (Ganz 2002, Haywood 2006, Hibbard 2003). Failure to include the patients’ perspective may inadequately inform clinical decision-making, and provides a limited evaluation of healthcare. Whilst rheumatic diseases can affect survival, there is growing evidence demonstrating the significant negative impact on an individual’s quality of life (e.g. Chorus et al 2003, Finlay & Coles 1995). A wide range of health care interventions in rheumatology are concerned with reducing the burden of disease and improving the patients’ experience of ill-health, for example, alleviating pain and improving function, well-being or quality of life. Identifying the most important outcomes of care and the most appropriate methods of assessment is central to effective care delivery. Understanding patient-reported outcome, and the appropriate methods of measuring these outcomes, clearly has an important role to play in modern healthcare.

Across the rheumatic diseases, all therapeutic interventions require rigorous evaluation to provide an evidence-base for policy decision-making and clinical practice. This is of critical relevance to chronic conditions where treatment effects are often subtle and difficult to detect (Hobart et al 2004). Evaluation of healthcare can be used in several ways, for example:

MEASURING HEALTH

Health is a complex construct, the measurement of which should include issues of relevance to patients, healthcare professionals and providers. Measures of health outcome are often categorised as clinical or disease-focused, such as laboratory-based or radiographic assessment; or humanistic or patient-reported, such as health status and health-related quality of life (HRQL) (Ganz 2002, McHorney 2002). These two broad approaches to measurement provide wide ranging and complementary information, often of relevance to both patients and clinicians (Ganz 2002, McHorney 2002). Two classification frameworks are helpful for exploring the different concepts that can be measured: 1) the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (WHO 2001); and 2) Donabedian’s Structure, Process and Outcome (Donabedian 1966).

INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF FUNCTIONING, DISABILITY AND HEALTH

The revised International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) (Stucki et al 2007, WHO 2001) provides a useful framework for understanding disease impact and measuring the outcomes of healthcare. The central concept of ‘functioning’ has been broadened to embrace a biopsychosocial model of health, describing health in terms of biological, psychological, social and personal factors (Dagfinrud et al 2005). Moreover, personal and environmental factors, acting as contextual facilitators or barriers, may further influence the impact of disease and its assessment (Dagfinrud et al 2005, Liang 2004).

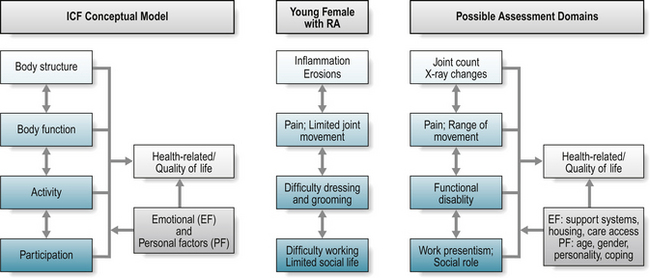

The framework provides a dynamic and interactive model (Fig. 4.1), which complements traditional measures of ‘body structure’ and ‘body function’ (abnormalities or changes in bodily structure or function) with the broader assessment of ‘activity’ (abnormalities, changes or restrictions in an individual’s interaction with the physical context or environment) and ‘participation’ (changes, limitations or restrictions in an individual’s social context; involvement in a life situation, viewed from a societal perspective) (Wade & de Jong 2000).

Applying the relative burden of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) for a young female to the model (Fig. 4.1): RA may cause inflammation and joint damage in the small joints of the hand that can be detected by radiographic evaluation (body structure) and limitation in joint range of movement (body function). These changes may also further impact on an individual’s ability to partake in particular activities, for example, dressing and personal grooming, or playing a musical instrument (activity), and subsequent ability to maintain their desired work role or to socialise with friends (participation). Patients experience the impact of disease as problems relating to their health status and quality of life, and it is usual for a patient to present at a clinic with problems associated with limitation in specific activities or difficulties with participation, as outlined above. The combination of constructs reflects the person in his or her world (Van Echteld et al 2006), providing a systematic and comprehensive, more socially driven, approach to understanding the impact of ill-health (Wade & de Jong 2000).

The impact of ill-health, any associated assessment, and extent of information divulged by patients, may be further influenced by both environmental and/or personal factors, including the individual’s relationship with members of the healthcare team. Health professionals are important facilitators in enhancing environmental factors for people with a rheumatic disease (Van Echteld et al 2006) through, for example, the provision of appliances to facilitate an individual’s capacity for independence in dressing and grooming. Similarly, patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) identified family support as helpful (an environmental facilitator), whereas adverse weather was unhelpful (Van Echteld et al 2006). Personal factors include age, gender, coping mechanisms and personality, and are influenced by environmental factors, the level of social support, and individual factors including level of motivation, expectations for health and healthcare (Liang 2004).

The overall impact of these limitations may be captured within the broader concept of life quality – what do these limitations mean in terms of an individual’s quality of life? Within the proposed framework, quality of life, or health-related quality of life, forms a separate assessment domain (Wade & de Jong 2000). Standardisation of the ICF framework has supported the identification of key areas relevant to the wider understanding of ‘function’ (Stucki et al 2007, Van Echteld et al 2006), facilitated a better understanding and analysis of patient problems, and fostered communication between health professionals (Wade & de Jong 2000). In summary, the ICF provides a useful, conceptual model to guide appropriate assessment of what should be measured to capture the breadth of disease impact; it does not, however, direct how these health constructs, or domains, should be measured (Box 4.1).

BOX 4.1 Study activity: osteoporosis and the ICF framework

What are the presenting complaints of this patient when you review them in a clinic setting? How do these presenting features fit within the revised ICF framework?

What are the presenting complaints of this patient when you review them in a clinic setting? How do these presenting features fit within the revised ICF framework? How well does your routine assessment capture the wider impact of disease and healthcare from the patient perspective?

How well does your routine assessment capture the wider impact of disease and healthcare from the patient perspective?STRUCTURE, PROCESS AND OUTCOME

Traditionally, the quality of health care has been assessed in terms of Donabedian’s classic structure-process-outcome framework (Campbell et al 2000, Donabedian 1966, Mitchell & Lang 2004). Structure embraces the operational characteristics of a service, and includes patient, healthcare professional and organisational variables (Pringle & Doran 2003, Wade & de Jong 2000). Structure also considers the accessibility and relative quality of the many components of health care, for example, how accessible was care for an individual with a rheumatic disease? Process explores how the health care services work in relation to the nature and extent of the patients problem (Wade & de Jong 2000), and includes assessment of the appropriateness of care, location and timing. For example, did an individual with rheumatic disease receive care that was appropriate to their needs, at the right time, and in a suitable location? At the patient level, process measures may also include measures of disease process, such as radiographic imaging, histological and biomedical markers (Bellamy 2005), and patient-reported measures of health status.

Measures of outcome reflect the overall aim of the healthcare service, and may include functional and clinical outcomes, or clinical targets. Although important, global outcome measures such as mortality and morbidity rates are generally irrelevant to a patient’s experience and are generally unhelpful in communicating the broader impact of disease and success of healthcare (Clancy & Lawrence 2002). A necessary change of emphasis in assessment recognises the importance of measuring the quality of survival and the wider impact on an individual’s health-related quality of life. From an individual perspective, important outcomes may assess if, for example, healthcare has minimised their experience of pain and fatigue, assisted the individual in maximising their participation in his/her chosen social setting or work environment, or reduced the distress and pain experienced by the patient’s family and carers (Wade & de Jong 2000). Assessment that embraces the patient perspective has an important role to play in communicating their relative experience of disease and healthcare.

MEASURING HEALTH: THE PATIENTS’ PERSPECTIVE

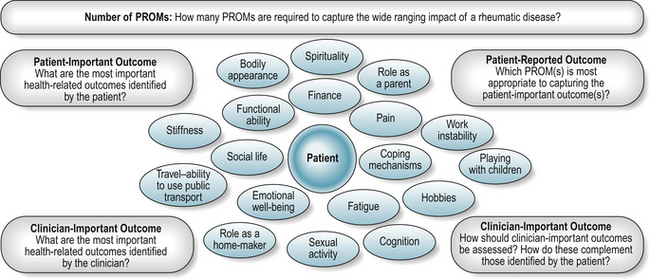

Challenges of including the patient’s voice in the assessment process include identifying the most important outcomes and the most appropriate and acceptable methods of assessment (Fig. 4.2, Box 4.2).

PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOME AND PROMS: DEFINITION

A patient reported outcome (PRO) has recently been defined as ‘any report coming from patients about a health condition and its treatment’ (Burke et al 2006). PRO assessment is therefore broad ranging, and includes health-related quality of life, needs assessment, treatment satisfaction and treatment adherence.

Well-developed, relevant and scientifically rigorous patient-reported measures or patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) provide a measure of an individual’s experiences and concerns in relation to their health, health care and quality of life (Fitzpatrick et al 1998, Ganz 2002). PROMs are largely self-completed questionnaires containing several questions, or items, to reflect the broad nature of health-related concerns. They are available to measure a wide range of health-related concepts such as pain, physical disability, treatment side-effects, satisfaction or experience of health care, health care costs, and quality of life (McDowell 2006). Although variously referred to as measures of quality of life, health-related quality of life (HRQL), or health status, measures of health status often have a narrower focus, for example, the assessment of pain, fatigue and functional disability, than measures of HRQL, which may include a broader range of health-related domains, for example, emotional well-being and work disability. Measures of quality of life should capture all aspects of life, including non-health related issues.

PROM development has traditionally been dominated by clinical experts who, although knowledgeable, cannot communicate the impact of ill-health and treatment in the same way as a patient (Fitzpatrick et al 1998). Furthermore, evidence of discrepant views between patients and health care providers in their assessment of important health outcomes (Hewlett 2003, Kessler & Ramsey 2002, Kvien & Heiberg 2003, Liang 2004) highlights the irrefutable need for simple and effective methods to enhance patient involvement in PROM development and evaluation. Application of the revised ICF framework has supported the comparative evaluation of available PROMs, and highlighted the often limited patient contribution to PROM development, the limited content of widely used PROMs, a lack of precision relating to the concepts assessed, and hence a limited ability to capture the broader concepts of patient participation (Van Echteld et al 2006). Where PROMs seek to communicate the patient voice, methods to ensure that patients reported outcomes embrace patient important outcomes are essential.

Once questions, or items, are generated to reflect a particular construct, such as fatigue, a measurement scale or set of response options are described for each item (Streiner & Norman 2003), such as a series of graded descriptive, or categorical, responses (i.e. no fatigue, mild, moderate, severe, very severe fatigue) with associated numerical values, or a horizontal visual analogue scale (VAS) with descriptive and numerical anchors (i.e. 0 ‘no fatigue’ to 100 ‘extreme fatigue’). The associated numerical scores may then be combined, usually summed, to give a final score. The addition of numerical values does not guarantee that the distance between successive categories is the same, that is, continuous or interval level data, and the majority of measurement response scales produce categorical data on an ordinal level of measurement. However, under most circumstances, and unless score distribution is severely abnormal, data can be analysed as if continuous or interval level data (McDowell 2006, Streiner & Norman 2003).

Proxy completion of questionnaires where relatives or clinicians complete the measure on behalf of the individual can be an important source of information particularly in the case of children (Varni et al 2005), chronically debilitated or cognitively impaired patients (Neumann et al 2000). Discrepancies between a proxy measure of health and that reported by an individual have been observed. Discrepancies are often greater for non-observable constructs such as pain and depression, and less for more observable constructs such as physical ability (Ball et al 2001).

PATIENT-REPORTED OUTCOME MEASURES: TYPOLOGY

Garratt et al (2002) describe four broad categories of PROM: generic, domain-specific, condition or population-specific, and individualised.

Generic

Generic measures contain multiple concepts of health of relevance to both patients and the general population, supporting comparison of health between different patient groups, and between patient groups and the general population (Haywood 2006). Population-based normal values can be calculated for generic instruments which supports data interpretation from disease-specific groups (Ware 1997).

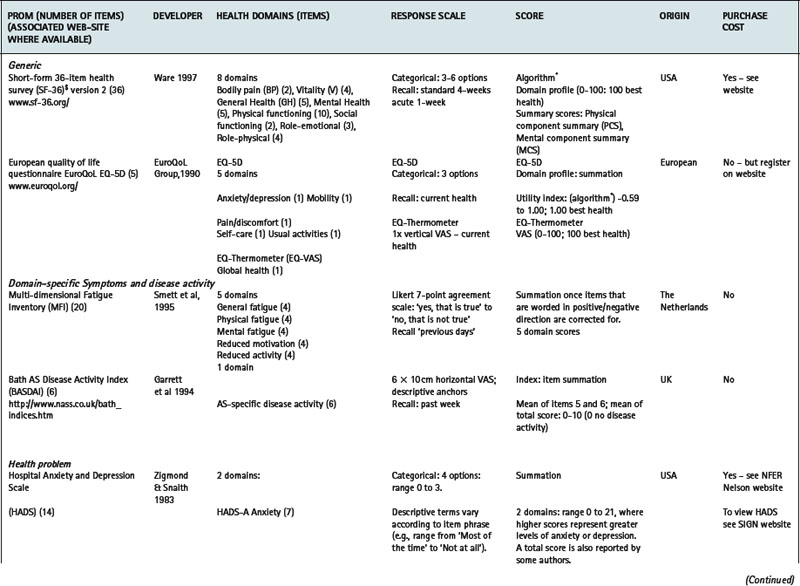

Two distinct classes of generic instrument can be described: health profiles and utility measures. Scores on different domains of health covered by a single health profile are presented separately to support data interpretation, therefore reflecting a clinical perspective. Sometimes an index or summary score may be generated, but proponents of profiles argue that measurement is most meaningful within separate domains (McDowell & Newell 1996). The Short-Form 36-item Health Survey (SF-36) (Ware 1997, Ware et al 2002) (www.sf-36.org) is a widely used example of a generic health profile both generally and in patients with rheumatological or musculoskeletal conditions (Garratt et al 2002) (Table 4.1). The comparison of generic health status between members of the general population, and patients with RA or AS (matched for important factors such as age, gender, demographic, work and disease status) demonstrated that both patient groups had worse levels of physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) health when compared to the general population (Chorus et al 2003). When the two patient groups were compared, patients with RA reported worse levels of physical health, but better levels of mental health than patients with AS.

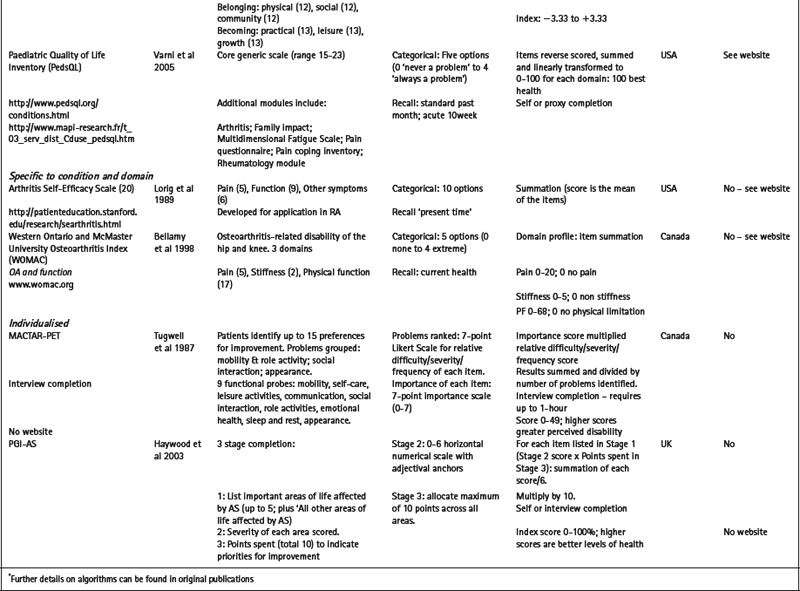

Table 4.1 Selected generic and specific patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) of relevance to the rheumatic diseases

Utility measures incorporate the values and preferences for health outcome generated by the patient (direct weighting), reflecting the individual perspective, or the general population (indirect weighting), reflecting the societal perspective (Fitzpatrick et al 1998). Although utility measures usually include several domains of health, by providing numerical values for health states that use states of perfect health and death as reference values, utility measures can be used to generate single index values that combine health status with survival data – for example, to produce quality adjusted life years (QALYs). The EQ-5D is an example of a utility measure that incorporates indirect valuations of health states (EuroQolGroup 1990) (www.euroqol.org) (Table 4.1). Although widely used in the rheumatic diseases (Brazier et al 2004, Haywood et al 2002, Marra et al 2005), the EQ-5D has been criticised for having both limited item content and response options, and hence may be limited in detecting small, but important, changes in health in people with chronic ill-health (McDowell & Newell 1996), such as rheumatoid arthritis (Marra et al 2005) and ankylosing spondylitis (Haywood et al 2002).

Domain-specific PROMs

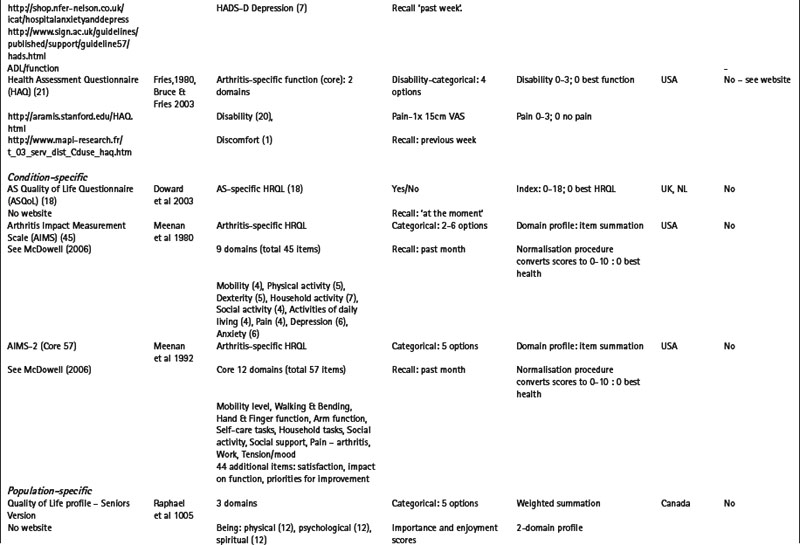

Measures may be specific to a health domain, such as fatigue, for example, the multi-dimensional fatigue inventory (MFI) (Smets et al 1995), or disease activity, for example, the Bath AS disease activity index (BASDAI) (Garrett et al 1994). Alternatively, they may be specific to a health problem, for example, the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Snaith 1983) which is specific to depression and anxiety (Table 4.1), or a described function, for example, activities of daily living (McDowell 2006), such as the health assessment questionnaire (HAQ) (Bruce & Fries 2003, Fries et al 1980) (Table 4.1).

Condition or population-specific PROMs

Alternatively, measures may be specific to a particular condition or disease, for example, the arthritis impact measurement scale version 2 (AIMS2) is specific to people with arthritis and assesses physical, emotional and social well-being (Meenan et al 1992); or to a patient population, for example, the quality of life profile – seniors version (QLP-SV) (Raphael et al 1995) is specific to the assessment of quality of life in older people. Some measures may be specific to a population with additional modules that provide further disease or symptom specific information: for example, the paediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL) (Varni et al 2005) has a core generic scale for the assessment of paediatric quality of life, with additional modules for fatigue (PedsQL multidimensional fatigue scale) and rheumatology-related problems (PedsQL rheumatology module pain and hurt scale) (Varni et al 2007). Numerous measures are specific to a condition and a health domain. For example, the arthritis self-efficacy scale (Lorig et al 1989) is specific to the assessment of self-efficacy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the Western Ontario and McMaster university osteoarthritis index (WOMAC) is specific to the assessment of functional ability in lower limb osteoarthritis (Bellamy et al 1988) (Table 4.1).

Individualised

The majority of conventional PROMs are highly standardized questionnaires with a pre-determined set of items and response options. Although standardized questionnaires often have good measurement properties (Fitzpatrick et al 1998), they may omit issues of importance to individual patients, while containing items of little relevance to others. Measures that adopt a more individualised approach, such as the schedule for the evaluation of individual quality of life (SEIQoL) (McGee et al 1991) and the patient generated index (Martin et al 2007, Ruta et al 1994), support the incorporation an individual’s problems and priorities in the assessment process. Evidence suggests that these measures have enhanced content validity in comparison to more standardized measures (Haywood et al 2003), and that patients’ view them as more valid assessments of health (Neudert et al 2001).

Several individualised measures have encouraging evidence of required measurement properties following completion by patients with a range of rheumatic diseases including the disease repercussion profile (DRP) (RA) (Carr & Thompson 1994), the MACTAR-patient elicitation technique (MACTAR-PET) (RA) (Tugwell et al 1987), the personal impact health assessment questionnaire (PI HAQ) (RA) (Hewlett et al 2002) and the PGI (AS) (Haywood et al 2003) (Table 4.1).

The respondent burden associated with individualised measures is often greater than that observed for more standardized approaches, and several measures require interview administration. As a consequence, the application of individualised measures in clinical research is limited (Patel et al 2003). However, the enhanced content validity and relevance to patients suggests that individualised measures may have an important role to play in routine practice (Greenhalgh et al 2005, Marshall et al 2006) but to date there are no published trials that rigorously evaluate the role of individualised measures in this setting (Marshall et al 2006).

Condition-specific, scientifically rigorous PROMs that have involved patients in item generation have greater clinical relevance, are more acceptable to patients, and more responsive to change in health than generic measures (Wiebe et al 2003). However, the broad content of generic measures supports the identification of co-morbid features and unexpected treatment side-effects that may not be identified by specific measures. Furthermore, certain generic measures, such as the EQ-5D (EuroQoL Group 1990) and the SF-6D generated from the SF-36 version 2 (Ware et al 2002, Marra et al 2004, 2005), can inform economic evaluations of service delivery. The combination of generic and specific measures has been recommended in health outcome assessment (McDowell & Newell 1996), and together are an essential element in the development of evidence-based healthcare. Combined, the evidence supports determination of the absolute and comparative effectiveness of interventions, their marginal relative benefits, and the economic implications of long-term therapies. However, the optimal combination of measures has not been determined in a way that makes it easy to implement this recommendation across diverse patient groups. A fundamental consideration is the appropriateness of each measure to the proposed application.

PROMs: QUALITY ASSESSMENT

The measurement of patient-reported outcome in healthcare has enjoyed increasing attention over the last 25 years and as a result several hundred measures are now available. For many of the rheumatic diseases there is often a choice (Garratt et al 2002). However, the quality of PROMs varies widely, and guidance or consensus on selection is often lacking. The appropriate selection of an outcome measure should be guided by a wide range of measurement (reliability, validity, responsiveness to clinically important change, precision, interpretation) and practical issues (appropriateness, acceptability, feasibility). These concepts have been detailed by several authors (Fitzpatrick et al 1998, Haywood 2008, McDowell 2006), and are summarised in Tables 4.2 and 4.3.

Table 4.2 Criteria for selecting patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): Measurement properties

| CRITERION* | DEFINITION | EVALUATION |

|---|---|---|

| Reliability (OMERACT filter ‘discrimination;) | ||

| Temporal stability-are the results stable over time? | Test-retest reliability assesses score temporal stability (correlation coefficient); scores should remain unchanged in stable patients | |

| Are the scores internally consistent? (multi-item measures only) | Internal consistency reliability evaluates the ability of items to measure a single underlying health domain (Cronbachs alpha). | |

| Reliability estimates > 0.70 and 0.90 recommended for group and individual assessment respectively | ||

| Validity (OMERACT filter ‘truth’) | ||

| Does the PROM measure what it claims to measure? | ||

| Content validity – how well do items cover the important parts of health to be assessed? | Qualitative appraisal of item content. | |

| Face validity – what do the items appear to measure? | How were items generated? Role of clinicians, patients etc? | |

| Qualitative appraisal of item content. | ||

| How were items generated? Role of clinicians, patients etc? | ||

| Criterion validity – how well does the measure perform against a gold-standard measure of the same construct? | Quantitative evaluation-comparative evaluation (if gold-standard available) | |

| Construct validity | ||

| – does the PROM show convergence/divergence with appropriate variables? | Quantitative comparison with other variables (health, clinical, socio-demographic, service use) – e.g. what are the hypothesised and actual levels of correlation with other variables? | |

| – does the PROM show divergence between groups of patients? | Quantitative evidence of discriminative ability between defined patient (extreme) groups. For example, pain levels between active and non-active disease groups/general population. | |

| – is there evidence to support the hypothesised domain structure? | Internal construct validity (dimensionality)-statistical methods such as factor analysis | |

| Responsiveness (OMERACT filter ‘discrimination;) | ||

| Does the PROM detect change over time that matters to patients? | Change in health following an intervention or over time. | |

| (sometimes referred to as ‘sensitivity to change’) | Distribution-based assessment-relates score change to some measure of variability; e.g. Effect Size statistics. | |

| Anchor-based assessment-relationship between score change and external variable: e.g. patient’s perception of change | ||

| Precision | ||

| How precisely do the PROM numerical values relate to the underlying spectrum of health, and discriminate between respondents in relation to their health? | Data quality and precision influenced by item coverage and response categories; where more than 20% of respondents have maximum bad or good health scores, score distribution indicates floor or ceiling effects respectively, and hence a lack of precision | |

| (sometimes referred to as ‘sensitivity’) | ||

| Interpretability (included in OMERACT filter ‘feasibility’) | ||

| How interpretable are the scores? | Distribution-based – describe change over time and group differences that are likely to be clinically meaningful. | |

| How do the scores relate to meaningful or worthwhile change in health? | Anchor-based-relate score change or differences between groups to external variables to estimate ‘Minimal Important Difference’: e.g. patient or clinician perception of change | |

OMERACT headings (Bellamy 1999)

* Criterion headings informed by Fitzpatrick et al (1998) and Haywood (2007).

Table 4.3 Criteria for selecting patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs): practical properties

| CRITERION * | DEFINITION | EVALUATION |

|---|---|---|

| Appropriateness | ||

| How well does the intended purpose of the PROM meet the intended application? Is it relevant? | For example, if the primary intent of the intervention is to reduce pain, pain should be an important component of a primary outcome measure | |

| If the patient has indicated that their ability to engage in paid employment is their most important outcome, how appropriate is the selected PROM to communicate this outcome? | ||

| Acceptability | ||

| Is the PROM acceptable to patients? How willing or capable of completing the PROM are the patients? Is it relevant? | Most readily assessed through completion/response rates, and missing values. Difficult to evaluate directly. Focus groups with patients are useful for exploring acceptability. Extensive involvement of patients during PROM development should improve acceptability. | |

| Feasibility (OMERACT filter ‘feasibility’) | ||

| What time and resources are needed to collect, process and analyse the PROM? | Specific to the requirements of clinicians, researchers, and other staff. | |

| Is the PROM self-completed or does it require interview administration? How long does completion require? Is completion appropriate to the available setting? | ||

| Are instructions for completion and scoring provided? Is special equipment, for example, computer completion, required or available for completion and scoring? How accessible is such equipment? | ||

| How quickly can scores be generated? How are results presented to clinicians and/or patients? – for example, graphic representation of scores. | ||

| If the scores are required for face-to-face discussion during the patient consultation, how quickly can the PROM be scored, analysed and fed-back to the healthcare professional and the patient? | ||

* Criterion headings taken from Fitzpatrick et al (1998) and Haywood (2007)

The field of rheumatology benefits greatly from the work of Outcome measures in rheumatology and clinical trials (OMERACT: www.omeract.org). OMERACT recommend the application of a slightly different set of criteria, or ‘filter’, when assessing the appropriateness of PROM for application in defined settings (Bellamy 1999) (Tables 4.2, 4.3). The filter summarises measurement and practical properties under three headings: 1) Truth: is the measure truthful, does it measure what it purports to measure? Is the result unbiased and relevant? This concept relates to issues of face, content, construct and criterion validity; 2) Discrimination: does the measure discriminate between health states or situations that are of interest? The situations can be states at one time (for classification or prognosis) or states at different times (to measure change). The concept is related to issues of measurement reliability and responsiveness; and 3) Feasibility: can the measure be applied easily, given constraints of time, money, and interpretability? The concept of feasibility is an essential element in measurement selection.

It is essential that users are aware of these key properties to support appropriate selection, interpretation and communication of data generated. In selecting a PROM, the user must decide what exactly is required in terms of the proposed application, appropriateness to the patient (population) and setting, and the feasibility of application and scoring. In short, an appropriate balance between required detail, accuracy of assessment and the burden of collecting the information must be sought (McDowell 2006), as summarised in Table 4.4.

Table 4.4 Assessing the appropriateness of a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) to the proposed application

| QUESTION | WHAT SHOULD BE CONSIDERED? |

|---|---|

| What is the proposed application for the PROM? | |

| In what setting is the PROM to be applied?-routine practice; clinical research; health policy; quality of care evaluation | |

| Will the data to be used to assess current disease state? | |

| Will the data be used to assess disease progress over time? | |

| Will the data be used to evaluate a programme of care? Are group level or individual level data required? | |

| Will the data be used to communicate the impact of healthcare to interested stakeholders? What outcomes are viewed as important indicators of care? | |

| Will the PROM be used to enhance patient involvement in the consultation process? | |

| What patient characteristics will influence PROM selection? | |

| Disease-specificity and co-morbidity | |

| Age – ability to self-complete; need for assistance; need for proxy completion. | |

| Level of disability – ability to self-complete; need for assistance; need for proxy completion | |

| Tolerance for completion – the relative length of PROM and associated respondent burden | |

| What is the assessment time frame? | |

| Will the assessment be cross-sectional, or longitudinal with multiple assessment points? | |

| What is the PROM recall period and how does this relate to the proposed application? | |

| Will the PROM be used to assess acute symptoms? This requires measurement that is responsive to clinically important change over relatively short time-frames | |

| Will the PROM be used to assess the long-term impact of a condition? The longer-term effects of disease impact requires measurement that is sensitive to small changes over relatively long time-frames | |

| How complex/simple should the assessment be? | |

| What detail is required? How broad ranging is the assessment provided? | |

| To whom will the results of the assessment be communicated? What is the important outcome to be communicated? | |

| How feasible is it to include the assessment of Body Structure, Body Function, Activity and Participation? | |

| What is the relevance of the proposed assessment to the clinical question? | |

| Is the data easily interpreted? For example, does the PROM produce a single index scores and/ or a profile score over several domains. | |

| What facilities are required to support the assessment? | |

| In what setting is the PROM to be applied? Clinic-based; trial-based completion; patient self-completion | |

| What support is required for PROM completion and scoring? For example, paper-based completion; electronic data capture and scoring; computer-based support etc. | |

| What is the associated cost of PROM completion, scoring, data feedback and administration support; plus computer support where appropriate. | |

| What facilities are required/available to support the real-time feedback of scores to inform shared clinical decision-making. | |

GUIDANCE FOR PROM SELECTION IN THE RHEUMATIC DISEASES

Working groups

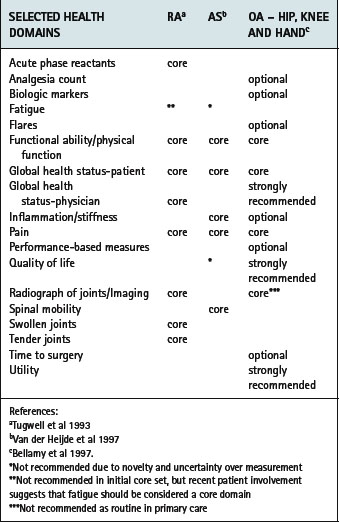

Several resources now exist to support healthcare professionals in the selection and application of PROMs. OMERACT consists of several international working groups dedicated to improving measurement across the rheumatic diseases. In recent years a wider range of health professionals and patients have participated in the process, with a significant impact on the identification of patient-important outcomes. Using a data-driven, iterative consensus approach, core assessment domains have been recommended across a range of conditions including RA (Tugwell & Boers 1993), AS (van der Heijde et al 1997,1999), osteoarthritis (Bellamy et al 1997), osteoporosis (Sambrook 1997), systemic lupus erythematosus (Smolen et al 1999), systemic sclerosis (Merkel et al 2003) and fibromyalgia (Mease et al 2007) (Table 4.5).

Table 4.5 OMERACT recommended core domains for rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and osteoarthritis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree