Fig. 9.1

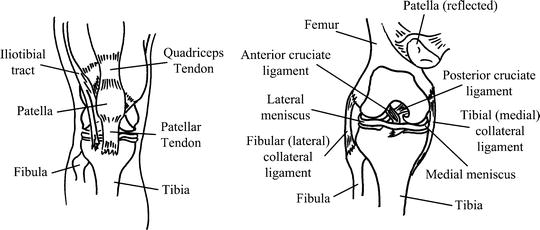

Surface anatomy of the knee – medial view

Fig. 9.2

Surface anatomy of the knee – anterior view

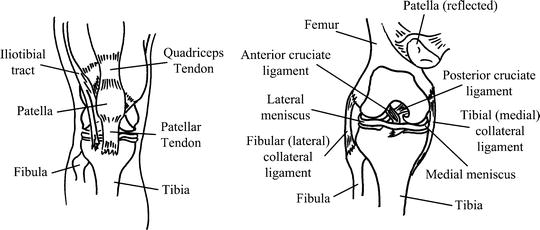

There are four major ligaments of the knee, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), which inserts on the anterior tibia; the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), which inserts on the posterior portion of the tibia; the tibial (medial) collateral ligament; and the fibular (lateral) collateral ligament. The ligaments passively support the knee joint. The menisci located medially and laterally function as shock absorbers, improve stability, and provide nutritional support to the knee [1]. The basic anatomy of the knee is shown in Fig. 9.3.

Fig. 9.3

Basic external and internal anatomy of the knee. Left. External view. Right. Internal view

Red Flags

1.

An acutely effused knee with history of trauma: fracture must be ruled out (see below).

2.

A red, hot knee joint. While other pathologies may exist, with an isolated red, hot joint, consideration must be given to septic arthritis.

3.

Patients with systemic symptoms or multijoint involvement. These patients are likely to have a systemic condition and should be appropriately evaluated.

General Approach to the Patient with Knee Pain

When a patient presents to a clinician with knee pain, a rapid diagnosis can be facilitated by asking a few simple questions. Age, mechanism of injury, location of pain, history of swelling and the reason the patient presented today at this particular place and time all provide great clues as to the pathology present. For example, a preteen with no trauma who presents with nonspecific knee pain on a Friday afternoon urgent care clinic because the discomfort was too great to wait for an appointment with his primary healthcare provider would raise one’s suspicion for an unusual problem. When physical exam reveals that the pain is reproduced by internal rotation of the ipsilateral hip, the diagnosis of a slipped femoral epiphysis should be strongly considered. A positive straight leg test would point toward spinal pathology that can masquerade as leg pain.

Determining what conditions worsen the pain and which relieves the pain is also important. For example, increased pain at rest and decreased pain with activity point to a non-musculoskeletal etiology of the patient’s problem.

Determining the mechanism of injury is also essential. If a patient falls directly on their patella and if their foot is plantar flexed, there is an increased risk of a PCL tear as opposed to a patient who falls with his foot dorsiflexed, where there is an increased risk of a patellar fracture or a resultant osteochondral lesion of the posterior aspect of the patella. Patients who injure their knee when it is in complete extension have an increased risk of ACL or meniscal tear, whereas patients who fall on a flexed knee have an increased risk of a PCL tear. There are a number of protocols that can be helpful in determining if the patient is in need of radiography. See Table 9.1 [2].

A patient with a history of fall or blow to the knee who has one or more of the following should receive imaging with radiography: |

1. Age 355 years |

2. Isolated tenderness of the patella |

3. Tenderness at head of fibula |

4. Inability to flex knee to 90° |

5. Inability to bear weight (four steps) both immediately and in the emergency department or at initial evaluation |

When examining the patient, noting the position of rest is helpful in determining what is wrong with the knee [3]. A patient with a large knee effusion would not be able to flex their knee past 90°. A large effusion indicates intra-articular pathology. In addition, it is quite common in patients with an acute ACL tear and a significant joint effusion to splint their knee in 10–15° of flexion. Those with osteochondral irritation of the posterior aspect of the patellae will tend to keep their leg in extension at rest. Asking the patient to use their index finger to point out where they are having discomfort can also be useful, i.e., a young female with Osgood–Schlatter syndrome points to her tibial tuberosity.

It is of utmost importance that the knee be evaluated without clothing covering it. Patients should be placed in shorts or in some type of gown so that their modesty is preserved. Conditions, such as shingles or a red hot joint, cannot be evaluated unless the patient is properly exposed during the examination.

Common Clinical Presentation

Anterior Knee Pain

Anterior knee pain is one of the most common causes of patients presenting to their primary healthcare provider. Almost all of these patients can be treated nonsurgically, and so a good physical examination is necessary to identify the cause of the anterior knee pain and guide treatment accordingly. The generic diagnosis and treatment of patellofemoral syndrome is often unsatisfactory to the patient and the healthcare provider. Extensor mechanism pain can be caused by a number of conditions; if all are grouped into one diagnosis and treated the same, the patient will have a suboptimal outcome. The patient’s trunk and lower extremity strength needs to be evaluated. A good way to check this is to have the patient stand on one leg and try to do a slight deep knee bend. If the patient has pain when performing this test, the test becomes invalid; however, if the patient can squat without pain, the test is valid and the clinician should observe to see if their trunk leans forward or their knee goes into valgus. These two findings uncover muscular hip weakness. The ability for the patient to maintain neutral spine position has a profound effect on lower extremity dynamic posture. This can be evaluated by having the patient lay supine on the table, and while the examiner puts their hand behind the patient’s back, ask the patient to press the examiner’s “hand against the table” by extending their back. This is easily done when the patient’s knees are flexed 30° to 60°.

Palpation of the bony prominences in the pelvis can rule out apophyseal injuries in the adolescent patients. Palpation of the patient’s quadriceps muscle bilaterally is important to check for atrophy and loss of tone. If present, this infers a chronic process that needs to be addressed by strengthening exercise.

The patella should be evaluated after the trunk and proximal lower extremity have been evaluated as described above. The position of the patella should be noted with the patient sitting with 90° of knee flexion. If the affected patella is sitting “too high” compared to the opposite side, this may indicate that the patella tendon is ruptured. If the patella sits “too low,” this can indicate that the quadriceps tendon is disrupted. Pain caused by compression of the patella indicates potential pathology in the articular cartilage on the posterior aspect of the patella. It should be noted that patellofemoral crepitus without pain is part of the aging process of the knee.

If the patient has had a history of a patellar dislocation or subluxation, they may have a positive apprehensive sign. This test is best done with the patient lying supine with their leg resting on the sitting examiner’s leg at approximately 20° of flexion so the patient relaxes the quadriceps muscle. The examiner then pushes the patella laterally, and if the patient stiffens up and resists this motion, this is suggestive of patellar subluxation. Patients who have had recurrent subluxation or have catching in their knee should be considered for referral for surgical evaluation.

Pain with palpation of the tibial tuberosity can be decisive in diagnosing apophysitis in preadolescent patients. Tenderness over the patellar tendon particularly at the inferior pole can indicate patella tendinopathy, which is common in athletes that require a lot of leaping. This is often referred to as “jumper’s knee.” Pain with palpation posterior to the patella tendon may produce tenderness or crepitus. This is the area of Hoffa’s fat pad which can be injured after the patient undergoes arthroscopy. Also, palpating toward the medial aspect of the patella may reveal a thick and tender plica which is a normal synovial fold that can become irritated and cause patellofemoral pain and dysfunction.

Most patients can be reassured that with a good home program of icing, simple isometric quadriceps strengthening with straight leg raises, hip abductor strengthening, the use of over-the-counter pain medication (acetaminophen or naproxen), and time, their symptoms will resolve. It is important, however, to note that this treatment usually takes 4–8 weeks before the patient notices much of a difference. The use of an anterior knee sleeve or patellar taping by the properly trained clinician or physical therapist may speed up this process. Initially, focus is on quadriceps and hip abductor strengthening but then progression is to strengthening for musculature of the lower extremity and trunk to ensure lasting symptom relief. These patients will not tolerate open chain exercises due to increased force generated on the patellofemoral articulation (exercise in which the foot is not in contact with another object during the whole exercise cycle such as knee extensions). However, closed chain exercises are encouraged. (The foot is in contact with the surface during the whole exercise cycle such as leg press, bicycling, elliptical, and swimming.)

Acutely Effused Knee

When assessing a patient with an acutely effused knee, a number of points should be kept in mind. The patient is oftentimes in pain or anxious, and the examiner should take their time in a private setting to evaluate this properly. Many times having the patient lay in a comfortable position with a pillow or some type of prop under their knee allowing their knee to flex about 30° can assist in examining the patient. If the knee is already tightly effused, many of the tests that have been described become invalid. Any type of systemic symptom such as fever, chills, etc. should alert one to possible sepsis. Crystal-induced arthritis can occur, particularly in patients over the age of 40, and should be considered in the proper setting. Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis can present in children initially with a significant knee effusion. If trauma to the knee has occurred, four possible conditions should be evaluated.

Trauma to the Knee

Subluxed/Dislocated–Relocated Patella

The first one is a subluxed or dislocated–relocated patella. If the patient’s knee is in a semi-extended position, the posterior aspect of the patella is not engaged with the distal condyles of the femur and so the patella can be in an “at-risk” position for either subluxation or frank dislocation. This may happen if there is a mismatch of the bony parts such as a high riding patella or the lateral condyle of the femur that has failed to form completely so that the femoral groove is pathologically “shallow.” The patient’s mechanism of injury generally involves twisting along with the knee bending into a valgus position causing the patella to sublux or dislocate laterally. When this happens, the posterior aspect of the patella may be damaged which can lead to loose body formation. For this reason, x-rays including a patellar sunrise view are recommended in this setting. An excellent test to rule this condition out is the patellar apprehension test as described above (Fig. 9.4). If the radiograph is negative, the patient can be treated with a knee sleeve, ice, weight bearing as tolerated and rehabilitation focusing on quadriceps strengthening to enhance dynamic stabilization of the patella. Recurrent subluxation or patients that complain of physical catching of the patella or locking with the joint with activity should be referred to an orthopedic surgeon.