Chapter 7 The Forearm, Wrist, and Hand

The importance of the wrist and hand is evidenced by the fact that the rest of the upper extremity functions primarily to place the hand in a position where it can operate most effectively. Treatment of the wide variety of disorders that occur in the hand requires an understanding of its complicated anatomy and functional physiology.

Anatomy

SKIN, FASCIA, AND NAIL

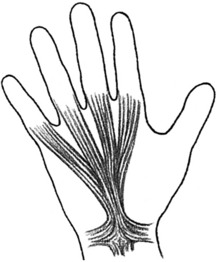

The skin on the dorsum of the hand is loose and overlies a subcutaneous space through which pass many veins and most of the lymph vessels of the hand. This abundance of lymph vessels accounts for the dorsal lymphedema that commonly occurs secondary to infection in the palm or fingers. The palmar skin, however, is firmly attached to the underlying palmar aponeurosis, which is continuous with the palmaris longus tendon (Fig. 7-1). This thick fascia sends extensions into the fingers and protects the important deeper structures of the hand. It may become nodular and shortened in Dupuytren’s contracture.

BLOOD SUPPLY

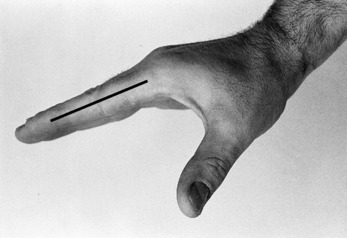

Most of the blood supply to the hand enters on the palmar aspect through the radial and ulnar arteries. Each of these arteries terminates in a superficial and a deep branch. The superficial branches join to form the superficial palmar arch, which is located at the level of the base of the first web space. The deep palmar arch, located 1 cm proximal to the superficial arch, is formed by the junction of the deep branches. The arches are named for their position relative to the flexor tendons. Many branches and anastomoses from these arches provide the blood supply to the fingers and hand. In the fingers, digital vessels (and nerves) lie just ventral to the flexor skin crease of the interphalangeal joints (Fig. 7-2).

MUSCLES OF THE HAND

Motions of the wrist and fingers are controlled by groups of muscles that are classified as either intrinsic or extrinsic. Intrinsic muscles arise within the hand and are responsible for the delicate movements of the fingers. Thenar refers to intrinsic muscles of the thumb. Hypothenar refers to those on the ulnar side of the hand. Extrinsic muscles are those that take origin within the forearm.

EXTRINSIC MUSCLES

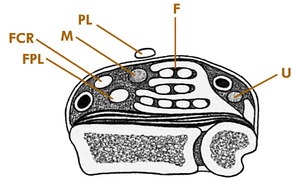

Nine finger flexors and the median nerve pass into the hand through the carpal tunnel beneath the transverse carpal ligament (Fig. 7-3). Five deep flexors pass to the distal phalanx of each finger and thumb, and four superficial flexors pass to the middle phalanx of each finger. Each of these finger flexors can be tested individually (Fig. 7-4).

The extensor tendons pass dorsally over each finger and thumb and insert into the phalanges. They extend the proximal phalanges and assist the intrinsic muscles in interphalangeal joint extension. The thumb extensors are easily palpated at the anatomic “snuffbox.”

NERVE SUPPLY

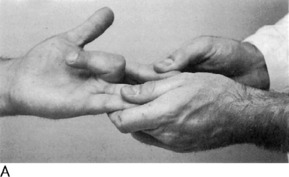

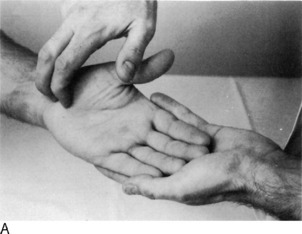

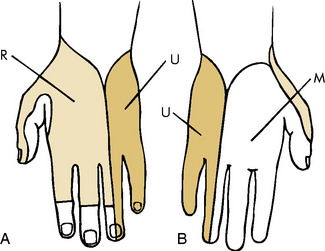

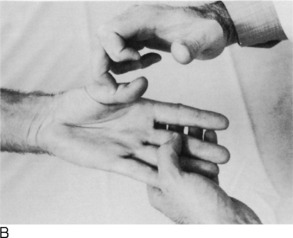

The ulnar nerve provides the motor supply to all of the intrinsic muscles of the hand, except the two radial lumbricals and the thenar muscles. It also provides sensation to the entire ulnar 1½ fingers (Fig. 7-5). Its function is easily evaluated by testing finger abduction and palpating the belly of the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Fig. 7-6).

Fig. 7-5 Dorsal (A) and palmar (B) sensation of the hand. R, Radial nerve; U, ulnar nerve; M, median nerve.

Fig. 7-6 A, Testing for ulnar motor function. B, Testing for median nerve function by determining thenar muscle strength. C, Testing for radial nerve function by examining wrist extension against resistance.

Roentgenographic Anatomy

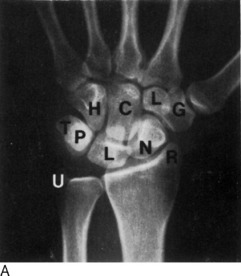

The 27 bones of the hand are visualized by anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique roentgenograms when appropriate (Fig. 7-7).

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Sometimes, a combination of neck and hand pain can develop, especially in patients who suffer from degenerative cervical disc disease. This is termed the “double-crush syndrome” lesion and results from nerve compression at two separate levels, the neck and the wrist. This suggests that proximal compression may decrease the ability of the nerve to tolerate a second, more distal compression.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The onset is usually spontaneous, with gradually increasing pain and tingling in the hand. Nocturnal pain is common and is frequently the reason the patient seeks medical attention. This may be caused by a slight increase in swelling at the wrist with inactivity or perhaps as a result of wrist flexion at night. Pain may radiate proximally into the forearm and even as high as the shoulder. Numbness and tingling occur along the median nerve distribution, but the sensory impairment rarely involves all 3½ fingers supplied by the median nerve. Often, only the long and index fingers are involved. A sense of weakness and clumsiness in the use of the hand is common. All of these symptoms may be precipitated by various manual activities such as typing or painting. They frequently subside after shaking and moving the hand or allowing it to hang downward. The patient often describes “poor circulation” and “stiffness,” but the hand is usually warm, and the motion is full. These latter symptoms are probably caused by the numbness. Physical examination may reveal some sensory disturbance along the median nerve. Tinel’s sign and Phalen’s maneuver are often positive (Fig. 7-8). Atrophy of the thenar muscles is seen in cases of long-standing duration.

Roentgenograms of the wrist are helpful in ruling out local bony abnormality. Nerve conduction studies may be of benefit but are frequently unnecessary in classic cases. Delayed electrical conduction across the wrist is usually present. Electromyography is generally not required. Some error may exist in electrodiagnostic testing, and it should not be the sole guide to diagnosis and treatment.

TREATMENT

Ganglion

Ganglions are soft tissue lesions that are commonly found in the extremities. They are always found adjacent to a joint or tendon sheath. The cause is unknown, but myxoid degeneration of connective tissue and repetitive trauma with chronic irritation are possible causes. The cyst contains a very thick mucinous material and usually has a stalk that can be traced to a tendon sheath or joint.

CLINICAL FEATURES

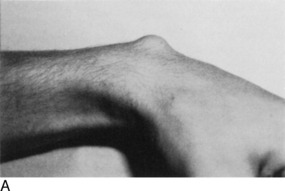

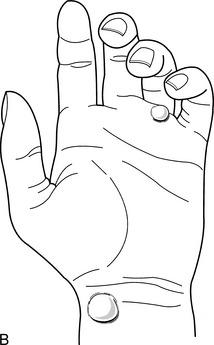

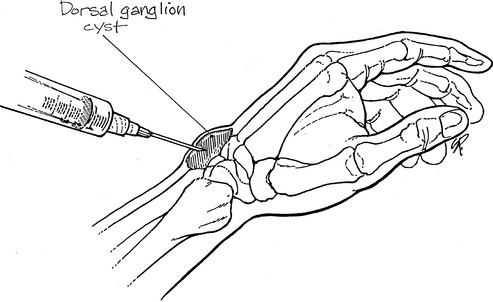

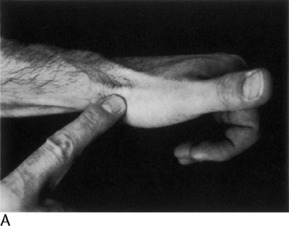

A history of trauma is rarely elicited. Local pain and a feeling of weakness may be noted, but many are asymptomatic. The mass may change in size, with this change often being related to the level of activity of the patient. Ganglia are most common on the dorsum of the wrist. They are more prominent with the wrist flexed and are usually freely movable (Fig. 7-10).

TREATMENT

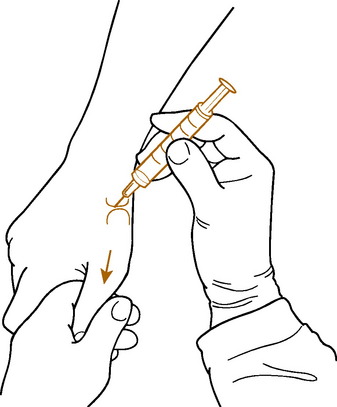

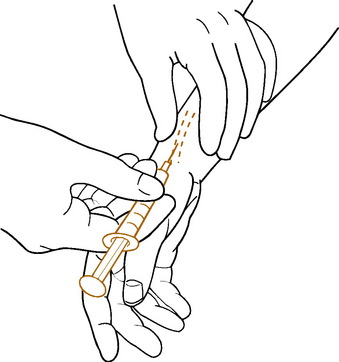

Simple observation is recommended if symptoms are minimal. Ganglia resolve spontaneously in approximately 40% to 50% of cases. A cure may be effected by aspirating or puncturing the cyst in multiple areas and injecting it with a steroid compound (Fig. 7-11). A large (18-gauge) needle is required to aspirate the thick gel. A compression pad is then applied over the lesion for 48 to 72 hours. Recurrence is common.

If symptoms persist, excision of the cyst may be indicated. The recurrence rate is 5% to 10%.

Degenerative Arthritis

Although osteoarthritis of the wrist and hand is much less common than in the lower extremities, it is sometimes more disabling. In the hand, it is 10 times more common in the females than males, and the most common area of involvement is the trapeziometacarpal or “base joint” of the thumb (Fig. 7-12). Involvement at the base joint of the thumb is particularly bothersome because of the tremendous mobility required by this joint in daily use. Sometimes deformity of this joint even develops the appearance of a “mass” because of osteophyte formation, swelling, and subluxation. The arthritis is considered “primary” in most cases but can also develop secondary to fractures and other joint injuries. When the distal interphalangeal (DIP) joints become involved with arthritis, persistent nodular swellings called Heberden’s nodes may develop. Similar lesions at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints are termed Bouchard’s nodes. Occasionally, mucous cysts also develop at these interphalangeal (IP) joints.

TREATMENT

Treatment is similar to arthritis elsewhere. Anti-inflammatory medication, intermittent splinting, moist heat, and occasional local cortisone injections are usually successful in temporarily relieving symptoms (Fig. 7-13). Cystic lesions may be aspirated but should not be drained open. Patients with refractory symptoms should be referred. Arthroplasty and arthrodesis are occasionally necessary to control pain.

Dupuytren’s Contracture

CLINICAL FEATURES

The disorder is usually painless. Age of onset is usually between 40 and 60 years. Deformity and interference with the use of the hand by the flexed, contracted fingers are the most common complaints. The process usually begins on the ulnar side of the hand, often starting at the ring finger. An isolated nodule may appear in this area that eventually hardens and later disappears. The overlying skin becomes adherent to the fascia, and a strong fibrous cord develops that extends into the finger (Fig. 7-14). In the later stages of the disorder, the cord may begin to contract and pull the finger into flexion. Multiple fingers may be affected.

Stenosing Tenosynovitis

This common condition of unknown origin may develop from overuse or direct trauma. The resultant inflammation and irritation hinder the normal gliding motion of the tendon. Most cases are primary (idiopathic), although the condition can develop in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Several distinct syndromes can be described, depending on the site of involvement.

DE QUERVAIN’S DISEASE

Tenosynovitis frequently occurs in the first dorsal extensor compartment of the wrist (Fig. 7-15). The extensor pollicis brevis and abductor pollicis longus occupy this compartment and are involved where they cross over the radial styloid.

TREATMENT

Treatment in mild cases includes nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), immobilization, avoidance of the offending activity, and steroid injections into the tendon sheath (Fig 7-16). Braces or other immobilizing devices should always include the thumb as well as the wrist. Moist heat is applied as necessary for comfort.

TRIGGER FINGER AND THUMB

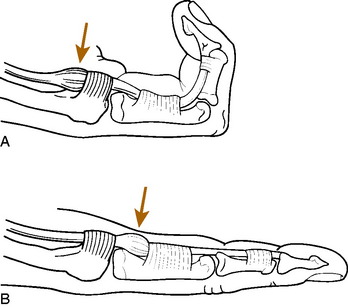

If swelling of the flexor tendon and sheath occurs, passage of the tendon through the constricted sheath may become difficult (Fig. 7-17). This may result in snapping or “triggering” of the affected finger at the MP joint as the swollen, nodular tendon passes through the constricted sheath. The symptoms are frequently worse after rest and improve with active use of the finger. The effect of the triggering itself is transmitted distally to the DIP joint. The finger may even lock completely in either flexion or extension. If the digit locks in flexion, manipulation may be required to extend the finger, a maneuver usually accompanied by a palpable snap. In mild cases, however, the triggering effect may be subtle. Examination usually reveals tenderness and a firm swelling at the proximal flexor pulley. If multiple fingers are involved, rheumatoid disease should be suspected. A congenital form is occasionally seen in the thumb of children.

Repetitive Motion Syndrome

Some reasons for the controversial nature of the disorder are as follows:

Ulnar Nerve Entrapment (Cubital Tunnel Syndrome)

Cubital tunnel syndrome is the second most common nerve compression in the upper extremity. It may occur from several causes, but the most common is chronic trauma to the nerve where it passes behind the elbow. The nerve is most superficial at this location and is easily subjected to external pressure. Leaning on the elbow or repeated flexion and extension may also be factors in its onset. Elbow synovitis with synovial enlargement and muscular hypertrophy may also cause localized pressure in the tunnel. A cubitus valgus deformity at the elbow secondary to a growth plate fracture or infection may also cause paralysis (“tardy ulnar palsy”) by progressive stretching of the nerve in its groove behind the elbow (Fig. 7-18). The nerve may even sublux in and out of its groove on occasion, thereby giving rise to symptoms.

Clinical Features

Minimal pressure against the elbow may lead to paresthesias and numbness along the distribution of the ulnar nerve in the forearm and hand, mainly the small finger (Table 7-1). Tinel’s sign is often positive. The elbow flexion test may be abnormal. This test is performed by having the patient flex the elbow for 30 to 60 seconds with the wrist extended. This maneuver increases the volume and pressure in the cubital tunnel and may reproduce symptoms. The test is not diagnostic, however, because it may be positive in asymptomatic individuals.

Table 7-1 Differential Diagnosis of Common Causes of Forearm and Hand Pain*

| Disorder | Findings Present | Findings Absent |

|---|---|---|

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Painful paresthesias along portions of median nerve (i.e., palm side of hand). Index and long often only fingers involved. May have night pain in long-standing cases. Pain may radiate as high as shoulder. Tinel’s sign may be positive at wrist. | Pain not worsened by resisted motion or stretching. No symptoms on dorsum of hand. Full range of motion. |

| Tenosynovitis | Pain and tenderness usually well localized to site of involvement. Pain may be reproduced by passive stretch or resistance against movement of affected tendon. May be local swelling. | No paresthesias. Full range of motion. No night pain. |

| Tennis elbow (most common lateral) | Pain may radiate from elbow to forearm and hand. Localized tenderness at epicondyle. Pain aggravated by resisted dorsiflexion of wrist (if lateral). Pain with gripping activities. | Full range of motion, no paresthesias or night pain. |

| Osteoarthritis | Local tenderness, sometimes with swelling of affected joint. Pain with motion. Decreased motion. | No paresthesias. Tinel’s sign negative. |

| Cubital tunnel syndrome | Painful paresthesias along ulnar nerve distribution in forearm and hand. Tinel’s sign may be positive behind medial epicondyle. | Full range of motion. Pain not worsened by resisted motion. No night pain.* |

* Notes: Treatment and workup: 1. NSAID, moist heat, splint, and modification of activities as indicated for 2 to 4 weeks. 2. Roentgenogram, inject (if appropriate), change NSAID for 2 to 4 weeks. 3. Nerve conduction studies, referral as indicated.

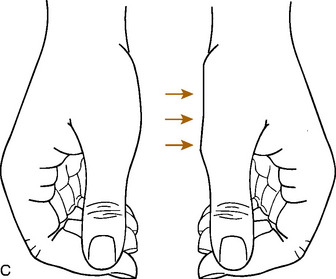

In contrast to ulnar tunnel syndrome at the wrist, symptoms are also present on the dorsum of the hand and ulnar forearm. More severe involvement leads to progressive forearm, hypothenar, and intrinsic motor weakness (weak fanning of the fingers) and atrophy, especially the first dorsal interosseous muscle (Fig 7-19). If the nerve subluxes, the subluxation is usually palpable with elbow flexion and extension. Nerve conduction studies usually reveal delayed conduction at the elbow.