INTRODUCTION

You learned in

Chapter 3 how to determine your patient’s risk level and readiness for exercise. In

Chapters 4,

5, and

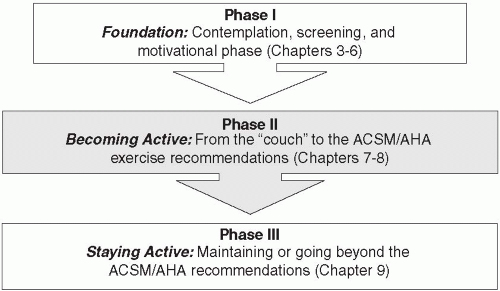

6 you saw the importance of helping your patient lay the groundwork for regular physical activity through mobilizing motivation and developing a strategy for change, thereby beginning the move from Phase I—

Foundation to Phase II—

Getting Active (

Figure 8.1). Now, you are ready to write the Exercise Prescription.

Chapters 3 and

4 discussed medical and mental assessment and screening of patients to determine their readiness to begin and/or maintain a program of regular physical activity. Patients in the Pre-Contemplative Stage—who are not yet ready, willing, and able to begin exercising—are advised of the benefits of exercise. At the other end of the spectrum, patients who already exercise can be counseled to maintain or to increase their exercise, as appropriate, and guided through a program to avoid injury, prevent relapse, and maintain interest in their exercise. Advice and counsel on regular exercise for this group is covered in

Chapter 9. In this chapter, we focus on patients who are

contemplating a program of regular exercise, or actively

planning it. Depending on your type of clinical practice, you may have a significant number of patients who are starting to think seriously about becoming regular exercisers, but are still sedentary or minimally active. It is precisely on these patients, and their health, that your message to initiate and to maintain exercise will have the greatest effect. (See

Figure 7.2.)

Just as in medical school students learn how to write prescriptions for medications, in this chapter you will learn how to write an exercise prescription. Although only certain health care professionals (

e.g., physicians, nurse practitioners, physicians’ associates, and dentists) are licensed to prescribe medications, any clinician can legally write and provide exercise prescriptions to patients. We strongly recommend, however, that healthcare professionals without the legal authority to write medication prescriptions refer patients for a medical evaluation and possibly pre-exercise testing to determine if they have any significant health risks when attempting regular exercise (see

Chapter 3).

When you have a patient who would benefit from a certain medication, it is your responsibility as a clinician to prescribe that medication, especially if

not prescribing that medication would lead to disability, disease, or death. Given the proven health risks of a sedentary lifestyle (see

Table 3.1), the Exercise is Medicine program is based on the concept that it is both the role and responsibility of a clinician to prescribe exercise to patients who would benefit from it. While even low levels of physical activity are better than inactivity, the prescribed program will hopefully guide the sedentary patient to achieve the national recommended levels. The first type of exercise prescription that we will cover is aerobic or cardiovascular exercise. We will then focus on resistance training as a separate type of exercise intervention, and then touch upon flexibility exercises. It is our hope that you will feel competent and even compelled to start writing simple, personalized exercise prescriptions for your patients by the time you finish reading and digesting the information presented in this chapter.

COMPONENTS OF THE EXERCISE PRESCRIPTION

The components of a prescription for medication include the name of the medication, strength or dose, frequency of administration, route, refills, and precautions. The components of an exercise prescription follow a similar format, using the FITT principle:

Frequency,

Intensity,

Time (or duration), and

Type. With a prescription medication, you may start a patient on a small dose and gradually increase the dosage to the full therapeutic level. Similarly, exercise prescription for a sedentary patient will begin at a minimal level, focusing

first on the preliminary aspects of the regular exercise program. From this “small dose” of exercise, the patient, with your encouragement and guidance, will hopefully progress to at least the ACSM/AHA minimum recommended level of physical activity (

1). Thus, in addition to the initial prescribed “dose” of exercise, the exercise

progression is an important part of the prescription. We present three different pathways over which your patients can advance from a sedentary lifestyle to a regularly active lifestyle. First, let us define the different components of the exercise prescription.

Medication Prescription: |

Medicine: |

Ibuprofen |

Strength: |

600 mg tablets |

Route: |

By mouth |

Dispense: |

90 tablets |

Frequency: |

Three times per day |

Precautions: |

Discontinue for stomach upset |

Refills: |

3 |

Exercise Prescription: |

Exercise: |

Walk 30 minutes per day |

Strength: |

Moderate intensity |

Frequency: |

Five days per week |

Precautions: |

Increase duration of walking slowly to avoid injury |

Refills: |

Forever. |

Frequency refers to the number of times the activity is performed each week. There is a positive dose-response relationship between the amount of exercise performed—as the amount (frequency and time or duration) of exercise performed increases, so do the benefits received. Therefore, the more a patient can exercise in a week, both in frequency and total time, the better the long-term outcomes will be for him. After a certain point, adding more exercise stops being beneficial, but this is not usually relevant for patients just beginning an exercise program, and will be discussed in

Chapter 9.

Intensity of the physical activity is the level of vigor at which the activity is performed. There are a number of ways in which intensity can be measured. Some methods are easier to use but are generally less objective, while others are more objective but may require additional equipment or simple calculations.

Table 8.1 provides an overview of some ways to measure exercise intensity.

In general, we recommend using a simple, though less objective, measure of intensity, such as the “talk test” or the Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE). There may be situations in which you want to use or at least to understand the

more objective measures. For a detailed explanation of these measures, please see the Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. In this section, we provide an overview of the more common methods; in the addendum to this chapter, we will review the calculation of percent of maximum heart rate (%HR

max), percent of heart rate reserve (%HRR), percent of oxygen consumption reserve (VO2R), and metabolic equivalents (METS) (see definition in “absolute measures of intensity”).

Subjective Measures of Intensity

The least objective but easiest measure of intensity is the “talk test.” When performing physical activity at a low intensity, an individual should be able to talk or sing while exercising. At a moderate intensity, talking is comfortable, but singing, which requires a longer breath, becomes more difficult. At vigorous intensity, neither singing nor prolonged talking is possible (

2). A similarly easy but more robust measure of intensity is “perceived exertion.” The original perceived exertion scale, the Borg Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE) Scale ran from a minimum of 6 to a maximum of 20. This scale has been simplified to a 10-point scale in which intensity increases from a minimum (level 0) to a maximum (level 10) (

3). We generally recommend using the 10-point RPE scale for patients without significant cardiovascular risk factors.

Physiological/Relative Measures of Intensity

Other more objective measures include percentages of maximal oxygen consumption ([V with dot above]O2max), oxygen consumption reserve ([V with dot above]O2R), heart rate reserve (HRR), and maximal heart rate (HR

max). Some of these more objective measures are used in formal exercise testing. Perhaps the easiest but not the most accurate measure is calculated using a percentage of the patient’s HR

max. For example, exercising at a moderate intensity would be quantified as 64%-75% of HR

max (

4). You determine your patient’s HR

max using the formula 220 minus the patient’s age (220 – age). Although this method is simple, it has a high degree of variability and tends to underestimate HR

max in patients under the age of 40 and overestimate it in patients over the age of 40. This is generally true for both genders (

4). A more accurate but more complicated formula is 206.9 − (0.67 × age) (

5). Depending on the situation, the clinician will need to decide whether ease or accuracy is more important.

Table 8.2 provides the projected heart rates at different ages and different intensities (using the HR

max formula 206.9 − (0.67 × age)).

Absolute Measures of Intensity

Metabolic equivalents (METs) represent the absolute expenditure of energy needed to accomplish a given task such as walking up two flights of stairs. One MET approximates the body’s energy requirements at complete rest. METs are a useful and convenient way to describe the intensity of a variety of physical activities and are helpful in describing the work of different tasks; however, the intensity of the exercise needed to achieve that task is relative to the individual’s reserve (

6). For example, a healthy, active patient may report that climbing the two flights of stairs as light-intensity, while an inactive, chronically ill patient may report that the same task requires vigorous effort.

Table 8.3 demonstrates the energy expenditure to perform different tasks.

In the joint American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and American Heart Association (AHA) exercise recommendations, light physical activity is defined as requiring less than 3 METs, moderate activities 3-6 METs, and vigorous activities greater than 6 METs (

1).

As with other aspects of this book, you and the patient are offered choices. Here, again, which measure of intensity is used is up to the patient and you. For patients at risk for cardiac events, more objective measures may be necessary; while for otherwise healthy, sedentary patients, the easier, more subjective measures will likely suffice. (Refer to

Table 8.1 for intensity measures.)

Time, or duration of the activity, refers to the length of time that the activity is performed. Generally, bouts of exercise that last for at least 10 minutes are added together to give a total time or duration for a given day (

1). For example, a patient who walks 10 minutes to work, and 10 minutes back home, can count a total time or duration of 20 minutes for the day. Note that the exercise recommendations are dosed in terms of minutes of activity.

Type of physical activity: Walking is the most common form of physical activity that sedentary individuals can begin. Walking is a very familiar activity, and one that can easily be incorporated into daily life. However, as

Table 8.3 illustrates, there are a wide variety of other activities that your patient can choose.

As will be discussed further in

Chapters 9 and

10, it is recommended that patients choose more than one activity that they enjoy to provide variety, to utilize different muscles, and to help prevent overuse injuries (

7,

8). When discussing the exercise prescription with your patient, assist her in identifying activities that she is willing to pursue.