Mobilizing Motivation: Behavior Change Pyramid

Edward M. Phillips

OVERVIEW

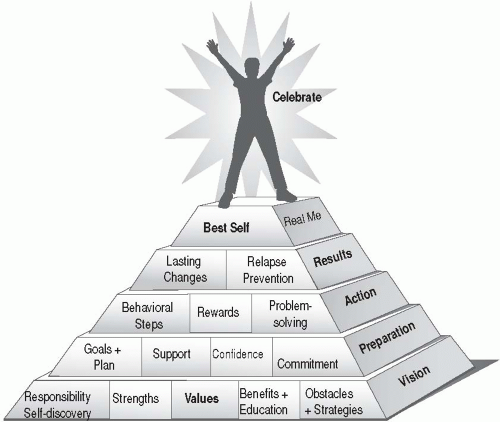

As noted at the beginning of this book, there is more than one way to help patients to mobilize their motivation to make sustained lifestyle changes. In the last chapter we presented what might be called the “shorthand” version. In this chapter we present a more in-depth model. It is called the Behavior Change Pyramid. This model has been developed from evidenced-based principles of Motivational Interviewing, the Transtheoretical Model of Change (also discussed in Chapter 4), Behavioral Psychology, and the new field of coaching psychology. This model guides the clinician to perform more in-depth counseling of patients towards initiating and maintaining the habit of regular exercise, as well as for successfully making other health-promoting behavior changes.

The pyramidal structure of the model is intentional (Figure 6.1). At the foundation level, the patient is asked to create a Vision of a life that includes regular exercise. To make this a sustained lifestyle change, the patient needs to grapple with the fundamental issues of taking responsibility for the proposed change, completing an inventory of personal strengths, coming to grips with the higher purpose or personal values to be met by adopting a more active lifestyle, and developing planning strategies to overcome predictable obstacles. Lastly, the patient is responsible for gathering information and education about the benefits and indeed the risks of becoming more active.

At the second level of the process, the patient is still dynamically thinking and planning and has not yet taken a definitive action, such as joining a gym. At this Preparation stage the Vision is transformed into a realistic plan. The patient garners the necessary support to allow the time and achieve access to exercise along with people on her support team, assesses her confidence level in adopting and maintaining a new physical activity program, makes a verbal or written commitment to cement her resolve, and creates a series of achievable goals and plans toward the eventual objective.

Interestingly, it is not until the third level of the pyramid that it is recommended to the patient to take any definitive Action. Planning and thinking lay the foundation for successfully making behavior change. All too often patients

resolve to quickly change from a sedentary or nearly inactive lifestyle to one that includes daily vigorous exercise. This sudden change from sedentary to vigorous activity is a recipe for post-exercise pain and injury that often leads to resentment, frustration, and quitting. Also, without the necessary planning the patient has no means of support or an alternative pathway to follow should he become injured or run into other obstacles. Once the patient addresses the first two levels of Vision and Preparation, he can take the first behavioral steps of, say, joining a gym, starting another type of exercise program or joining a class or team. At the same time, it is reasonable to start to experiment with exercise, such as walking, alongside the thinking and planning work.

resolve to quickly change from a sedentary or nearly inactive lifestyle to one that includes daily vigorous exercise. This sudden change from sedentary to vigorous activity is a recipe for post-exercise pain and injury that often leads to resentment, frustration, and quitting. Also, without the necessary planning the patient has no means of support or an alternative pathway to follow should he become injured or run into other obstacles. Once the patient addresses the first two levels of Vision and Preparation, he can take the first behavioral steps of, say, joining a gym, starting another type of exercise program or joining a class or team. At the same time, it is reasonable to start to experiment with exercise, such as walking, alongside the thinking and planning work.

Figure 6.1 • Behavior Change Pyramid. From Moore M. Wellcoaches manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009, p. 43. |

In the Action phase, rewards ideally are contemplated and created, but delayed until there is feedback on the first actions. At this Action level the patient now works to learn brainstorming and problem-solving strategies for dealing with unanticipated obstacles such as an injury or inclement weather.

At the fourth level, Results, the patient prepares a back up plan for dealing with possible relapses. At this level the patient learns to incorporate the behavior change as a lasting change or habit in her regular routine. At the fifth and final level, the patient has the opportunity to incorporate the new exercise

routine into her evolving concept of The Best Self. The fulfilled original value established in the base level is supported by the success.

routine into her evolving concept of The Best Self. The fulfilled original value established in the base level is supported by the success.

Patient Vignette

Let’s bring this model to life by considering this patient:

44 year old mother of two, full time office manager

Mild hypertension

BMI = 28

No medications

Sedentary

Your patient decides to take responsibility for a plan to no longer be sedentary. She identifies as a strength her ability to plan ahead. This is the same strength that she uses as a manager in her office. The value of being a good role model for her young children is elicited. As a clinician, you explain the benefits of increased physical activity in bringing down your patient’s blood pressure. Her obstacle of not liking to be uncomfortable during exercise is addressed through education about the marked health benefits of moderate physical activity through daily brisk walks (without getting out of breath).

Setting aside the thirty minutes for her daily walk requires the support of her coworkers and husband. Your patient expresses very low confidence in her ability to immediately reach her ultimate goal of doing 30 minutes of physical activity each day, but has a high level of confidence (8 out of 10) that she can achieve an initial goal of 10 minutes of daily physical activity. Your patient’s commitment to walk with a coworker 10 minutes every day at lunch is cemented by a written agreement signed and included in her medical record. The goals and plan are detailed in your written exercise prescription.

With all of this critical planning and thinking in place, the active next step of commencing her daily lunchtime walks flows seamlessly. As part of the original plan, she rewards herself with a new pair of sneakers after adhering to her daily walks for a full month. Problem-solving skills are called into play when her walking buddy is away from work for several days. During this time she tries listening to music during her walks. After three months of daily walks, your patient begins to incorporate the habit of daily walks as a lasting change. However, when her coworker is transferred to another office, your patient relapses toward inactivity. She reviews her relapse plan and her original values and goals for becoming active. She is also more aware that she feels sluggish and irritable when she skips her walking. She becomes a role model for her children and introduces a new coworker to the daily lunchtime walks. In this ideal progression, your patient moves along in an orderly fashion toward a more physically active lifestyle. The same Behavior Change Pyramid can be applied to dealing with other lifestyle behavior changes addressing, for example, nutrition, weight management, stress management, or tobacco use.

It should be noted that however simply we present this model, your patient’s experience is not likely to be so straightforward. For most people, behavior change does not follow a linear pathway in which one proceeds from the bottom directly to the top of the pyramid. Your patients can cycle up and down the five levels sometimes for years before incorporating a lasting change into what finally becomes their new self-concept. On the other hand, some simple health-promoting behaviors such as drinking two extra glasses of water per day may be quickly incorporated.

The Behavior Change Pyramid can also be used to determine the missing or weak building block that undid a prior attempt to become active. Your patient will commonly report prior periods of physical activity that ended with the onset of poor weather (not planning for obstacles), progressing too quickly in a running program and becoming injured (not adhering to a plan for small steps), or actually achieving the original value such as becoming fit for a special event and then having no reason to continue exercising after that achievement.

Now that we have covered the general principles of the Behavior Change Pyramid, let’s address in more detail the particular issues that can arise at each stage of the process and how the clinician can help patients to initiate and maintain an active lifestyle.

VISION LEVEL

Self-Responsibility

This concept is deceptively simple to both the clinician and the patient. In the predominant model of medical care, the clinician is the expert. In a life-threatening emergency, for example, the clinician is appropriately entrusted to, hopefully, save the patient’s life. Lifestyle change, however, occurs in the context of myriad small decisions made by the patient throughout the day. The clinician is not there, for example, to remind the patient to use the stairs or to go to the gym after work. This gateway of self-responsibility into the Behavior Change Model is strategically placed because it provides the opportunity to triage the patient’s level of readiness for making the proposed change.

At the outset, the self-responsibility box of the pyramid screens for those patients who are ready, willing, and able to commit to making a series of small changes in their daily physical activity level. To be successful your patient must, with your guidance, take personal responsibility for determining what change she will make, when she will do this, and why she will alter her current habits. To be successful, the patient needs to internalize the responsibility for change, rather than look externally for a quick fix, such as the latest exercise gadget advertised on television that guarantees a weight loss of 20 pounds in 4 weeks.

If your patient is not yet ready to take responsibility for making a certain behavior change in one way, he may be willing to take responsibility for making such a change in a different way. For example, the patient may not yet be ready to take responsibility for setting aside the time for leisure-time scheduled exercise, but may be able to commit to the lifestyle approach of slowly increasing the amount of physical activity he does during the course of the day. However, if the patient is not ready to accept responsibility for making any change at the current time, as the clinician you can still provide support and helpful information, such as the benefits of physical activity for his particular circumstance, which may help him to make the desired change somewhere down the road.

This initial block on the Behavior Change Pyramid also presents the clinician with the opportunity to share the responsibility with the patient. You will appropriately advise and coach your patient toward a lifetime of regular exercise; however, your patient will rightfully need to assume the expert role in determining what strategies will most likely support this transition, for him- or herself. As we discussed in Chapter 2, not all clinicians will be comfortable with making this transition.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree