The ethical goal of professional practice: a caring response

Objectives

• Identify how care is the goal of professional ethics activity.

• Describe what mastery entails within the health professional and patient relationship.

• Define patient-centered care.

• Describe how the concept of rights enhances the understanding of what a caring response entails.

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

a caring response

care

mastery

claim

patient-centered care

technical competence

compassion

professional responsibility

due care

accountability

ethical standard

responsiveness

right

human rights

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapter

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| Code of ethics | 1 |

| Personal integrity | 1 |

Introduction

The goal of professional ethics is to arrive at a caring response in situations you encounter in the course of carrying out your professional role and its functions. Obviously, a health professional must thoroughly grasp what a caring response looks like. Its shape is determined by the character of the health professional and patient relationship. Specific forms it takes depend on the activities in which you engage as you carry out the tasks of your chosen profession. Sometimes the care is offered on a one-to-one basis, but often it is offered as one member of the team providing diagnostic or treatment interventions. If you, the professional, pursue a lesser goal than a caring response, or a misguided one, the relationship becomes distorted and results in that patient being given short shrift. This is not surprising because all good relationships present certain “problems” or “challenges” that require caring attention. In this chapter, we present the idea of a caring response for close examination, but this is not the only opportunity you have to consider it. Looking ahead, in Chapter 3, you will be introduced to ethical challenges that present themselves in three major forms or prototypes: moral distress, ethical dilemmas, and locus of authority challenges. Each calls for you, the professional, to be guided by the goal of a caring response.

Caring is essential to the mastery of your professional identity. In general, when one speaks of mastery or expert practice, it refers to successfully having prepared to recognize, give considered attention to, and be able to fully address a challenge, with its resolution the ultimate ideal. In the health professions, your mastery is affirmed only when the patient experiences your response as a caring response insofar as it took the two of you as far as possible toward the ideal of resolving the problem that brought him or her into your life. This is not a new idea. In fact, a recent review article in a major medical journal traces a long history of care as the central feature that divides the mere science of medicine from its essential quality.1 Moreover, the author shows that recent physiologic and neuro-imaging study results show positive findings in patients who experience personal engagement with a health professional as a result of the latter’s attitudes and conduct characteristic of care. This author concludes that a caring response is fundamental to both the art and the science of effective health care interventions. In Chapter 4, you will learn some of the ethics approaches and theories that, over the ages, have been developed to help you gain mastery of the attitudes, skills, and knowledge that equip you to find a caring response that benefits the persons involved. After these introductory chapters, you will have many opportunities to consider different types of situations in which you are required to determine what a caring response involves in each instance. To get you started, consider the following story, which highlights some personal, professional, and societal moralities that you learned in Chapter 1, and the challenges that Pat Jackson, a physician assistant, is encountering as she goes about trying to live by her intention to promote a caring response.2

Many issues can be raised in this story, but your opportunity here is to focus on your opinion about how Pat’s mandate to provide a caring response to Mr. Sanchez should have been achieved. Because you have not yet been introduced more formally to the idea of a caring response, we ask you to rely on your everyday understanding.

Reflection

Do you believe that when Mr. Sanchez first came to the clinic Pat treated him with the full attention consistent with your idea of how a caring professional should respond?

Most readers probably can see some aspects of Pat’s situation that could lead to her devoting less than her full professional attention to Mr. Sanchez. If you do, what are they?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

When Mr. Sanchez returned, Pat hesitated to share her misgivings with him or his foreman. In your opinion, do you think her sources of hesitance have sufficient weight to override her concern that she is being dishonest by withholding some information from him when in fact she is an honest person?

Jot down some thoughts about your answer and how they help support your understanding of what a caring response would look like in this situation.

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

As in many ethical challenges, you may find yourself seeing two sides of the coin and realize that each has a pull on your moral sensibilities. We will discuss this at more length in Chapter 3.

The patient as focus of a caring response

A caring response does not always mean that you will be able to completely resolve the conflict of claims on you, but it does require you to put your priority to optimizing the positive results and minimizing damage to the patient. What do we mean by a “claim?” A claim is a request made verbally or nonverbally by virtue of the expectations people have of your professional role. It says, “Give me your attention!” You know that your role will involve many types of relationships, with patients or clients and other times with families, professional team members, research subjects, policymakers, or the public. And the list is not complete if you fail to include your relationship with yourself and your own health! Each and every one of the parties you encounter will come with claims on your time, services, expertise, or other type of attention. From time to time, you will find yourself torn between more than one claim on your care, just as Pat did. She understood that her patient Mr. Sanchez had a strong claim on her to be treated with the best attention possible; but still, when she realized she may have been negligent in her treatment of him, some other claims on her also raised their head. For one thing, she knew the value of her clinic’s services in this community and that her presence as an essential new addition on the health care team was a boost to the overall effectiveness of the clinic. She must not compromise that effectiveness. She cared about her colleagues and their heavy workloads, so she felt the need to reflect on the negative effect it might have if their load was increased because she was shunned by patients when the word got out that she was not competent. She was also sensitive to the bigger role of her clinic in providing quality care to a previously underserved Hispanic community in the area and wondered if her admission might undermine their trust in the clinic. Finally, she put into the mix the desire to be caring of herself by honoring her wish to participate in a social event on this Friday night in her newly adopted town. All of this was waging war with her personal value of honesty.

Reflection

Stop right here and think about your day so far. What conflicting claims on your attention have you already faced?

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

Conflicting claims are part and parcel of everyday life. But Pat’s professional role helps her to set priorities in relation to Mr. Sanchez. Her primary concern must be the well-being of the patient under consideration. At the same time, Pat’s commitment to honesty, one part of her personal value system, tends to tip the scales in the direction of finding a way to share the information with Mr. Sanchez. This course of action not only keeps the patient in center focus but also allows her personal integrity to be honored. How, when, and where it should be shared requires her to bring other character traits such as compassion and courage into play as she attempts to minimize possible deleterious effects this information may have on him, the clinic, or his ethnic community. She will be wise to engage the services of her colleague who can speak Spanish and comes from Mr. Sanchez’s ethnic group himself.

Patient-centered care

Patient-centered care, or client-centered care, is a term adopted in the health professions’ clinical and ethical literature to emphasize the imperative that professionals keep a focus on the well-being of the whole person. Nursing and medicine have led the way in developing the concept, but almost all health professions have adopted it in principle.3 Entire models of the health professional and patient relationship have been built around this notion, and you likely will learn one or more of them in your professional preparation. The central concept that runs through these models is that patient’s values, concerns, and preferences have moral weight in the everyday clinical decision-making process. Although the terms health care and managed care may have the term “care” embedded in them, they may simply mean dealing with patients in a technical or aggregate sense. For this reason, clinicians and ethicists add “patient-centered” as the orienting point on their moral compass that always brings the focus back to what matters to the patient and what the health professions have to offer.

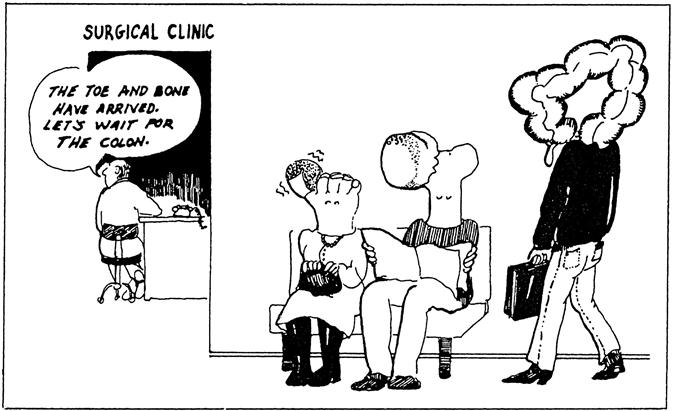

You can easily see that patient-centered care is highly individualized, tailored to fit each patient. This focus of attention is frequently challenged in an era of clinical specialization and sophisticated medical technology. Clinical procedures often are so specialized that a particular disease, symptom, body part, or biologic system can become the focus of attention. The dehumanizing effect that a fragmented focus has on both the health professional and the patient is illustrated in Figure 2-1.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree