Fig. 4.1

Surface anatomy of the elbow – lateral view

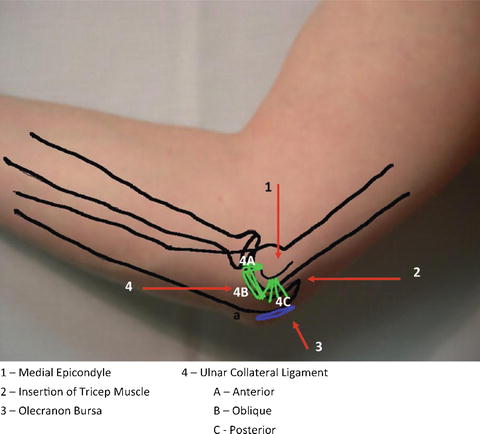

Fig. 4.2

Surface anatomy of the elbow – medial view

Fig. 4.3

Skeletal anatomy of the elbow – lateral view

Normal range of motion of the elbow is 0° (full extension) to 135° (full flexion). Flexion and extension are controlled by the biceps and triceps muscles, respectively. The elbow also rotates 0–180° with supination and pronation. Supination (palm up position) occurs with activation of the biceps muscle. The pronator teres powers pronation of the elbow (palm down position).

Three major nerves traverse the elbow: (1) the median nerve crosses medially and can be entrapped in muscle; (2) the ulnar nerve passes medially and posteriorly to the medial epicondyle through the cubital tunnel, another site of entrapment; and (3) the radial nerve descends laterally with a superficial branch that is also prone to injury. The paths of these nerves are shown in Fig. 4.4.

Fig. 4.4

Anatomy of the major nerves crossing the elbow

Red Flags

1.

Decreased range of motion (ROM). Inability to flex or extend the elbow can be indicative of underlying fracture, dislocation, or joint effusion, all of which may be or indicate potentially severe conditions. All patients with true decreased ROM should be thoroughly evaluated, and in most cases, imaging is warranted.

2.

Joint effusion and redness. Swelling of the elbow must be carefully evaluated. Olecranon bursa swelling, located posteriorly over the olecranon, must be distinguished from a true joint effusion, which is intra-articular. Patients with a true joint effusion will often have more diffuse swelling and will also have reduced ROM or significant pain with ROM. While isolated olecranon bursa swelling can be managed by the primary care provider, joint effusions must be further evaluated, particularly for the concern of a septic joint.

3.

Feeling a “pop”/weakness during activity. This can be a sign of biceps tendon rupture. Patients will be tender over the insertion of the biceps. Although ROM may be normal, weakness of the forearm will be evident on exam with flexion and supination. Immediate referral is required for effective treatment; any delay can result in a poor outcome.

General Approach to the Patient with Elbow Pain

When evaluating the patient who presents with elbow pain, it is important to obtain an accurate history. Gathering information about occupational, hand dominance and recreational activity, as well as any recent injury or trauma, is helpful to pinpoint the offending cause of elbow pain and develop a diagnosis. Knowing the onset of pain helps to differentiate a chronic overuse injury from something more acute. Have the patient pinpoint the area of their pain. This is helpful in narrowing your diagnosis: lateral vs medial pain vs pain over the olecranon bursa. Aggravating and alleviating factors are helpful to know. If the patient has weakness, numbness, or paresthesias, these may be clues to nerve entrapment syndromes or cervical radiculopathies.

The physical exam of the elbow should include inspection, ROM testing, strength, palpation, neurovascular exam, and any special testing. The elbow should be inspected for swelling, deformity, and redness. Evaluate ROM for both flexion/extension and supination/pronation, both passive and against resistance. ROM and strength should be compared to unaffected side. Also evaluate flexion and extension of the wrist as the proximal attachment of these tendons is located on the medial and lateral epicondyles, respectively. If the patient has pain at the elbow with wrist movement against resistance, this can indicate a tendinopathy of the flexor tendons if the pain is on the medial epicondyle or of the extensor tendons if the pain is on the lateral epicondyle. Also, palpate the insertion of the biceps muscle, olecranon, and olecranon bursa for tenderness.

Special testing for elbow pain may include Tinel’s test (gently tap over the nerve with your index finger) at the cubital tunnel if having paresthesia into 4th and 5th digits. A positive Tinel’s at the cubital tunnel may be indicative of ulnar nerve entrapment. Radial nerve compression/entrapment should be considered in patients diagnosed with lateral epicondylitis which is resistant to treatment and also if pain is more distal to the lateral epicondyle than expected in lateral epicondylitis. If the radial nerve is affected, pain and weakness may be provoked by resisted extension of the middle finger. A positive test may indicate a radial nerve compression.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree