Abstract

Objectives

This review examines the effectiveness of semantic feature analysis as an intervention to improve naming abilities for persons with aphasia.

Method

A systematic search of the literature identified 11 studies that met the pre-determined inclusion criteria. Two independent raters evaluated each study for methodological quality and assigned appropriate levels of evidence using the Single Case Experimental Design scale. To determine clinical effectiveness, effect sizes using Cohen’s d were calculated if sufficient data were available. Alternatively, percent of non-overlapping data was calculated.

Results

Results indicated that methodologically sound research has been conducted to determine the effectiveness of semantic feature analysis for persons with aphasia using single subject research designs. When using Cohen’s d , the majority of participants showed a small effect size. However, when percent of non-overlapping data was calculated, a large treatment effect was present for the majority of participants.

Conclusions

Semantic feature analysis was an effective intervention for improving confrontational naming for the majority of participants included in the current review. Further research is warranted to examine generalization effects.

Résumé

Objectifs

Cette revue examine l’efficacité de l’analyse des traits sémantiques comme intervention visant à améliorer les capacités de désignation de personnes atteintes d’aphasie.

Méthodes

Une recherche systématique de la littérature a repéré 11 études correspondant à des critères d’inclusion prédéterminés. Deux évaluateurs indépendants ont noté chaque étude en termes de qualité méthodologique et de niveau de preuve en utilisant l’échelle Single Case Experimental Design (SCED). Afin de déterminer le degré d’efficacité clinique, des ampleurs de l’effet utilisant le d de Cohen étaient calculées à condition de disposer d’un nombre suffisant de données disponibles. Sinon, le pourcentage de données mutuellement exclusives était calculé.

Résultats

Les résultats ont indiqué que des recherches méthodologiquement valables avaient été conduites en vue de déterminer l’efficacité de l’analyse des traits sémantiques chez les aphasiques, analyse qui appliquait des plans de recherche centrés sur un sujet unique. Lors de l’utilisation du d de Cohen, la majorité des participants n’ont présenté qu’une petite ampleur de l’effet. Or dès que le pourcentage de données mutuellement exclusives a été calculé, un effet traitement important a été constaté chez la plupart des participants.

Conclusions

L’analyse des traits sémantiques a constitué une intervention efficace dans le cadre de l’amélioration de la désignation par rapport au mot cible ( confrontational naming ) de la majorité des participants figurant dans cette revue. D’autres recherches pourraient examiner des effets de généralisation.

1

English version

1.1

Introduction

Anomia is the most frequent and persisting symptom of aphasia . Anomia occurs secondary to a neurological event (e.g., stroke, brain injury) and inhibits the ability to formulate language, even at the most basic word level. Anomia is a defining feature of aphasia; it extends across multiple subtypes of aphasia and is observed for all grammatical word forms (e.g., nouns, verbs) . Word naming deficits negatively affect people’s ability to communicate their wants and needs and engage in important social settings and activities. In fact, prior research indicates that people with aphasia (PWA) tend to be more troubled by impairments in speaking than in reading, writing, or listening comprehension and impairments in speaking have important effects on how PWA are regarded by others in daily life . Therefore, identifying an effective treatment for the improvement of naming deficits in PWA is critical.

There are a variety of treatment approaches focused on improving expressive language abilities, specifically anomia, in PWA. It is believed that anomia typically results from overarching semantic impairments and reflects an insufficient engagement of the critical features that distinguish concepts from one another . Typically, semantic approaches to treatment are used to target anomia as opposed to phonological approaches. Examples include circumlocution-induced naming , personalized cueing , and semantic feature analysis (SFA) . The focus of the current review is the clinical effectiveness of SFA for the treatment of anomia in adults with neurological injury.

SFA was first introduced by Ylvisaker and Szekeres and later refined by Massaro and Tompkins . It is a commonly used treatment to improve naming and expressive language abilities of PWA by providing an organized method of activating semantic networks . SFA uses a systematic cueing technique whereby PWA are asked to produce words semantically related to the target word they cannot recall . For example, if the target word is “cup”, the cues might involve questions related to its use (e.g., What do you do with it?), its properties (e.g., What does it look like?), where it might be used (e.g., Where do you find it?), what category it belongs to, and what might be associated with it (e.g., What are other things that are similar to it?). Because it is suggested that anomia results from an impaired semantic network, the goal of therapy is to alter the semantic network connectivity through refinement of the damaged network . Hypothetically, SFA improves the retrieval of conceptual information by accessing and refining semantic networks . Increased activation of the semantic network surrounding the target word elevates the likelihood the word will be retrieved and may also aid to repair the damaged semantic system .

A recent review by Boyle examined the effectiveness of SFA. The review included seven studies, and all studies reported positive outcomes for the effectiveness of SFA for improving anomia for individuals with neurological impairments. However, only three reported the magnitude of the treatment effect . A significant limitation of Boyle’s review is that there was no attempt to calculate magnitude of effect using data reported in the included studies. The absence of effect size calculations in the remaining studies made it difficult to conclude the effectiveness of the treatment. Therefore, the aim of the current study is two-fold. First, we extend Boyle’s review by including new research. Second, we apply statistical methods to investigate the magnitude of treatment effect for the included studies in an effort to answer the following clinical question: For patients with non-degenerative aphasia, does semantic feature analysis improve confrontational naming abilities?

1.2

Methods

A search of the literature was conducted to identify studies that investigated SFA as the primary intervention for anomia for PWA. Seven electronic databases were searched through June 2013: Academic Search Premier, AgeLine, CINAHL, ERIC, Medline, PsycInfo, and Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts. An additional search was performed within the American Speech-Language and Hearing Association (ASHA) journals, and references from all relevant articles were examined to identify any other applicable studies. A combination of search terms included: aphasia , semantic feature analysis , language disorder , semantic cues , anomia , language treatment , and naming treatment .

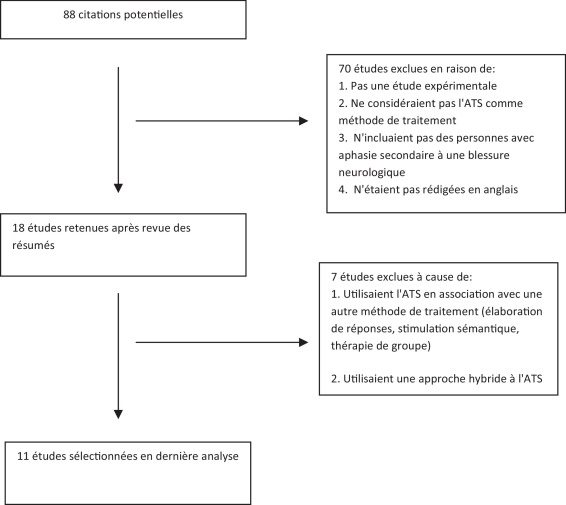

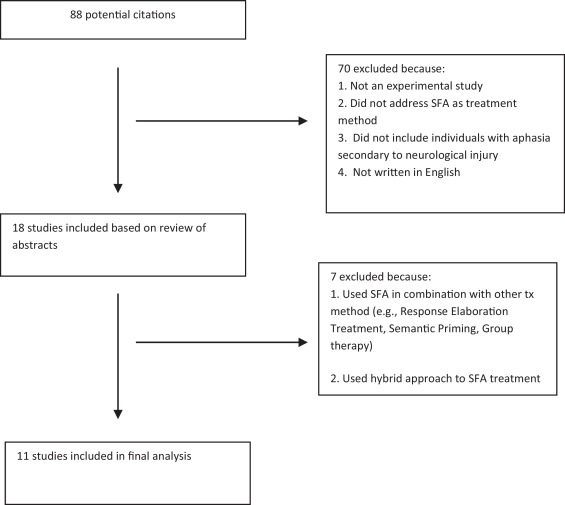

Eighty-eight articles were identified through the search process and the first author subjected these to a title and abstract review, which eliminated 70 articles. A study was excluded from the review if it was not experimental in nature, did not address SFA as a treatment and did not include adults with neurological damage. Studies were considered for review if they were written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal between 1980 and June 2013. The first author reviewed the remaining 18 articles and an additional 7 were excluded as they combined SFA with other treatment methods (e.g., group therapy or semantic priming therapy) or used a hybrid approach to SFA. To be true to the objective of this review, only those studies that used SFA as initially designed by Massaro and Tompkins were included. The process for identifying articles to be included in the evidence-based systematic review is displayed in Fig. 1 .

Two certified and licensed speech-language pathologists critically evaluated the remaining studies for methodological quality. Ten studies were evaluated using the Single Case Experimental Design (SCED) scale . The Marcotte and Ansaldo study was not evaluated using the SCED as it was not a single subject research design study. The SCED is an 11-point scale used to evaluate the methodological quality of single case experimental studies. A perfectly designed and executed study would receive a score of 11. Each independent rater provided a score of 1 if the study adequately addressed the specified quality item or a 0 if it was poorly addressed or not addressed at all. Following independent scoring, inter-rater reliability was calculated using Cohen’s weighted kappa statistic . The weighted kappa is the proportion of agreement beyond chance and takes into consideration the degree of disagreement between two independent raters. The weighted kappa score was .656, which is indicative of good inter-rater reliability . When disagreements were present, an average score was calculated. The first author randomly selected three studies, and re-calculated SCED scores to determine intra-rater reliability. To reduce bias and ensure ratings were not dependent upon one another, re-scoring was completed two weeks after the initial scoring . The weighted kappa score for intra-rater reliability was 1.0, indicating perfect intra-rater reliability.

It is well understood that clinical effectiveness is a critical variable to consider for any treatment. At the same time, it is important to interpret clinical effectiveness in the context of a given study. To strengthen the interpretation of the result of this systematic review, levels of evidence, based on the American Speech and Hearing Association’s (ASHA) levels of evidence hierarchy, were also assigned. The ASHA hierarchy was chosen due to its applicability to the effectiveness of interventions for individuals with communication disorders. Two independent raters evaluated each study and assigned a level of evidence. Following independent rating, the weighted kappa was calculated to assess reliability for assigning levels. The first author randomly chose 30% of the studies for reevaluation, to calculate intra-rater reliability. Inter- and intra-rater reliability were excellent ( k = 1.0).

To determine the clinical efficacy of SFA as a treatment method for aphasia, effect sizes were calculated in those studies that reported sufficient data. Prior to calculation, it was necessary to determine the individual values for the pre-treatment and post-treatment phases for each set of trained items. Therefore, effect size was calculated when response data were presented in whole number increments using a variation of Cohen’s d statistic as described by Busk and Serlin . The following formula was used:

where A 2 and xA 1 designate post-treatment and pre-treatment time periods, respectively, xA is the mean of the data collected during the specific period, and sA 1 is the corresponding standard deviation. Although three post-treatment probes are recommended to provide a more reliable estimate of magnitude of effect, it is mathematically possible to calculate effect sizes when only one post-treatment probe is reported . For the purpose of the present study, effect sizes were calculated when at least one post-treatment probe was reported. The magnitude of change in level of performance was determined according to the benchmarks for lexical retrieval studies described by Beeson and Robey . The benchmarks were 4.0, 7.0, and 10.1 for small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively.

When it was not possible to calculate the d statistic, the percent of non-overlapping data (PND) was calculated. PND is the most widely used method of calculating effect size in single case experimental designs . PND is the percentage of phase B data points (the treatment phase) that do not overlap (in a favorable direction) with phase A data points (baseline or no treatment). To determine the magnitude of effect, benchmarks put forth by Scruggs et al. were used. A PND greater than 90% was interpreted to reflect a highly effective treatment; a PND of 70–90% was considered a moderate treatment outcome; and, a PND of 50–70% was considered a questionable effect. Any PND of less than 50% is interpreted as an ineffective intervention since performance during intervention has not affected behavior beyond baseline performance.

1.3

Results

Ten studies included in the review were single subject research design studies and one was a pre- and post-treatment study. Twenty-four participants were represented in the review. Demographic variables of interest for all participants are presented in Table 1 . There was significant heterogeneity in age and time post onset of participants. Participants ranged in age from 24 to 85 years, with a mean age of 60.75 (S.D. = 14.29). Time post onset ranged from 4 to 187 months, with a mean of 53.74 months (S.D. = 50.44). There were 15 males (63%) and 9 females (37%) represented. Non-fluent aphasia was the most represented subtype in this review ( n = 17; 71%) and seven participants (29%) had fluent aphasia. Twenty-one participants had sustained a single cerebrovascular accident. The remaining three participants presented with aphasia following traumatic brain injury. Of the 11 studies included in the review, aphasia severity was reported in only five studies.

| Study | n | Participant | Age (years) | Gender | Etiology | TPO (months) | Aphasia type | Aphasia severity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyle and Coelho, 1995 | 1 | P1 | 57 | M | L CVA | 65 | Non-fluent | NR |

| Boyle, 2004 | 2 | P1 | 70 | M | L CVA | 15 | Fluent | NR |

| P2 | 80 | M | L CVA | 14 | Fluent | NR | ||

| Coelho et al., 2000 | 1 | P1 | 52 | M | TBI | 17 | Fluent | Moderate-severe |

| Davis and Stanton, 2005 | 1 | P1 | 59 | F | CVA | 4 | Fluent | NR |

| Hashimoto, 2011 | 1 | P1 | 72 | F | CVA | NR | Non-fluent | Moderate-severe |

| Marcotte and Ansaldo, 2010 | 1 | P1 | 66 | M | CVA | 84 | Non-fluent | Severe |

| Massaro and Tompkins, 1994 | 2 | P1 | 24 | M | TBI | 60 | Non-fluent | NR |

| P2 | 28 | F | TBI | 144 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| Peach and Reuter, 2010 | 2 | P1 | 77 | F | L CVA | 4 | Fluent | Mild |

| P2 | 62 | F | L CVA | 14 | Fluent | Moderate | ||

| Rider et al., 2008 | 3 | P1 | 73 | M | L CVA | 26 | Non-fluent | NR |

| P2 | 55 | F | L CVA | 45 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P3 | 62 | M | L CVA | 126 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| Wambaugh and Ferguson, 2007 | 1 | P1 | 74 | F | L CVA | 50 | Non-fluent | Moderate |

| Wambaugh et al., 2013 | 9 | P1 | 85 | M | CVA | 126 | Non-fluent | NR |

| P2 | 59 | F | CVA | 42 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P3 | 61 | M | CVA | 31 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P4 | 47 | M | CVA | 187 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P5 | 59 | M | CVA | 65 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P6 | 52 | M | CVA | 13 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P7 | 66 | M | CVA | 65 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P8 | 64 | F | CVA | 18 | Non-fluent | NR | ||

| P9 | 54 | M | CVA | 9 | Fluent | NR | ||

Scores on the Single Case Experimental Design (SCED) ranged from 8.0 to 10.5 with an average score of 9.3 out of 11 ( Table 2 ). Following SCED scoring, studies were assigned levels of evidence . Ten studies were considered well-designed, quasi-experimental studies and received a level IIb rating. The Marcotte and Ansaldo study was determined to be an observational controlled study and assigned a level III rating. The prevalence of high SCED scores and IIb evidence level ratings indicate strong methodological quality and rigor for the reviewed studies.

| Study | Research design | SCED quality score |

|---|---|---|

| Boyle and Coelho, 1995 | A-B single subject | 8 |

| Boyle, 2004 | Multiple baseline across behaviors | 10 |

| Coelho et al., 2000 | A-B single subject | 8.5 |

| Davis and Stanton, 2005 | Multiple baseline across behaviors | 8 |

| Hashimoto, 2011 | Multiple baseline across behaviors | 8 |

| Marcotte and Ansaldo, 2010 | Pre-/post-treatment study | N/A |

| Massaro and Tompkins, 1994 | Multiple baseline across behaviors | 10 |

| Peach and Reuter, 2010 | Single case time series across behaviors | 10 |

| Rider et al., 2008 | Multiple probes across behaviors | 10.5 |

| Wambaugh and Ferguson, 2007 | Multiple baseline across behaviors | 10 |

| Wambaugh et al., 2013 | Multiple baseline across behaviors | 10 |

Three studies self-reported effect sizes for participants . Effect sizes were calculated for five participants ( Table 3 ). When data was collected and reported on two or more trials of the dependent variable, an average effect size was calculated . A large effect size was present for two participants ( d = 18.76; d = 10.56). A medium effect was present for six participants ( d = 7.95; d = 9.28; d = 7.48; d = 7.79; d = 7.32; d = 9.617). A small effect size ( d = 1.79; d = 3.86; d = 5.54; d = 2.97; d = 1.26; d = 5.01; d = 5.32; d = 6.35) was present for eight participants. The high prevalence of small effect sizes indicates that the treatment was not effective in improving anomia for the majority of participants as it was for these eight participants. Effect size and PND could not be calculated for one participant from the Marcotte and Ansaldo study.

| Study | Participant | Aphasia type | Cohen’s d | PND | Magnitude of effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boyle and Coelho, 1995 | P1 | Non-fluent | 100% | Highly effective | |

| Boyle, 2004 | P1 | Non-fluent | 18.48 b | Large effect | |

| P2 | Fluent | CND | 100% | Highly effective | |

| Coelho et al., 2000 | P1 | Fluent | CND | 100% | Highly effective |

| Davis and Stanton, 2005 | P1 | Fluent | CND | 91.67% | Highly effective |

| Hashimoto, 2011 | P1 | Non-fluent | 10.56 a | Large effect | |

| Marcotte and Ansaldo, 2010 | P1 | Non-fluent | CND | CND | N/A |

| Massaro and Tompkins, 1994 | P1 | Non-fluent | CND | 100% | Highly effective |

| P2 | Non-fluent | CND | 100% | Highly effective | |

| Peach and Reuter, 2010 | P1 | Fluent | 1.79 | Small effect | |

| P2 | Fluent | CND | 85% | Moderately effective | |

| Rider et al., 2008 | P1 | Non-fluent | 3.86 a | Small effect | |

| P2 | Non-fluent | 5.54 a | Small effect | ||

| P3 | Non-fluent | 2.97 a | Small effect | ||

| Wambaugh and Ferguson, 2007 | P1 | Non-fluent | 6.35 b | Medium effect | |

| Wambaugh et al., 2013 | P1 | Non-fluent | 5.32 a | Small effect | |

| P2 | Non-fluent | 7.95 a | Medium effect | ||

| P3 | Non-fluent | 9.28 a | Medium effect | ||

| P4 | Non-fluent | 7.48 | Medium effect | ||

| P5 | Non-fluent | 1.26 a | Small effect | ||

| P6 | Non-fluent | 5.01 a | Small effect | ||

| P7 | Non-fluent | 7.79 a | Medium effect | ||

| P8 | Non-fluent | 7.32 a | Medium effect | ||

| P9 | Fluent | 9.617 a | Medium effect | ||

b Calculated by the author of the present paper, from data provided in articles.

PND was calculated for seven participants. A large treatment effect (PND > 90%) was present for six participants and a moderate treatment effect was present for one participant (PND = 85%). When examining clinical effectiveness using PND, treatment was highly effective for the majority of participants. None of the participants evidenced PND scores consistent with ineffective treatment.

1.4

Discussion

Results indicate that SFA is an effective intervention for improving confrontational naming of items trained in therapy for individuals with non-degenerative aphasia. In addition to self-reported positive outcomes, effect size calculations indicated that there was a medium to large treatment effect for the majority of participants represented in the review. Although findings suggest that treatment was effective for improving confrontational naming of trained items, limited generalization to untrained items and connected speech were reported in many of the included studies. This finding warrants further examination to determine factors that may influence generalization, such as intensity or dosage. There are several limitations to this review, which will be discussed in detail.

1.4.1

Variations in study participants

For the purpose of this study, participants in the acute phase of recovery were included. Although spontaneous recovery could result in favorable treatment results, all participants in the acute phases demonstrated a stable pre-treatment baseline. Additionally, participants in the acute stages of recovery did not demonstrate an abnormally large effect size or PND following treatment, d = 1.79 , PND = 85% , and PND = 91.67% . Although there was considerable variation in the reported time post onset amongst participants, 92% (22/24) were post-acute (more than 6 months post onset). This is not surprising as most single subject research studies in the aphasia literature are conducted with individuals who are significantly post onset in order to achieve a stable series of observations and to control for spontaneous recovery . As a result, the magnitude of effects reported likely underestimates the magnitude of effects possible for individuals with acute aphasia, as more progress and improvement is typically observed in the acute stage of recovery . Furthermore, throughout the aphasia literature, age and time post onset are often cited as significant prognostic indicators for recovery of language abilities . Future studies need to investigate the effectiveness of SFA for various age groups and time post onset of aphasia.

Aphasia type was varied (e.g., anomic, transcortical motor, Broca’s) amongst participants in the study. When divided into the broad categories of fluent and non-fluent aphasia, non-fluent aphasia was the most represented subtype in this review ( n = 17; 71%). Seven participants (29%) had fluent aphasia. Results suggest that the effectiveness of SFA as treatment for anomia may be more effective for persons with fluent aphasias as compared to those with non-fluent aphasias. Previous research suggests that individuals with fluent aphasias demonstrate significant deficits in category knowledge . Thus, treatments targeting category knowledge deficits may be more effective for this group. However, further research is necessary to compare the benefits of SFA for individuals with both fluent and non-fluent aphasias. Consequently, clinicians contemplating SFA as a treatment may need to consider aphasia type.

1.4.2

Variations in the intervention

Clinicians and researchers should bear in mind that SFA is not always conducted using a standardized procedure. For example, some studies reported longer treatment periods while some included more frequent treatment sessions over a shorter duration. In the Rider et al. study, treatment consisted of one-hour sessions two to three times a week for five weeks. Davis and Stanton used a similar treatment protocol with therapy two times a week for six weeks. Further research is warranted to determine the appropriate dosage and treatment duration to determine clinical efficacy. Additionally, some studies targeted atypical exemplars (e.g., egret), while others targeted more typical exemplars (e.g., robin). Standard execution of SFA following the original intent of the treatment, including stimuli and treatment dosage, would allow for the conduction of meta-analysis to more conclusively determine treatment effectiveness.

1.4.3

Variations in outcome measures

There was significant heterogeneity regarding outcome measures used in the included studies. Peach and Reuter examined the effect of SFA on discourse production, specifically verbal productivity (# of words per T-unit) and informativeness (content information units; %CIUs) , as well as naming of untrained items. Because these measures were not directly related to the outcomes of the treatment, it is difficult to calculate meaningful effect sizes. Boyle and Coelho , Davis and Stanton , and Boyle analyzed the percentage of pictures correctly named as the primary dependent variable in the study, but also calculated %CIUs. In addition to these measures, Boyle and Coelho also used the Communicative Effectiveness Index to examine social validity of changes. In addition to percentage of pictures named correctly, Rider et al. also examined lexical diversity ( D ) and performance on standardized language measures, such as the Western Aphasia Battery , Boston Naming Test , and the Reading Comprehension Battery for Aphasia .

1.4.4

Limitations to statistical analysis

The use of a variety of outcome measures makes it difficult to make a definitive decision regarding the clinical impact of the treatment. Therefore, meta-analysis is needed. There are several advantages to completing a meta-analysis . First, meta-analysis allows for the generation of a summary effect by combining studies and establishes a magnitude of treatment effect. It also provides for a determination if the effect is uniform across studies, and if not, provides a mechanism for studying participants’ heterogeneity. Lastly, meta-analysis also allows for comparisons across subgroups (e.g., gender, age, aphasia type, aphasia severity).

A recent review of single subject research design studies found that PND is the most commonly used outcome metric for systematic reviews . However, there are certain limitations of using PND. It is important to note that there are no benchmarks for PND published for studies in aphasia, therefore, it is difficult to estimate magnitude of effect for aphasia treatment, and findings should be interpreted cautiously. Furthermore, we found that PND may overestimate the effect of treatment, when compared to effect size d calculations. For example, Rider et al. reported small effect sizes for three participants. However, after calculating PND, we found a highly effective (PND = 90%), moderately effective (PND = 80%), and questionably effective score (PND = 50%). Similarly, Peach and Reuter reported a small effect size ( d = 1.79) for one participant on verbal productivity during the treatment phase. When PND was calculated, we found a moderate treatment effect (PND = 78%). These comparisons suggest that PND is a more liberal method of analyzing treatment effectiveness. It is important to remember that PND is the percentage of phase B data points (the treatment phase) that do not overlap (in a favorable direction) with phase A (baseline or no treatment) data points. An individual may improve naming ability by 10% on confrontational naming tasks while another individual may improve naming ability by 50%, but would receive the same PND scores if there was no overlap of treatment and baseline data points. Therefore, by its nature, this calculation determines whether there is a treatment effect, but does not fully examine the magnitude of effect. Future research is needed to determine the correlation between PND scores and the d statistic and to determine the reliability of PND as a measure of treatment magnitude in the field of aphasia treatments.

In order to complete a true meta-analysis, effect sizes are required. Because effect sizes are quantified in standard deviation units, they can be compared across studies and combined in meta-analyses . Although effect sizes are now more commonly reported in group studies, they continue to be generally absent in single subject research design studies. When effect sizes are included in published reports, they allow clinicians to develop a sense of the relative strength of the specific instrument . In the present study, only three studies self-reported effect sizes, and only two provided the raw data necessary for precise calculation. Not only would this data provide more conclusive information regarding the treatment effectiveness of SFA, it would also allow for the examination across subgroups (e.g. fluent versus non-fluent, acute versus non-acute). These results would allow us to definitively determine whether SFA may be more effective for individuals with fluent or non-fluent aphasia or for individuals with mild versus moderate aphasia. It is critical that future studies report effect sizes in order to allow for future meta-analysis.

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest concerning this article.

2

Version française

2.1

Introduction

L’anomie est le symptôme le plus fréquent et le plus persistant de l’aphasie . L’anomie survient secondairement à un événement neurologique (AVC, lésion cérébrale…) et inhibe la capacité de formulation de langage, même au niveau des mots les plus élémentaires. L’anomie est une caractéristique qui définit l’aphasie ; elle recouvre de multiples sous-types de celle-ci et concerne toutes les formes grammaticales des mots (noms, verbes…) . Les déficits lexicaux nominatifs déteignent négativement sur la capacité des personnes atteintes de communiquer leurs désirs et besoins et de s’engager et s’intégrer à des activités sociales. Certaines études indiquent que des personnes avec aphasie (PAA) ont tendance à être plus dérangées par leur handicap en expression orale que par leurs handicaps en matière de lecture, d’écriture et de compréhension orale. Qui plus est, leurs difficultés d’expression retentissent sur la façon dont les PAA sont vues par les autres dans la vie de tous les jours . L’identification d’un traitement efficace susceptible de résorber les déficits nominatifs chez les PAA revêt une importance critique.

Il existe déjà un certain nombre d’approches au traitement centrées sur l’amélioration des capacités linguistiques expressives chez les PAA atteintes d’anomie. Elles partent de l’idée que de manière typique, l’anomie est le résultat de handicaps sémantiques globaux et qu’elle est le reflet d’une implication insuffisante des aspects critiques qui distinguent les concepts les uns des autres . De manière générale, dans les traitements ciblant l’anomie les approches sémantiques sont préférées à des approches phonologiques. Parmi les exemples figurent la nomination induite par des circonlocutions , le repérage personnalisé ( personalized cueing ) et l’analyse des traits sémantiques (ATS) . Dans ce recensement, c’est en mettant l’accent sur l’efficacité clinque que nous allons aborder le traitement de l’anomie chez des adultes souffrant d’atteintes neurologiques.

L’ATS fut initialement présentée par Ylvisaker et Szekeres ; par la suite, elle a été développée par Massaro et Tompkins . Il s’agit d’un traitement assez répandu visant en cas d’anomie à améliorer les capacités langagières nominatives et expressives en proposant une méthode organisée d’activation des réseaux sémantiques . L’analyse emploie une technique de repérage dans laquelle on demande aux PAA de produire des mots sémantiquement associés au mot cible qu’ils n’arrivent pas à se rappeler . Par exemple, supposons que le mot cible est « tasse ». Les tentatives de repérage ( cues ) pourraient comporter des questions ayant trait à son utilisation (Qu’est-ce que vous faites avec ?), à ses propriétés (À quoi cet objet ressemble-t-il ?), aux lieux possibles de son utilisation (À quel endroit le trouvez-vous ?), à la catégorie dont il relève et aux associations possibles (À quels autres objets est-il similaire ?). Puisqu’il a été proposé que l’anomie résulte d’un réseau sémantique entravé, le but de la thérapie consiste à modifier la connectivité du réseau sémantique en développent de nouveau le réseau endommagé . De manière hypothétique, l’ATS améliorerait la récupération d’informations conceptuelles en accédant aux réseaux sémantiques qu’elle développerait . L’activation renforcée du réseau sémantique entourant le mot cible augmenterait les chances de récupération du mot et pourrait contribuer à la réparation du système sémantique endommagé .

Une revue récente de Boyle a évalué l’efficacité de l’ATS. Cet auteur a recensé sept études différentes, qui ont toutes rapporté des résultats positifs soulignant l’efficacité de l’ATS en atténuant l’anomie chez les personnes avec des handicaps neurologiques. Cela dit, l’importance ou l’ampleur de l’effet traitement n’est considérée que dans trois des sept études . Une limitation significative de la revue de Boyle concerne l’absence de toute tentative de calculer l’ampleur de l’effet en utilisant les données rapportées dans les études incluses. À cause de l’absence de ce calcul dans les autres études publiées, on peut difficilement conclure à l’efficacité du traitement. Par conséquent, nous avons établi deux objectifs. Premièrement, nous allons élargir la revue de Boyle en évoquant des recherches nouvelles. Deuxièmement, nous allons appliquer des méthodes statistiques en vue de déterminer l’ampleur de l’effet des traitements répertoriés dans les études incluses et de répondre de manière satisfaisante à la question clinique suivante: Dans des patients souffrant d’aphasie non dégénérative, est-ce que l’analyse des traits sémantiques améliore les capacités de désignation par rapport au mot cible ?

2.2

Méthodes

Une revue de la littérature a été effectuée afin d’identifier des études enquêtant sur l’ATS comme intervention primaire en cas d’anomie chez les PAA. Jusque dans leurs versions de juin 2013, sept bases de données électroniques étaient explorées : Academic Search Premier, AgeLine, CINAHL, ERIC, Medline, PsycInfo et Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts. Une revue additionnelle a eu lieu en passant au peigne fin les journaux de l’American Speech-Language and Hearing Association, et les références à tous les articles pertinents étaient également épluchées afin d’identifier encore d’autres études utilisables. Parmi les mots-clés retenus figuraient : aphasie , analyse des traits sémantiques , désordres , trouble du langage , repérages sémantiques , anomie , traitement du langage et traitement nominatif .

Lors de la revue 88 articles ont été identifiés, mais dès que le premier auteur a passé en revue les titres et les résumés, 70 articles ont été éliminés. Une étude a été exclue de la revue :

- •

si elle n’était pas expérimentale ;

- •

si elle n’abordait pas l’ATS comme traitement ;

- •

si elle ne concernait pas des adultes souffrant d’atteintes neurologiques.

Par contre, dans un premier temps les études étaient retenues :

- •

si elles étaient rédigées en anglais ;

- •

si elles avaient fait l’objet d’une publication entre 1980 et juin 2013 dans un journal avec comité de lecture.

Ensuite, le premier auteur a passé en revue les 18 articles restants dont 7 étaient exclus parce qu’ils associaient l’ATS à d’autres méthodes de traitement (thérapie de groupe ou thérapie de stimulation sémantique) ou parce qu’ils employaient une approche hybride à l’ATS. Afin de rester en conformité avec l’objectif de la revue, seules les études abordant l’ATS telle qu’elle avait été initialement conçue par Massaro et Tompkins ont été incluses de manière définitive. Le processus par lequel les articles à inclure ont été identifiés dans le cadre de notre revue systématique fondée sur des preuves est résumé sur la Fig. 1 .