The Direct Lateral Approach for Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty

Timothy E. Ekpo

Adolph V. Lombardi Jr

Case Example

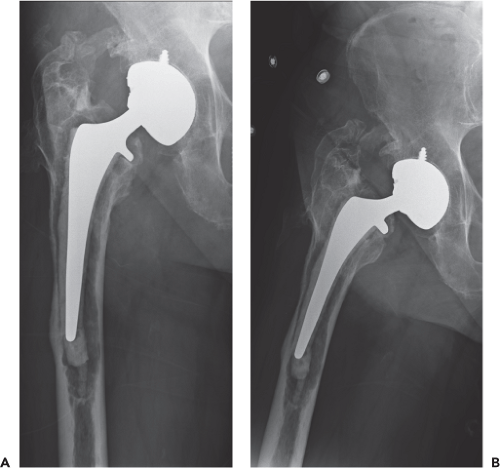

An 84-year-old man was referred to our practice 12 years after undergoing hybrid primary right total hip arthroplasty (THA) via a standard direct lateral approach for an underlying diagnosis of osteoarthritis. The patient was 69 in tall, weighed 185 lb, and had a body mass index of 27.3 kg/m2. He presented with complaints of moderate pain in the groin and anterior thigh, progressive over the past year. The pain was worse with all walking and with standing. He required a walker for ambulation, and his walking distance was limited to two to three blocks. Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the right hip (Fig. 102.1) revealed femoral component loosening with associated osteolysis and near circumferential acetabular radiolucencies.

Introduction

Revision THA can be challenging for any surgeon. However, utilization of a suitable approach and understanding of anatomy and function can help avoid common problems that may occur during surgery. Utilization of approaches allowing for removal of existing components, correction of bony deformity, or malalignment, and exposure necessary to achieve solid fixation of the new prosthesis and restore bone stock deficiencies is paramount. These approaches are usually extensile allowing the surgeon safe access to the planned operative site as well as further proximal and distal exposure as necessary.

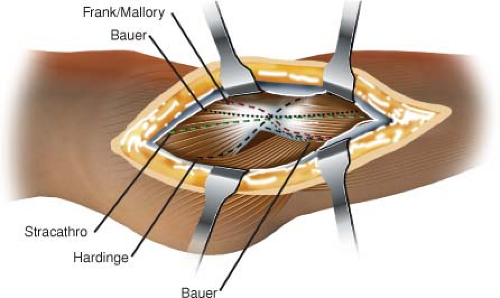

The direct lateral approach to the hip by definition is one in which dissection is made through the gluteus medius and minimus. The direct lateral approach was first described by Bauer and later popularized by Hardinge in 1982 (1,2). Since that time many variations have been described (Fig. 102.2). The original description by Hardinge involved removal of 50% to 60% of the abductors from the greater trochanter. Most modifications from this description vary in the amount of the abductor that is detached from its tendinous insertion, either by electrocautery or via osteotomy. We prefer to use the modification described by Frndak et al. (3) for primary THA, and by Head et al. (4) for revision THA. This variation differs by removal of only 25% to 30% of the abductors, thereby preserving a majority of function and minimizing the occurrence of limp, which has been a criticism of the approach.

Indications and Contraindications

One of the most common complications occurring after revision THA is dislocation. For example, high postoperative dislocation rates have been demonstrated after liner exchange utilizing the posterior approach (5,6). The direct lateral approach has been shown to provide substantial stability which is maintained by preservation of the posterior capsule and short external rotators (7). The stability provided makes the direct lateral approach advantageous for utilization in isolated liner exchange (5).

The direct lateral approach is extensile both distally and proximally, allowing excellent exposure to both femur and acetabulum. Since the distal portion of the incision is centered over the femur, continual extension in the same plane is easily performed for additional exposure and visualization down to the knee joint. Because of the ease of extension, implant or cement removal necessitating extended trochanteric osteotomy and even total femur replacement can easily be performed utilizing the same incisional approach. The utility of this approach allows superior direct visualization of the acetabulum in a more anatomic view than other approaches. The exposure provided by this approach is thought to allow for more accurate cup placement, thus minimizing the risk of dislocation. Through this approach, acetabular revision requiring particulate and structural bone grafts, porous metal augments, jumbo cups, offset liners, reconstructive cages, or triflange acetabular components can be performed without limitation of exposure.

We currently utilize the direct lateral approach for the vast majority of our revisions, including those where a previous surgery was performed through an anterior or posterior approach. There are few contraindications to the utilization of the direct lateral approach. However, it should be noted

that when there is a complete absence of posterior structures, one may consider using the posterior approach for subsequent reconstruction of these structures such as if plating of the posterior column is planned.

that when there is a complete absence of posterior structures, one may consider using the posterior approach for subsequent reconstruction of these structures such as if plating of the posterior column is planned.

Surgical Technique

After anesthesia is provided the patient is placed supine on the table and assessed for leg length discrepancy. The patient is then placed in the lateral decubitus position with the operative side facing the surgical field. There are numerous hip positioning devices available for stabilizing the pelvis. We prefer the use of a peg board for positioning as it safely accommodates patients of all sizes. When using this method, it is important to make sure all pegs are properly padded next to the patient, and the anterior pegs are placed appropriately so they do not impede hip flexion, adduction and internal rotation during dislocation of the hip. After the patient is prepped and draped, leg length is once again assessed (Fig. 102.3). We prefer using the well leg down technique (8). This simple yet accurate test is performed by

placing the heels together and palpating the relationship of the knees to one another.

placing the heels together and palpating the relationship of the knees to one another.

Figure 102.2. Illustration comparing multiple variations of the direct lateral approach. The difference is best noted in the location at which the abductor musculature is split. |

The surgeon typically stands posterior to the patient and the first assistant stands anterior to the patient. Previous incisions are noted and demarcated prior to sterile prep. We use a laterally based incision and whenever feasible incorporate as much of the previous incision as possible. This incision should be situated directly over the greater trochanter (Fig. 102.4). The length of the incision should be proportional to the extent of the revision procedure planned. The dissection continues through the skin and subcutaneous tissues to the level of the tensor fasciae latae. The fasciae latae is then incised along the line of the incision. During revisions where a previous direct lateral approach was used, it is best to carefully identify the plane between the fascia lata and vastus lateralis distally. Cautious dissection proximally should follow because there may be adhesions between the tensor fasciae latae and underlying structures including the gluteus maximus and gluteus medius. The lateral aspect of the femur can be exposed by retraction anteriorly and posteriorly of the myofascial sleeve. Dissection commences distally and posterolaterally in the vastus lateralis. The vastus lateralis either can be split or elevated off of the femur anteriorly from its intermuscular septum; we prefer the former technique.

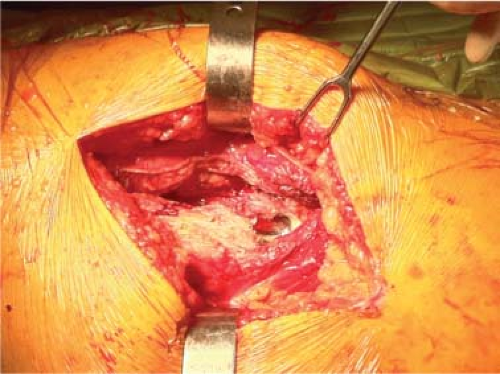

Dissection then extends proximally to the level of the vastus tubercle. Using Bennett-type retractors the vastus lateralis is reflected anteriorly. Starting at the level of the vastus tubercle dissection proceeds anteriorly and cephalad extending in the direction of and elevating the gluteus medius, minimus, and capsule from the anteromedial aspect of the femur. The dissection into the gluteus medius and gluteus minimus occurs at an interval determined by the location of the neck of the femoral prosthesis. This typically leaves approximately 70% to 75% of the abductor mechanism attached to the greater trochanter (Fig. 102.5). Proximal dissection into the abductor should be limited to 3 to 4 cm. This cautious approach will avoid the superior gluteal nerve, thereby preserving innervation to the anterior-most fibers of the gluteus medius and minimus, which are kept in continuity with the vastus lateralis.

Dislocation is facilitated with the use of a bone hook placed around the prosthetic femoral neck. While the surgeon applies distal and lateral traction, the assistant flexes, adducts, and externally rotates the operative extremity. Dislocation of the hip may be difficult at times. When this occurs, we have found it helpful to release the capsule from the posterior superior rim of the acetabulum, further release the vastus lateralis, or release the distal posterior medial capsule and iliopsoas tendon insertion from the lesser trochanter. Once dislocation is accomplished, a wide Hohmann retractor is placed beneath the greater trochanter to elevate the proximal femur and provide enhanced exposure. A second retractor can be placed along the posterior neck of the femur to further enhance visualization. Finally, a third retractor is placed in the piriformis fossa, retracting the abductor complex and protecting it from damage (Fig. 102.6). Together, this permits visualization of the entire proximal femur allowing for debridement of bone and soft tissue, which assists in stem removal.

If the stem still cannot be removed, an episiotomy of the proximal femur can be created. This episiotomy should be made in a manner that it would serve as the anterior border of an extended trochanteric osteotomy if needed later (Fig. 102.7). After its completion, stem removal is again attempted. If unsuccessful, the episiotomy can easily be converted to an extended trochanteric osteotomy from anterior to posterior (Fig. 102.8). During dislocation the assistant holds the extremity in flexion, adduction, and external rotation. A sterile anterior pocket attached during draping can be used, or, as we prefer, multiple sterile stockinettes can be placed on the operative extremity and removed when the patient’s extremity is brought back onto the operating table.

Exposure of the acetabulum is facilitated by placement of the extremity on the table in slight flexion and external rotation. Two Hohmann retractors are utilized: one placed anteriorly, and a second driven into the ischium to posteriorly retract the femur (Fig. 102.9). The entire gluteus medius and minimus complex can be elevated subperiosteally off the wing of the ilium from anterior to posteriorly depending on the extent of visualization of the acetabulum required, and thus preventing damage to the superior gluteal nerve. The use of a Charnley spike or Hohmann-type retractor driven into the ilium can provide retraction of the abductors and soft tissue.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree