The Direct Anterior Approach to Revision Total Hip Arthroplasty

Benjamin M. Frye

Keith R. Berend

Case

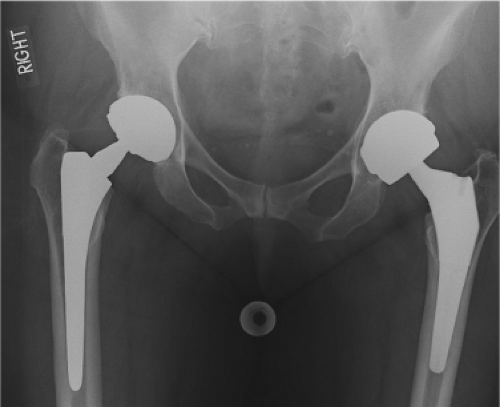

A 64-year-old female presented with severe left groin pain and sensations of catching and popping in her hip. She underwent primary left total hip arthroplasty (THA) 3 years prior to presentation. Examination revealed an antalgic gait and groin pain with hip motion. Radiographs revealed a THA with a large diameter metal-on-metal articulation (Fig. 106.1). Component size, position, and fixation appeared satisfactory. Laboratory evaluation for infection was negative, however serum cobalt and chromium levels were elevated and a fluid mass was found on ultrasound. The diagnosis of failed metal-on-metal THA with adverse local tissue reaction was made and the patient agreed to revision arthroplasty.

Introduction

The optimal surgical approach for revision THA depends on multiple factors. Adequate exposure is needed for implant removal and replacement, as well as management of anticipated bone defects. This often requires an extensile approach to access both the joint and bone–implant interfaces and must allow the surgeon the ability to deal with unanticipated intraoperative complications including periprosthetic fracture. Regardless of the approach chosen, the primary goals for revision THA must secure initial and long-term implant fixation and accurate component placement to provide a stable hip joint to protect against dislocation. Instability is a known complication of revision hip arthroplasty, with dislocation rates that are three to five times higher than that of primary THA (1,2) and hence optimizing stability is of paramount importance in revision THA.

The direct anterior approach is an internervous and intermuscular approach to the hip, which can be utilized for both primary and revision THAs. This soft tissue–sparing interval offers a versatile approach for primary THA and certain revision situations and can be extended both proximally and distally in the revision setting for more complex reconstruction. The direct anterior approach allows for complete preservation of the posterior hip structures for added postoperative stability and may also better allow the surgeon to assess leg length intraoperatively.

Indications

The standard direct anterior approach can be utilized for all isolated head and liner exchanges for polyethylene wear; this approach is particularly advantageous for this scenario given the high rate of reported instability when performed through a posterior approach. Nearly all isolated acetabular component revisions may be performed through this approach. In skilled and experienced hands, the exposure can be extended proximally for access to the ilium for more complex acetabular reconstructions. Distal extension can be performed for removal of a well-fixed stem or cement

mantle, placement of a long-stem revision component, or treatment of a periprosthetic fracture.

mantle, placement of a long-stem revision component, or treatment of a periprosthetic fracture.

Contraindications

Contraindications to this approach for revision THA will vary depending on the required access needed for the failed THA and the experience and comfort of the surgeon with performing the extensile portions of the approach. The proximal extension of the approach is similar to the Smith-Peterson approach (3), which gives access to the anterior column, outer and inner tables of the ilium but limited exposure to the posterior column and quadralateral surface of the acetabulum. Cases that require extensive exposure of the posterior column and ischium (such as a pelvic discontinuity) may be better suited with a posterior approach.

The distal extension of the approach allows complete access to the femoral shaft but requires either subperiosteal elevation or splitting of the vastus lateralis. Cases that require extensive exposure of the femur may be better suited with an extended posterior or direct lateral approach. Trochanter fracture can be encountered during the anterior approach, most commonly avulsion of the posterior capsule and external rotators during femoral exposure. Retractor placement over the tip of the trochanter may also predispose to fracture. Revision cases with extensive proximal femoral osteolysis will have an increased risk of trochanteric fracture and nonunion and may benefit from a different approach. Diaphyseal engaging stems are more difficult to insert through this approach due to limited femoral exposure. Cases which have proximal femoral bone loss or varus or retrotorsional remodeling will often require extended osteotomies and modular diaphyseal engaging stems. These situations may be better approached with posterior or direct lateral techniques.

Failed metal-on-metal THAs have been associated with adverse local tissue reactions and sometimes extensive tissue necrosis and pseudotumor (4,5,6). Revision cases for failed metal-on-metal components need to be carefully evaluated for evidence of large pseudotumors or tissue necrosis on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Large areas of tissue necrosis, especially in the abductor complex that will require debridement and possible soft tissue augmentation are better addressed through a lateral approach.

Surgical Technique

Isolated Acetabular Component Revision

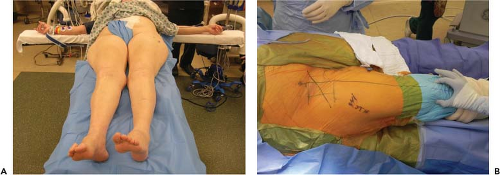

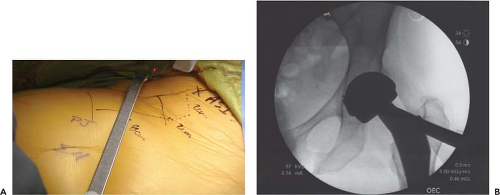

The direct anterior approach may be performed using a standard or special orthopedic traction table. The authors’ preferred method is the patient lying supine on a general use table with the pubic symphysis centered over the table break for hip extension when required. Both legs are prepped and draped to allow for assessment of leg lengths. The operative leg is draped from above the iliac crest to the ipsilateral knee to allow for complete extensile exposure (Fig. 106.2).

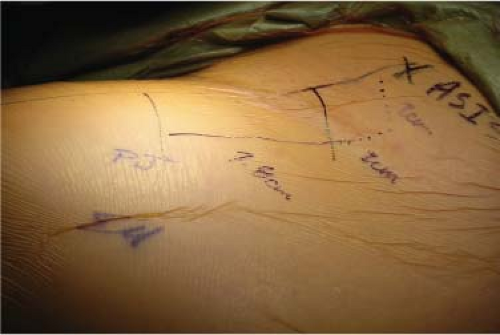

The authors’ standard length incision is approximately 6 to 10 cm in length and begins at a point two fingerbreadths distal and two fingerbreadths lateral to the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to avoid injury to the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve (Fig. 106.3). The location of the incision is confirmed with fluoroscopy to ensure that it is centered over the superior aspect of the femoral neck (Fig. 106.4). The incision begins through skin and subcutaneous fat until the overlying translucent fascia of the tensor fascia lata is seen. This fascia is then split in line with the incision and the muscle belly is bluntly dissected free from its superficial fascia and the fascia lying between it and the sartorius muscle. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve typically runs over the sartorius and is protected by dissecting lateral to this and within the tensor muscle sheath.

The deep fascia of the tensor fascia lata is then split exposing the lateral circumflex vessels. These vessels must be carefully cauterized and transected. Completely dividing the deep fascia of the tensor proximally and distally helps to retract the muscle laterally. Cobra-type retractors are placed between the femoral neck and the gluteus minimus muscle superiorly and the rectus femoris inferiorly exposing the hip capsule. A sharp, pointed retractor is used to peel

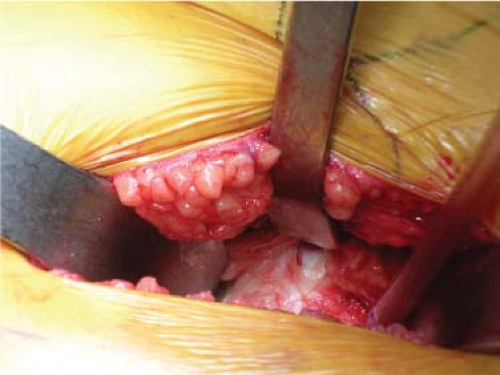

the reflected head of the rectus femoris from the anterior hip capsule and is placed over the anterior rim of the acetabulum (Fig. 106.5).

the reflected head of the rectus femoris from the anterior hip capsule and is placed over the anterior rim of the acetabulum (Fig. 106.5).

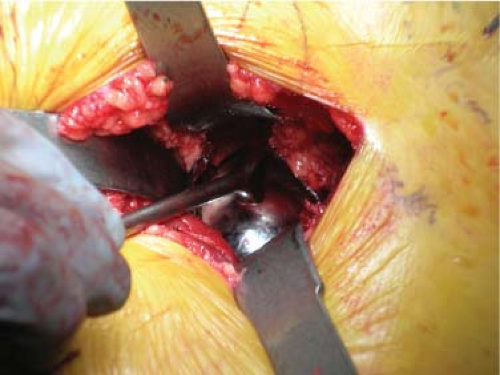

A complete anterior capsulectomy is performed to expose the prosthetic hip joint (Fig. 106.6). The anterior capsule or pseudocapsule can be thicker than that encountered during primary hip arthroplasty, especially if an anterolateral approach was used for the index procedure. A meticulous capsular resection allows for improved displacement of the femur and exposure of the acetabular component. Inferomedial capsule can also be released from the proximal femur down to the lesser trochanter to aid in exposure. At this point the hip is dislocated and the femoral head, if modular, is removed (Fig. 106.7).

A cobra retractor is repositioned over the anterior rim of the acetabulum to retract the rectus femoris, sartorius, and skin. A second cobra retractor is placed on the lateral aspect of the ilium proximal to the acetabulum to retract the tensor fascia lata and the abductors. A third retractor is placed over the posterior rim of the acetabulum toward the ischium to displace the femoral component. External rotation and slight hip flexion may help relax the rectus femoris and aid in posterior retraction of the femur. Any remaining pseudocapsule is now excised to provide full exposure to the acetabular component (Fig. 106.8). The existing polyethylene liner or hard bearing liner is removed with device specific extractors or other techniques.

Figure 106.4. A: Fluoroscopic verification of incision placement. B: Incision should be centered over the femoral neck. |

Acetabular component stability can now be assessed by removing any screws and impacting the rim of the component with a bone tamp or by using the specific manufacturer’s threaded inserter (Fig. 106.9). The surgeon may then proceed with liner exchange if the cup is stable and appropriately positioned, or with acetabular component revision if indicated. Curved chisels or explantation devices can be used for the removal of a well-fixed cup. Preparation of the host bone with acetabular reamers is performed in standard fashion with fluoroscopic assistance if required. A variety of revision acetabular components can be used and screws are easily placed through this approach. Fluoroscopy can be used to verify both cup position and screw placement.

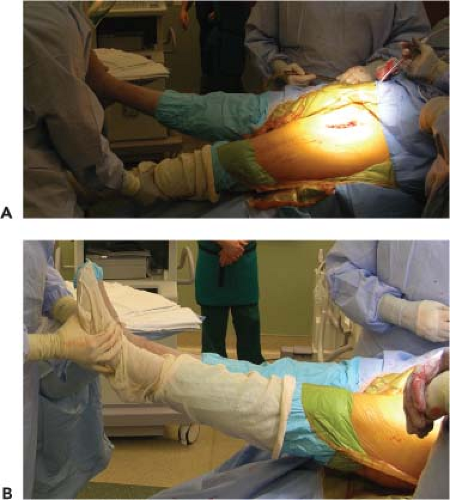

The polyethylene liner and trial femoral head are now placed and hip stability and leg lengths are assessed (Fig. 106.10). The advantage of the general use table as opposed to the orthopedic traction table is the ability to assess clinical leg lengths at the time of surgery. Fluoroscopy can also be used to assess length at the level of the lesser trochanters. Once stability and length are appropriate, final components are placed and the hip is reduced (Fig. 106.11). The hip is now irrigated, a deep drain is placed, and the fascia overlying the tensor fascia lata is closed in standard fashion (Fig. 106.12). Since the approach is usually the first

anterior approach the patient has had, the surgeon is able to perform an aesthetic primary closure (Fig. 106.13).

anterior approach the patient has had, the surgeon is able to perform an aesthetic primary closure (Fig. 106.13).

Figure 106.10. Assessment of hip stability and leg length with trial components. A: Anterior stability. B: Leg length. |

Figure 106.11. Final revision component. A: Large diameter DUAL MOBILITY articulation. B: Fluoroscopic image.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|