The Cup Cage Construct for Acetabular Revision

Louis S. Stryker

David G. Lewallen

Introduction

Despite advances in techniques, components, and bearing surfaces, the incidence of revision total hip arthroplasty is increasing with an anticipated growth of 137% in the revision burden between 2005 and 2030 (29,33). This is due to expected increases in the number of primary total hip arthroplasties in an aging population, as well as expanding indications for arthroplasty in ever younger and more active patients. Reasons for revision are varied and often multifactorial. The three most common diagnoses identified by ICD-9-CM procedure codes are instability/dislocation (22.5%), mechanical loosening (19.7%), and infection (14.8%) (7). In the same study, 53.8% of all procedures involved acetabular component revision, either in isolation (12.7%), or as part of an all component revision (41.1%). The need, therefore, to provide consistent and durable solutions to acetabular reconstruction at the time of revision surgery is clear. Further delineating this need is the significantly increased incidence of complications, including infection and instability, in patients requiring multiple revisions (28).

The location and extent of compromised acetabular bone stock encountered during revision surgery varies and is based on the etiology. Common causes include removal of previous bone to accommodate the initial prosthesis, implant-related osteolysis, and motion of loose components.

Just as a spectrum of defects can be seen, they can be addressed in a variety of ways. Uncemented hemispherical porous acetabular components were the early solution following relatively disappointing outcomes using cemented revision components (34,52). The success of uncemented revision components, however, is dependent on the quality and structural integrity of host bone which allows for rigid initial fixation and sufficient host bone surface for ingrowth. When existing acetabular bone stock did not meet these conditions, failure rates were unacceptably high (14,24,25,31,35). At the same time, mid-term results of conventional cage constructs began to be reported and there was an associated increase in their use for revision surgery (4,44). Other techniques for treating large areas of acetabular bone loss have also been described and reported in the literature. These include custom triflange components, bipolar prostheses, and bilobed prostheses, although the latter two have largely been abandoned due to poor outcomes as well as the development of newer techniques, whereas the former continues to be investigated.

Benefits of the cage construct include restoration of the anatomic joint center and rigid component support, as well as the ability to span large defects, support large areas of cancellous and bulk structural allograft, and distribute forces over relatively large areas (2). The success rates of conventional cage constructs reported in the literature have varied widely, likely due to differences in selection criteria as well as surgical technique. Short- and mid-term survival rates have ranged from 63% to 100% (4,20,40,44, Garbuz, Morsi et al. 1996,3,6,8,15,16,39,41,47,50,54,56). Similarly, longer-term follow-up has shown varied outcomes with a worst case Kaplan–Meier survival curve of 61.75% at 14 years to no revisions for aseptic loosening reported at a mean of 10 years (5,42,43,46,51,55,57).

The disadvantages of the conventional cage construct include the requirement of a large exposure and that they can be technically difficult to implant. The most concerning limitation is the lack of an ingrowth surface which makes these contructs susceptible to late fatigue failure (4,16,18,38).

The development of trabecular metal components and augments, and the promise of long-term biologic fixation, has partially supplanted cage constructs in the management of some defects. Excellent short-term results have been reported in the literature, and in some instances were used in defects that would previously have been treated with conventional cage constructs (22,32,36,48,49).

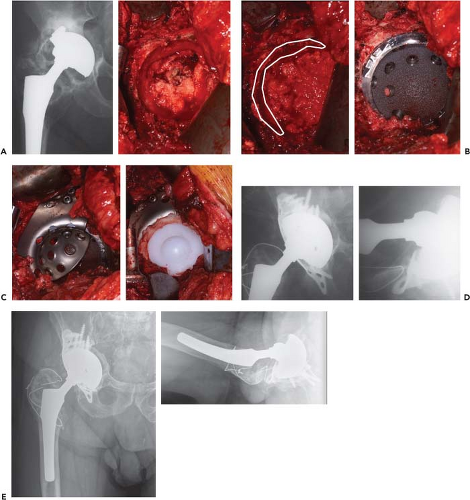

Some instances remain however where these contructs lack the necessary immediate support for biologic ingrowth and long-term fixation. One solution to these massive defects is the cup-cage construct which combines a porous ingrowth acetabular component and a cage placed over the top (see Fig. 114.1). With this synergistic combined method each technique’s strength is used to compliment the other’s main weakness, with the rigid early fixation of the cage allowing for the long-term biologic fixation into the highly porous metal cup which then reduces stresses on the screws and flanges of the cage over time (17,19,22,32).

Indications

The cup-cage construct is well suited to defects which preclude rigid fixation and durable stability using a porous hemispherical cup, with or without the use of augments. These include large combined deficiencies as well as pelvic discontinuities. A multitude of classification systems exist to describe these defects and potentially guide treatment (10,12,13,37,45). Cup cages should also be considered when significant osteolysis is noted about the ischium. Standard hemispherical revision components lacking adequate acetabular fixation in this location rock on the superolateral acetabulum and are predisposed to subsequent early failure. Previously, defects with awkward or irregular geometry would have also been an indication, however, with the variety and versatility of currently available augments this is now of less concern. Augments may also be used to compliment cup-cage constructs to restore the anatomic hip center and potentially improve long-term survivorship (27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree