CHAPTER 1 The concepts of osteopathic medicine

past and present

Introduction

At a recent research symposium dealing with synergistic goals in manual therapy research, the first author presented the set of osteopathic concepts as they related to research priorities (Langevin et al. 2009). During the panel discussion, presenters from the chiropractic, physical therapy, massage therapy and body worker professions all said that their respective professions taught similar concepts within their scope of practice. Therefore, this chapter reflects inclusiveness for all manual therapy professions as far as concepts are concerned while acknowledging the longer history of osteopathy and the emphasis placed on underlying concepts by the osteopathic medical profession. The authors of Chapters 13 Chiropractic, 14 Physical Therapy and 15 Massage Therapy present some elaboration on the concepts presented in this chapter as well as the background of their respective professions.

Indeed, the accumulated research accomplishments of manual therapy over the past 15 years have resulted in the inclusion of spinal manipulation into federal agency medical practice guidelines (Bigos et al. 1994). Osteopathic and manual therapy research has also contributed to the inclusion of diagnostic codes for somatic dysfunction (defined and discussed below) in the definitive reference source for medical diagnoses, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM, 2008) and procedure codes for osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) in Current Procedural Terminology (American Medical Association, 2009) both essential for the process of physician reimbursement for manual therapy services. Inclusion of these diagnostic and procedure codes in definitive reference books places osteopathic and manual therapy in the mainstream of modern medical practice.

Osteopathic medicine – background and comparison with allopathic medicine

‘Osteopathic medicine has from its beginnings been a profession based on ideas, tenets that have lasted through all sorts of adversity and have been credited with bringing the profession to its present level of success’ (Peterson 2003, p. 19). This set of concepts and their associated applications to medical practice originate with a 19th century itinerant, apprentice-trained American physician, Andrew Taylor Still, who served as a military physician on the side of the North in the American Civil War. After the deaths of three of his children from spinal meningitis, Still eschewed the common medical practices of the day such as purging, blistering and bloodletting in search of a better form of healthcare. In 1874, a personal experience in which he received relief from a headache by resting his neck over a sling of rope hung between two trees started still on the path of discovery of what he called osteopathy. From its very beginning the neuromusculoskeletal system evaluation and treatment has been central to the osteopathic profession. After years of successful practice of osteopathy, in 1892 he established the American School of Osteopathy.

Following the Flexner Report of 1910, which sought to standardize medical education and was responsible for the closure or merging of many medical schools (Flexner 1910), eight osteopathic medical schools survived the reforms in American medical training, as they were deemed by Flexner to have curricula sufficiently consistent with the new standards of the time. This was a very important event, as it set the stage for the development of osteopathic medicine as a distinct school of medicine coexistent with allopathic medicine. In America, the DO – Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree – and the MD – Doctor of Medicine – permit licensure for the ‘full scope of medical practice,’ and as such both degrees are equivalent in practice privileges.

The adversity that Peterson (2003) speaks of was due primarily to lack of understanding of, and resistance to, osteopathic concepts, which emphasized the evaluation and treatment of the musculoskeletal system in healthcare, in contrast to the modern allopathic profession (defined below), or ‘regular’ internal medicine, which emphasized a pharmacological approach. Stated another way, osteopathic concepts emphasize the use of the biological mechanisms of the brain/body in its treatment strategies, whereas traditional modern medicine has the tendency to influence them through the use of chemical agents as the first line of treatment. As for the practice of surgery, which technically is not considered allopathic medicine, both medical and osteopathic professions have been virtually identical since the 1940s. Since the 1960s osteopathic physicians have had full medical practice rights in all the states and in the military medical services.

Although there remains a lively debate on the primacy of allopathic pharmacologically based practices with regard to osteopathic musculoskeletal/anatomically based practices, in recent times the two professions have worked toward a rapprochement. This increased cooperation stems partly from the fact that osteopathic physicians meet a critical need for healthcare in the United States. Also, in the last decade, the publication of research on osteopathic manipulative medicine (Chapter 12), as well as the research on other manual therapies (Chapters 13–15) has increased acceptance of these practices in medical practice, as mentioned above.

Osteopathic medical philosophy

The modern version of osteopathic philosophy was published in 1953 (Special Committee on Osteopathic Principles and Osteopathic Technic, 1953) and has become known as the Four Tenets (Box 1.1). Because it relates to the theoretical underpinning of much of the research presented in this book, the elaboration of the Four Tenets published in 2003 (Seffinger et al. 2003, p. 5) is presented in Box 1.2. Still’s fundamental concepts of osteopathy can be organized in terms of health, disease, and patient care, which gives a statement of broader application of healthcare from the osteopathic perspective.

Disease

Osteopathic principles – heuristic implications and development

Somatovisceral and viscerosomatic interactions

The statement in Box 1.2, for emphasis, under #3 ‘Health,’ #5 ‘Disease,’ and #8 ‘Patient Care’ that ‘illness is often caused by mechanical impediments to normal flow of body fluids and nerve activity,’ has led to the development of specific OMT and manual therapy procedures to accomplish the reversal or elimination of mechanical impediments. As described briefly below and more extensively in Chapter 12, OMT has been shown effective in the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders. These finding stem from Still’s development of the concept of the removal of mechanical impediments by OMT for musculoskeletal disorders, such as pain, and can be considered the mechanical peripheral component of his theory. From Still’s writings it appears that simultaneously or very shortly thereafter he postulated the concept of viscerosomatic and somatovisceral interactions as an integration of peripheral (afferent and efferent) nervous system activity and central nervous system activity. This aspect of Still’s concepts has also led to research on nervous system functions such as viscerosomatic interactions and alterations of spinal reflex excitability.

The earliest osteopathic account of somatovisceral interaction is an anecdotal story reported by Still and later published in his autobiography. Still writes in detail of the treatment of a child with ‘bloody flux,’ as severe diarrhea was called in the 19th century. The OMT was to several sites on the child’s vertebral column that Still described as ‘warm to the touch,’ compared to the child’s ‘cold’ stomach. Still’s treatment apparently corrected the problem, bringing relief to the child and expressions of gratitude from the child’s mother (Still 1908, p. 104–106). Still later described the pathophysiology and treatment for this condition, and in so doing was among the first to connect musculoskeletal dysfunction with systemic disorders.

Citing the work of Claude Bernard in 1850 as impetus, Louisa Burns, an early osteopathic physician and researcher, published research in 1907 that influenced osteopathic thinking and research over the last century. Burns described experiments on cats and dogs demonstrating a viscerosomatic interaction: ‘For the experiments upon the abdominal viscera, the abdominal wall was cut, and the viscera exposed to view with as little manipulation as possible. The stimulation of the inner wall, the muscular coat and the peritoneal covering of the cardiac end of the stomach or of the fundus was followed by the contraction of the spinal muscles near the sixth to the ninth thoracic vertebrae’ (Burns 1907, p. 54). For a somatovisceral interaction, she stated: ‘The stimulation of the tissues near the fifth to the eighth thoracic vertebrae was followed by muscular and secretory activity in the stomach, and stimulation near the eighth to the twelfth thoracic vertebrae was followed by activity of the intestines.’ (Burns 1907, p. 55). In the same article she describes stimulation of the spine in humans that appeared to change blood pressure readings in 37 ‘healthy individuals.’

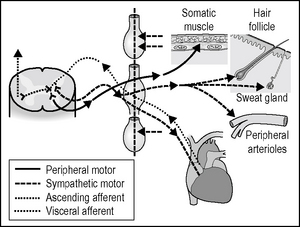

As is documented in this book (Chapters 2–4, 7–8, 10), the concept of somatovisceral and viscerosomatic interactions is a well-studied and useful concept in the neurosciences, most notably found in the work of Akio Sato (e.g., Sato & Schmidt 1971, Sato 1972), some of which is described in Chapter 2. Figure 1.1 is a schematic representation of the viscerosomatic reflex wherein a visceral dysfunction, due, for example, to an infection or other disease process, causes a reflex activation of some kind in somatic or musculoskeletal structures. The early work of Denslow and Korr (Denslow 1944, Denslow et al. 1947, Korr et al. 1962) established the scientific credibility for osteopathic treatment based on the concept of somatovisceral interactions and a related concept of the facilitated segment(s)/area.

Figure 1.1 Schematic representation of the viscerosomatic reflex.

From Beal M C 1985 Viscerosomatic reflexes: a review. Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 85:786–801, reprinted with permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree