CHAPTER 6 The basic exercises

General introduction: basic exercises

How to use the basic exercise section

In the section on yoga and health in Chapter 1, we emphasized finding and developing healthy structures in the body as a fundamental approach for therapeutic yoga. To learn how to use these structures in a sensible way to improve their function we have applied the principles of mindfulness, variety of exercise approaches, economical practice, precision, and finetuning to the exercise approach. Specific aims for improving bodily structure and function are mobility, strength, stamina, relaxation, balance, coordination, synchronization, and breathing naturally.

Our experience with patients’ motivation has shown (see also Chapter 4):

We have collected together this set of basic exercises as a tool for therapists, instructors, and patients. The exercises are divided according to the areas of the body. This is not a strict division; rather it is a focus. Some exercises are similar for different areas, focusing on different areas, sensations, or movements. A different emphasis or applying a prop in a different way brings the focus to another area. For example, in supported forward bending, placing a rolled blanket underneath the lower abdomen targets the lumbar spine (exercise 1.7, Figure 6.13), whereas placing the rolled blanket underneath the costal arches targets the dorsolumbar junction and the lower ribs (exercise 2.7, Figure 6.49). For each area there are exercises emphasizing one or more aims. These aims are stated at the start of the exercise. In each and every exercise you should aim for a good quality of breathing. The rib exercises are particularly helpful to improve breathing.

These basic exercises are modified from more complex yoga āsanas or their preparation. Most of these basic exercises are teaching details of āsanas and help us to understand fine adjustments of the āsanas. Even if the exercises are small and subtle it is important to integrate them into a good all-over posture while working with the whole body in a sensible way. An important example is to maintain a stable position of the pelvis and keep the spine lifted while practicing exercises for the thorax, shoulders, cervical spine, or head. Therefore these basic exercises are yoga exercises, too, particularly as we put a great deal of emphasis on applying the principles of mindfulness, variety of exercise approaches, economical practice, precision, and finetuning during exercising. All the principles are relevant for all exercises, and should be applied during practice. Mindfulness is paramount among the principles (see Chapter 2) and particularly connects to the spirit of yoga. It underlies all the other principles: variety, economical practice, precision, and finetuning.

The exercises are not meant to be carried out one by one as presented here. They can be selected and combined for each patient according to the diagnosis. The sequences should gradually increase in intensity and finish with a quiet exercise or Śavāsana (see Chapter 7). Some of the basic exercises have several variations. This was designed to cater for the great variety of anatomical shapes and movement possibilities, to meet individual needs.

As emphasized in Chapter 3, it is essential to carry out a thorough case history and examination, including contraindications in certain conditions. Keeping in mind your patient’s particular aims and selecting and applying the exercises accordingly, this approach can be applied to many conditions. In particular it is useful to help target restricted areas and protect hypermobile ones, which is fundamental in many musculoskeletal problems. Patients who have many symptoms will probably already have had a lot of therapy. Do not add more; rather start the patient on exercises he can still do to encourage him. Other exercises can gradually be added to help the body correct itself and improve the patient’s chance of self-healing.

The recommended timings and number of repetitions are based on long-term observations, what feels right for many patients, and on research results (Pullig Schatz 1992, Tanzberger et al 2004, Lederman 2005). However, the results vary within a range of possibilities: again, careful observation and mindful exercising will be a helpful guide. Frequently used timing for holding stretches or strengthening is 3–5 breaths, for repetitions of basic exercises 3–5 times. Unless directed otherwise, by breath we mean one inhalation and one exhalation. For beginners the time may be shorter, gradually increasing with practice. Within a sensible range it also depends on the desired effect. The lengthening of a muscle in a relaxed position may take much longer, depending on the individual situation. It usually takes several minutes to get into deep relaxation. So it is important that the therapist and the patient are clear about the aims of the exercises and understand the principles.

Exercises should not be held so long or repeated so often that the patient becomes exhausted or uncomfortable. Ask patients how they feel, and then adjust the intensity, timing, and way of performing the exercises according to the feedback. If a stretch is painful, modify the challenge so that it becomes tolerable. After exercising patients should feel comfortable. If they feel continuing pain after exercising, they should be referred for medical investigation (see Chapter 3). If the results are negative, check again that the patient is carrying out the exercises correctly, and perhaps make the practice shorter or less intense.

In summary the basic exercises are modified from classical āsanas:

Frequently used positions and movements

For the position of the feet we sometimes use dorsiflexion and plantar flexion (exercise 10.3, Figure 6.194). Dorsiflexion is the movement at the ankle towards the superior surface of the foot. When wearing flat shoes the foot is mainly in dorsiflexion. Plantar flexion is the movement at the ankle towards the sole of the foot: the higher the heels, the more the foot is in plantar flexion. In dorsiflexion the foot has more stability, whereas in plantar flexion it its more vulnerable. Inversion is the movement of the foot inwards (exercise 10.3, Figure 6.195), while eversion is an outwards movement (Figure 6.196), both without rotation at the hip or knee joints (Kingston 2001).

Supination and pronation in the elbow joint are the rotation of the radius on the ulna. Supination is the rotation of the forearm so that the palm is facing forwards, with the thumb outwards, whereas pronation is the rotation of the forearm so that the palm is facing backwards, with the thumb inwards. The joint surfaces of the carpal bones also allow some complex supination and pronation movements (Kingston 2001).

The neutral position is a fundamental position for many exercises. “Lumbar neutral position is midway between full flexion and full extension as brought about by posterior and anterior tilting of the pelvis … the neutral position places minimal stress on the body tissues. Also, because postural alignment is optimal, the neutral position is generally the most effective position from which trunk muscles can work” (Norris 2000, p. 10). In this neutral position the joints and their soft tissues are least stressed. The neutral position must be distinguished from the concept of neutral zone. This is “the zone in which movement occurs at the beginning of the range of motion before any effective resistance is offered from either the muscular system or the spinal column” (Norris 2000, p. 9). The less stable a spinal segment is, the larger the neutral zone.

Supine means lying on your back. To achieve the optimum neutral, relaxed position you may need support. To support from the bottom, place a rolled blanket or bolster underneath the knees or a chair under the lower legs. To support from the top, put a pillow underneath the neck and head (see Śavāsana, Chapter 7). There are various methods to support lying supine (Lasater 1995). You may need to experiment to find the best for individual patients. To come up from the supine position, stretch your right arm over your head and turn on your right side, with the right arm supporting the head. Bend both knees, keeping your left hand on the floor in front. Stay lying comfortably on this side for a few breaths in a neutral lumbopelvic position. To push yourself up to sitting, set your left leg slightly free from the bent position. If you prefer to finish on the left side, turn onto your left side in the same way. Moshe Feldenkrais has written a very detailed description of this and other transitions between different positions (Feldenkrais 1984).

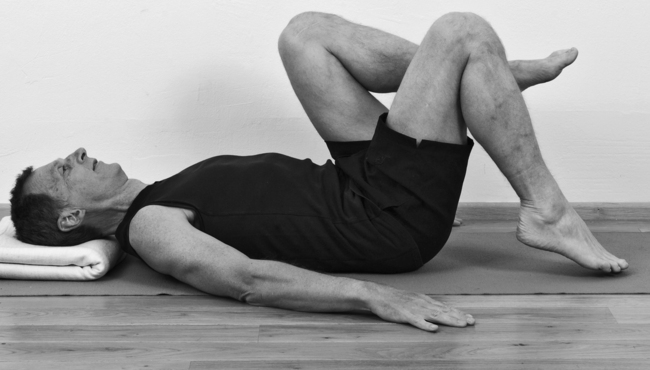

The knee hug position (exercise 1.4, Figure 6.4) is the starting and finishing position for lumbar mobilizing and abdominal strengthening exercises. It is a relaxing pose on its own.

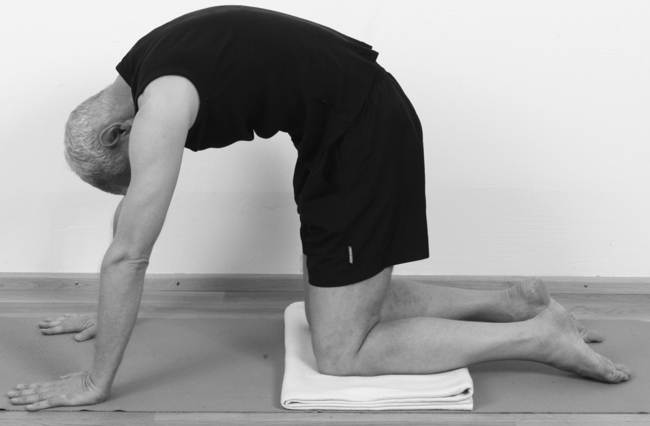

Four-point kneeling (exercise 1.14, Figure 6.28) and variations is used in several chapters, with different emphasis. Patients may find it comfortable to kneel on a soft support like a folded blanket. This also increases the height of the pelvis so that the back is closer to the horizontal line.

Forward-bent kneeling (exercise 1.9, Figure 6.16) is a suitable position to finish four-point kneeling variations as well as the dog pose. It is a relaxing pose on its own, particularly if performed with props, as shown in exercise 1.9 (Figure 6.16). In addition to the supported relaxation poses we have given a few examples of oscillations. These gentle rhythmic movements are particularly inspiring fluid movements (Lederman 2001). To refine the exercises and sink into deeper relaxation it is important to feel softness in the eyes, ears, palate, tongue, and larynx, and to be receptive and mindful during practice (see Chapter 2).

Many of the exercises get easier and more accessible by using props. The questions of what patients can do and which exercises should be avoided are replaced by the question of how to modify the exercises. We describe important basics for this exercise approach, as this is an important factor in therapeutic exercising. Most of the props we suggest can be found at home. We recommend buying a sticky mat, a foam brick, and a belt (see Chapter 1).

1 Basic exercises for the lumbar spine

Exercise 1.1 Lumbopelvic stability

Aims: strengthening the lower abdomen, pelvic floor, and lumbar area.

Exercise 1.2 Abdominal strength

Aims: gentle strengthening of the abdominal muscles, stabilizing the lumbar spine.

Stronger variations

Variation a

Variation b

Lie on your back with your hips and knees bent; hold the knees close towards the chest so that the back rests comfortably on the floor (Figure 6.1). Maintain this contact of the pelvis with the floor throughout the exercise. Practice as described in variation a, except that you move the legs in three sections while lifting them off the floor.

Variation d

Exercise 1.3 Rhythmic relaxation

Aim: gentle mobilization of the lumbar spine.

Exercise 1.4 Knee hug rotation variation

Aims: mobilizing the lumbar spine into rotation, balancing the trunk muscles.

Exercise 1.5 Knee hug side-bending variation

Aims: mobilizing the lumbar spine into side-bending, balancing the trunk muscles.

Exercise 1.6 Roll the back

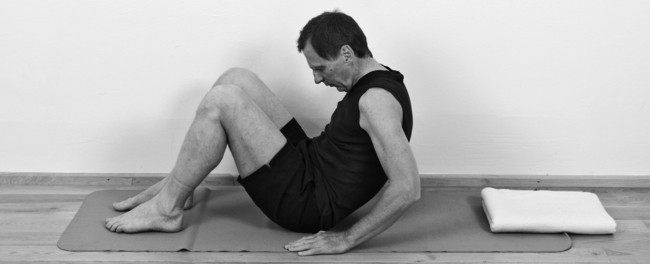

Aims: mobilizing the lumbar spine into flexion, strengthening the front aspects.

Refined work

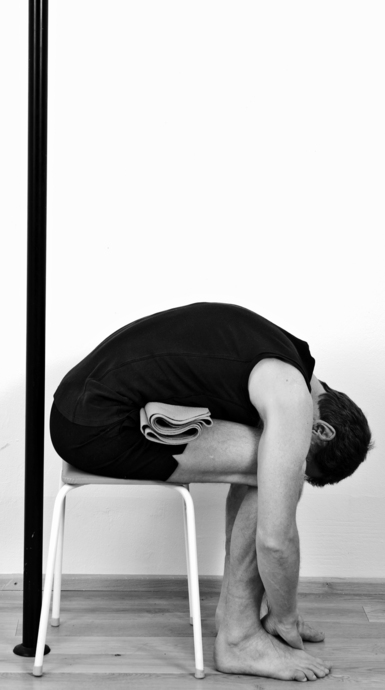

Exercise 1.7 Roll the back on a chair

Aim: mobilizing the lumbar spine into flexion.

Exercise 1.8 Coachman relaxation

Aim: relaxing the lumbar spine.

Variation

Exercise 1.9 Arched and hollow back with side-bending

Aims: mobilizing the lumbar spine, coordination.

Preparation: arched and hollow back

Refined work: arched back and hollowing with side-bending

Exercise 1.10 Side-bending strength

Aims: mobilizing the lumbar spine into side-bending, strengthening the lumbar spine, balance.

Refined work, particularly emphasizing balance

Exercise 1.11 Balance on the side

Aims: strengthening the lumbar spine, balance.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree