Chapter 8 The Back

Back pain is one of the most frequent conditions requiring medical treatment. It is also the most expensive ailment for patients between the ages of 30 and 60 years and one of the most difficult to treat. Back pain may be caused by a variety of disorders, including gynecologic, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal diseases, but the most common causes are disorders of the lumbar disc.

Anatomy

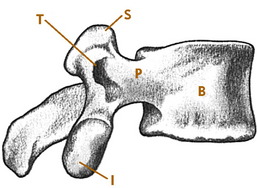

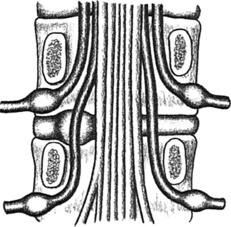

The vertebrae, discs, and ligaments of the dorsal and lumbar spine are similar in most respects to their counterparts in the cervical spine. The lumbar vertebrae are larger and thicker, however, because of their weight-bearing function (Fig. 8-1). Anterior and posterior longitudinal ligaments are applied to the respective surfaces of the vertebral bodies, and posterior stability is aided by supraspinous and interspinous ligaments and the ligamentum flavum. The discs account for more than one third of the total height of the lumbar spine and account for most of the normal lordosis.

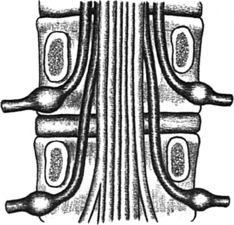

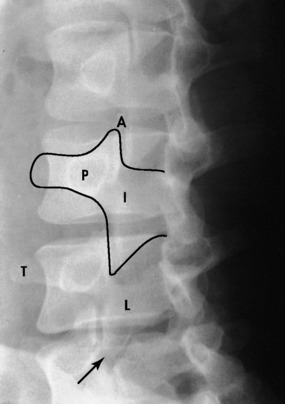

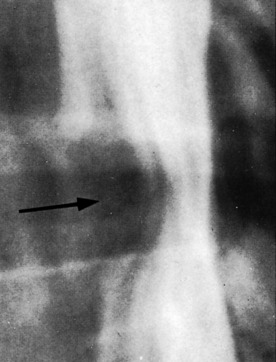

Spinal nerves exit the canal by passing through intervertebral foramina; each foramen consists of the inferior aspect of the pedicle above and the superior aspect of the pedicle below the level of exit. In the lumbar spine, disc disease usually affects the nerve root exiting one level below, because that is the nerve that actually passes over the disc (Fig. 8-2). Thus, a herniated disc between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae commonly affects the fifth nerve root and not the fourth.

History

The evaluation of the patient with back pain should first begin with the obvious questions regarding the common causes of spine disorders (trauma, disc disease, degenerative disorders, etc.). However, because low back discomfort can develop in conjunction with a variety of diseases not considered orthopedic in nature, this initial assessment should also include information developed about general medical disorders that could be causally connected with the spine complaints. This is especially true if the symptoms appear atypical (pain radiating into the groin, testicle, vulva, or inner thigh). If this cannot be done on the initial visit because of limited time, it eventually must be done if the patient’s condition does not improve and the patient returns with the same complaints.

A few simple questions should be sufficient for general system review as follow:

The smoking history is always critical. In addition, certain “red flags” should signal the possibility of a more serious condition underlying the low back complaints (Table 8-1).

| Fever, malaise |

| History of malignancy |

| Night pain or pain at rest (suggests spinal malignancy) |

| Incontinence, perianal sensory loss |

| Weight loss of unknown origin |

| Loss of strength, balance |

| Sudden worsening of pain level |

| History of substance abuse or issues of secondary gain |

| Night sweats |

| Significant morning stiffness |

Examination

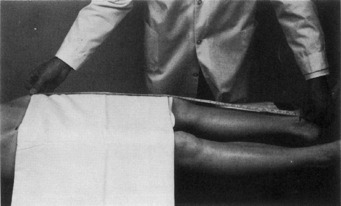

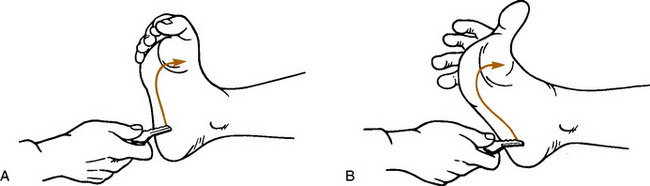

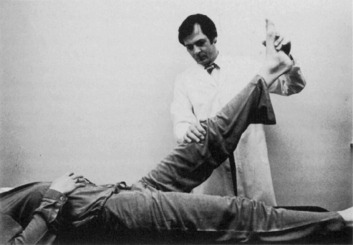

With the patient in the supine position, the hip is placed through a full range of motion and thoroughly tested to rule out primary hip abnormality. The straight-leg–raising tests are then performed, and the leg lengths are measured (Fig. 8-3). Next, with the patient on the side, manual pressure is applied to the iliac crest (pelvic compression test). Reproduction of pain in the sacroiliac joints or symphysis pubis with this maneuver may suggest disorders of these areas. The presence or absence of clonus can be determined at this time, and Babinski testing can be performed (Fig. 8-4).

Roentgenographic Anatomy

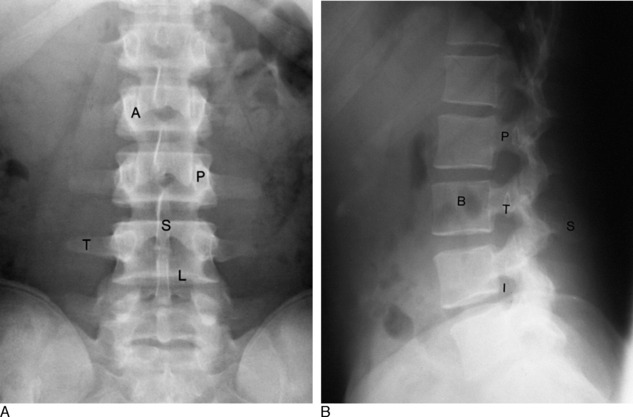

An evaluation of disorders of the lumbar spine should include a standard roentgenographic examination. The roentgenographic features are well visualized by the following: anteroposterior view (Fig. 8-5, A), lateral view (Fig. 8-5, B), and oblique views in both directions (Fig. 8-6). In addition, a spot lateral view of the lumbosacral space may be necessary.

Lumbar Disc Syndromes

The intervertebral disc is probably the major source of most back pain, and the pattern of disc deterioration in the lumbar spine is similar to what occurs in the cervical spine. The majority (95%) of disc lesions in the lumbar spine occur at the fourth and fifth spaces, with most of the remainder occurring at the third space. With normal aging, biochemical and mechanical changes occur in the nucleus pulposus. Eventually, disc material may begin to protrude or even herniate into the neural canal. This most often occurs in the area of greatest weakness of the anulus fibrosus at the posterolateral aspect of the disc (Fig. 8-7). Herniation is most common in the third and fourth decades and is rare before the age of 15. Chronic disc deterioration (spondylosis) may also develop over time and result in osteophyte formation, disc space narrowing, and degenerative changes in the facet joints and between adjacent vertebral bodies. (NOTE: In addition to mechanical causes, chemical and inflammatory factors may also play some role in the development of back pain. Although the mechanical causes may be the easiest to visually understand, a precise diagnosis as to the etiology of back pain in many patients simply cannot be established with any certainty.)

FIG. 8-7 Lumbar disc protrusion. Note that the herniation affects the root that exits one level below.

A rare but serious complication of lumbar disc disease is the cauda equina syndrome. This results from a massive central disc herniation and may produce variable degrees of permanent paralysis in the lower extremities. Bladder and bowel function may also be severely impaired. This condition is a true emergency and usually demands immediate evaluation and surgery.

CLINICAL FEATURES

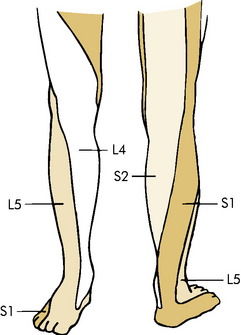

Paresthesias in the form of numbness and tingling are common and are usually more marked in the distal portion of the extremity. They may follow a specific dermatome pattern (Fig. 8-8).

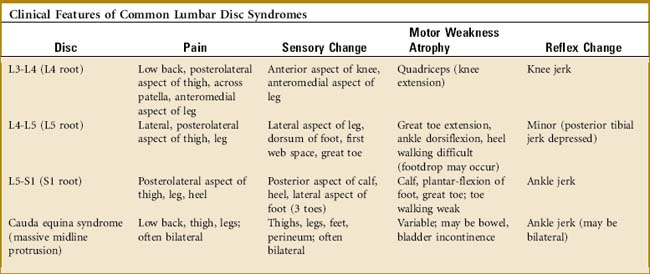

Examination often reveals restriction of low back motion. Bending toward the affected side frequently exacerbates the pain. Variable degrees of local tenderness and muscle guarding are present. In an attempt to relieve pressure or tension on the nerve root, the patient may list or bend away from the painful side and stand with the affected hip and knee slightly flexed. A characteristic clinical picture may be present, depending on the level of nerve root involvement (Table 8-2). The sensory examination may reveal diminished sensation along the affected dermatome, although the sensory examination is usually not very helpful. The various tests measuring sciatic nerve root tension are frequently positive if herniation is causing nerve compression (Fig. 8-9).

SPECIAL STUDIES

NOTE: The number of symptomatic conditions discovered by special studies but not suspected clinically is very small. Tests such as MRI and EMG should only be performed as adjuncts to the clinical assessment.

TREATMENT

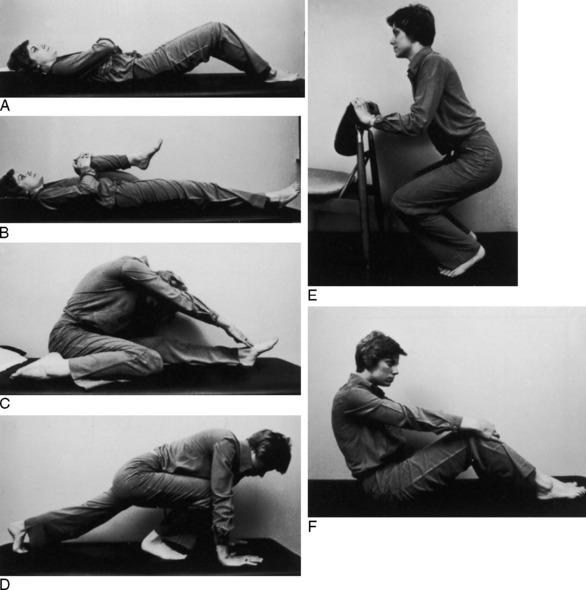

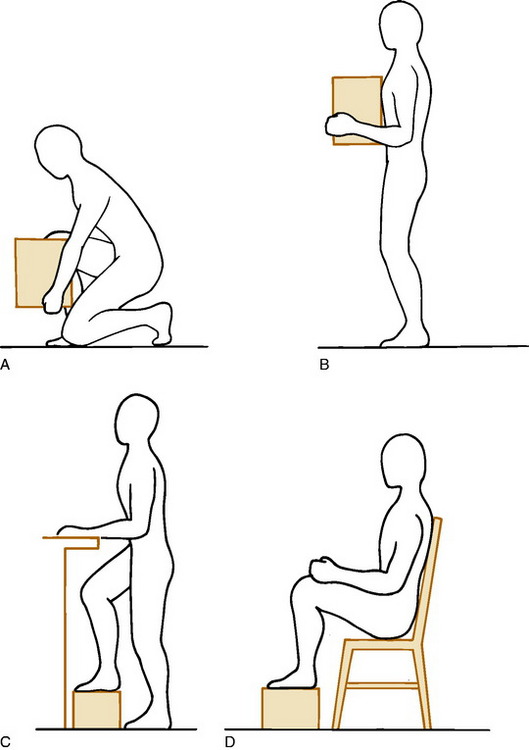

The initial treatment is always conservative, and the majority of patients respond well. Treatment is based on the symptoms of the patient and not on any imaging study. Extended periods of inactivity are no longer recommended for most low back disorders, but a short period of bed rest (5 to 10 days) may be very helpful in the treatment of acute disc herniation, mainly if radicular leg pain caused by nerve root compression is present. This is followed by a careful exercise program. While the patient is in bed, the hips and knees are kept moderately flexed. Lying on the abdomen, which increases the lumbar lordosis, is avoided. Hip flexion and pelvic tilt exercises are begun within the limits of pain (Fig. 8-11). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), analgesics, and moist heat are used as necessary. Narcotics may even be required in cases of nerve root compression and intense leg pain. If improvement occurs, which it does in the majority of cases, gradual resumption of activity is allowed, and the exercise program is expanded. Physical therapy is often useful, mainly for the exercise program. Modalities such as deep heat and massage can be added for their “hands-on” appeal. A lumbosacral corset may be temporarily used. (There is no evidence that continued use of any brace promotes back weakness, however, especially if the patient adheres to an exercise program.) Recurrences are prevented by a proper exercise program and the avoidance of stress to the lower part of the back (Fig. 8-12).

SUMMARY

CHRONIC LUMBAR DISC DISEASE

A high percentage of adults older than 40 years of age have degenerative disc disease at one or more levels on roentgenographic examination (Fig. 8-13). Significant thinning of the disc accompanied by osteophyte formation is often present. And MRI studies commonly reveal “bulging” disc abnormalities in patients, many of whom are without symptoms. These roentgenographic changes are common in the general population and are present in 30% to 40% of normal individuals. They are so common, in fact, that some question whether or not lumbar disc disease should be considered a “disease” or simply a change which occurs with age. Disc degeneration and the accompanying changes in the adjacent facet joints with soft tissue inflammation can, however, lead to intermittent low back pain and even nerve root irritation or compression with leg pain. The severity of the symptoms often bears no relation to the severity of the radiographic findings, however.

Pain of this nature usually responds to conservative management. NSAIDs, analgesics, rest, moist heat, and the use of a lumbosacral corset may be the only treatment necessary. Exercises, education, and postural training are important. Risk factors associated with chronic back pain should be addressed, such as smoking and poor physical conditioning. A physical therapist can be helpful in this regard. When signs of nerve root irritation with radicular pain are present, compression or irritation of the root by a small, acute, soft disc herniation or degenerative osteophyte should be suspected. The leg pain often responds well to epidural pain blocks. Surgical intervention is occasionally indicated to relieve nerve pressure. Arthrodesis of the adjacent vertebrae may rarely be indicated to relieve chronic low back pain by stabilizing the degenerated painful disc segment but the procedure is highly controversial (see Chapter 18). Conservative treatment is usually successful in most cases. Recurrences are not uncommon and generally respond to medical management.

LUMBAR SPINE STENOSIS

CLINICAL FEATURES

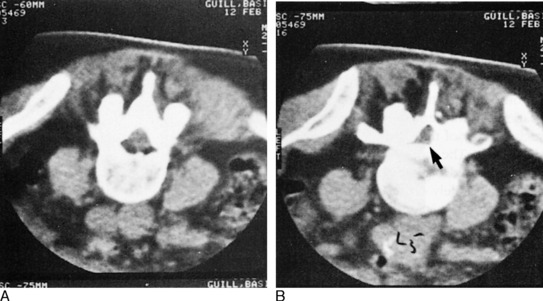

Roentgenographic examination of the lumbar spine usually reveals degenerative changes throughout the lower part of the back. EMG and myelography may help localize the disorder, and CT scanning is frequently diagnostic (Fig. 8-14). MRI is also helpful.

THE FACET SYNDROME

The small articular facet joints of the spine have occasionally been implicated as a cause of chronic low back pain. They may become affected secondary to disc thinning and frequently develop arthritis. And even though arthropathy is a common finding in these joints, the relationship of this abnormality to back pain has been difficult to prove. As a result, many doubt the existence of this disorder. The patient is often one who has a long history of chronic spine pain that has not responded to the traditional methods of management. Clinically, there may be local facet tenderness and pain on side bending. To alleviate the symptoms, injection and even denervation of these joints have occasionally been performed. The results of these treatments are only modestly successful.

Lumbar Strain

With a daily program of proper postural exercises, weight loss, and a general exercise program, most patients who develop chronic back pain will be able to rehabilitate the lower part of the back. The use of modalities (hot packs, massage, etc.) in physical therapy is discouraged, although short-term use may allow the exercise program to be more easily implemented. Full cooperation is necessary.

Isthmic Spondylolisthesis

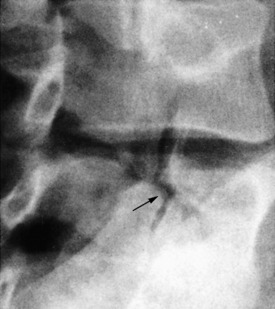

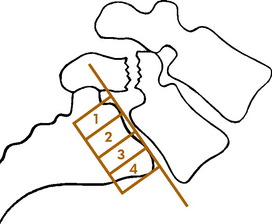

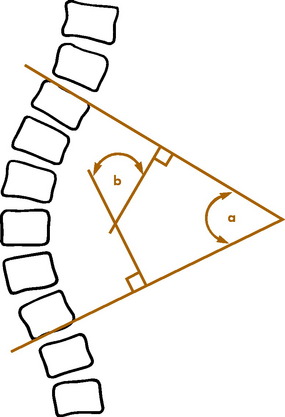

Spondylolisthesis is a disorder, usually in the lumbar spine, in which one vertebra gradually slips on another. Several types have been described (congenital, degenerative, pathologic, traumatic, and spondylolytic). However, most spondylolisthesis is secondary to spondylolysis, which represents a fibrous defect in the pars interarticularis or isthmus of the vertebra (Fig. 8-15). The disorder is therefore probably acquired and not congenital. The development of this defect has a hereditary predisposition and usually becomes manifested as the result of impact loading and extension stresses to the lower part of the back. These cause the development of an overuse fatigue fracture, usually bilateral, at the isthmus that fails to heal, resulting in a fibrous nonunion. It is most common at L5-S1. It develops in the teenage years, but may not become symptomatic until years later, if at all. It is often associated with lumbosacral anomalies such as transitional vertebrae and spina bifida occulta. There is an increased incidence in football players and gymnasts, possibly from hyperextension and chronic overload. If the defect is bilateral, forward displacement (spondylolisthesis) can occur. Spondylolisthesis is classified according to the amount of forward slippage of the affected vertebra (Fig. 8-16). An increase in slippage often occurs during the adolescent growth spurt but is rare after maturity.

CLINICAL FEATURES

Spondylolysis may be symptomatic even without spondylolisthesis, and both conditions may be associated with lumbar disc herniation. The disorder is often asymptomatic, however, and is frequently discovered incidentally in adults on roentgenograms taken for other purposes. When it is seen on roentgenograms taken as a part of a routine evaluation for back pain, it is often difficult to determine whether or not it is playing any role in the patient’s complaints.

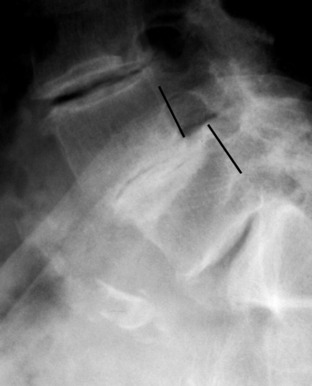

Roentgenograms reveal the typical findings of a defect in the pars interarticularis on both sides, which may be accompanied by forward slippage (Fig. 8-17). Unilateral defects are unusual. The classic findings of periosteal new bone present in stress fractures of long bones are rarely seen in the spine. A bone scan may be positive if the lesion is “acute” in the adolescent. MRI may be indicated in cases of negative bone scan to rule out other causes of pain. CT is also helpful to assess healing potential.

DEGENERATIVE SPONDYLOLISTHESIS

This type of spondylolisthesis results from disc degeneration and narrowing. When the process of disc “settling” is uneven, spondylolisthesis can develop (Fig. 8-18). The signs and symptoms are those of degenerative disc disease, sometimes accompanied by those of stenosis. Although many patients are pain-free, low back and occasionally radicular leg pain may develop. The treatment is the same as that for chronic degenerative disc disease and stenosis.

Back Pain in the Workplace

A variety of terms have been used to describe this condition, including “chronic benign industrial back pain” and “chronic pain syndrome.” This terminology partly reflects the difficulty in assigning a specific diagnosis and cause for the pain. A part of this difficulty, in turn, is a result of the fact that low back pain in general, and especially back pain in the workplace may be the result of a variety of biomechanical, biochemical, behavioral, socioeconomic, and psychophysiologic factors. In addition, trying to distinguish between a work injury and a normal disease of life can have profound implications for the patient.

EVALUATION

Physical findings are often nonspecific. There is usually generalized low back tenderness and diminished range of motion. Sometimes, the physical findings are “nonanatomic” in nature. Waddell signs are often cited when nonorganic physical findings are present (Table 8-3). There is usually no neurologic deficit, and sciatic tension tests are generally normal but may be difficult to assess.

| These findings should not be taken as a sign that no illness is present, but simply that this may be a way that patients can show how bad it is to them. |

SPECIAL STUDIES

All of the anatomic structures of the lower part of the back (discs, ligaments, facet joints, bone, and muscle) can be the source of pain. The intervertebral disc is thought by many to be the source of most low back pain. Unfortunately, as many as 35% of asymptomatic adults will have abnormal findings on myelography, CT, or MRI that are usually related to the disc. This makes evaluation of this problem difficult, and it is felt by many that in the majority of cases, the exact underlying pathology probably cannot be determined and the condition is simply called “idiopathic.” Initially, a routine roentgenographic examination should be performed in 2 to 4 weeks if the patient does not improve, mainly to rule out any serious disorder. Further studies (EMG, CT, MRI, bone scan, myelography) should be performed only as adjuncts to the physical examination and history. The yield of clinically useful information from these studies is often poor. Subjecting patients to further extensive testing in a search for the exact etiology of their pain is likely to be futile, sometimes painful, and always costly. Diagnosing a spinal disorder solely on the basis of any of these tests should be avoided. It is rare that these special tests clearly demonstrate a source for the pain when it is not suspected clinically. In addition, any treatment (e.g., surgery) based solely on a special study will often fail. In general, myelography and other special studies should be used only under the following circumstances: (1) if surgical disc removal is contemplated for intractable leg pain or a serious neurologic deficit, or (2) if other serious spinal abnormality is suspected.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

Thoracic Disc Disease

CLINICAL FEATURES

Only axial dorsal spine pain occurs in most cases. With central herniation and myelopathy, however, gradually increasing motor weakness in the lower extremities becomes apparent. Sphincter control may be lost, and diffuse numbness is common. Sensory testing may help determine the level of involvement. Examination usually reveals limited motion in the dorsal spine. Major neurologic deficits may be present in the lower extremities (spasticity, clonus). Roentgenographic examination often reveals calcification, narrowing, and spondylosis in the dorsal spine. Myelography may reveal a complete block in central lesions. MRI is often needed.

Scoliosis

CLINICAL FEATURES OF IDIOPATHIC SCOLIOSIS

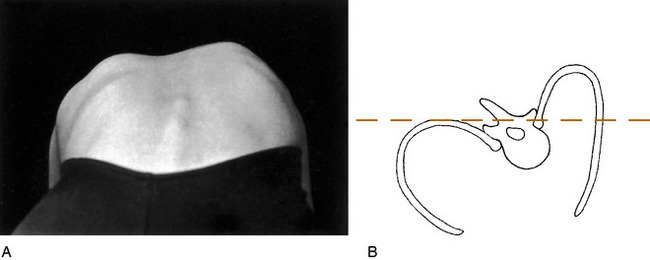

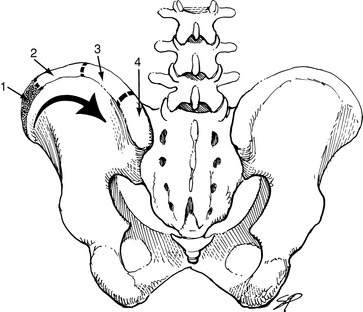

The diagnosis is usually made on routine physical examination. Attention should be focused on the problem in all children, but especially in those between the ages of 10 to 14 years, when spinal growth is most rapid. For the examination, the patient should be undressed to the waist or wear a bathing suit, and a routine should be followed. The shoulders and iliac crests are inspected to determine whether they are level. The scapulae, rib cage, and flanks are then observed for symmetry. The spinous processes are palpated to determine their alignment. The patient is then asked to bend symmetrically forward at the waist with the arms hanging free (Fig. 8-19). Observation from the back or front will detect the spinal rotation in the form of a rib hump or abnormal paraspinal muscular prominence. Height measurements are taken initially and at all follow-up visits to gauge the growth rate of the patient and assess the risk of rapid progression of the curve. Additional data should be obtained regarding skeletal and sexual maturity (onset of menses, etc.).

The diagnosis is confirmed, and the degree of curvature is measured by a standing roentgenogram of the spine (Fig. 8-20). There is no other method of determining the severity of the curve, and a patient should never leave the office without an accurate roentgenographic measurement of the curvature. The roentgenogram may have to be repeated at intervals to determine whether or not the curve is progressive. Breasts and gonads should be shielded when films are done. The degree of skeletal maturity can be determined by assessing the status of the iliac apophysis using the Risser sign (Fig. 8-21).