Fig. 10.1

Surface anatomy of the ankle – anterior view

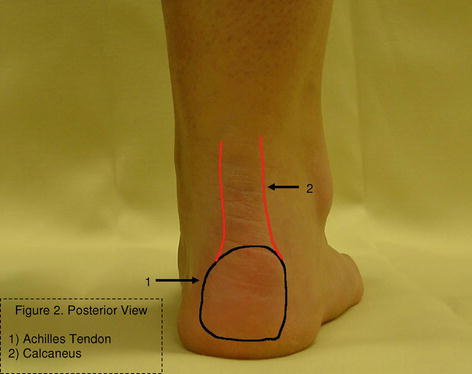

Fig. 10.2

Surface anatomy of the ankle – posterior view

Fig. 10.3

Surface anatomy of the ankle – medial view

Fig. 10.4

Surface anatomy of the ankle – lateral view

Red Flags

1.

Very young (prepubescent) or elderly patients. It is unusual for prepubescent children to have ankle sprains. One must consider a fracture that may involve the growth plate (physis) in these situations. This is because the physis is weaker than the ligaments about the ankle. These fractures, also called Salter-Harris fractures, can be quite serious, as poor healing can have implications for future bone growth. The Ottawa Ankle Rules (Table 10.1), a set of rules that help decide whether an ankle and/or foot x-ray is needed, have not been validated for children or the elderly. Therefore, all prepubescent and elderly patients with ankle injuries should have an x-ray.

Table 10.1

Ottawa Ankle Rules

For the patient presenting with malleolar zone pain: |

The patient should be able to take four steps (two loading and two unloading gait cycles) |

Palpate the posterior edge of the medial and lateral malleoli for tenderness |

Failure of either of these rules mandates a complete ankle series of radiographs |

For the patient presenting with midfoot zone pain: |

The patient should be able to take four steps as described above |

Palpate the base of the fifth metatarsal and navicular bone for tenderness |

Failure of either of these rules mandates a foot series of radiographs |

2.

A red or hot joint. In the presence of a red or hot joint, the clinician should consider the possibility of infection, neuroarthropathy (Charcot arthropathy), or inflammatory disease.

3.

Atypical pain. Pain that occurs at rest, pain that wakes the patient out of sleep at night, and bilateral ankle pain are atypical presentations of pain. These symptoms are concerning and may represent a more serious condition, such as a stress fracture, neuropathy, or radicular symptoms from an intervertebral disc herniation. Any patient with pain out of proportion to the clinical findings should be monitored closely or referred for further evaluation.

General Approach to Patient

History is the most important part of evaluating any musculoskeletal condition. The history portion of the exam should include the patient’s age, medical history, medication list, and mechanism of injury. It is also important to note location and intensity of pain and if the patient can bear weight.

Evaluation of the ankle begins with inspection. Take note of alignment with the patient in a weight-bearing position. Look for areas of swelling and/or ecchymosis after recent injury. A brief neurovascular examination must be performed on all patients, which includes sensation and palpation of the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibialis pulses. Assessment of the lumbosacral spine may need to be performed as well to rule out a secondary cause to the symptoms or a proximal nerve involvement (see Lumbar Spine chapter). Palpation of the major bony and soft tissue areas will assist the clinician in narrowing down the possible etiologies of pain (see anatomy pictures). Special tests can be performed to determine the status of the soft tissue. To evaluate the ligaments, the anterior drawer test and tibia/fibula squeeze test can be performed. To evaluate the status of the Achilles tendon, the Thompson squeeze test can be performed. Lack of foot plantar flexion with calf compression constitutes a positive Thompson test which is highly correlated with Achilles ruptures.

The Ottawa Ankle Rules are a guideline to determine whether or not a patient with an ankle injury needs further radiographic imaging. When used correctly, these rules have a sensitivity of 98 % for fracture (Bachman). It is important to note that these rules do not apply to the prepubescent and elderly patient (see “RED FLAGS”).

Lateral Ankle

The lateral ankle sprain is the most common cause of lateral ankle pain seen in the primary care setting. This injury typically occurs when the foot is plantar flexed and vulnerable to inversion. This will cause damage to the lateral ligament complex of the ankle. The anterior talofibular ligament is most commonly injured. In more severe injuries, the calcaneofibular ligament, which is the strongest of the lateral ligaments, may be injured. Patients with lateral ankle sprains may present to the office in an acute condition, or they may present one to two weeks after the injury if they continue to have problems. They will often have significant swelling and ecchymosis and tenderness to palpation over the involved ligaments and soft tissues.

The Ottawa Ankle Rules, as described above, should be applied to those patients with a lateral ankle sprain for the purposes of decision making regarding the need for an x-ray. However, if there is substantial concern, radiographs are appropriate. The individual ligaments can then be assessed by a few physical examination techniques, but this can be difficult in the acute setting because of patient guarding.

The ATF can be evaluated by using the anterior drawer sign with the knee at 90° of flexion and the foot in neutral position. The examiner will pull anteriorly on the heel to evaluate for a solid endpoint. Comparison with the non-injured ankle can be very helpful in determining the extent of injury. The CFL crosses both the ankle and subtalar joints. To test its integrity, the talar tilt test has been commonly recommended, but in the setting of an acutely injured ankle, this can be difficult to perform. Another method of assessing the CFL is to perform the anterior drawer sign with the foot in a slightly plantar-flexed position. The posterior talofibular ligament (PTF) is difficult to isolate on examination. Usually, when the PTF is injured, other injuries are present with the most common being fracture of the distal fibula.

A high ankle sprain involves the syndesmosis ligaments between the tibia and fibula and is important to distinguish from a lateral ankle sprain. Syndesmosis injuries are more likely to require surgical stabilization in the acute setting. This injury typically occurs with an external rotation mechanism. History of the injury is very important in determining mechanism and should raise suspicion of syndesmosis injury. The ligaments can be injured alone or in combination with a fracture of the ankle. Tenderness over the anterior ankle mortise and/or pain with tibia/fibula squeeze test can indicate an injury to this area. Pain can also be reproduced with passive dorsiflexion and eversion of the foot which stresses the mortise. Pain will usually be more severe than with a typical ankle sprain. Radiographs of the ankle and tibia should be obtained. A syndesmosis injury with a proximal fibula fracture is termed a Maisonneuve injury and is, by definition, unstable.

Most ankle sprains are self-limiting, but decreased morbidity can be obtained by using the PRICE protocol (protect, rest, ice compression, elevation of extremity). Weight bearing as tolerated, with the aid of crutches, may be recommended. A walking boot or cast will help with pain and ambulation in more severe injuries, but prolonged use should be avoided. Application of ice to the area for 20 min per session should be done four times daily during the acute phase. Compression can be obtained several ways such as ACE wrap or compression stocking. Functional bracing becomes important as the patient moves out of the acute phase and increases activity. This can be obtained with a lace up or hinged ankle brace.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree