Temporary Distraction Rods in the Correction of Severe Scoliosis

Lindsay M. Andras

David L. Skaggs

Temporary distraction rods allow significant corrective force to be applied directly to a deformed spine to aid in the correction of spinal deformity by working with the human body’s viscoelastic nature. In comparison to a vertebral column resection (VCR), it is our opinion that this technique may be safer in most spine surgeons’ hands as the steps are reversible. In comparison to halo gravity or femoral traction, we believe temporary rods allow more force to be applied to the localized area of the deformed spine, allowing for greater and/or more rapid correction. However, there is a bit more surgery with temporary rods than halo traction.

INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Temporary rods may be used in most cases of severe deformity of the thoracic and lumbar spine, including severe pelvic obliquity. The only requirement is that there is reasonable bone strength to anchor the rods near the top and bottom of the deformity. Anchor points may include the spine, pelvis, or ribs. In general, in most instances that halo traction is considered for a thoracic or lumbar spinal deformity, a temporary rod may also be considered.

This technique is contraindicated if continuous neuromonitoring of the spinal cord is not possible. We would be hesitant to use this technique in patients in whom the mean arterial pressure (MAP) cannot be raised to 80 mm Hg as this may affect cord perfusion. We are unaware of any cases of temporary distraction rods being utilized in the cervical spine. Temporary rods have been used in the treatment of kyphotic deformities, but this may represent a population at increased risk for neurologic injury from distraction. In cases of very rigid, short deformities such as congenital scoliosis or kyphosis, temporary rods are not likely to correct this part of the deformity, though they may help with significant correction above and below the apex of the deformity. VCRs may be considered for very short and rigid deformities, though in our institution neurologically intact children truly requiring a VCR are very uncommon. A relative contraindication is the inability of the patient to tolerate staged procedures due to significant medical comorbidities or poor nutritional status.

In our practice, we consider use of temporary rods with thoracic or lumbar scoliosis greater than 90 degrees, that does not correct to an easily fixable deformity with conventional techniques on traction or bending films, or pelvic obliquity not easily corrected on traction films, but this of course

varies greatly with the individual patient; a comparison of temporary internal distraction with halo-femoral and halogravity traction can be found in Box 43-1.

varies greatly with the individual patient; a comparison of temporary internal distraction with halo-femoral and halogravity traction can be found in Box 43-1.

BOX 43-1 COMPARISON OF DISTRACTION TECHNIQUES FOR CORRECTION OF SEVERE SCOLIOSIS

Temporary Rods

Offer ability to generate large, precise, and adjustable force directly at the spinal deformity, and avoid distraction outside of the deformity

A small amount of additional dissection required

Encourage patient ambulation between stages—preferred for idiopathic or neuromuscular patients who are independent ambulators

Allow seamless transition between a 1- and 2-stage procedure depending on findings at stage one. If signals are lost at stage one, or there is inadequate reduction at stage 1, adding a second stage may be beneficial and the improvement in deformity of stage 1 is preserved.

Authors’ preference for large stiff curves and curve types where one major curve is dominant

Have not been used in C-spine deformities

Intraoperative Halofemoral Traction

Ideal for flexible curves as it may make the exposure easier by the initial improvement

No additional dissection required

Theoretical downside is that the entire nerve tract (brain stem through nerve roots and major nerves in legs) is on stretch, which may increase chances of loss of neuromonitoring signals, when only distracting the area of spinal deformity is beneficial.

Useful in patients with exceptionally weak bone in which anchor plowing is a major concern

Addresses all components of the curve (particularly helpful in double major curves)

Useful in flexible cervical or cervicothoracic spine deformities

Can be used in conjunction with temporary rod (especially if transitioning to staged procedure)

Halogravity Traction

Allows awake monitoring of neurologic exam during distraction—ideal for highest-risk patients

Can be used prior to surgery for weeks to months or following anterior release and/or posterior osteotomies

Can allow for nutritional optimization (total parenteral nutrition [TPN] and supplementation can be utilized during this time) and in-hospital patient observation

Useful for rigid cervical or cervicothoracic deformities

Safe but slow option for deformity correction

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

Underlying medical conditions often accompany severe spinal deformities, necessitating attention to other organ systems (1). Cardiac or neurosurgical consultations are often indicated. Pulmonary consultation is frequently required. Children with severe pulmonary restriction are often nutritionally depleted, and this should be addressed before proceeding with staged spinal surgery, even considering placement of a gastrostomy tube.

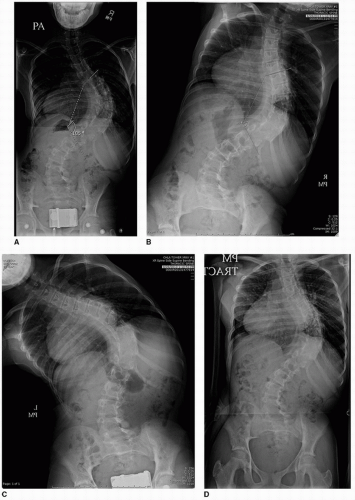

Standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs should be obtained. Traction films are more helpful than are bending films in most cases of severe spinal deformity. This is particularly true in predicting the usefulness of temporary distraction rods. In cases of pelvic obliquity, traction is applied only to the lower extremity on the side of the elevated hemipelvis in traction films. A general rule of thumb is that the first surgery with a temporary rod will be able to achieve better correction than the correction of a spinal deformity on a supine traction film in which the surgeon is pulling very hard (Fig. 43-1). As these patients have severe deformities and will be undergoing distraction of the spine, an MRI of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine is a standard preoperative study.

An advantage of the temporary rod technique is avoidance of an anterior spinal release, because correction through posterior surgery is generally sufficient. However, if a surgeon chooses to perform an anterior release, such as in the case of neurofibromatosis or spina bifida, this would be done before placement of the temporary rod.

Two operative procedures approximately 1 week apart should be discussed with the family, though in about 60% of cases, such as curves that correct to 70 degrees or better, the surgery is completed at 1 day. At the first surgical procedure, the temporary rod is placed in addition to any necessary posterior spinal releases and osteotomies. At the second surgical procedure, the temporary rod is removed, the final spinal implants are placed, and fusion is performed. When the tension on the temporary rod is released at the time of the second surgery, significant return of the spine to its previous deformity is not observed. Thus, having more than 7 days between these procedures would seem to add little additional correction. Additional procedures in which the temporary rods are lengthened over the course of weeks have been attempted, but have not been shown to significantly improve deformity correction. When the amount of correction obtained at the first surgery may be sufficient and neuromonitoring is stable, final fusion and instrumentation with removal of the temporary rods may be performed at the first surgery. (See Illustrative Cases 2 and 3.)

Preoperative planning should include evaluation of the bony anchor points for the temporary rod. An important principle in choosing anchor points for the temporary rod is to assume these anchors may plow through bone a bit, compromising the holding power of the final anchor. Thus, the temporary anchors should not be used as permanent anchors at either end vertebra of the final instrumentation. For example, because pedicle screws will plow upward in the upper thoracic spine during their use in securing a temporary rod, they should not be used as end vertebra anchor points in the final implant.

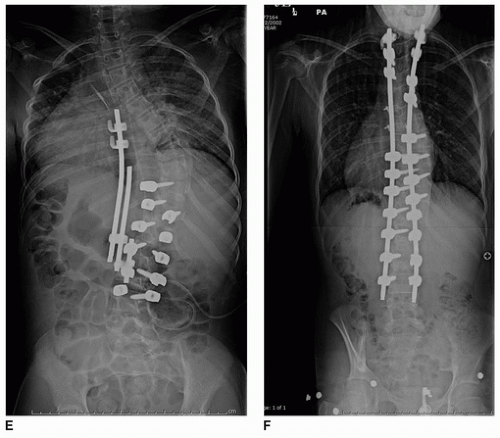

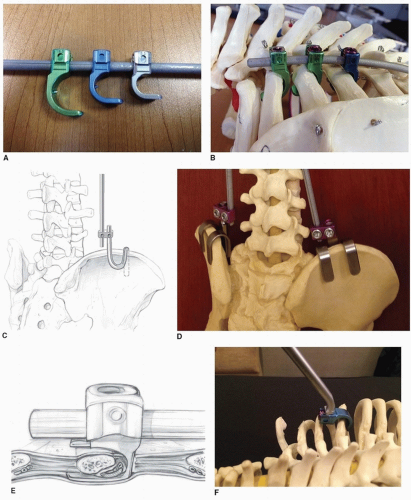

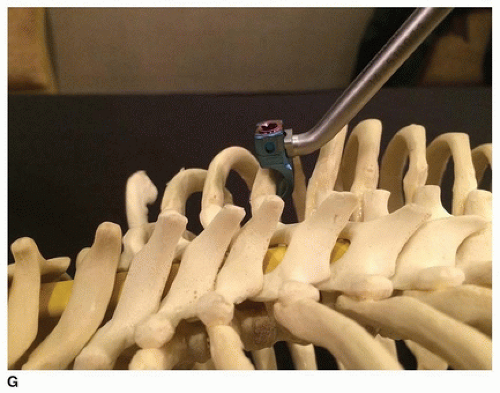

The upper portion of the rod is usually attached to the ribs. When attaching to ribs, standard spinal laminar hooks may be used, though newer instrumentation is designed to anchor to ribs, with a spike that helps prevent lateral slippage along the rib (Fig. 43-2A). Large sizes generally fit best. Anchoring to two or three ribs instead of one rib is recommended as this disperses the load (Fig. 43-2B). Significant forces are being applied, and temporary rods have been known to tear through a single rib. A major advantage of applying the temporary rod to the ribs rather than the spine is that it leaves the spine free; the permanent rod may then be placed on the spine, while the temporary rod is still actively applying distraction to the ribs.

We rarely use the spine for upper anchors; however, if one chooses to use the spine as an upper anchor point, hooks are generally preferable over pedicle screws. When pushing upward on thoracic pedicle screws, plowing through bone occurs more easily than when pushing downward. In addition, upgoing infralaminar or transverse process (TP) hooks have a little bit of “sloppiness” that allows for easier alignment. As the curves being treated with this technique are often greater than 100 degrees, one can imagine that two pedicle screws on adjacent tilted vertebrae are not going to point toward the bottom of the construct. When planning the placement of upper and lower anchor points, the ideal position is slightly above and below the most tilted vertebrae to allow these anchor points to line up with a straight distraction rod.

The bottom anchor points are usually in the lumbar spine or pelvis. Pedicles are generally stronger in the lumbar spine and the direction of force is downward, so the use of two pedicle screws as a distal anchor point works well.

In cases of pelvic obliquity or when the final fusion will be to the pelvis, the pelvis or iliac crest may be chosen as an anchor point for the temporary rod. This may be in the form of a pelvic saddle, S-hook (Fig. 43-2C

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree