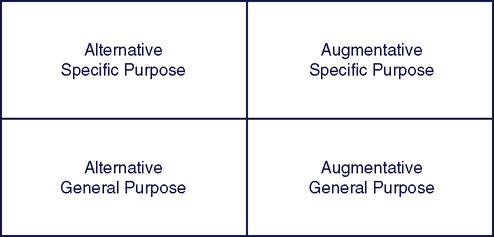

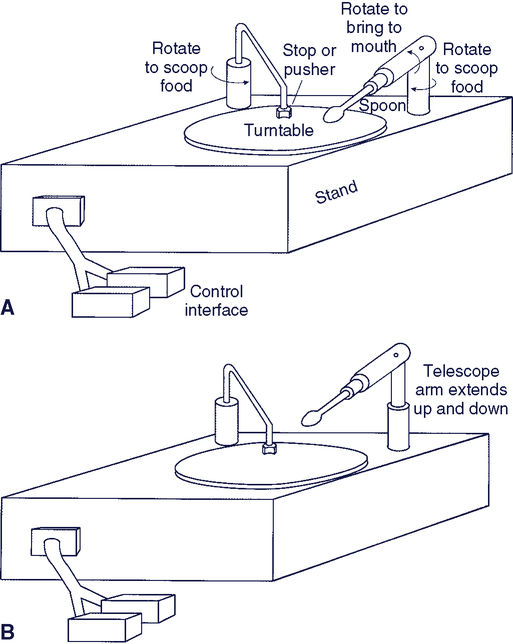

Upon completing this chapter, you will be able to do the following: 1. List functional manipulative tasks that can be aided by assistive technologies 2. Describe low-technology aids that are useful for self-care, school and work, and play and leisure activities 3. Describe the operation of electrically powered feeding aids 4. List the features and design properties of electronic page turners 5. List the functions carried out by electronic aids to daily living systems (EADL) 6. Describe an assessment process for determining the most appropriate EADL system 7. Describe the basic components of EADL systems and how they are implemented One of the activity outputs described in Chapter 2 (see Figure 2-7) is manipulation. At the most basic level, manipulation refers to those activities that we normally accomplish using the upper extremities, particularly the fingers and hand. Many types of “manipulation” are required to use assistive devices, especially those that are electronically controlled. For example, keys must be pressed for computer entry, joysticks controlled for powered mobility, and switches activated for communication devices. We have discussed this type of manipulation in previous chapters, and we exclude it from the general discussion of manipulation in this chapter. In this chapter, we describe gross motor manipulation as reaching, grasping/releasing, lifting, carrying, and coordination of movements such as pushing, pulling, and turning. Fine motor manipulation includes pinch, point, and dexterity of finger movements. The end goal of the integration of these manipulation components is a person’s actions in daily and life activities. For example, activities such as handwriting, food preparation, eating, reaching, using controls in the environment such as door handles and elevator buttons, and appliance control depend on manipulation of physical objects. These types of activities and the technology that supports them are our focus in this chapter. Figure 14-1 is a characterization of assistive technology devices used for manipulation. As in many other areas of assistive technology application, we can provide manipulative aids that are either alternative (a different method of doing the same task) or augmentative (assistance in doing the task in the same manner as it is normally done). For manipulation, we can also distinguish devices as being either specific purpose or general purpose. Specific-purpose manipulation devices are designed for only one task, whereas general-purpose manipulation devices serve two or more manipulative activities (see Chapter 1). For example, an augmentative, specific-purpose approach to eating may include a modified fork with an enlarged handle. An alternative, special-purpose apparatus for eating is an electromechanical device that lifts food off the plate and up to mouth level when a switch is pressed. A hand splint that allows gripping of any utensil serves as a general-purpose augmentative aid, since it can be used to hold a fork for eating or a pen for writing. In this chapter we discuss all four categories of assistive technologies for manipulation shown in Figure 14-1. The variety and choice of technology to assist with elements of manipulation have expanded greatly over the past several years. Often a commercially available tool or appliance will work very well for an individual with a disability to assist with manipulation. A commercially available gardening tool with an enlarged handle is an example of universal design, as described in Chapter 1, because it is useful by a wide range of individuals. Many implements for activities such as cooking and gardening are commercially available with enlarged or ergonomically designed handles. In a similar fashion, manufacturers are producing implements with telescoping or long handles. Follow the device selection guidelines described in Chapter 2 to identify devices that will assist a client with many manipulation tasks. Modification of implements they currently own or the purchase of commercially available implements is frequently a simple means to assist with manipulation. The definition of manipulation that was given at the beginning of this chapter suggested that it involves what we do with our upper extremities. Generally, it involves gross motor functions (larger and more forceful movement and function) and fine motor functions (smaller and more delicate movements). Fine motor coordination is considered to be “the smooth and harmonious action of groups of muscles working together to produce a desired motion.”6 Let’s look at the activity of dressing to illustrate gross and fine motor actions. Gross shoulder movements are needed to reach overhead, behind the back, across the midline of the body, and below the waist for lower extremity dressing. Elbow range of motion is needed to assist with reaching. Grasp and release are needed to grab and hold clothes while putting them on and taking them off. Strength is needed for grasp/release as well as to pull clothing up or down, on or off. Fine motor movements are necessary to use zippers, button and unbutton, tie shoelaces, and use fasteners behind the body (e.g., buttons or the hook and eye of a waistband). Gross motor functions important here include reaching; grasping/releasing an object; lifting and carrying an object; and actions such as pushing, pulling, and turning an object or control. In Chapter 1 we define low-technology aids as inexpensive, simple to make, and easy to obtain. Many manipulative aids fall into the low-technology category. We group these aids into general- and specific-purpose devices. Within specific-purpose devices, we categorize devices according to the major performance areas of the Human Activity Assistive Technology (HAAT) model: self-care, work or school, and play or leisure. The examples and other aids to daily living are available from many sources, including home health stores and online and mail-order catalogs.* To be classified as general purpose, a manipulation aid must serve more than one need. Three general purpose aids are described here because they are commonly found in most environments: mouthsticks, head pointers, and reachers. The first two of these are often used as control enhancers in conjunction with control interfaces. Head pointers and mouthsticks are discussed in Chapter 5, including their use as control enhancers for activating control interfaces. Both mouthsticks and head pointers are used for direct manipulation. Turning pages is often accomplished with a mouthstick or a head pointer used in conjunction with a book or magazine mounted on a simple stand. A ballpoint pen tip or a pencil can also be attached to a mouthstick for writing. Additional attachments include a pincher that is opened or closed by tongue action and a suction cup end that can be used to grip objects (e.g., a page) by sucking on the end of the mouthstick. Many tasks require sliding objects (e.g., paper, pens) around on a desk or table. Both mouthsticks and head pointers can be used for this task. Mouthsticks or head pointers can also be used for such functions as dialing a telephone, typing, and turning lights on and off. Self-care includes aids for assistance in several areas: food consumption, food preparation, dressing, and hygiene. Food consumption aids include a variety of modifications to utensils, such as enlargement and ergonomic shapes of handles, swivel handles so the bowl of the spoon retains a level orientation, lengthening of handles, and combinations of utensils called “sporks.” Modifications to plates include suction cups for stability, enlarged rims that make it easier to scoop food onto a utensil (scoop dish), and removable rims that attach to any plate (plate guard). Drinking aids include cups with caps and “sipper” lids through which fluid can be sucked, nose cutouts that allow drinking to occur without tipping the head back, and double-handled cups for two-handed use. Figure 14-2 shows a number of low technology devices to assist with food consumption. Dressing aids designed to compensate for poor fine motor control include adapted button hooks for single-handed buttoning and zipper pulls. These are available with enlarged, suction, and quad grip handles. For limited reach, there are aids for pulling on socks and pantyhose, long-handled shoe horns, and trouser pulls. A variety of dressing and hygiene aids are shown in Figure 14-3. A reacher is also shown in this figure. Examples of food preparation adaptations include one-handed holders for opening cans and jars, brushes with suction cups for one-handed scrubbing of vegetables, bowls with suction cup bottoms for stability while stirring with one hand, bowl and pan holders (some of which tilt for pouring), and cutting boards that stabilize food during cutting. Modified handles are available for knives and serving spoons, as well as for other utensils. Many of these devices are shown in Figure 14-4, which includes both commercially available and rehabilitation products. Other self-care items intended for use in the home include cuffs that are used to grip brooms and mops, extended handles on household items such as dustpans and dusters, and key holders. Many of these products are commercially available. Handwriting is a major need in work and school environments. Special-purpose manipulative aids that assist handwriting focus on one of two problems: holding the pen or pencil and holding the paper. Some consumers lack the ability to grip a standard pen or pencil. Low-tech approaches to this problem include modified grippers that attach to the hand and clamp to the pen or pencil; wire, wooden, or plastic holders that support the pen or pencil off the paper and allow it to slide across the paper; weighted pens (with variable amounts of weight) that help reduce problems associated with tremor; and pens with enlarged bodies to make them easier to grasp. There are several different designs for holding paper in place for one-handed writing. Generally the paper is attached to the support surface using either clips or a magnet (in this case the surface is steel). Desks with small tops can also be modified using a rotating “lazy Susan” device that rotates to bring items within reach. File folders are often modified for easier grasping by putting hooks or loops on them. The loop or hook protrudes above the folder so that it can be grasped more easily. High-tech aids for writing are discussed in Chapter 11. There are also low-tech reading aids. Book holders provide support for the reading material so the consumer does not have to hold it. Page turning is done either by hand or with a head pointer or mouthstick. In the next section we discuss electrically powered page turners and other electronic devices that aid reading. Figure 14-5 shows some low technology aids that can be used in work, school, or leisure settings. As with other types of manipulative aids, lack of grasping ability in recreational or leisure aids is generally accommodated for by altering the type of handle. Recreation and leisure examples include cameras with modified shutter releases, modified grip scissors, modified handles on garden tools, and modified grasping cuffs for pool cues, racquets, or paddles. A person with limited manipulation strength can fly a kite by adding special wrist or hand cuffs for holding the string. Similarly, someone with limited grasp can use a cuff to hold a hockey stick or golf club in order to participate in these leisure activities. Computer access methods that were described in Chapter 7 enable an individual to play computer games in the same way they provide access to educational materials. The most commonly available feeder is the Winsford Feeder®,* which is marketed by several mail order equipment companies. This feeder is illustrated in Figure 14-6. This feeder has rechargeable batteries that are used to power it at many different settings. It has an adjustable height base that can accommodate varying spoon height requirements. A chin-activated dual switch is mounted on a long, solid wire. When it is pushed in one direction, plate rotation occurs; and when it is pushed in the opposite direction, food is pushed onto the spoon and elevated to mouth level. The device can also be controlled by a hand or foot adaptation. Other dual switches or two single switches may be adapted to work with this feeder. Although the device is portable, it does take considerable space on a table so its use in community settings such as restaurants may be limited. These feeders require assistance from another person for setup of the device and preparation of the food. Food must be prepared so that it is either mashed or pureed or cut into bite-size pieces. Liquids such as soup are difficult to consume using these systems. In addition to the space they take on a table, the devices are not always reliable, causing unwanted attention to the user if food falls off the spoon onto their clothing or the table. In addition, because the device is unusual and large, the novelty of this method of eating might bring unwanted attention. So, while the device affords independent eating, once setup has taken place, its use might only be acceptable to the user in his own home. In the community or another social setting, the individual may choose to receive assistance from another person. This influence of location is an example of the social context from the HAAT model as well as resource allocation, both discussed in Chapter 2. Talking books, such as those made available for the blind, can also provide an alternative to physically manipulating pages. These are discussed in Chapter 8. Using a simple environmental control unit, a person with physical limitations can control the tape recorder and obtain access to the talking book at her own speed. Another approach is the use of books on computer disks. These can be loaded into a word processor, and the person needing access can use standard computer adaptations to turn the pages, scan through the material, find key words, and so on. This approach is also used by persons who have low vision or are blind, and we discuss it in Chapter 8. Both talking books and computer-based reading suffer from the limitation that not all reading material is available in these formats. The recent advent of e-readers and tablet computers has significantly enhanced access to books and other reading materials. The user can download reading material directly to the device or through a computer. They can be positioned on a stand to relieve the need to hold the device. Most include a touch screen as a method of turning the pages, which is completed in a very intuitive manner. Others have buttons to advance the pages. A mouthstick or head pointer can be used to turn the pages, providing the device is well stabilized. Many of these products have options to change font size. As these products become more available, add-ons are being developed that make them more accessible. For example Airturn (www.airturn.com) has a wireless hands-free device that allows the user to change pages through the use of a foot switch. Some of the devices have text-to-speech applications, although with varying reliability. Apple products can use the VoiceOver feature that is part of the Mac operating system. Others have proprietary software, which is inconsistently used by publishers of the material offered by the device manufacturer. A major limitation is that many of these devices do not have USB ports, which limits their modification through the connection to switches. However, third party applications are available that enable modifications to allow switch access. The Gewa page turner* (Figure 14-7) uses a rotating roller to separate pages from each other and then moves the entire roller from one side of the book or magazine to the other after the page has been separated. The standard control for the Gewa is a four-direction joystick. Two joystick directions cause roller rotation either clockwise or counterclockwise, and the other two cause the roller to move forward or backward. Any other four-switch control interface can also be used. An additional accessory for the Gewa is a scanning selection method in which a single switch is used to select one of the four control functions as they are presented in sequence. The display of functions consists of small LED indicators, with each labeled function corresponding to one joystick direction.

Technologies That Aid Manipulation and Control of the Environment

Manipulation

Low-technology aids for manipulation

General-Purpose Aids

Specific-Purpose Aids

Self-Care

Work and School

Play and Leisure

Specific-purpose electromechanical aids for manipulation

Electrically Powered Feeders

Electrically Powered Page Turners

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Technologies That Aid Manipulation and Control of the Environment