17 Systemic diseases

Cases relevant to this chapter

72, 84–85, 87–90, 93–94, 96, 99

Essential facts

1. The symptoms and signs of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) are diverse; non-specific constitutional upset characterized by malaise, low-grade fever, fatigue and unexplained weight loss is common.

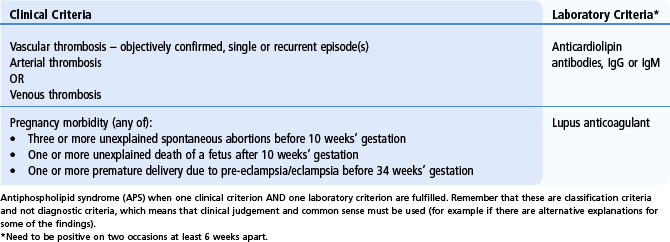

2. The antiphospholipid syndrome is characterized by recurrent thrombosis (arterial or venous) and/or pregnancy morbidity, and persistently raised levels of antibodies to phospholipid-related proteins.

3. There is a risk of malignancy in patients with dermatomyositis, particularly in the 2–3 years before and after the diagnosis of myositis is made.

4. Pulmonary hypertension is a complication of limited cutaneous scleroderma affecting 5–35% of patients.

5. Interstitial lung disease occurs in most patients with scleroderma, but progression to severe disease occurs in less than 20%.

6. Untreated multi-system vasculitis is fatal without potent cytotoxic or other immunosuppressive drugs and delay in diagnosis significantly affects morbidity and mortality.

7. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibody testing is helpful in supporting a diagnosis in patients who have suggestive clinical and/or pathological features of vasculitis.

Systemic lupus erythematosus

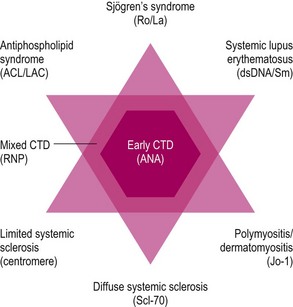

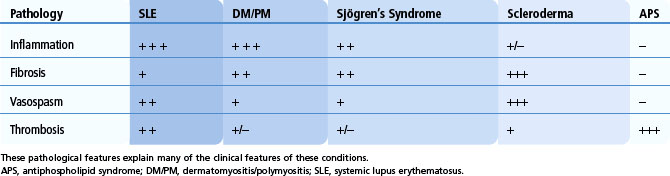

The autoimmune rheumatic diseases (formerly known as connective tissue diseases) represent a group of conditions that can be defined broadly as: multi-system inflammatory diseases of autoimmune origin associated with the anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) family of autoantibodies. A number of conditions fall within this family and autoimmune rheumatic diseases often show elements of overlap and similarity. These conditions have certain underlying pathological features that they share, but that occur relatively more frequently in some of the subgroups compared with others (Table 17.1). The four key pathological processes that underlie the autoimmune rheumatic diseases are inflammation, fibrosis or scarring, vasospasm and vascular thrombosis. The primary clinical features and many of the complications associated with these conditions can be deduced from these underlying pathological processes. Certain clinical/pathological features of these diseases are also more frequent with particular autoantibody subtypes. The presence of particular autoantibody subtypes may alert the clinician to investigate a particular organ or system for clinical features of relevance (Fig. 17.1).

Table 17.1 Relative occurrence of specific pathological features that underlie the autoimmune rheumatic diseases

Clinical features

The symptoms and signs of SLE are diverse, but, as indicated in Table 17.1, inflammation is the predominant pathology associated with many of the key clinical features. Non-specific constitutional upset characterized by malaise, low-grade fever, fatigue and unexplained weight loss are common in SLE. More specific inflammatory features include a malar or ‘butterfly’ rash, which is often light sensitive, and other cutaneous lesions including alopecia, mucosal ulceration and digital vascular changes such as nail-edge infarcts and splinter haemorrhages. Arthritis (small joint symmetrical polyarthritis) is also a common presenting feature. The arthritis is non-erosive, but in some cases ligamentous laxity can result in deformities similar to those seen in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (Jaccoud’s arthropathy; Fig. 17.2). In contrast to RA, however, these deformities are reducible. Importantly, SLE is also associated with inflammation in other organ systems, including serositis, nephritis and involvement of the central nervous system. Renal disease is often asymptomatic and can affect up to 25% of patients, although a higher occurrence is noted in African Caribbean, Chinese and Indo-Asian patients. Careful clinical assessment and regular urine examination is, therefore, necessary. A wide range of neuropsychiatric presentations have been described. Currently, the classification of SLE is based on a combination of clinical and laboratory investigations, and patients should have 4 of 11 criteria to confirm the classification of SLE (Box 17.1). However, it is important to remember that these criteria cannot be used as diagnostic criteria: they may assist in defining the spectrum of possible features but must be interpreted with common sense and clinical judgement and expertise.

Box 17.1

American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus (revised in 1997)

Thrombosis represents an important cause of clinical manifestations in lupus. The propensity to thrombosis is related to the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies, which reflect a pro-coagulant state. In addition, blood vessel inflammation can impair the normal anticoagulant properties of the endothelium. As a result, patients with SLE are at increased risk of venous thrombo-embolism, arterial thrombosis and adverse pregnancy outcomes (see antiphospholipid syndrome).

Up to 50% of patients with SLE also describe Raynaud’s phenomenon, although this is usually less severe and less likely to cause digital ulceration compared with that in patients with scleroderma. Typical skin changes include scarring or fibrosis, and a subgroup of patients with SLE present with discoid lupus lesions (Fig. 17.3), which are often discrete areas, associated with scaling, hypo- or hyper-pigmentation and loss of associated skin appendages. If discoid lesions occur on the scalp, this results in scarring alopecia.

Management of systemic lupus erythematosus

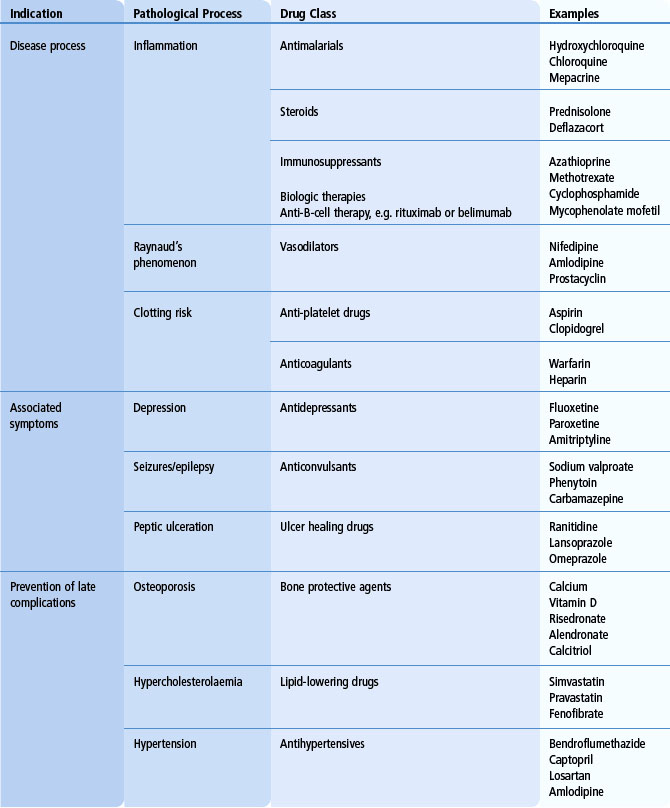

The aim is to make a clear diagnosis and to determine the extent of involvement. It is also important to determine whether specific clinical features can be attributed to inflammation, thrombosis or other disease mechanisms, as well as to exclude specific complications such as infection. For mild non-life-threatening disease, topical therapies, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and general lifestyle advice, such as avoidance of sun exposure, may be sufficient. For mild-to-moderate disease, anti-malarial drugs (hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine phosphate), methotrexate, leflunomide, azathioprine and/or low-dose corticosteroids are frequently used. In patients with significant organ involvement, e.g. proliferative glomerulonephritis, severe neuropsychiatric involvement or uncontrolled generalized disease, immunosuppressive drugs, such as cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate mofetil, are indicated. Because of the risks of long-term toxicity from cyclophosphamide, most patients are switched to maintenance azathioprine or mycophenolate following successful initial disease control. More recently, novel therapies, such as anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, have shown limited efficacy in refractory disease. In addition to these therapies, other specific agents to control symptoms and/or to prevent complications are commonly required (Table 17.2). These therapies include anticonvulsants, anticoagulants, antihypertensives, lipid-lowering drugs and bone protective agents.

Antiphospholipid syndrome

Clinical features (Table 17.3)

Vascular thrombosis

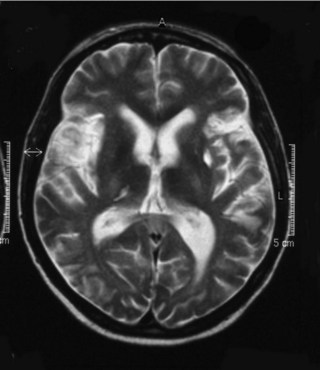

Thrombosis associated with APS can occur in any part of the circulation. The most important thrombotic complications include deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism as well as stroke (Fig. 17.4), myocardial infarction and retinal artery occlusion. Untreated, there is a high risk of recurrent thrombotic events and, indeed, a careful clinical history may reveal previous unexplained thrombotic episodes in the distant past. Patients with APS can experience thrombosis on the venous and arterial side of the circulation, although it is more common for recurrent thrombosis to occur on the same side of the circulation as the previous thrombosis.

Other clinical features

Approximately one-third of patients with APS have thrombocytopenia, which is usually a chronic stable thrombocytopenia (50–150 × 109/l). In addition, about 15% also have a Coombs-positive haemolytic anaemia. Cutaneous features associated with APS include livedo reticularis (Fig. 17.5), superficial thrombophlebitis and chronic leg ulcers. On careful screening, patients with APS frequently have thickening of cardiac valves, and 20–30% may have clinical evidence of mitral valve prolapse. In the central nervous system, clinical syndromes such as transverse myelitis, chorea and migraine may occur. It is, however, unclear whether these are primarily thrombotic in nature or whether they represent a separate pathogenic mechanism. Occasionally patients can present with thrombosis in multiple vascular beds. This ‘catastrophic’ antiphospholipid syndrome is difficult to recognize clinically and is associated with a high mortality rate.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree