Synovial-Based Disorders

Jared Thomas

James R. Ross

Michael J. Salata

Rick Bancroft

Asheesh Bedi

DEFINITION

Synovial-based disorders about the hip are relatively rare entities. Synovial chondromatosis and pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) have been increasingly of interest to hip arthroscopists and will be the primary focus of this chapter. Inflammatory arthropathies and septic arthritis will also be discussed, as they are often grouped with the cited conditions and are amenable to similar surgical interventions.

Synovial chondromatosis is a benign, typically monoarticular neoplastic process characterized by nodular cartilaginous proliferation arising from the synovial tissue of joints. Hyaline cartilage nodules initially form within synovial tissue, progressively enlarge, and eventually detach from the synovium. This repetitive process may result in numerous intra-articular loose bodies and is known as primary disease. Secondary synovial chondromatosis differs in that a preexisting joint pathology causes similar intra-articular loose bodies.

PVNS is a proliferative process of unclear etiology that results in chronic inflammation and characteristic hemosiderin deposition within the synovium. PVNS can be either focal, involving only a portion of a given joint’s synovium, or diffuse, involving the entirety of a joint’s synovial tissue.

ANATOMY

Synovium is a highly specialized tissue that lines the intraarticular structures of a joint. It is composed of two to three layers of synoviocytes covered by a loose connective tissue composed of collagen, fat, and blood vessels.

In addition to acting as a mechanical shock absorber, the synovium also produces synovial fluid and hyaluronic acid, which together provide nourishment and lubrication to the articular surface.

The hip joint is represented by the articulation between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the pelvis. The femoral head is deeply recessed within the acetabulum, creating an inherently stable joint.

In addition to the relatively constrained bony anatomy, a thick fibrous capsule with ligamentous condensations (pubofemoral, iliofemoral, and ischiofemoral ligaments) provides further stability to the hip joint, particularly in terminal range of motion.

The hip joint is further covered by a large soft tissue envelope consisting of muscular, tendinous, and neurovascular structures.

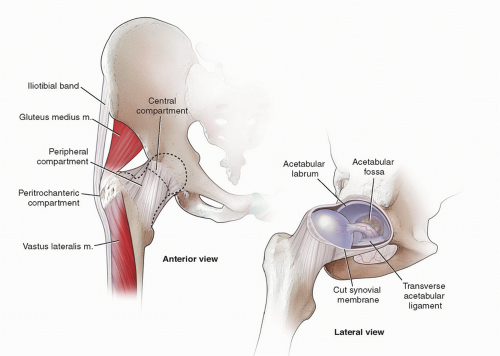

The complex anatomy of the hip can be divided into three compartments, which are relevant when discussing arthroscopic treatment of various hip pathologies (FIG 1):

Central compartment, which consists of the capsule, acetabular labrum, acetabulum, femoral head, and ligamentum teres. Together, these structures are often referred to as the hip joint proper.

Peripheral compartment, the structures of which are described as extra-articular, however, remain intracapsular. The zona orbicularis is considered the quintessential landmark of the peripheral compartment and is a thickening in the hip capsule, which wraps circumferentially around the femoral neck. Other landmarks in the peripheral compartment include the medial and lateral synovial folds, the psoas tendon, and the femoral head-neck junction.

The lateral synovial fold contains the intracapsular penetrating arteries, which provide the major blood supply to the femoral head.

Lateral/peritrochanteric compartment, which is the space between the proximal femur and the iliotibial band. Structures that can be visualized within this compartment include the insertion of the gluteus maximus, medius, and minimus tendons and the proximal vastus lateralis.

Synovial disorders can arise and/or extend into any of the mentioned compartments and complete, systematic evaluation of all three compartments is indicated when performing hip arthroscopy for synovial pathologies.

PATHOGENESIS

Synovial chondromatosis may exist in three temporal phases as described by Milgram.6 During phase I, the synovial disease is active in the production of nodular cartilaginous proliferations; however, no intra-articular loose bodies are present. Phase II involves continued synovial proliferation with the presence of loose bodies within the joint. The synovium becomes quiescent in phase III; however, the loose bodies remain.

The intra-articular loose bodies may result in mechanical injury to the chondral surfaces of the femoral head and/or the acetabulum via third-body wear.

Synovial chondromatosis may also affect the bursae and tendon sheath of large joints, which around the hip include the psoas tendon and bursa.

PVNS is an idiopathic, monoarticular reactive synovial disease that has been described as either a nodular or diffuse pattern. It is characterized by proliferation of synovial villi and nodules. This process leads to joint destruction via several mechanisms, including recurrent hemarthroses and chronic inflammation leading to caustic damage to the articular surface as well as loose body formation, which may lead to mechanical damage similar to synovial chondromatosis.

The constrained nature of the hip makes it more susceptible than other joints to bony erosion and destructive changes in the course of synovial disorders.

Chondrocalcinosis can be encountered and is important to recognize. It is most frequently caused by calcium pyrophosphate dihydrate (CPPD) crystal deposition within a particular joint. This is often characterized by crystalline deposition within the acetabular labrum and/or the articular cartilage.

NATURAL HISTORY

Three distinct phases of synovial chondromatosis have been described:

Early: active synovial disease and the absence of loose bodies

Transitional: active synovial disease with loose bodies

Late: cessation of active synovial disease with loose bodies

Although synovial chondromatosis is self-limited in some cases, progressive disease leading to osteoarthritis is of primary concern when developing a management strategy. Prompt removal of loose bodies and inflamed synovium is important for both symptomatic relief and prevention of long-term complications.

There is a 5% reported incidence of conversion to synovial chondrosarcoma, which should be suspected with atypical presentation such as rapid onset, extra-articular involvement, and multiple recurrences.

Patients with PVNS often present in a delayed manner, after joint degenerative changes have already begun. Due to the higher likelihood of articular destruction at presentation, synovectomy alone is less likely to result in substantial clinical improvement.

Chondrocalcinosis results in crystalline deposition into the acetabular labrum and the articular cartilage, thus altering the mechanical properties making them more susceptible to breakdown.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients who present with synovial disorders often have vague complaints that are insidious in onset. These complaints include pain that is typically worse with activity, stiffness, swelling, joint instability and mechanical symptoms, such as locking and catching. Deep groin and deep lateral hip pain are also common presenting complaints associated with synovial disease involving the hip joint.

The spectrum of synovitis can be distinguished from septic arthritis by the absence of rapidly progressing pain, extreme irritability with movement, and constitutional symptoms. The distinction is of the utmost importance as joint sepsis necessitates emergent intervention.

FIG 2 • Numerous loose bodies arthroscopically recovered from a single hip joint of a patient with synovial chondromatosis.

A reported history of trauma to the joint is sometimes present in patients with PVNS; however, a direct correlation has not been convincingly established.

Physical examination findings are similar for all benign synovial disorders and can be the result of synovial inflammation, loose body impingement, or the degenerative joint changes evident in later stage disease. Most common general findings include decreased range of motion, erythema, warmth, and tenderness to palpation about the affected joint. It should be noted that swelling and other superficial physical examination findings are often absent in hip synovitis due to the large soft tissue envelope around the joint.

Hip examination often reveals pain with range of motion that is most pronounced at the terminal ranges of motion. Decreased range of motion is also common secondary to inflammation and/or capsular distension from the loose bodies.

Examination maneuvers that may be positive include Patrick (FABER) test, anterior impingement test, and abduction internal rotation test (see Exam Table).

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Imaging studies are the most reliable way to distinguish among the various benign synovial disorders as well as identify other possible causes of hip symptomatology with several characteristic findings described.

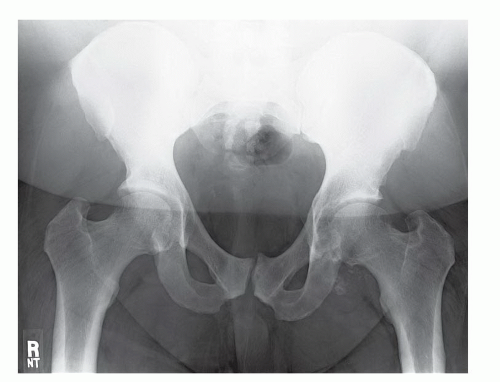

Anteroposterior and lateral (cross-table, frog-leg, and Dunn view) radiographs of both hips are the preferred initial series, especially for the evaluation of associated femoroacetabular impingement morphology.

Plain film radiographic results can range from a normal x-ray to one showing either multiple loose bodies (FIG 3)

or degenerative changes depending on the disease process and/or stage.

FIG 3 • Anteroposterior x-ray of the pelvis from a patient with synovial chondromatosis. Note the loose bodies about the left hip.

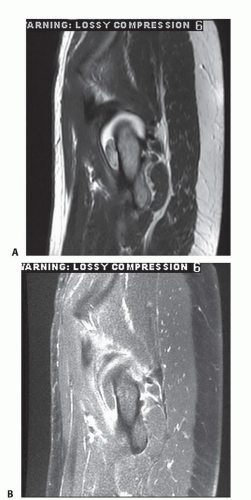

FIG 4 • A T2-weighted magnetic resonance image of the pelvis showing multiple loose bodies in the left hip of a patient with synovial chondromatosis.

When present, periarticular erosions and reciprocal bony lesions often without evidence of articular involvement are x-ray findings suggestive of PVNS.

The majority of patients with PVNS, however, have no findings on initial plain x-ray.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (FIG 4), computed tomography (CT), and/or arthrography may be helpful if loose bodies are suspected and not seen on plain films, as is often the case early in the disease process prior to the calcification of nodules and/or loose bodies.

In general, magnetic resonance arthrography is considered the gold standard for assessing hip soft tissue pathology as well as intra-articular, nonossified loose bodies.

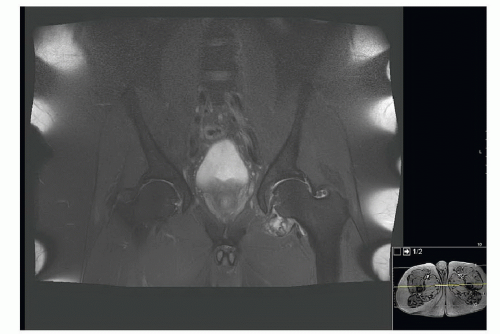

MRI findings consistent with PVNS include similarity of lesion appearance on both T1- and T2-weighted images. This is classically referred to as a dark-on-dark appearance and is due to the high hemosiderin content (FIG 5).

Despite the crucial role of imaging in the diagnosis of synovial disorders, many cases of PVNS, synovial chondromatosis, and their associated loose bodies are first appreciated during arthroscopy. Nearly 50% of patients who underwent hip arthroscopy for synovial chondromatosis in a 2011 study by Marchi et al5 were not diagnosed with preoperative imaging, which included gadolinium-enhanced MRI.

Arthrocentesis is generally not recommended in patients with suspected synovial disorders unless one is concerned for infection or crystalline arthropathy. When performed, synovial fluid most often appears brown stained in patients with PVNS and a normal clear or straw color in most cases of synovial chondromatosis.

Laboratory values such as complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein are often normal in most cases of synovitis and should be analyzed when one is concerned for an infectious process.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Primary villonodular synovitis

Synovial chondromatosis

Septic arthritis

Hemarthrosis

Lipoma arborescens

Synovial hemangioma

Tumoral calcinosis

Crystalline arthropathy (gout/pseudogout/chondrocalcinosis)

Inflammatory arthropathy (rheumatoid arthritis)

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

In patients who have mild symptoms and retained range of motion, observation with careful monitoring can be considered. However, most patients with benign synovial disorders have endured a significant delay in diagnosis and as a result have failed conservative management at the time of presentation to the orthopaedic surgeon.

Although studies involving the hip joint are lacking, PVNS has been shown to be responsive to radiation therapy in the form of both external beam and intra-articular injection of radioactive isotopes, which can be used to achieve a result similar to surgical synovectomy in the knee.7 More recently, this modality has been advocated as an adjunct to surgical management to reduce the incidence of recurrence.9

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

The goal of surgical management is to remove all abnormal synovium to improve symptoms as well as eliminate or lower the possibility of recurrence while reducing pain and minimizing the risk of joint destruction.

Although open approaches have been traditionally used for surgical management, arthroscopy has been recently employed to accomplish the mentioned goals while at the same time avoiding the potential complications and prolonged recovery of an open procedure, surgical dislocation, and/or radiation. Arthroscopic procedures may also allow for a potentially faster recovery given the less invasive nature of the approach. However, open surgery may be indicated and favorable in cases of nonfocal, diffuse PVNS with extension in both intra- and extra-articular compartments to avoid the risk of recurrence secondary to an incomplete synovectomy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree