Syndrome of Inappropriate Secretion of Antidiuretic Hormone

Arundhati S. Kale

Hyponatremia occurring as a result of the release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) that is not attributable to osmolar- or baroreceptor-mediated stimuli is called the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of ADH (SIADH).

NORMAL PHYSIOLOGY

Normally, ADH is released from the posterior pituitary in response to changes in plasma osmolality and effective circulating blood volume. Serum osmolality is maintained in a very narrow range, with only a 1% to 2% change altering the secretion of ADH via the osmoreceptors, whereas a larger change in volume (approximately 10%) is needed to affect the carotid and left atrial stretch receptors to stimulate or inhibit ADH release.

PATHOGENESIS

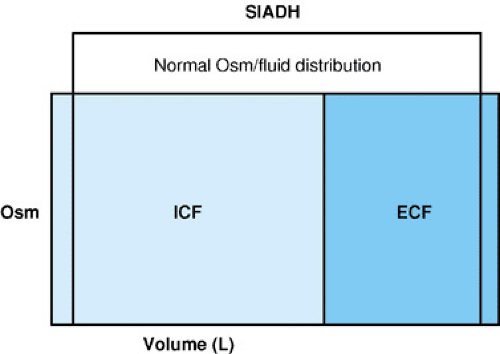

The initial event leading to SIADH is ADH-induced water retention, leading to volume expansion and natriuresis. The mediator of natriuresis may be atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), together with suppression of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. The continued ingestion or infusion of fluids in the presence of persistent antidiuretic activity leads to dilutional hyponatremia. Excess water reabsorption decreases serum osmolality, causing water shifts into the intracellular fluid (ICF) and cell swelling (Fig. 458.1). No visible edema is apparent because of the expansion of both the intracellular and extracellular spaces. Patients with SIADH continue to drink fluids despite the presence of hypotonic hyponatremia because the inhibitory effect of osmoregulated thirst is not sufficiently strong to halt drinking.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND COMPLICATIONS

The physical findings in SIADH are related to the associated disease process. Despite mildly increased total body water, the formation of edema typically is not seen. Symptoms are related to the presence and duration of hyponatremia. Anorexia, nausea, changes in mental status, and convulsions are more likely to occur with the acute onset of a serum osmolality of less than 240 mOsm/kg H2O and a serum sodium concentration of less than 120 mEq/L; the faster the rate of fall, and the lower the serum sodium concentration, the more severe the symptoms. Most patients will remain asymptomatic if serum sodium concentration is greater than 120 to 125 mEq/L over a long period of time (greater than 3 days).

Associated Disorders

In children, SIADH occurs most often in association with central nervous system (CNS) disorders. Laboratory evidence of SIADH was noted in almost 60% of children presenting with bacterial meningitis. ADH levels in patients with meningitis also were elevated significantly in comparison with normal and febrile controls. The duration and degree of hyponatremia was shown to correlate significantly with the subsequent development of seizures and subdural effusions. A leak of endogenous ADH across inflamed meninges has been suggested to explain these findings, but laboratory markers of inflammation did not show a correlation with arginine vasopressin (AVP) levels. SIADH occurs with other CNS infections, including brain abscesses and encephalitis, and with Rocky Mountain spotted fever, most likely secondary to the hypothalamic involvement from rickettsial vasculitis. Such CNS disturbances as head trauma, perinatal hypoxia, brain tumors, subarachnoid hemorrhage, anatomic defects, and Guillain-Barré syndrome may produce SIADH.

Intrathoracic disturbances are less common causes of SIADH in children. Pulmonary tuberculosis is well recognized, but viral, fungal, bacterial, and mycoplasma pneumonias also have been cited. Disorders that lead to decreased left atrial pressure, such as positive-pressure ventilation or pneumothoraces, can induce an excessive release of ADH by diminishing venous return. This condition is perceived inappropriately by stretch receptors as evidence of decreased circulating blood volume. Levels of ADH probably are elevated by a similar mechanism in status asthmaticus, leading one to reconsider the vigorous use of intravenous fluids often recommended in initial management.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree