, James B. Galloway2 and David L. Scott2

(1)

Molecular and Cellular Biology of Inflammation, King’s College London, London, UK

(2)

Rheumatology, King’s College Hospital, London, UK

Abstract

As pain is the main symptom that inflammatory arthritis patients report, analgesics are a major focus of their management. Simple analgesics such as paracetamol and Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) are commonly used. Both have risks when used long-term. A particular concern with long-term NSAID use is an increased risk of cardiovascular and gastrointestinal events such as myocardial infarction and gastro-oesophageal bleeding. This chapter will provide a broad overview of symptomatic drug treatments in inflammatory arthritis patients. It will focus on the different classes of available treatments, their relative merits and disadvantages, alongside their use in the different forms of inflammatory arthritis.

Keywords

AnalgesicsParacetamolNSAIDsSide-effectsIntroduction

Pain is the dominant symptom in arthritis. It is present from the earliest stages of synovitis and persists throughout the course of the disease. In early inflammatory arthritis pain is predominantly related to the activity of the synovitis. In late disease it is influenced by the development of joint damage and failure.

Pain in arthritis overlaps with chronic pain generally, which is a major medical problem. Nearly half the adult population report chronic pain. It is particularly prevalent in the elderly and is also associated with poverty, being retired and being unable to work. Arthritis is the commonest cause of pain in the community.

The impact of poorly controlled pain cannot be overestimated in inflammatory arthritis. Almost all patients with inflammatory arthritis report pain is a major health problem. Pain has close links with psychological symptoms including depression and anxiety. It is also closely related to disability and impaired health status.

There are several ways to control pain. The first and most important is to give symptomatic drug treatment with analgesics or anti-inflammatory drugs. The second is to control the underlying inflammatory disease process. The third is to replace damaged joints, which is only relevant in late disease. Finally non-specific measures such as exercise therapy or treating co-existent depression also reduce pain, and the benefits of anti-depressants may extend beyond merely treating depression into a direct effect on pain itself.

Other important symptoms in arthritis stem from joint inflammation. Pain is accompanied by joint tenderness, swelling and stiffness, together with morning stiffness. Symptomatic treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs improves stiffness and tenderness and to some extent will reduce joint swelling. The effect of symptomatic treatment on joint tenderness and swelling is less than that of disease modifying treatments.

Simple Analgesics

Simple analgesics should be used in all patients with inflammatory arthritis as an adjunct to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and DMARD therapy. The available drugs include paracetamol, co-proxamol and tramadol (Table 5.1). Although there is some evidence from clinical trials that analgesics reduce pain in RA, the amount of data is very limited. Most trials of these drugs were carried out more than 20 years ago and by current standards did not study enough patients and did not last long enough. However, almost all rheumatologists recommend using them. At the same time, only a very small proportion of patients with RA and other inflammatory arthropathies will have their disease controlled by analgesics alone.

Table 5.1

Commonly used analgesics

Simple | Compound |

|---|---|

Paracetamol | Co-codamol (paracetamol/codeine) |

Codeine | Co-dydramol (paracetamol/dihydrocodeine) |

Dihydrocodeine | |

Tramadol | |

Buprenorphine |

Paracetamol

Paracetamol is the dominant analgesic. It is effective with a single dose of 1,000 mg paracetamol providing more than 50 % pain relief over 4–6 h in moderate or severe pain compared with placebo. Its analgesic effects are comparable to those of conventional NSAIDS, there are virtually no groups of people who should not take it, interactions with other treatments are not a problem, at the recommended dosage there are virtually no side-effects, it is well tolerated by patients with peptic ulcers.

Interestingly despite being used for many years the mechanism of action of paracetamol is not well understood. It may be centrally active, producing analgesia by elevation of the pain threshold by inhibiting prostaglandin synthetase in the hypothalamus. At therapeutic dosages it does not inhibit prostaglandin synthetase in peripheral tissues, and consequently has no anti-inflammatory activity.

Although paracetamol has been used to control symptoms in inflammatory arthritis for many years, the evidence supporting its efficacy remains weak [1]. The weakness of this evidence is, however, partly related to the historic nature of the drug. The evidence base for many long-standing drugs is weak because the need for strong evidence when they were introduced was minimal.

One limitation with paracetamol is that it is relatively ineffective, patients need to take 6–8 tablets daily to achieve any analgesic benefit, and most patients prefer to take NSAIDs. Patients’ perspectives highlight the limitations of paracetamol. Only a minority of patients find it is effective and the majority prefer NSAIDs for symptom control.

Historically the safety of paracetamol has been emphasised. However, there are concerns about its potential toxicity with therapeutic doses. These include:

liver injury, especially in patients with underlying liver disease, malnutrition and chronic alcohol use

renal disease, with evidence of reduced renal function in patients who have taken paracetamol

hypertension, which has been identified as a possible risk in large observational studies.

Opioids

These are widely used to control pain. In arthritis weak opioids (codeine, dextropropoxyphene and tramadol) are often used, whist strong ones (morphine and its derivates) are avoided. Although these drugs are effective in chronic non-cancer pain, many patients stop taking them due to side effects. These reactions include nausea, constipation and drowsiness.

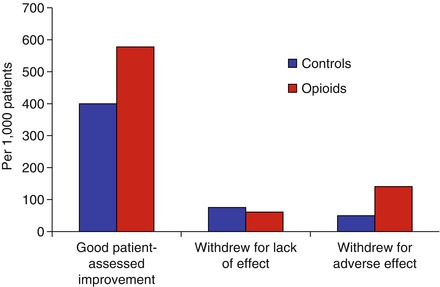

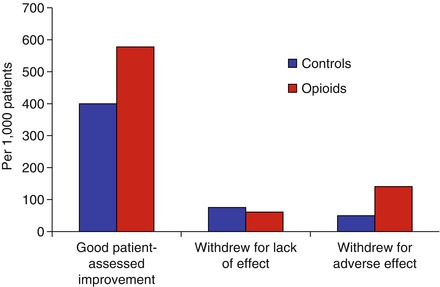

The reasons that strong opiates like as morphine are virtually never used in treating inflammatory arthritis are complex. It is usually thought that their addictive nature makes their over value more disadvantageous than beneficial. However, this view is based on custom and practice rather than any rigorous scientific testing. A small minority of patients do benefit from them. There is reasonable evidence opioids are effective in improving symptoms in inflammatory arthritis, particularly patient-reported pain levels, although adverse events such as nausea are not uncommon (Fig. 5.1) [2].

Figure 5.1

Efficacy and toxicity of opioids in rheumatoid arthritis (From systematic review by Whittle et al., figure adapted using data reported by Whittle et al. [2])

Tramadol

Tramadol is effective in relieving moderate to moderately severe pain. It is a weak synthetic opioid that also has serotonin-releasing and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitory properties. It is used to treat moderate to severe pain in arthritis. Tramadol causes less constipation than conventional opiates. Dependence is not a clinically relevant problem. To be fully effective tramadol needs to be given at a dose of 50–100 mg every 4–6 h. A slow release formulation can be useful if night pain is a particular problem. Its most frequent adverse effects include headache, dizziness and somnolence. The sleepiness caused by tramadol often precludes its use in patients who need to be mentally alert in the day. Tramadol is closely regulated and in the United Kingdom it is now classified as a schedule three controlled drug.

Buprenorphine

Buprenorphine is now available as a transdermal preparation for treating the pain of arthritis. It is an opioid analgesic. The patches have reservoirs of buprenorphine which is slowly absorbed into the blood. Patches need to be changed weekly to deliver continuous pain relief. The use of transdermal treatment reduces some of the adverse effects of opiates such as constipation and nausea. It also provides more continuous efficacy.

Codeine and Dihydrocodeine

These weak opioids have centrally mediated effects. They are effective after 20–30 min and last for about 4 h. Dihydrocodeine has about twice the potency of codeine. They show a ceiling effect for analgesia and higher doses give progressively more adverse effects, particularly nausea and vomiting. These adverse effects outweigh any additional analgesic effect.

Compound Analgesics

Patients can combine paracetamol with a weak opiate as single agents or in combination tablets. Co-proxamol, which is the combination of paracetamol with dextropropoxyphene (an agent that is rarely used alone), was historically popular with clinicians. There was no obvious reason for this and the drug has been withdrawn from general use. Currently available combinations comprise paracetamol with codeine (co-codamol) or dihydrocodeine (co-dydramol). These compound drugs have the same effects and adverse reactions as individual drugs.

Non-steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs are a diverse group of drugs with a name that was introduced to distinguish them from glucocorticoids and the non-narcotic analgesics. Overall NSAIDs are one of the most frequently used group of drugs. Their benefits must be set against significant risks from gastrointestinal and renal toxicity, which cause a substantial number of deaths each year.

Mechanism of Action and Cox I/Cox II Effects

Inflammation involves many locally produced chemical mediators. These include prostaglandins, leukotrienes, complement-derived products, and products of activated leukocytes, platelets and mast cells.

The central and most important effect of NSAIDs is inhibiting cyclo-oxygenase (COX). COX has been presumed to be the major target of NSAIDs for many years influencing their analgesic and anti-inflammatory capacities. It was originally purified in the 1970s. By 1990 it was realised the enzyme had two isoforms, termed Cox I and Cox II [3]. The first isoform – COX- 1 – is responsible for the production of “housekeeping” prostaglandins critical for normal renal function, gastric mucosal integrity and vascular haemostasis. By contrast COX-2 is an inducible enzyme. It is upregulated in macrophages, monocytes and other inflammatory cells by various stimuli including interleukin-1 and other cytokines. NSAIDs can be classified according to their relative effects on Cox I and Cox II. The risk of GI adverse effects seems to be reduced with increasing Cox II selectivity. However, other factors are involved, as some NSAIDs that are relatively Cox II selective are known to be associated with a higher incidence of GI adverse events.

Several types of assays assess the Cox-II selectivity. In vitro human whole blood assay is an accepted and reproducible standard. However it may not truly reflect the Cox inhibition in target tissues like the gastric mucosa. Recent assays use human target cells such as gastric mucosal cells and synoviocytes. There are wide variations in ratios reported by using different assay techniques. Results from in vitro testing are no more than a general guide to the relative in vivo selectivity of different drugs.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree