Syme and Boyd Amputations for Fibular Deficiency

Anthony Scaduto

Robert M. Bernstein

DEFINITION

Fibular deficiency, previously known as fibular hemimelia, is a longitudinal deficiency of the fibula. It is the most common long bone deficiency and may be either partial or complete.1

A wide spectrum of associated anomalies also may be seen on the affected limb. The extent of limb shortening and the degree of foot deformity are the most important components that determine treatment. Treatment options include use of a shoe lift, amputation, and limb lengthening.

Delayed amputation should be avoided whenever possible. Ideally, amputation is performed at 10 to 18 months of age when the child is beginning to pull to stand.4 Psychosocial adjustment to amputation and the adjustment to prosthetic wear are rapid at this age.

A common dilemma for parents and consulting physicians is an unwillingness to commit to a path of either multiple lengthenings or early amputation. It is generally agreed, however, that the least effective approach to fibular deficiency is “let’s try lengthening and if it fails, do an amputation.”

The Syme amputation and the Boyd amputation are the two common amputations performed for fibular deficiency.

The Syme amputation is an ankle disarticulation that preserves the heel pad as a weight-bearing surface. This procedure provides better energy efficiency than a transtibial amputation, may be self-suspending, allows weight bearing on the stump without the use of a prosthesis, and is cartilage capped, preventing terminal overgrowth.

The Boyd amputation is a modified ankle disarticulation in which the calcaneus is preserved with the heel pad and fused to the distal tibia.

The best indications for an amputation are a large leg length discrepancy (ie, a difference of more than 30%) at skeletal maturity and a nonfunctional foot.2

The ideal candidate for lengthening has a smaller expected leg length discrepancy (<10%), a stable ankle, and a fully functional foot.

Because both amputation and multiple lengthenings have significant consequences, care must be individualized. This is especially important for patients with leg length discrepancies between 10% and 30%, for which both amputation and lengthening have been shown to be effective with excellent functional outcomes.

ANATOMY

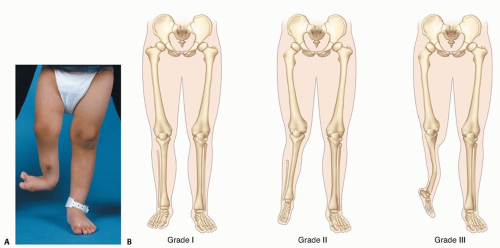

Fibular deficiency is best considered an abnormality that affects the entire limb, not just the fibula (FIG 1A).

The appearance of the leg can vary from nearly normal to severely deformed (FIG 1B).

Potential ipsilateral deformities associated with fibular deficiency are as follows:

Femur: mild femoral shortening, femoral retroversion, lateral femoral hypoplasia

Knee: cruciate ligament deficiency, valgus alignment, patellofemoral instability

Tibia: shortening, anteromedial diaphyseal bowing

Ankle: ankle valgus, absent lateral malleolus, ball-and-socket ankle

Foot: absent tarsal bones, tarsal coalitions, absence of one or more lateral rays

The amount of fibula present does not aid treatment planning. For example, some patients with complete fibular absence have minimal leg length inequality and foot deformity.

An understanding of the anatomy of the ankle and heel is necessary to perform either the Syme or Boyd amputation procedure.

The posterior tibial nerve and artery course posterior to the medial malleolus and split into the medial and lateral plantar nerves. These structures must be protected for the heel pad to maintain its sensation and viability.

PATHOGENESIS

Unlike tibial deficiency, fibular deficiency occurs sporadically with no inheritance pattern.

No genetic defect has been identified, and no common teratogen is linked to fibular deficiency.

Major limb malformations associated with fibular deficiency occur by the seventh week of fetal development.

NATURAL HISTORY

Without surgical intervention, the growth of the abnormal limb remains proportional to the normal side. Therefore, a final leg length discrepancy is predictable.

For example, if the short leg is 85% the length of the long side at age 2 years, the length of the short side at maturity also will be 85% of the estimated length of the long side at maturity.

Tibial bowing is present in most cases of complete absence of the fibula. In some cases, this bowing will improve with age.

Unlike anterolateral bowing of the tibia, bowing associated with fibular deficiency does not increase the risk of fracture or pseudarthrosis.

Knee valgus commonly worsens through childhood. It may require surgical treatment when prosthetic modifications are inadequate to compensate for the deformity.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Classically, the limb is short, with an equinovalgus foot and skin dimpling over the midanterior tibia.

Because presentation varies widely, an examination to assess length, alignment, and function is critical to treatment.

Hip range of motion: A common finding is limited internal rotation (<20 to 60 degrees) indicating femoral retroversion.

Leg length assessment: There should be minimal shortening of the thigh. Otherwise, consider proximal femoral focal deficiency. Small leg length discrepancies can be corrected with a shoe lift or lengthening.

Lachman test: Severe anterior/posterior laxity increases the risk of subluxation during lengthening.

Valgus alignment and stability: Small angulation is accommodated through prosthetic adjustment, but larger angulation requires correction.

Tibial bowing requires prosthetic adjustments or correction.

Ankle alignment and stability: Amputation is preferred over lengthening when severe subluxation or instability exists.

Hindfoot mobility: Suspect tarsal coalition if subtalar motion is reduced.

Ray deficiency (number of missing rays): Amputation is indicated when the foot is nonfunctional.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs of the leg (including the distal femur) should be obtained.

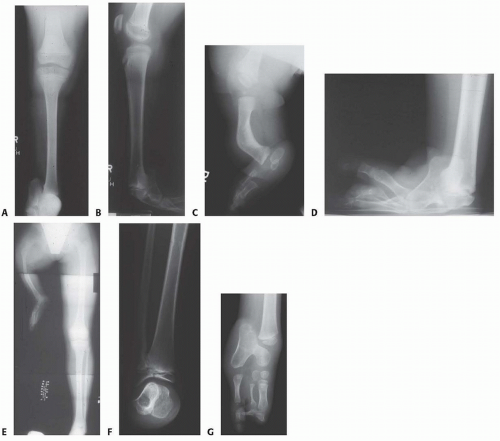

Absence of the anterior cruciate ligament and hypoplasia of the lateral femoral condyle with a valgus joint alignment are common (FIG 2A,B).

The amount of anterior bowing (tibial kyphosis) also can be assessed (FIG 2C).

Additional radiographs of the affected limb (ie, femur, ankle, and foot) are obtained as necessary (FIG 2D).

A full-length standing radiograph from hips to ankles should be obtained to check alignment in those children able to stand (FIG 2E).

A scanogram and bone age should be obtained to determine the expected leg length discrepancy at maturity.

The desired limb length difference at maturity should be at least 3.5 cm to accommodate the height of the prosthetic foot. Epiphysiodesis may be necessary to achieve this and should be planned appropriately.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Proximal femoral focal deficiency

Tibial deficiency

Tibial dysplasia

NONOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

If the leg length discrepancy is small, the ankle is stable, and the foot is plantigrade, a shoe insert or lift may be all that is required.

When amputation or lengthening is needed but must be deferred, an atypical prosthesis that accommodates the foot position can be used.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Syme Amputation

Meticulous care is needed to preserve the posterior tibial nerve and vessels to maintain a sensate stump.

Care should be taken not to leave any cartilage remnants of the calcaneus during resection.

The malleoli should not be resected in children.

The heel pad may be proximal to the ankle joint and can be difficult to bring distally, even after sectioning the Achilles tendon.

The Pirogoff modification maintains a portion of the calcaneus, which is fused to the distal tibia to better fix the heel pad.

Because in young children the distal tibial physis must be resected to obtain fusion of the calcaneus to the tibia, this is really a modification of the Boyd amputation because distal growth of the tibia will be lost.

Advantages

Simple technique

Rapid prosthetic fitting

The stump is shorter and often tapered, which improves cosmesis (but also may inhibit end bearing)

Disadvantages

Heel pad migration (FIG 3)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree