Surviving professional life ethically

Objectives

• Describe what “a caring response” entails when the object of care is you.

• Discuss the place of self respect in your ability to survive professional life ethically.

• Describe what a personal values system is and its relationship to caring for yourself.

• Evaluate your own personal values system.

• Describe the idea of a reflection group and its function in helping to maintain personal integrity.

New terms and ideas you will encounter in this chapter

self care

self respect

personal values system

duties to yourself

aspirations

responsibilities to yourself

exemplar

conscience

conscientious objection

cooperation with wrongdoing

principle of material cooperation

reflection group

Topics in this chapter introduced in earlier chapters

| Topic | Introduced in chapter |

| Personal morality | 1 |

| Integrity | 1 |

| Moral repugnance | 1 |

| A caring response | 2 |

| Responsibility = accountability + responsiveness | 2 |

| Moral distress | 3 |

| Emotions | 3 |

| Ethical dilemma | 3 |

| Intent | 3 |

| Moral agency | 3 |

| Duties | 4 |

| Beneficence | 4 |

| Six-step process | 5 |

Introduction

You have come a long way in thinking about the ethical dimensions of professional practice in a general way, and in Chapter 6, you focused on them in relation to your role as a student. This chapter gives you an opportunity to think about the essential task of self care as you assume your professional role and throughout your professional life. Use of the six-step process for self care issues, many of which have ethics problems embedded in them, will illustrate ways for you to take care of yourself in your professional role. We believe it is extremely important that you honor your deep personal values and needs because as a professional you are always expected to think about others. How can you also take care of yourself in ways that prepare you to flourish in your professional role in all kinds of situations you will encounter? Janice K.’s story helps to focus this discussion.

This story could lead to many interesting and important ethical discussions, but in this chapter, we focus on the prime importance of your personal values and needs as foundational wellsprings of survival in your professional career. Many of your values have a moral component, comprising your personal morality. You have had some opportunities to think about your personal morality already in the course of studying this text. In Chapter 1, you were introduced to the ideas of personal morality and integrity and some ways that society tries to protect these in professionals. In Chapter 6, your integrity was raised again in regard to areas where you must exercise your moral agency as a student. So far, every story in this text has posed an ethical problem to you as you try to put yourself into the shoes of the person who is the moral agent searching for a caring response. Now you have an opportunity to step back and focus on yourself.

In Janice’s situation, her beliefs and the values that inform those beliefs are powerful forces that guide her thinking about her duties and what kind of character traits she should strive to develop so that she can flourish as a human in any situation, including her workplace. That is the challenge each of us faces. The next section turns the lens from your quest for a caring response solely focused on the well-being of the patient to considering what you can to do act in a way that takes good care of yourself too. Is there a way to think about a caring response to yourself that honors your own values and needs, even in your role as a professional? We think yes.

The goal: a caring response

At the center of finding a caring response to yourself is the development of deep self respect. Respect comes from a Latin root that means to hold something or someone in high regard. Respect for the dignity of individuals is an overriding virtue in professional ethics. But respect is almost always understood as referring to the deference one pays to another person, particularly the patient. Where in professional ethics is there encouragement to cultivate and incorporate respect for oneself?

Traditionally, very little about self respect has been found in the professional ethics literature. It has taken an understanding of modern moral psychology to bring it together with respect for others. An American moral philosopher, John Rawls, relied heavily on psychology to help clarify the relationship of respect for self and respect for others.1 As adults, he notes, one source of self respect is the awareness that we are contributing to society’s well-being. Professionals have an opportunity for almost daily feedback about how their contributions to patients’ lives are helping society. This feeds the idea that their own needs also deserve to be respected. And so unlike other analyses that make respect solely a virtue about how to respond to others, Rawls interprets the development of self respect as an engine that can drive our daily activities towards human flourishing. True self respect allows us to flourish as selves and, in turn, allows us to have high regard for the societal tasks we assume to do our part in supporting human flourishing for others as well.

Your understanding of self respect as a wellspring that nourishes your professional obligation to respect others will result in your recognition that a lack of self respect will undermine your ability to enjoy deep job satisfaction.2 A recent study highlights that health professionals who find meaning in their professional activities also have a strong connection with their deep values and moral orientation and strive to live according to them.3 Their self respect partially is tied up with having basic values from which to draw and is reinforced by acting according to those values.

In short, the often overlooked attention to building self respect is an extremely important dimension of exercising a caring response toward yourself.

The six-step process in self care

The six-step process of ethical decision making can be applied to challenges that threaten to pit your care of yourself against other loyalties and duties that you face in your professional role. It sounds contradictory to put yourself ahead of others when Chapter 2 focused so intensely on the focus of your care being with the patient first and foremost. Now we have an opportunity to examine further what happens when and if your personal beliefs, convictions, needs, or limitations counsel you to put yourself first and how to be sure that in these instances you do not unduly compromise your professional responsibility to take the patient’s interests deeply into account.

Step 1: gather relevant information

In all situations that involve questions of decisions about self care in your professional role, a key piece of information is that there are many barriers to acting in your own best interest. You will be faced with ample opportunities to compromise your own care in your professional role. The situation Janice faces presents an ethical challenge regarding how to live out personal values based on her religious convictions in an institutional environment. She believes that to go along with the clinic’s proposed new practice threatens to compromise her spiritual and psychological well-being. Understandably, she is distressed about how to exercise self care. But there are other common types of situations too. For instance, one challenge arises when the workplace is short staffed. Many professionals decide to stay overtime or work on their usual days off to help fill a gap of patient needs that otherwise will go unmet, even though they know that their duties to their families or others are shortchanged. Harder still to justify for many is that they simply need a break from the workplace pressures even though patients and colleagues will suffer. In a previous chapter, you met the young professional who wanted to go to a church supper on Friday evening to socialize with her new rural neighbors and in rushing through her patient care situation felt she had made a serious mistake. Although in this instance we would agree, the problem is that for many young professionals like her this one unfortunate situation may undermine her self-confidence in the basic idea that she does need to make decisions that serve her well personally over the long haul of her demanding workplace responsibilities.

We may seem to be overstressing health professionals’ tendency to compromise self care, but the professional literature supports the seriousness of the tension professionals experience. The stresses sometimes arise out of the culture of the professions themselves. This is illustrated in a study of physical therapists who incurred work-related musculoskeletal disorders. The investigators found that the therapists’ need to continue behaviors they believed best expressed care for the patients, together with their desire to appear knowledgeable and skilled in their ability to remain injury free, sometimes worked against their recovery from injury. These therapists had to leave the profession because of disturbing symptoms associated with their injury, a loss for them, their patients, and the clinical environment of health care.4 A part of the terrible irony of this situation is that the American Physical Therapy Association at that time was a sponsor of Decade, an international, multidisciplinary initiative to improve health-related quality of life for people with musculoskeletal disorders. Members of this and other professions often have been unable to “practice what they preach,” with high prices to pay for it. As health professionals, we must reflect on our own needs and values and begin early in our careers to analyze the influence that they have on our practice.

Information gained from identifying your personal values

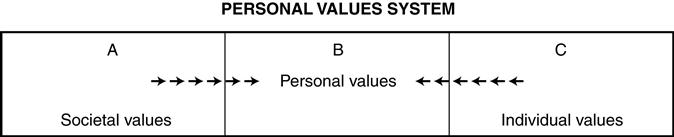

A personal values system is the set of values you have reflected on and chosen that will help you lead a good life. Usually people adopt personal values that partially overlap with societal values and that are in harmony with them.5 Amy Haddad and Ruth Purtilo have represented and explained values in more detail according to the following scheme:

In Figure 7-1, area A represents values developed by society. Many times we accept these values because we want to live peacefully and harmoniously in society. Examples include obedience to traffic laws or other laws, adherence to etiquette, and willingness to pay taxes. Area C represents individual values that are important to you simply because you value them individually. You receive personal benefits from them. Many people cherish time to relax with a good book or pursue a hobby or sport. Having time alone “doing nothing” can be restorative and relaxing. The area of overlap, area B, represents values that you have internalized so that they not only are shared by other people in society but also are perceived as your own values. The motivations for accepting them are that leading a good life includes not only living harmoniously in society but also experiencing personal satisfactions and self-fulfillment. For many, some of these values include friendship, economic independence, and the realization of certain character traits such as fairness or courage. Most people integrate these three into a lifestyle and personal values system, drawing at times on all three areas: A, B, and C. Many values are moral values, and in this case, you can readily discern their relation to the personal, group, and societal moralities presented in Chapter 1.

Reflection

Name some personal values that help to give meaning and enjoyment to your life. Include at least one that you would identify as a moral value, such as honesty or justice.

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

As you study to become a professional, you will also incorporate some professional values into your personal values system. That process has already begun, and it is highly probable that values introduced into your professional preparation will help to make your career choice fitting within the context of your life. In terms of your professional activities, most of them will be moral values. The upshot is that while we are emphasizing self care in this chapter, the integrity that allows you to go forward with clarity and job satisfaction will require that your professional values be taken deeply into account in every decision you make.

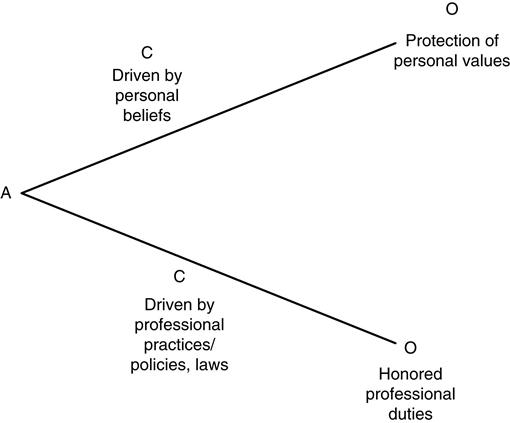

Step 2: identify the type of ethical problem

It is easy to see that Janice is experiencing moral distress. She appears to like the clinic and her job, and until now, she has had no reason to be concerned about its practices or policies. Now her emotional alarm system has gone off, signaling that something is wrong. She is anxious, experiencing sleeplessness, and also feeling vulnerable and angry. We can assume with some certainty that Janice is convinced she is doing harm to herself by participating in a system that allows abortion. From that standpoint, it would make sense for her to withdraw from this institution altogether and apply her skills elsewhere. However, this inclination comes into conflict with some other considerations that constitute an ethical dilemma. She is concerned that if she withdraws completely, she is doing nothing to try to stop this procedure from being offered, thereby, in her words, allowing “both mother and child to be harmed.” And she believes in the services to the socially marginalized population that she can help to provide, knowing that many of her colleagues are reticent to work at this site that they consider to be in a “dangerous” part of town. If she leaves, she believes the clinic will have a hard time finding a qualified replacement for her. Is that serving her personal values better than staying and working from within the system (Figure 7-2)?

In other types of conflicts regarding self care, such as a whether to give up one’s day off because of a short-staffed workplace or to take a much needed “personal mental health” day of rest, the ethical problem may present its own set of considerations. We briefly address each of these in step 3 but focus our attention on Janice’s situation.

Step 3: use ethics theories or approaches to analyze the problem

Janice may gain valuable insight into the course of action that will best help her come to a quiet place in her own conscience by engaging in deep deliberation about any duties she has to herself in this situation.

How is one to interpret the odd phrase, “You owe it to yourself?” Does this mean that you have a duty to be good to yourself? We believe yes.

The duty of self care

In Chapter 2, we included care as a duty in our deliberation about the meaning of a caring response. It is usually interpreted as a duty of caring for others, but it applies equally to oneself. In Chapter 4, duties were placed under the usual umbrella of expectations of moral conduct between individuals. Duties usually describe commitments that individuals make to other people or groups to act in certain ways that are believed to uphold the moral life. Therefore, it is unusual to talk about duties to yourself. One philosopher among others who made a compelling case to do so is W. D. Ross, a 20th century British moral philosopher influential in developing the idea of moral obligation who included the duty of self care and a commitment to improving yourself among his list of duties. He believed that the duty of beneficence (doing good toward others) and doing good toward yourself arise because each of us should produce as much good as possible. Only in honoring the claims on your own health and welfare and in responding to claims from others can a complete picture of the overall good being produced be expressed. In other words, Ross treated self care as a duty in that it brings about good generally, but, of course, you are the major beneficiary!6 His (rule) utilitarian weighing of benefits depended on everyone keeping these duties or rules. We can expect Janice to find a way forward in her dilemma that allows her to honor her duty to be faithful to her religious beliefs while weighing the various alternatives she has open to her. Her moral distress will continue to keep her feelings and emotions alive as she works her way through the challenge she faces.

Reflection

Can you think of some examples in your everyday life when you were not being “good” to yourself, even harming yourself? What are reasons you chose to cheat yourself this way?

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree